Lab 5: Skeletal System II – Appendicular Skeleton and Joints

Appendicular Skeleton, Articulations

When you are prepared for the Test on Week 5 Learning Objectives in Week 6, you will be able to:

- Identify the bones of the appendicular skeleton.

- Identify major morphological features of the appendicular skeleton, which bones they are located in, and their functions (listed in the lab activity).

- Identify the bony features that are the attachment sites for the rotator cuff, hamstrings, and quadriceps.*

- Classify joints structurally (cartilaginous, fibrous, or synovial) and functionally (synarthroses, amphiarthroses, or diarthroses).

- Identify components of a typical synovial joint.

- Identify components of the knee joint.

*W5 will particularly focus on the rotator cuff; the hamstrings and quadriceps attachment sites will be revisited in W7

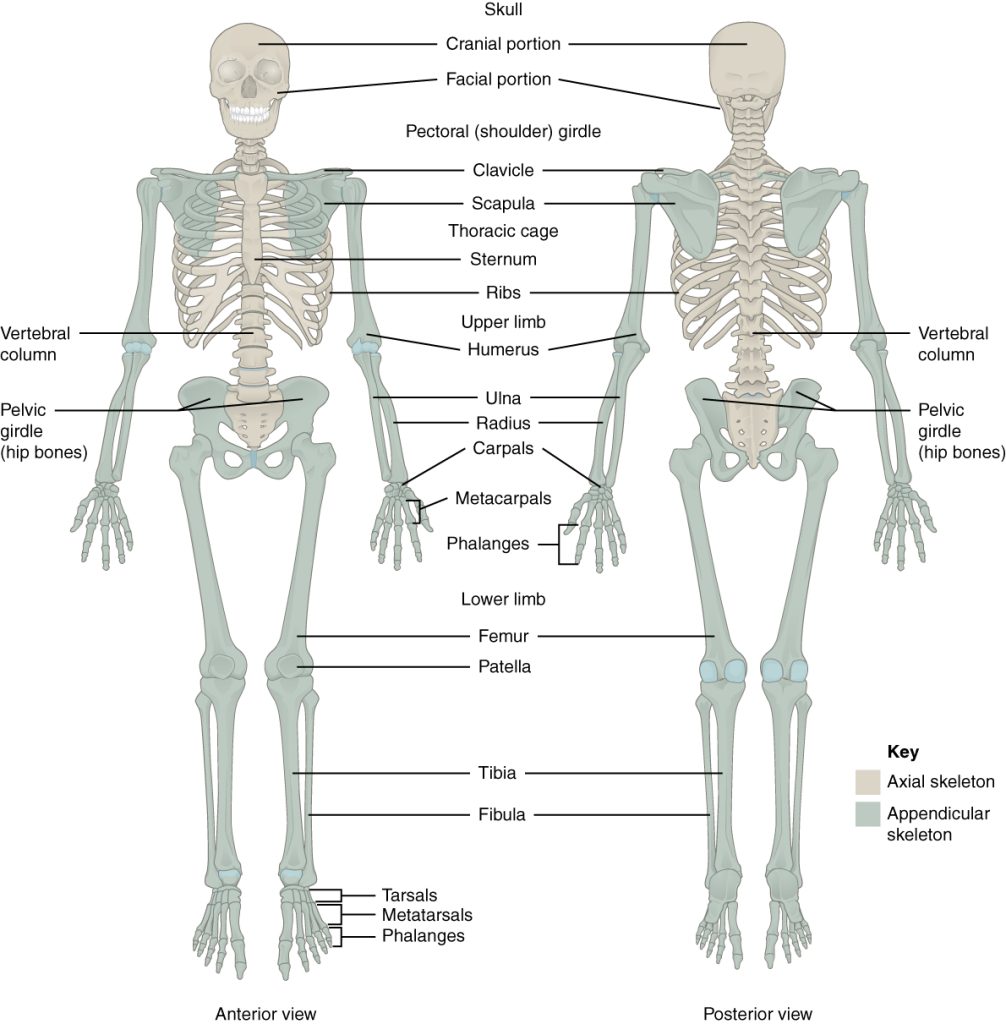

The Appendicular Skeleton

Your skeleton provides the internal supporting structure of the body. The adult axial skeleton consists of 80 bones that form the head and body trunk. Attached to this are the limbs, whose 126 bones constitute the appendicular skeleton (Figure 5.1). These bones are divided into two groups: the bones that are located within the limbs themselves, and the girdle bones that attach the limbs to the axial skeleton. The bones of the shoulder region form the shoulder girdle, which anchors the upper limb to the thoracic cage of the axial skeleton. The lower limb is attached to the vertebral column by the pelvic girdle.

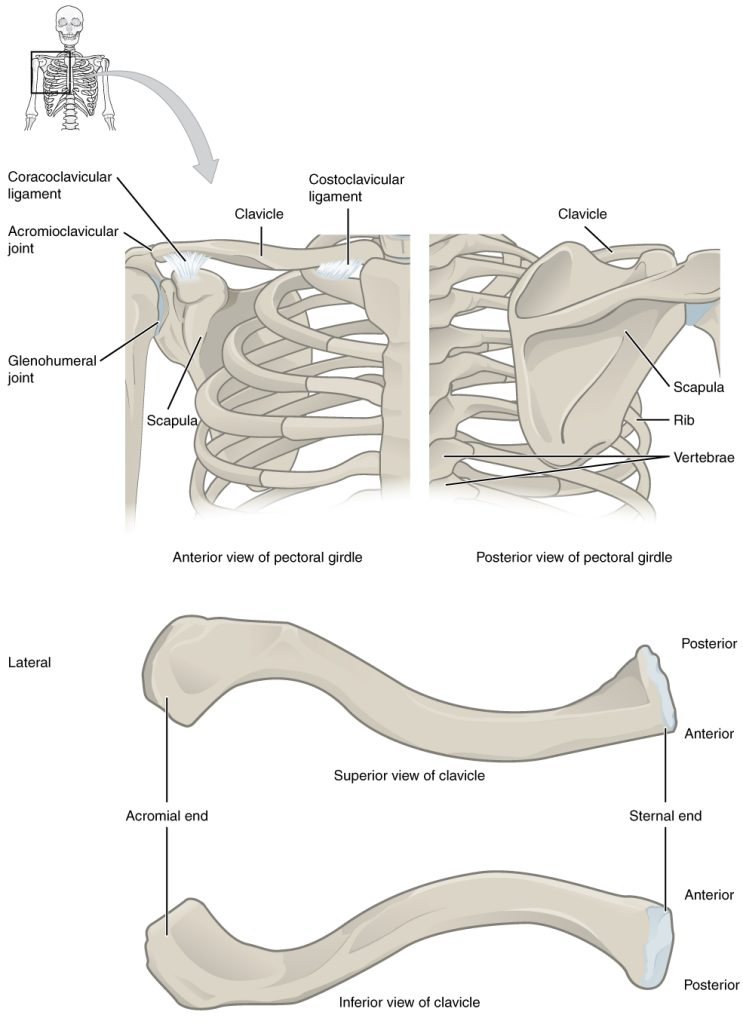

The Shoulder Girdle

The bones that attach each upper limb to the axial skeleton form the shoulder girdle (pectoral girdle). This consists of two bones, the scapula and clavicle (Figure 5.2). The clavicle (collarbone) is an S-shaped bone located on the anterior side of the shoulder. It is attached on its medial end to the sternum of the thoracic cage, which is part of the axial skeleton. The lateral end of the clavicle articulates (joins) with the scapula just above the shoulder joint. You can easily palpate, or feel with your fingers, the entire length of your clavicle.

The scapula (shoulder blade) lies on the posterior aspect of the shoulder. It is supported by the clavicle, which also articulates with the humerus (arm bone) to form the shoulder joint. The scapula is a flat, triangular-shaped bone with a prominent ridge running across its posterior surface. This ridge extends out laterally, where it forms the bony tip of the shoulder and joins with the lateral end of the clavicle. By following along the clavicle, you can palpate out to the bony tip of the shoulder, and from there, you can move back across your posterior shoulder to follow the ridge of the scapula. Move your shoulder around and feel how the clavicle and scapula move together as a unit. Both of these bones serve as important attachment sites for muscles that aid with movements of the shoulder and arm.

The right and left shoulder girdles are not joined to each other, allowing each to operate independently. In addition, the clavicle of each shoulder girdle is anchored to the axial skeleton by a single, highly mobile joint. This allows for the extensive mobility of the entire shoulder girdle, which in turn enhances movements of the shoulder and upper limb.

Clavicle

The clavicle is the only long bone that lies in a horizontal position in the body (Figure 5.2). The clavicle has several important functions. First, anchored by muscles from above, it serves as a strut that extends laterally to support the scapula. This in turn holds the shoulder joint superiorly and laterally from the body trunk, allowing for maximal freedom of motion for the upper limb. The clavicle also transmits forces acting on the upper limb to the sternum and axial skeleton. Finally, it serves to protect the underlying nerves and blood vessels as they pass between the trunk of the body and the upper limb.

The clavicle has three regions: the medial end, the lateral end, and the shaft. The medial end, known as the sternal end of the clavicle, has a triangular shape and articulates with the manubrium portion of the sternum. This forms the sternoclavicular joint, which is the only bony articulation between the shoulder girdle of the upper limb and the axial skeleton. This joint allows considerable mobility, enabling the clavicle and scapula to move in upward/downward and anterior/posterior directions during shoulder movements. The lateral or acromial end of the clavicle articulates with the acromion of the scapula, the portion of the scapula that forms the bony tip of the shoulder.

The clavicle is the most commonly fractured bone in the body. Such breaks often occur because of the force exerted on the clavicle when a person falls onto his or her outstretched arms, or when the lateral shoulder receives a strong blow. Because the sternoclavicular joint is strong and rarely dislocated, excessive force results in the breaking of the clavicle, usually between the middle and lateral portions of the bone. If the fracture is complete, the shoulder and lateral clavicle fragment will drop due to the weight of the upper limb, causing the person to support the sagging limb with their other hand. Muscles acting across the shoulder will also pull the shoulder and lateral clavicle anteriorly and medially, causing the clavicle fragments to override.

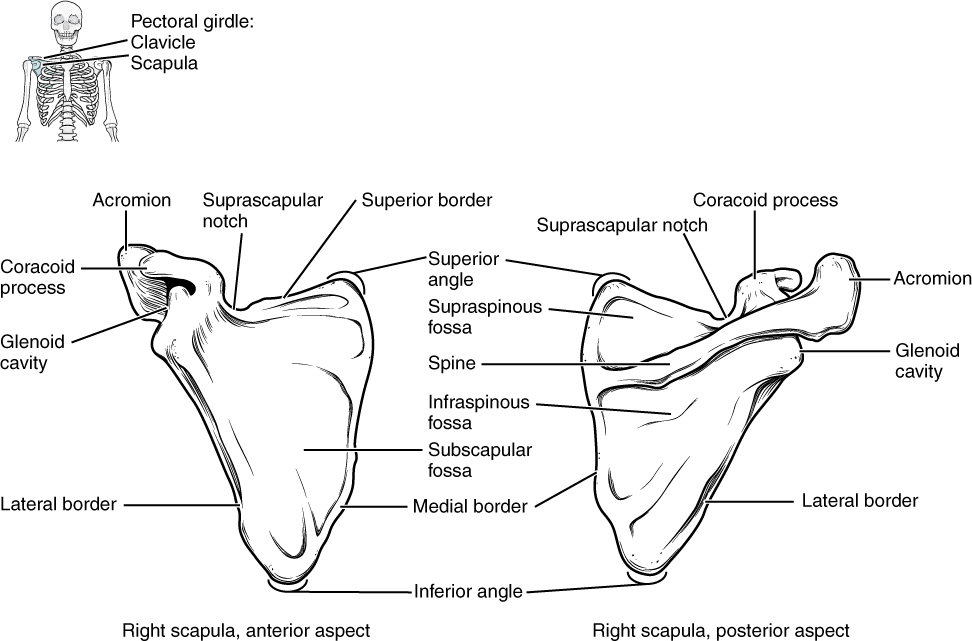

Scapula

The scapula is also part of the shoulder girdle and thus plays an important role in anchoring the upper limb to the body. The scapula is located on the posterior side of the shoulder. It is surrounded by muscles on both its anterior (deep) and posterior (superficial) sides, and thus does not articulate with the ribs of the thoracic cage.

The scapula has several important landmarks (Figure 5.3). The three margins or borders of the scapula, named for their positions within the body, are the superior border of the scapula, the medial border of the scapula, and the lateral border of the scapula. The corners of the triangular scapula, at either end of the medial border, are the superior angle of the scapula, located between the medial and superior borders, and the inferior angle of the scapula, located between the medial and lateral borders. The inferior angle is the most inferior portion of the scapula, and is particularly important because it serves as the attachment point for several powerful muscles involved in shoulder and upper limb movements. The remaining corner of the scapula, between the superior and lateral borders, is the location of the glenoid cavity (glenoid fossa). This shallow depression articulates with the humerus bone of the arm to form the glenohumeral joint (shoulder joint).

The scapula also has two prominent projections. Toward the lateral end of the superior border, between the suprascapular notch and glenoid cavity, is the hook-like coracoid process (coracoid = “shaped like a crow’s beak”), which serves as the attachment site for muscles of the anterior chest and arm. On the posterior aspect, the spine of the scapula is a long and prominent ridge that runs across its upper portion. Extending laterally from the spine is a flattened and expanded region called the acromion or acromial process. The acromion forms the bony tip of the superior shoulder region and articulates with the lateral end of the clavicle, forming the acromioclavicular joint (Figure 5.2). Together, the clavicle, acromion, and spine of the scapula form a V-shaped bony line that provides for the attachment of neck and back muscles that act on the shoulder, as well as muscles that pass across the shoulder joint to act on the arm.

The scapula has three depressions, each of which is called a fossa (plural = fossae). Two of these are found on the posterior scapula, above and below the scapular spine. Superior to the spine is the narrow supraspinous fossa, and inferior to the spine is the broad infraspinous fossa. The anterior (deep) surface of the scapula forms the broad subscapular fossa. All of these fossae provide large surface areas for the attachment of rotator cuff muscles that cross the shoulder joint to act on the humerus.

Bones of the Upper Limb

The upper limb is divided into three regions. These consist of the arm, located between the shoulder and elbow joints; the forearm, which is between the elbow and wrist joints; and the hand, which is located distal to the wrist. There are 30 bones in each upper limb (Figure 5.1). The humerus is the single bone of the upper arm, and the ulna (medially) and the radius (laterally) are the paired bones of the forearm. The base of the hand contains eight bones, each called a carpal bone, and the palm of the hand is formed by five bones, each called a metacarpal bone. The fingers and thumb contain a total of 14 bones, each of which is a phalanx bone of the hand.

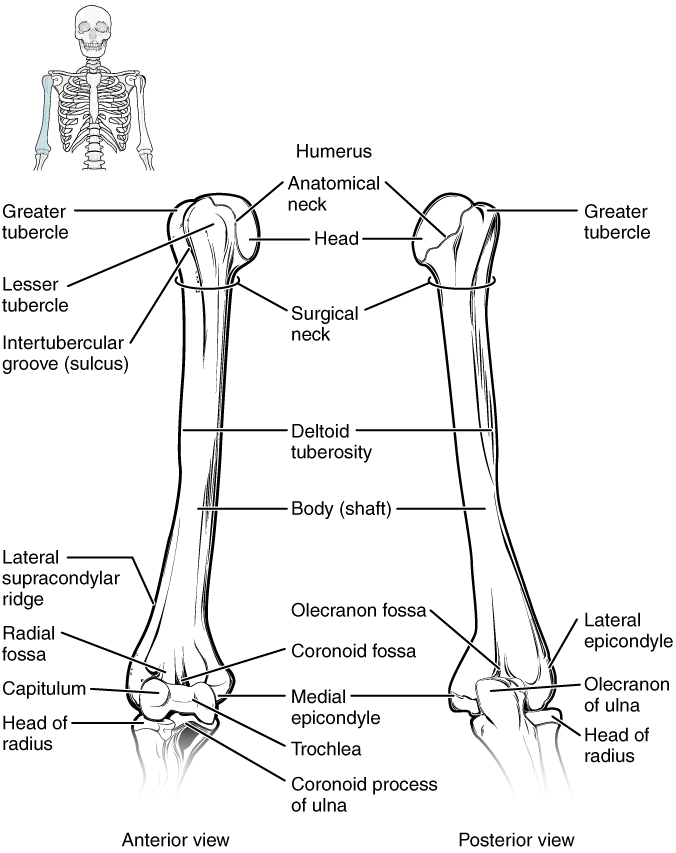

Humerus

The humerus is the single bone of the upper arm region (Figure 5.4). At its proximal end is the head of the humerus. This is the large, round, smooth region that faces medially. The head articulates with the glenoid cavity of the scapula to form the glenohumeral (shoulder) joint. Located on the lateral side of the proximal humerus is an expanded bony area called the greater tubercle. The smaller lesser tubercle of the humerus is found on the anterior aspect of the humerus. Both the greater and lesser tubercles serve as attachment sites for rotator cuff muscles that act across the shoulder joint.

Distally, the humerus becomes flattened. The prominent bony projection on the medial side is the medial epicondyle of the humerus. The much smaller lateral epicondyle of the humerus is found on the lateral side of the distal humerus. These areas are attachment points for muscles that act on the forearm, wrist, and hand. The powerful grasping muscles of the anterior forearm arise from the medial epicondyle, which is thus larger and more robust than the lateral epicondyle that gives rise to the weaker posterior forearm muscles.

The distal end of the humerus has two articulation areas, which join the ulna and radius bones of the forearm to form the elbow joint. The more medial of these areas is the trochlea, a spindle- or pulley-shaped region (trochlea = “pulley”), which articulates with the ulna bone. Immediately lateral to the trochlea is the capitulum (“small head”), a knob-like structure located on the anterior surface of the distal humerus. The capitulum articulates with the radius bone of the forearm. Just above these bony areas are two small depressions. These spaces accommodate the forearm bones when the elbow is fully bent (flexed). Superior to the trochlea is the coronoid fossa, which receives the coronoid process of the ulna, and above the capitulum is the radial fossa, which receives the head of the radius when the elbow is flexed. Similarly, the posterior humerus has the olecranon fossa, a larger depression that receives the olecranon process of the ulna when the forearm is fully extended.

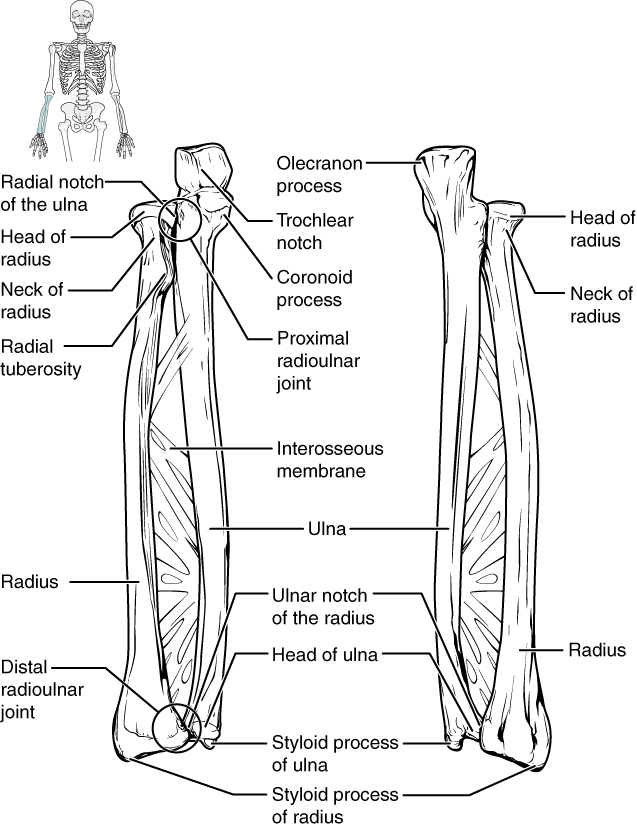

Ulna

The ulna is the medial bone of the forearm. It runs parallel to the radius, which is the lateral bone of the forearm (Figure 5.5). The proximal end of the ulna resembles a crescent wrench with its large, C-shaped trochlear notch. This region articulates with the trochlea of the humerus as part of the elbow joint. The inferior margin of the trochlear notch is formed by a prominent lip of bone called the coronoid process of the ulna. To the lateral side and slightly inferior to the trochlear notch is a small, smooth area called the radial notch of the ulna. This area is the site of articulation between the proximal radius and the ulna, forming the proximal radioulnar joint. The posterior and superior portions of the proximal ulna make up the olecranon process, which forms the bony tip of the elbow.

More distal is the shaft of the ulna. The lateral side of the shaft forms a ridge called the interosseous border of the ulna. This is the line of attachment for the interosseous membrane of the forearm, a sheet of dense connective tissue that unites the ulna and radius bones. The small, rounded area that forms the distal end is the head of the ulna. Projecting from the posterior side of the ulnar head is the styloid process of the ulna, a short bony projection. This serves as an attachment point for a connective tissue structure that unites the distal ends of the ulna and radius.

Radius

The radius runs parallel to the ulna, on the lateral (thumb) side of the forearm (Figure 5.5). The head of the radius is a disc-shaped structure that forms the proximal end. The small depression on the surface of the head articulates with the capitulum of the humerus as part of the elbow joint, whereas the smooth, outer margin of the head articulates with the radial notch of the ulna at the proximal radioulnar joint. The shaft of the radius is slightly curved and has a small ridge along its medial side. This ridge forms the interosseous border of the radius, which, like the similar border of the ulna, is the line of attachment for the interosseous membrane that unites the two forearm bones. The distal end of the radius has a smooth surface for articulation with two carpal bones to form the radiocarpal joint or wrist joint (Figure 5.6). On the medial side of the distal radius is the ulnar notch of the radius. This shallow depression articulates with the head of the ulna, which together form the distal radioulnar joint. The lateral end of the radius has a pointed projection called the styloid process of the radius. This provides attachment for ligaments that support the lateral side of the wrist joint. Compared to the styloid process of the ulna, the styloid process of the radius projects more distally, thereby limiting the range of movement for lateral deviations of the hand at the wrist joint.

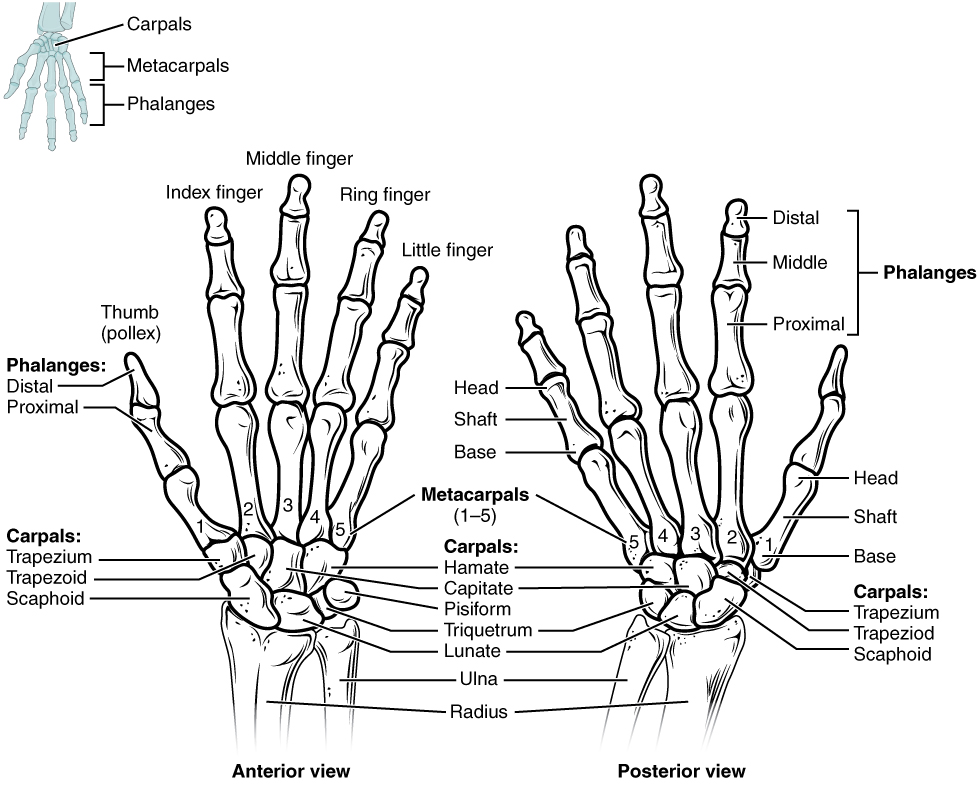

Carpal Bones

The wrist and base of the hand are formed by a series of eight small carpal bones (Figure 5.6). The carpal bones are arranged in two rows, forming a proximal row of four carpal bones and a distal row of four carpal bones. The bones in the proximal row, running from the lateral (thumb) side to the medial side, are the scaphoid (“boat-shaped”), lunate (“moon-shaped”), triquetrum (“three-cornered”), and pisiform (“pea-shaped”) bones. The small, rounded pisiform bone articulates with the anterior surface of the triquetrum bone. The pisiform thus projects anteriorly, where it forms the bony bump that can be felt at the medial base of your hand. The distal bones (lateral to medial) are the trapezium (“table”), trapezoid (“resembles a table”), capitate (“head-shaped”), and hamate (“hooked bone”) bones. The hamate bone is characterized by a prominent bony extension on its anterior side called the hook of the hamate bone.

A helpful mnemonic for remembering the arrangement of the carpal bones is “So Long To Pinky, Here Comes The Thumb.” This mnemonic starts on the lateral side and names the proximal bones from lateral to medial (scaphoid, lunate, triquetrum, pisiform), then makes a U-turn to name the distal bones from medial to lateral (hamate, capitate, trapezoid, trapezium). Thus, it starts and finishes on the lateral side.

In the articulated hand, the carpal bones form a U-shaped grouping. A strong ligament called the flexor retinaculum spans the top of this U-shaped area to maintain this grouping of the carpal bones. The flexor retinaculum is attached laterally to the trapezium and scaphoid bones, and medially to the hamate and pisiform bones. Together, the carpal bones and the flexor retinaculum form a passageway called the carpal tunnel, with the carpal bones forming the walls and floor, and the flexor retinaculum forming the roof of this space. The tendons of nine muscles of the anterior forearm and an important nerve pass through this narrow tunnel to enter the hand. Overuse of the muscle tendons or wrist injury can produce inflammation and swelling within this space. This produces compression of the nerve, resulting in carpal tunnel syndrome, which is characterized by pain or numbness, and muscle weakness in those areas of the hand supplied by this nerve.

Metacarpal Bones

The palm of the hand contains five elongated metacarpal bones. These bones lie between the carpal bones of the wrist and the bones of the fingers and thumb. The proximal end of each metacarpal bone articulates with one of the distal carpal bones (Figure 5.6). The expanded distal end of each metacarpal bone articulates with the proximal phalanx bone of the thumb or one of the fingers. The distal end also forms the knuckles of the hand, at the base of the fingers. The metacarpal bones are numbered 1–5, beginning at the thumb. The first metacarpal bone, at the base of the thumb, is separated from the other metacarpal bones. This allows it a freedom of motion that is independent of the other metacarpal bones, which is very important for thumb mobility. The remaining metacarpal bones are united together to form the palm of the hand.

Phalanx Bones

The fingers and thumb contain 14 bones, each of which is called a phalanx bone (plural = phalanges), named after the ancient Greek phalanx (a rectangular block of soldiers). The thumb (pollex) is digit number 1 and has two phalanges, a proximal phalanx, and a distal phalanx bone. Digits 2 (index finger) through 5 (little finger) have three phalanges each, called the proximal, middle, and distal phalanx bones.

The Pelvic Girdle and Pelvis

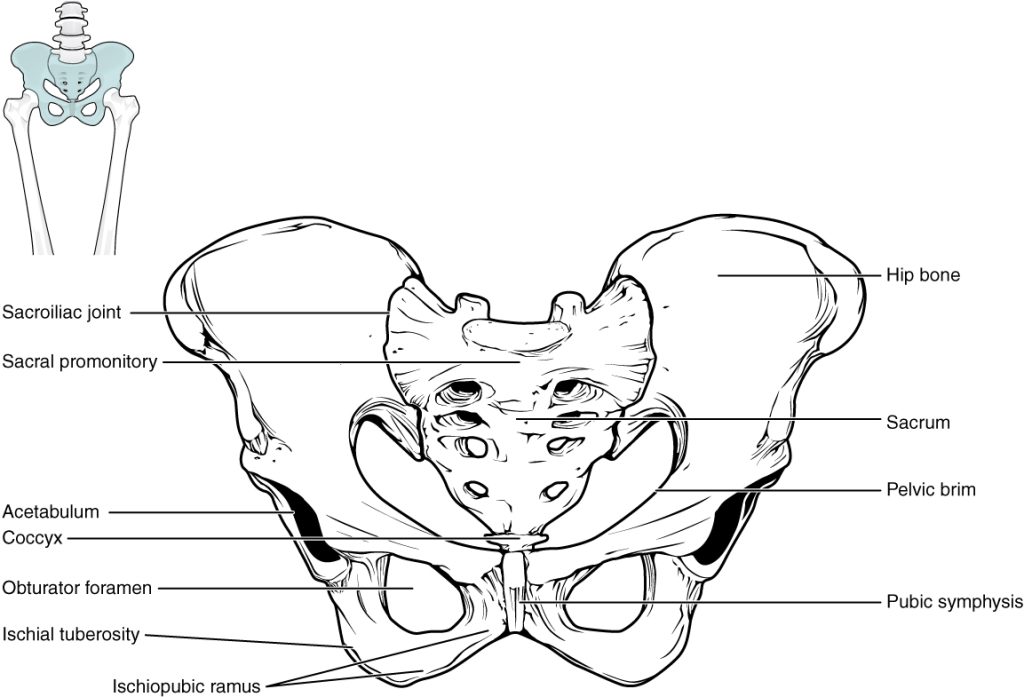

The pelvic girdle (hip girdle) is formed by a single bone, the hip bone or os coxa (coxal = “hip”), which serves as the attachment point for each lower limb. Each hip bone, in turn, is firmly joined to the axial skeleton via its attachment to the sacrum of the vertebral column. The right and left hip bones also converge anteriorly to attach to each other. The bony pelvis is the entire structure formed by the two hip bones, the sacrum, and, attached inferiorly to the sacrum, the coccyx (Figure 5.7).

The pelvis has several important functions. Its primary role is to support the weight of the upper body when sitting and to transfer this weight to the lower limbs when standing. It serves as an attachment point for trunk and lower limb muscles, and also protects the internal pelvic organs. Unlike the bones of the pectoral girdle, which are highly mobile to enhance the range of upper limb movements, the bones of the pelvis are strongly united to each other to form a largely immobile, weight-bearing structure. This is important for stability because it enables the weight of the body to be easily transferred laterally from the vertebral column, through the pelvic girdle and hip joints, and into either lower limb whenever the other limb is not bearing weight. Thus, the immobility of the pelvis provides a strong foundation for the upper body as it rests on top of the mobile lower limbs.

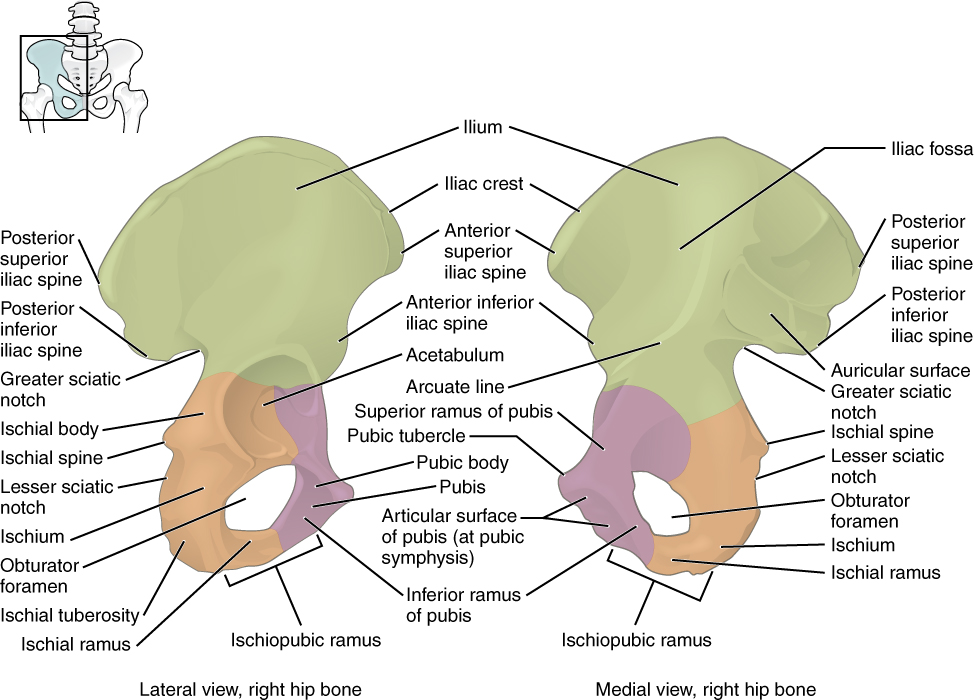

The hip bone, or os coxa, forms the pelvic girdle portion of the pelvis. The paired hip bones are the large, curved bones that form the lateral and anterior aspects of the pelvis. Each adult hip bone is formed by three separate bones that fuse together during the late teenage years. These bony components are the ilium, ischium, and pubis (Figure 5.8). These names are retained and used to define the three regions of the adult hip bone.

The ilium is the fan-like, superior region that forms the largest part of the hip bone. It is firmly united to the sacrum at the largely immobile sacroiliac joint (Figure 5.7). The ischium forms the posteroinferior region of each hip bone. It supports the body when sitting. The pubis forms the anterior portion of the hip bone. The pubis curves medially, where it joins to the pubis of the opposite hip bone at a specialized joint called the pubic symphysis.

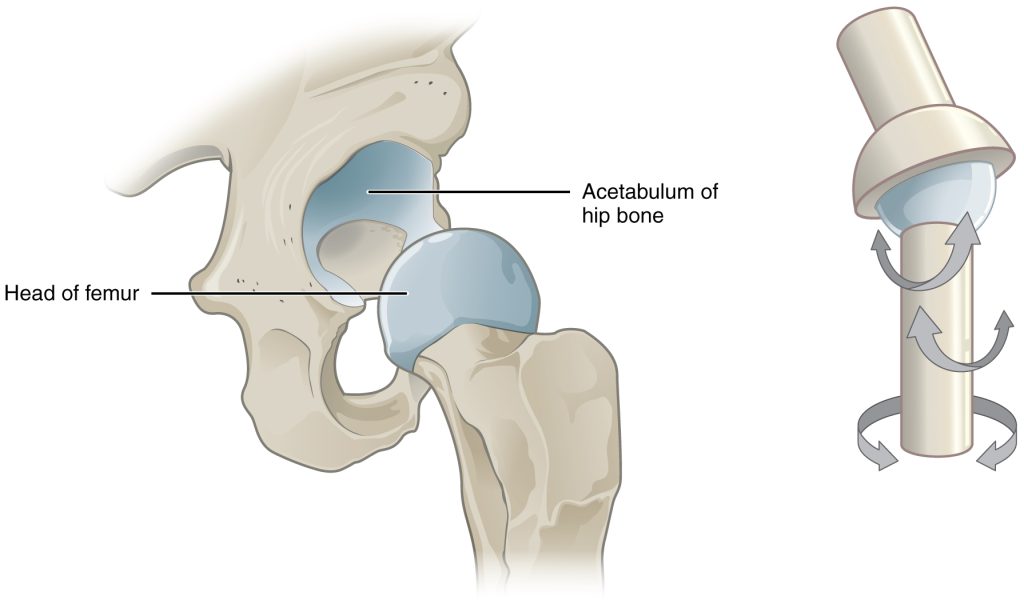

The three areas of each hip bone, the ilium, pubis, and ischium, converge centrally to form a deep, cup-shaped cavity called the acetabulum. This is located on the lateral side of the hip bone and is part of the hip joint. The large opening in the anteroinferior hip bone between the ischium and pubis is the obturator foramen. This space is largely filled in by a layer of connective tissue and serves for the attachment of muscles on both its internal and external surfaces.

Ilium

When you place your hands on your waist, you can feel the arching, superior margin of the ilium along your waistline (Figure 5.8). This curved, superior margin of the ilium is the iliac crest. The rounded, anterior termination of the iliac crest is the anterior superior iliac spine. This important bony landmark can be felt at your anterolateral hip. Inferior to the anterior superior iliac spine is a rounded protuberance called the anterior inferior iliac spine. Both of these iliac spines serve as attachment points for muscles of the thigh. Posteriorly, the iliac crest curves downward to terminate as the posterior superior iliac spine. Muscles and ligaments surround but do not cover this bony landmark, thus sometimes producing a depression seen as a “dimple” located on the lower back. More inferiorly is the posterior inferior iliac spine. This is located at the inferior end of a large, roughened area called the auricular surface of the ilium. The auricular surface articulates with the auricular surface of the sacrum to form the sacroiliac joint. Both the posterior superior and posterior inferior iliac spines serve as attachment points for the muscles and very strong ligaments that support the sacroiliac joint. The large, inverted U-shaped indentation located on the posterior margin of the lower ilium is called the greater sciatic notch.

Ischium

The ischium forms the posterolateral portion of the hip bone (Figure 5.8). The large, roughened area of the inferior ischium is the ischial tuberosity. This serves as the attachment for the posterior thigh muscles and also carries the weight of the body when sitting. You can feel the ischial tuberosity if you wiggle your pelvis against the seat of a chair. Projecting superiorly and anteriorly from the ischial tuberosity is a narrow segment of bone called the ischial ramus. The slightly curved posterior margin of the ischium above the ischial tuberosity is the lesser sciatic notch. The bony projection separating the lesser sciatic notch and greater sciatic notch is the ischial spine.

Pubis

The pubis forms the anterior portion of the hip bone (Figure 5.8). The enlarged medial portion of the pubis is the pubic body. The pubic body is joined to the pubic body of the opposite hip bone by the pubic symphysis. Extending downward and laterally from the body is the inferior pubic ramus. The pubic arch is the bony structure formed by the pubic symphysis, and the bodies and inferior pubic rami of the adjacent pubic bones. The inferior pubic ramus extends downward to join the ischial ramus. Together, these form the single ischiopubic ramus, which extends from the pubic body to the ischial tuberosity. The inverted V-shape formed as the ischiopubic rami from both sides come together at the pubic symphysis is called the subpubic angle.

Bones of the Lower Limb

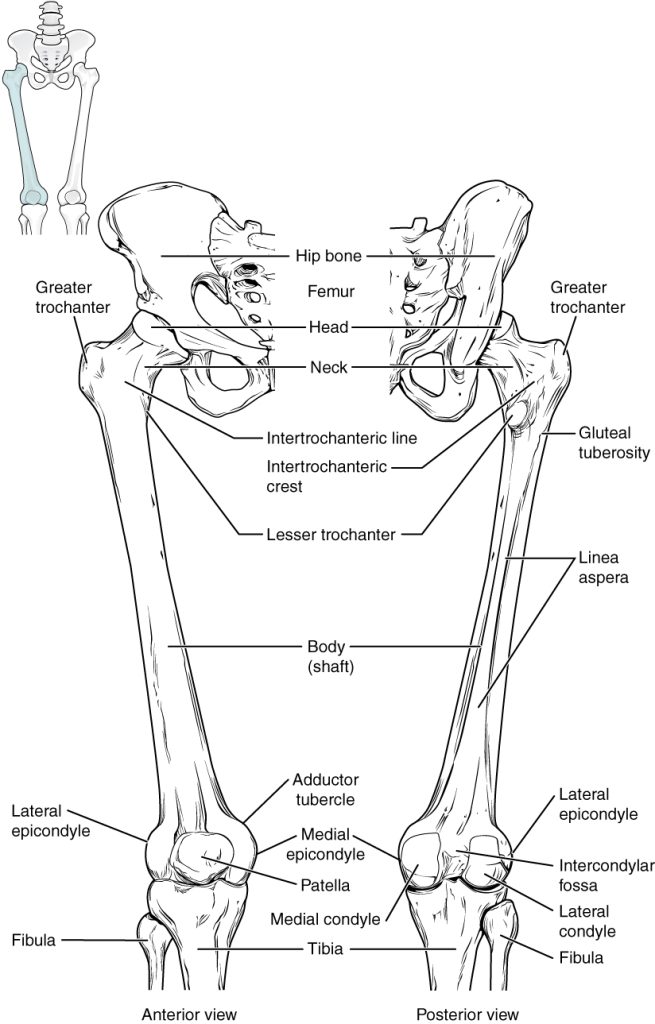

Like the upper limb, the lower limb is divided into three regions. The thigh is that portion of the lower limb located between the hip joint and knee joint. The leg is specifically the region between the knee joint and the ankle joint. Distal to the ankle is the foot. The lower limb contains 30 bones. These are the femur, patella, tibia, fibula, tarsal bones, metatarsal bones, and phalanges (Figure 5.1). The femur is the single bone of the thigh. The patella is the kneecap and articulates with the distal femur. The tibia is the larger, weight-bearing bone located on the medial side of the leg, and the fibula is the thin bone of the lateral leg. The bones of the foot are divided into three groups. The posterior portion of the foot is formed by a group of seven bones, each of which is known as a tarsal bone, whereas the mid-foot contains five elongated bones, each of which is a metatarsal bone. The toes contain 14 small bones, each of which is a phalanx bone of the foot.

Femur

The femur, or thigh bone, is the single bone of the thigh region (Figure 5.9). It is the longest and strongest bone of the body, and accounts for approximately one-quarter of a person’s total height. The rounded, proximal end is the head of the femur, which articulates with the acetabulum of the hip bone to form the hip joint. The narrowed region below the head is the neck of the femur. This is a common area for fractures of the femur. The greater trochanter is the large, upward, bony projection located above the base of the neck. Multiple muscles that act across the hip joint attach to the greater trochanter, which, because of its projection from the femur, gives additional leverage to these muscles. The greater trochanter can be felt just under the skin on the lateral side of your upper thigh. The lesser trochanter is a small, bony prominence that lies on the medial aspect of the femur, just below the neck. A single, powerful muscle attaches to the lesser trochanter.

The elongated shaft of the femur has a slight anterior bowing or curvature. At its proximal end, the posterior shaft has the gluteal tuberosity, a roughened area extending inferiorly from the greater trochanter. More inferiorly, the gluteal tuberosity becomes continuous with the linea aspera (“rough line”). This is the roughened ridge that passes distally along the posterior side of the mid-femur. Multiple muscles of the hip and thigh regions make long, thin attachments to the femur along the linea aspera.

The distal end of the femur has medial and lateral bony expansions. On the lateral side, the smooth portion that covers the distal and posterior aspects of the lateral expansion is the lateral condyle of the femur. The roughened area on the outer, lateral side of the condyle is the lateral epicondyle of the femur. Similarly, the smooth region of the distal and posterior medial femur is the medial condyle of the femur, and the irregular outer, medial side of this is the medial epicondyle of the femur. The lateral and medial condyles articulate with the tibia to form the knee joint. The epicondyles provide attachment for muscles and supporting ligaments of the knee. Anteriorly, the smooth surfaces of the condyles join together to form a wide groove called the patellar surface, which provides for articulation with the patella bone. The combination of the medial and lateral condyles with the patellar surface gives the distal end of the femur a horseshoe (U) shape.

Patella

The patella (kneecap) is the largest sesamoid bone of the body (Figure 5.9). A sesamoid bone is a bone that is incorporated into the tendon of a muscle where that tendon crosses a joint. The sesamoid bone articulates with the underlying bones to prevent damage to the muscle tendon due to rubbing against the bones during movements of the joint. The patella is found in the tendon of the quadriceps femoris muscle, the large muscle of the anterior thigh that passes across the anterior knee to attach to the tibia. The patella articulates with the patellar surface of the femur and thus prevents rubbing of the muscle tendon against the distal femur. The patella also lifts the tendon away from the knee joint, which increases the leverage power of the quadriceps femoris muscle as it acts across the knee. The patella does not articulate with the tibia.

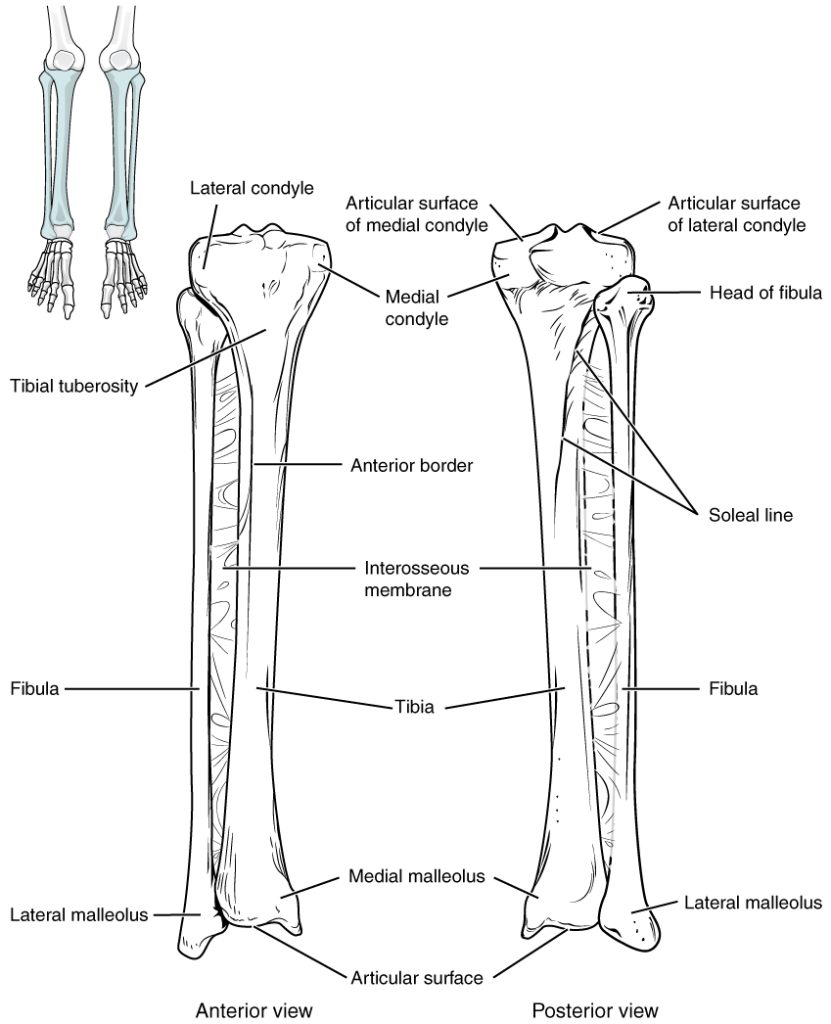

Tibia

The tibia (shin bone) is the medial bone of the leg and is larger than the fibula, with which it is paired (Figure 5.10). The tibia is the main weight-bearing bone of the lower leg and the second longest bone of the body, after the femur. The medial side of the tibia is located immediately under the skin, allowing it to be easily palpated down the entire length of the medial leg.

The proximal end of the tibia is greatly expanded. The two sides of this expansion form the medial condyle of the tibia and the lateral condyle of the tibia. The tibia does not have epicondyles. The top surface of each condyle is smooth and flattened. These areas articulate with the medial and lateral condyles of the femur to form the knee joint. Between the articulating surfaces of the tibial condyles is the intercondylar eminence, an irregular, elevated area that serves as the inferior attachment point for two supporting ligaments of the knee.

The tibial tuberosity is an elevated area on the anterior side of the tibia, near its proximal end. It is the final site of attachment for the muscle tendon associated with the patella. More inferiorly, the shaft of the tibia becomes triangular in shape. A small ridge running down the lateral side of the tibial shaft is the interosseous border of the tibia. This is for the attachment of the interosseous membrane of the leg, the sheet of dense connective tissue that unites the tibia and fibula bones.

The large expansion found on the medial side of the distal tibia is the medial malleolus (“little hammer”). This forms the large bony bump found on the medial side of the ankle region. Both the smooth surface on the inside of the medial malleolus and the smooth area at the distal end of the tibia articulate with the talus bone of the foot as part of the ankle joint. On the lateral side of the distal tibia is a wide groove called the fibular notch. This area articulates with the distal end of the fibula, forming the distal tibiofibular joint.

Fibula

The fibula is the slender bone located on the lateral side of the leg (Figure 5.10). The fibula does not bear weight. It serves primarily for muscle attachments and thus is largely surrounded by muscles. Only the proximal and distal ends of the fibula can be palpated.

The head of the fibula is the small, knob-like, proximal end of the fibula. It articulates with the inferior aspect of the lateral tibial condyle, forming the proximal tibiofibular joint. The thin shaft of the fibula has the interosseous border of the fibula, a narrow ridge running down its medial side for the attachment of the interosseous membrane that spans the fibula and tibia. The distal end of the fibula forms the lateral malleolus, which forms the easily palpated bony bump on the lateral side of the ankle. The deep (medial) side of the lateral malleolus articulates with the talus bone of the foot as part of the ankle joint. The distal fibula also articulates with the fibular notch of the tibia.

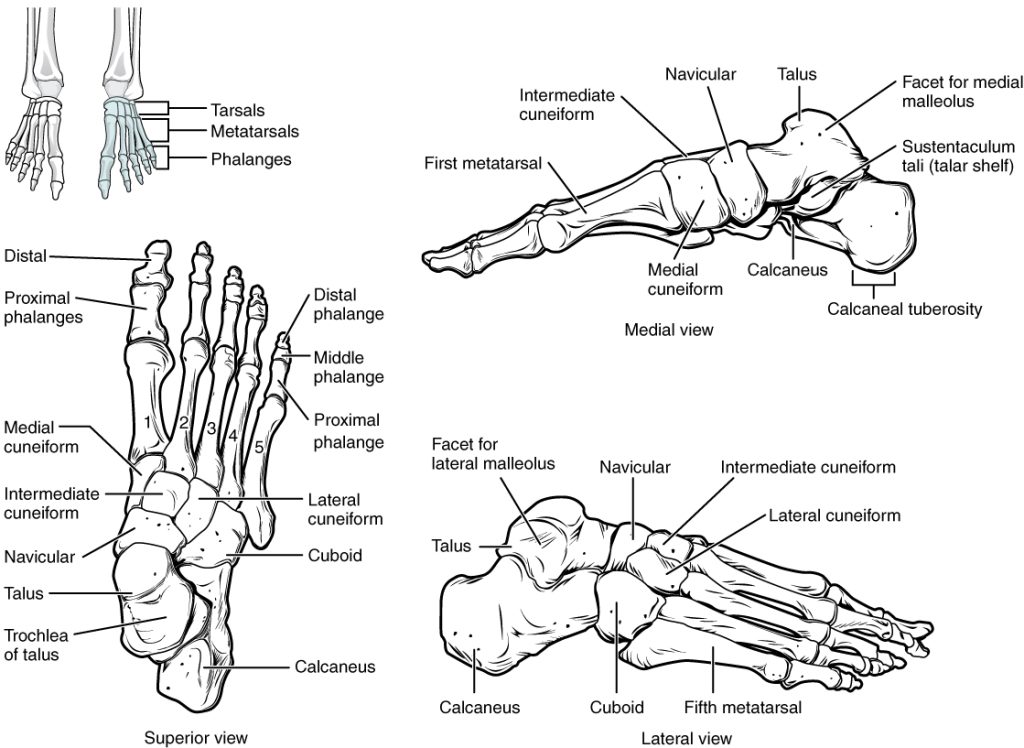

Tarsal Bones

The posterior half of the foot is formed by seven tarsal bones (Figure 5.11). The most superior bone is the talus. This has a relatively square-shaped, upper surface that articulates with the tibia and fibula to form the ankle joint. Three areas of articulation form the ankle joint: The superomedial surface of the talus bone articulates with the medial malleolus of the tibia, the top of the talus articulates with the distal end of the tibia, and the lateral side of the talus articulates with the lateral malleolus of the fibula. Inferiorly, the talus articulates with the calcaneus (heel bone), the largest bone of the foot, which forms the heel. Body weight is transferred from the tibia to the talus to the calcaneus, which rests on the ground.

The cuboid bone articulates with the anterior end of the calcaneus bone. The talus bone articulates anteriorly with the navicular bone, which in turn articulates anteriorly with the three cuneiform (“wedge-shaped”) bones. These bones are the medial cuneiform, the intermediate cuneiform, and the lateral cuneiform. Each of these bones has a broad superior surface and a narrow inferior surface, which together produce the transverse (medial-lateral) curvature of the foot. The navicular and lateral cuneiform bones also articulate with the medial side of the cuboid bone.

Metatarsal Bones

The anterior half of the foot is formed by the five metatarsal bones, which are located between the tarsal bones of the posterior foot and the phalanges of the toes (Figure 5.11). These elongated bones are numbered 1–5, starting with the medial side of the foot. The first metatarsal bone is shorter and thicker than the others. The second metatarsal is the longest. The base of the metatarsal bone is the proximal end of each metatarsal bone. These articulate with the cuboid or cuneiform bones. The expanded distal end of each metatarsal is the head of the metatarsal bone. Each metatarsal bone articulates with the proximal phalanx of a toe to form a metatarsophalangeal joint. The heads of the metatarsal bones also rest on the ground and form the ball (anterior end) of the foot.

Phalanges

The toes contain a total of 14 phalanx bones (phalanges), arranged in a similar manner as the phalanges of the fingers (Figure 5.11). The toes are numbered 1–5, starting with the big toe (hallux). The big toe has two phalanx bones, the proximal and distal phalanges. The remaining toes all have proximal, middle, and distal phalanges.

Joints

Classification of Joints

A joint, also called an articulation, is any place where adjacent bones or bone and cartilage come together (articulate with each other) to form a connection. Joints are classified both structurally and functionally. Structural classifications of joints take into account whether the adjacent bones are strongly anchored to each other by fibrous connective tissue or cartilage, or whether the adjacent bones articulate with each other within a fluid-filled space called a joint cavity. Functional classifications describe the degree of movement available between the bones, ranging from immobile, to slightly mobile, to freely moveable joints. The amount of movement available at a particular joint of the body is related to the functional requirements for that joint. Thus immobile or slightly moveable joints serve to protect internal organs, give stability to the body, and allow for limited body movement. In contrast, freely moveable joints allow for much more extensive movements of the body and limbs.

Functional Classification of Joints

The functional classification of joints is determined by the amount of mobility found between the adjacent bones. Joints are thus functionally classified as a synarthrosis or immobile joint, an amphiarthrosis or slightly moveable joint, or as a diarthrosis, which is a freely moveable joint (arthroun = “to fasten by a joint”).

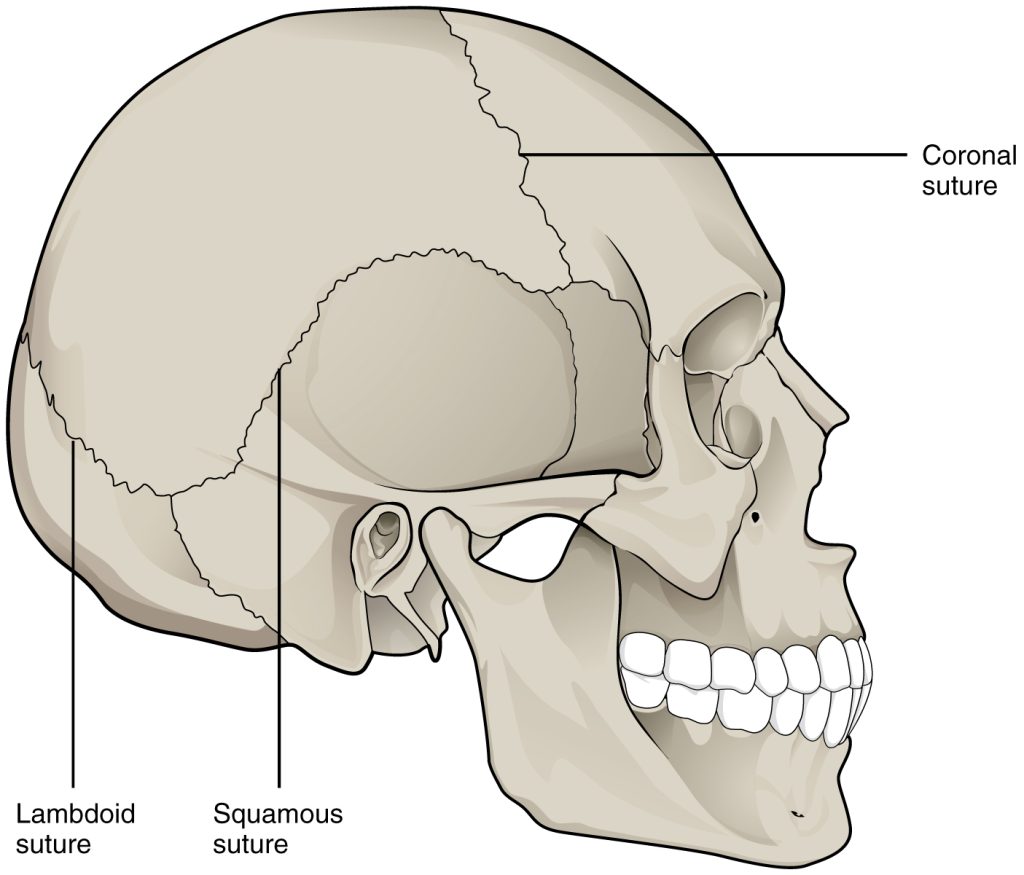

Synarthrosis

An immobile or nearly immobile joint is called a synarthrosis. The immobile nature of these joints provide for a strong union between the articulating bones. This is important at locations where the bones provide protection for internal organs. Examples include sutures, the fibrous joints between the bones of the skull that surround and protect the brain (Figure 5.12), and the manubriosternal joint, the cartilaginous joint that unites the manubrium and body of the sternum for protection of the heart.

Amphiarthrosis

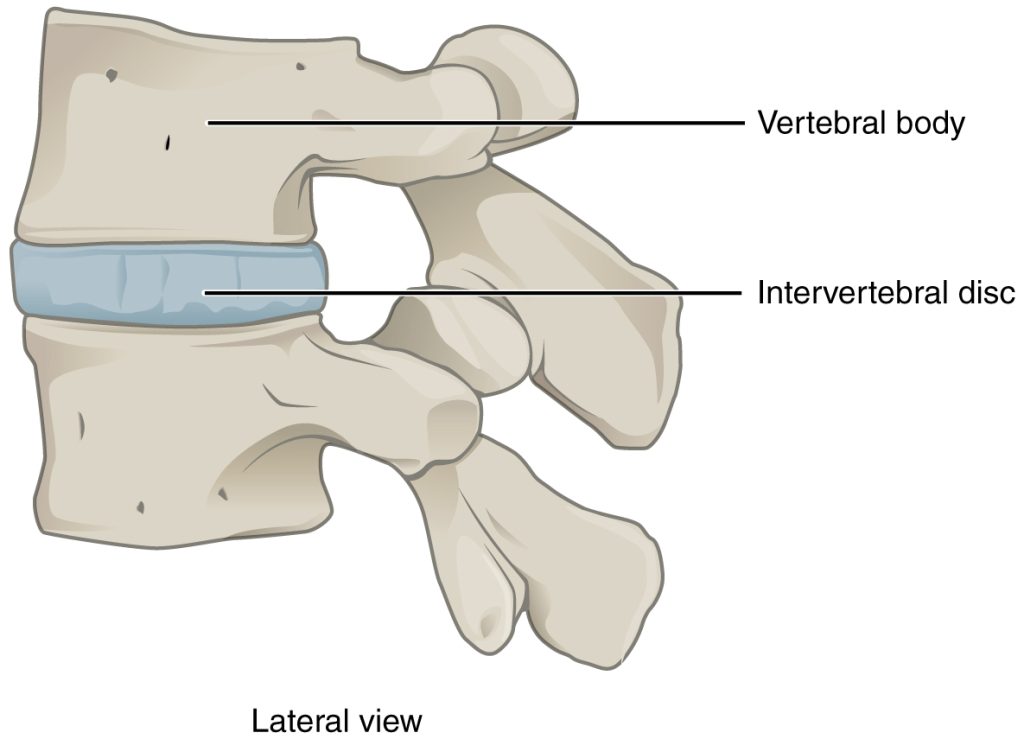

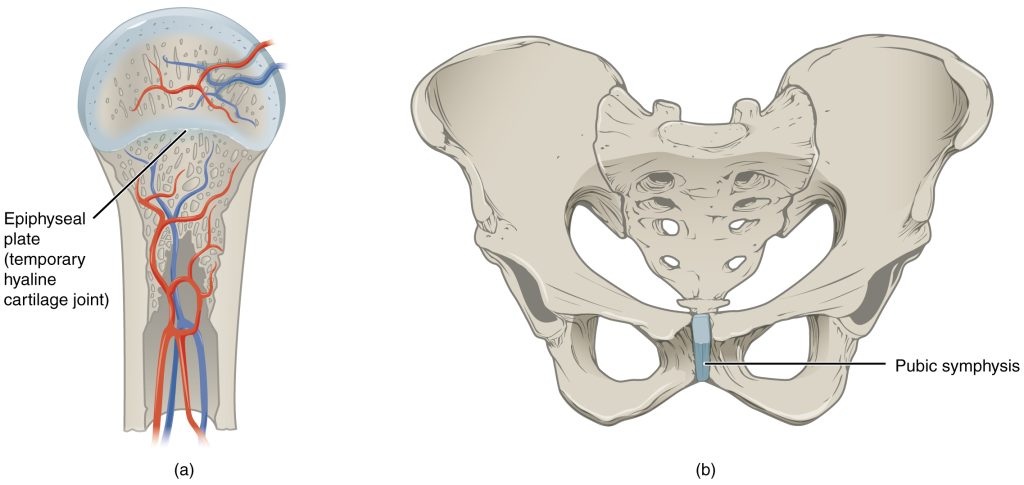

An amphiarthrosis is a joint that has limited mobility. An example of this type of joint is the cartilaginous joint that unites the bodies of adjacent vertebrae. Filling the gap between the vertebrae is a thick pad of fibrocartilage called an intervertebral disc (Figure 5.13). Each intervertebral disc strongly unites the vertebrae but still allows for a limited amount of movement between them. However, the small movements available between adjacent vertebrae can sum together along the length of the vertebral column to provide for large ranges of body movements. Another example of an amphiarthrosis is the pubic symphysis of the pelvis. This is a cartilaginous joint in which the pubic regions of the right and left hip bones are strongly anchored to each other by fibrocartilage. This joint normally has very little mobility. The strength of the pubic symphysis is important in conferring weight-bearing stability to the pelvis.

Diarthrosis

A freely mobile joint is classified as a diarthrosis. These types of joints include all synovial joints of the body, which provide the majority of body movements. Most diarthrotic joints are found in the appendicular skeleton and thus give the limbs a wide range of motion. These joints are divided into three categories, based on the number of axes of motion provided by each. An axis in anatomy is described as the movements in reference to the three anatomical planes: transverse, frontal, and sagittal. Thus, diarthroses are classified as uniaxial (for movement in one plane), biaxial (for movement in two planes), or multiaxial joints (for movement in all three anatomical planes) (Figure 5.14).

Structural Classification of Joints

The structural classification of joints is based on whether the articulating surfaces of the adjacent bones are directly connected by fibrous connective tissue or cartilage, or whether the articulating surfaces contact each other within a fluid-filled joint cavity. These differences serve to divide the joints of the body into three structural classifications. A fibrous joint is where the adjacent bones are united by fibrous connective tissue. At a cartilaginous joint, the bones are joined by hyaline cartilage or fibrocartilage. At a synovial joint, the articulating surfaces of the bones are not directly connected, but instead come into contact with each other within a joint cavity that is filled with a lubricating fluid. Synovial joints allow for free movement between the bones and are the most common joints of the body.

Depending on their location, fibrous joints may be functionally classified as a synarthrosis (immobile joint) or an amphiarthrosis (slightly mobile joint). Cartilaginous joints are also functionally classified as either a synarthrosis or an amphiarthrosis joint. All synovial joints are functionally classified as a diarthrosis joint.

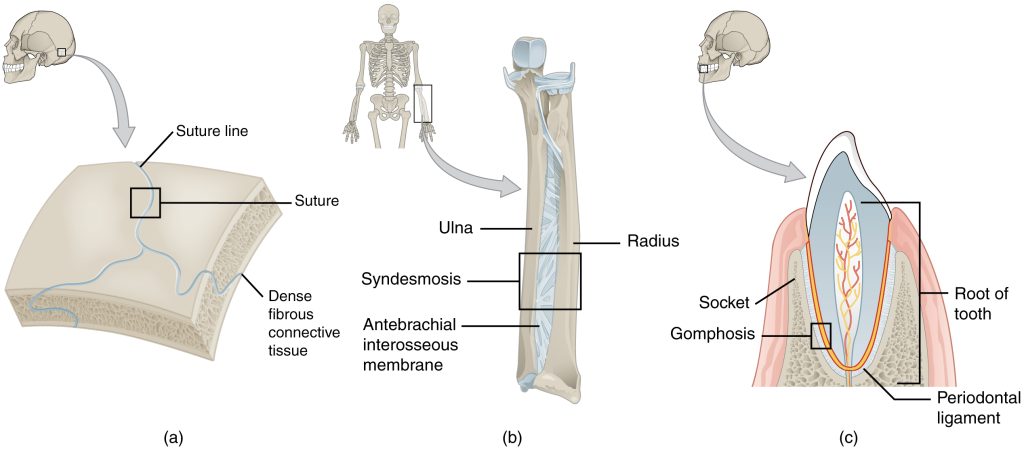

Fibrous Joints

At a fibrous joint, the adjacent bones are directly connected to each other by fibrous connective tissue, and thus the bones do not have a joint cavity between them (Figure 5.15). The gap between the bones may be narrow or wide. There are three types of fibrous joints. A suture is the narrow fibrous joint found between most bones of the skull. At a syndesmosis joint, the bones are more widely separated but are held together by a narrow band of fibrous connective tissue called a ligament or a wide sheet of connective tissue called an interosseous membrane. This type of fibrous joint is found between the shaft regions of the long bones in the forearm and in the leg. Lastly, a gomphosis is the narrow fibrous joint between the roots of a tooth and the bony socket in the jaw into which the tooth fits.

Cartilaginous Joints

As the name indicates, at a cartilaginous joint, the adjacent bones are united by cartilage, a tough but flexible type of connective tissue. These types of joints lack a joint cavity and involve bones that are joined together by either hyaline cartilage or fibrocartilage (Figure 5.16). There are two types of cartilaginous joints. A synchondrosis is a cartilaginous joint where the bones are joined by hyaline cartilage. Also classified as a synchondrosis are places where bone is united to a cartilage structure, such as between the anterior end of a rib and the costal cartilage of the thoracic cage. The second type of cartilaginous joint is a symphysis, where the bones are joined by fibrocartilage.

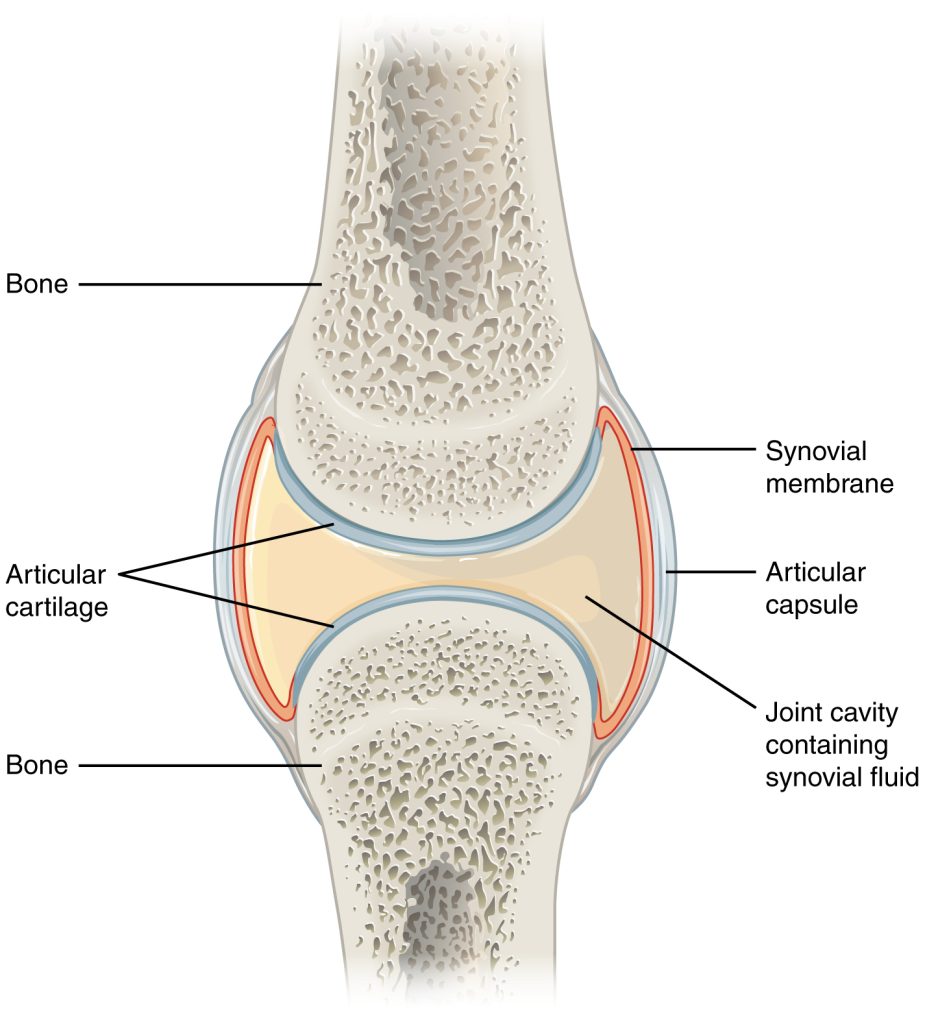

Synovial Joints

Synovial joints are the most common type of joint in the body. A key structural characteristic for a synovial joint that is not seen at fibrous or cartilaginous joints is the presence of a joint cavity (Figure 5.17). This fluid-filled space is the site at which the articulating surfaces of the bones contact each other. Also unlike fibrous or cartilaginous joints, the articulating bone surfaces at a synovial joint are not directly connected to each other with fibrous connective tissue or cartilage. This gives the bones of a synovial joint the ability to move smoothly against each other, allowing for increased joint mobility.

Synovial joints are characterized by the presence of a joint cavity. The walls of this space are formed by the articular capsule, a fibrous connective tissue structure that is attached to each bone just outside the area of the bone’s articulating surface. The bones of the joint articulate with each other within the joint cavity.

Friction between the bones at a synovial joint is prevented by the presence of the articular cartilage, a thin layer of hyaline cartilage that covers the entire articulating surface of each bone. However, unlike at a cartilaginous joint, the articular cartilages of each bone are not continuous with each other. Instead, the articular cartilage acts like a Teflon® coating over the bone surface, allowing the articulating bones to move smoothly against each other without damaging the underlying bone tissue. Lining the inner surface of the articular capsule is a thin synovial membrane. The cells of this membrane secrete synovial fluid (synovia = “a thick fluid”), a thick, slimy fluid that provides lubrication to further reduce friction between the bones of the joint. This fluid also provides nourishment to the articular cartilage, which does not contain blood vessels. The ability of the bones to move smoothly against each other within the joint cavity, and the freedom of joint movement this provides, means that each synovial joint is functionally classified as a diarthrosis.

Outside of their articulating surfaces, the bones are connected together by ligaments, which are strong bands of fibrous connective tissue. These strengthen and support the joint by anchoring the bones together and preventing their separation. Ligaments allow for normal movements at a joint, but limit the range of these motions, thus preventing excessive or abnormal joint movements. At many synovial joints, additional support is provided by the muscles and their tendons that act across the joint. A tendon is the dense connective tissue structure that attaches a muscle to bone. As forces acting on a joint increase, the body will automatically increase the overall strength of contraction of the muscles crossing that joint, thus allowing the muscle and its tendon to serve as a “dynamic ligament” to resist forces and support the joint. This type of indirect support by muscles is very important at the shoulder joint, for example, where the ligaments are relatively weak.

Classification of Synovial Joints

Synovial joints are subdivided based on the shapes of the articulating surfaces of the bones that form each joint. The six types of synovial joints are pivot, hinge, condyloid, saddle, plane, and ball-and socket-joints (Figure 5.18). Each synovial joint of the body is specialized to perform certain movements. The movements that are allowed are determined by the structural classification for each joint. For example, a multiaxial ball-and-socket joint has much more mobility than a uniaxial hinge joint. However, the ligaments and muscles that support a joint may place restrictions on the total range of motion available. Thus, the ball-and-socket joint of the shoulder has little in the way of ligament support, which gives the shoulder a very large range of motion. In contrast, movements at the hip joint are restricted by strong ligaments, which reduce its range of motion but confer stability during standing and weight bearing.

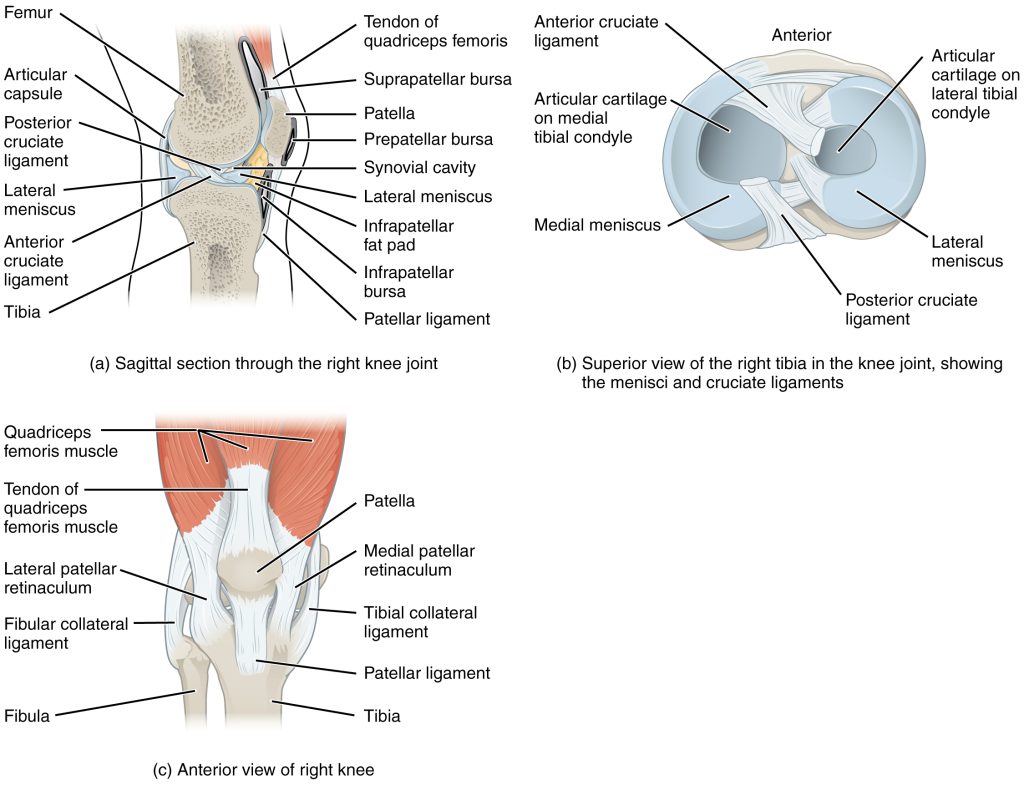

Synovial joint example: The Knee Joint

The knee joint is the largest joint of the body (Figure 5.19). It actually consists of three articulations. The femoropatellar joint is found between the patella and the distal femur. The medial tibiofemoral joint and lateral tibiofemoral joint are located between the medial and lateral condyles of the femur and the medial and lateral condyles of the tibia. All of these articulations are enclosed within a single articular capsule. The knee functions as a hinge joint, allowing flexion and extension of the leg. In addition, some rotation of the leg is available when the knee is flexed, but not when extended. The knee is well constructed for weight bearing in its extended position, but is vulnerable to injuries associated with hyperextension, twisting, or blows to the medial or lateral side of the joint, particularly while weight bearing.

At the femoropatellar joint, the patella slides vertically within a groove on the distal femur. Continuing from the patella to the anterior tibia just below the knee is the patellar ligament. Acting via the patella and patellar ligament, the quadriceps femoris is a powerful muscle that acts to extend the leg at the knee. It also serves as a “dynamic ligament” to provide very important support and stabilization for the knee joint.

The medial and lateral tibiofemoral joints are the articulations between the rounded condyles of the femur and the relatively flat condyles of the tibia. During flexion and extension motions, the condyles of the femur both roll and glide over the surfaces of the tibia. The rolling action produces flexion or extension, while the gliding action serves to maintain the femoral condyles centered over the tibial condyles, thus ensuring maximal bony, weight-bearing support for the femur in all knee positions. As the knee comes into full extension, the femur undergoes a slight medial rotation in relation to tibia. The rotation results because the lateral condyle of the femur is slightly smaller than the medial condyle. Thus, the lateral condyle finishes its rolling motion first, followed by the medial condyle. The resulting small medial rotation of the femur serves to “lock” the knee into its fully extended and most stable position. Flexion of the knee is initiated by a slight lateral rotation of the femur on the tibia, which “unlocks” the knee.

Located between the articulating surfaces of the femur and tibia are two articular discs, the medial meniscus and lateral meniscus (Figure 5.19b). Each is a C-shaped fibrocartilage structure that is thin along its inside margin and thick along the outer margin. They are attached to their tibial condyles, but do not attach to the femur. While both menisci are free to move during knee motions, the medial meniscus shows less movement because it is anchored at its outer margin to the articular capsule and tibial collateral ligament. The menisci provide padding between the bones and help to fill the gap between the round femoral condyles and flattened tibial condyles. Some areas of each meniscus lack an arterial blood supply and thus these areas heal poorly if damaged.

The knee joint has multiple ligaments that provide support, particularly in the extended position (Figure 5.19c). Outside of the articular capsule, located at the sides of the knee, are two extrinsic ligaments. The fibular collateral ligament (lateral collateral ligament) is on the lateral side and spans from the lateral epicondyle of the femur to the head of the fibula. The tibial collateral ligament (medial collateral ligament) of the medial knee runs from the medial epicondyle of the femur to the medial tibia. As it crosses the knee, the tibial collateral ligament is firmly attached on its deep side to the articular capsule and to the medial meniscus, an important factor when considering knee injuries. In the fully extended knee position, both collateral ligaments are taut (tight), thus serving to stabilize and support the extended knee and preventing side-to-side or rotational motions between the femur and tibia.

Inside the knee are two intracapsular ligaments, the anterior cruciate ligament and posterior cruciate ligament. These ligaments are anchored inferiorly to the tibia at the intercondylar eminence, the roughened area between the tibial condyles. The cruciate ligaments are named for whether they are attached anteriorly or posteriorly to this tibial region. Each ligament runs diagonally upward to attach to the inner aspect of a femoral condyle. The cruciate ligaments are named for the X-shape formed as they pass each other (cruciate means “cross”). The posterior cruciate ligament is the stronger ligament. It serves to support the knee when it is flexed and weight bearing, as when walking downhill. In this position, the posterior cruciate ligament prevents the femur from sliding anteriorly off the top of the tibia. The anterior cruciate ligament becomes tight when the knee is extended, and thus resists hyperextension.

Unless otherwise indicated, this chapter contains material adapted from Anatomy and Physiology (on OpenStax), by Betts, et al. and is used under a a CC BY 4.0 international license. Download and access OpenStax Anatomy and Physiology for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction.