Lab 9: Nervous system II – Special Senses

Special senses

Learning Objectives

When you are prepared for the Test on Week 9 Learning Objectives in Week 10, you will be able to:

- Identify structures of the eye and their functions.

- Identify layers of the retina.

- Identify the extrinsic eye muscles, their actions, and innervations.

- Identify structures of the ear and their functions.

- Identify structures of the cochlea.

Senses

A major role of sensory receptors is to help us learn about the environment around us, or about the state of our internal environment. Stimuli from varying sources, and of different types, are received and changed into the electrochemical signals of the nervous system. This occurs when a stimulus changes the cell membrane potential of a sensory neuron. The stimulus causes the sensory cell to produce an action potential that is relayed into the central nervous system (CNS), where it is integrated with other sensory information—or sometimes higher cognitive functions—to become a conscious perception of that stimulus. The central integration may then lead to a motor response.

Describing sensory function with the term sensation or perception is a deliberate distinction. Sensation is the activation of sensory receptor cells at the level of the stimulus. Perception is the central processing of sensory stimuli into a meaningful pattern. Perception is dependent on sensation, but not all sensations are perceived. Receptors are the cells or structures that detect sensations.

Sensory Receptors

Stimuli in the environment activate specialized receptor cells in the peripheral nervous system. Different types of stimuli are sensed by different types of receptor cells. One way to categorize sensory receptors is through a functional classification: which type of stimulus the receptor can detect and how it transduces the stimulus into a nervous signal.

Chemoreceptors can detect ions and macromolecules (chemicals), which leads to an interpretation of taste or smell. Nociceptors detect chemicals from tissue damage or other intense stimuli, which leads to an interpretation of pain. Physical stimuli, such as pressure and vibration, as well as the sensation of sound and body position (balance), are interpreted through a mechanoreceptor. Another physical stimulus that has its own type of receptor is temperature, which is sensed through a thermoreceptor that is either sensitive to temperatures above (heat) or below (cold) normal body temperature. Other stimuli include the electromagnetic radiation from visible light and are detected by photoreceptors. For humans, the only electromagnetic energy that is perceived by our eyes is visible light. Some other organisms have receptors that humans lack, such as the heat sensors of snakes, the ultraviolet light sensors of bees, or magnetic receptors in migratory birds.

Gustation (taste)

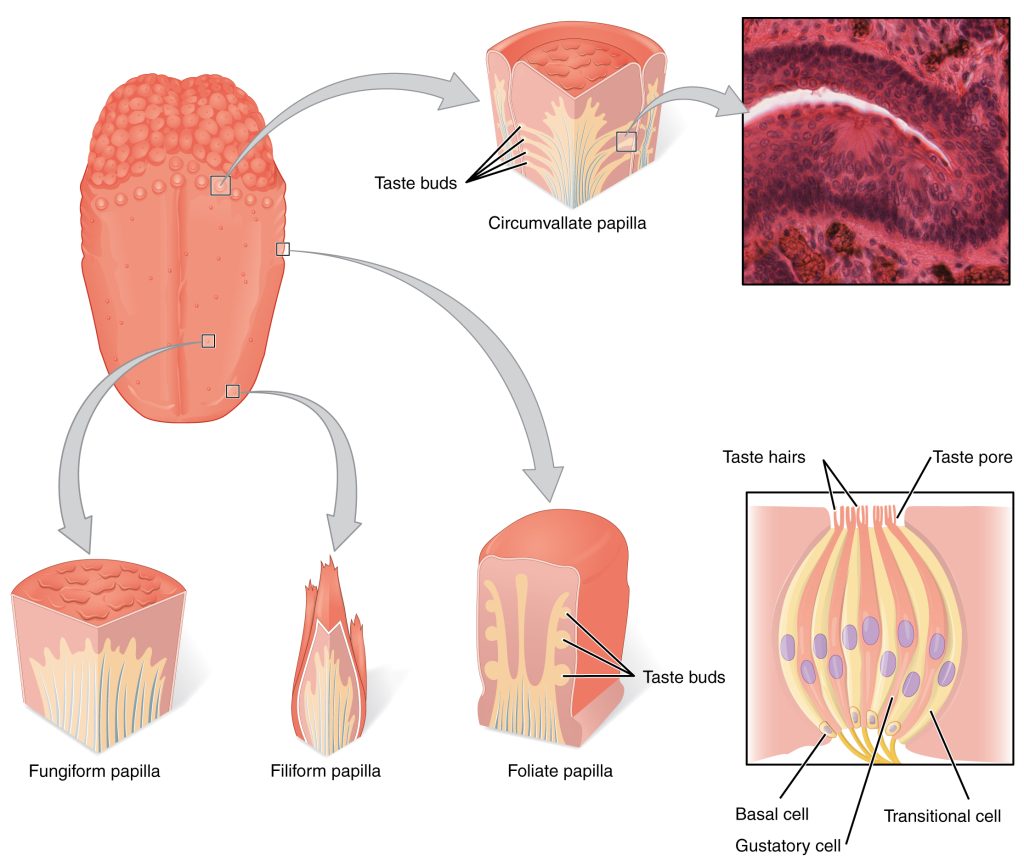

Gustation is the special sense associated with the tongue. The surface of the tongue, along with the rest of the oral cavity, is lined by a stratified squamous epithelium. Raised bumps called papillae (singular = papilla) contain the structures for gustatory transduction. There are four types of papillae, based on their appearance (Figure 9.1): circumvallate, foliate, filiform, and fungiform. Within the structure of the papillae are taste buds that contain specialized gustatory receptor cells for the transduction of taste stimuli. These receptor cells are sensitive to the chemicals contained within foods that are ingested, and they release neurotransmitters based on the amount of the chemical in the food. Neurotransmitters from the gustatory cells can activate sensory neurons in the facial, glossopharyngeal, and vagus cranial nerves.

Only a few recognized submodalities exist within the sense of taste, or gustation. Until recently, only four tastes were recognized: sweet, salty, sour, and bitter. Research at the turn of the 20th century led to recognition of the fifth taste, umami, during the mid-1980s. Umami is a Japanese word that means “delicious taste,” and is often translated to mean savory. Very recent research has suggested that there may also be a sixth taste for fats, or lipids.

Olfaction (Smell)

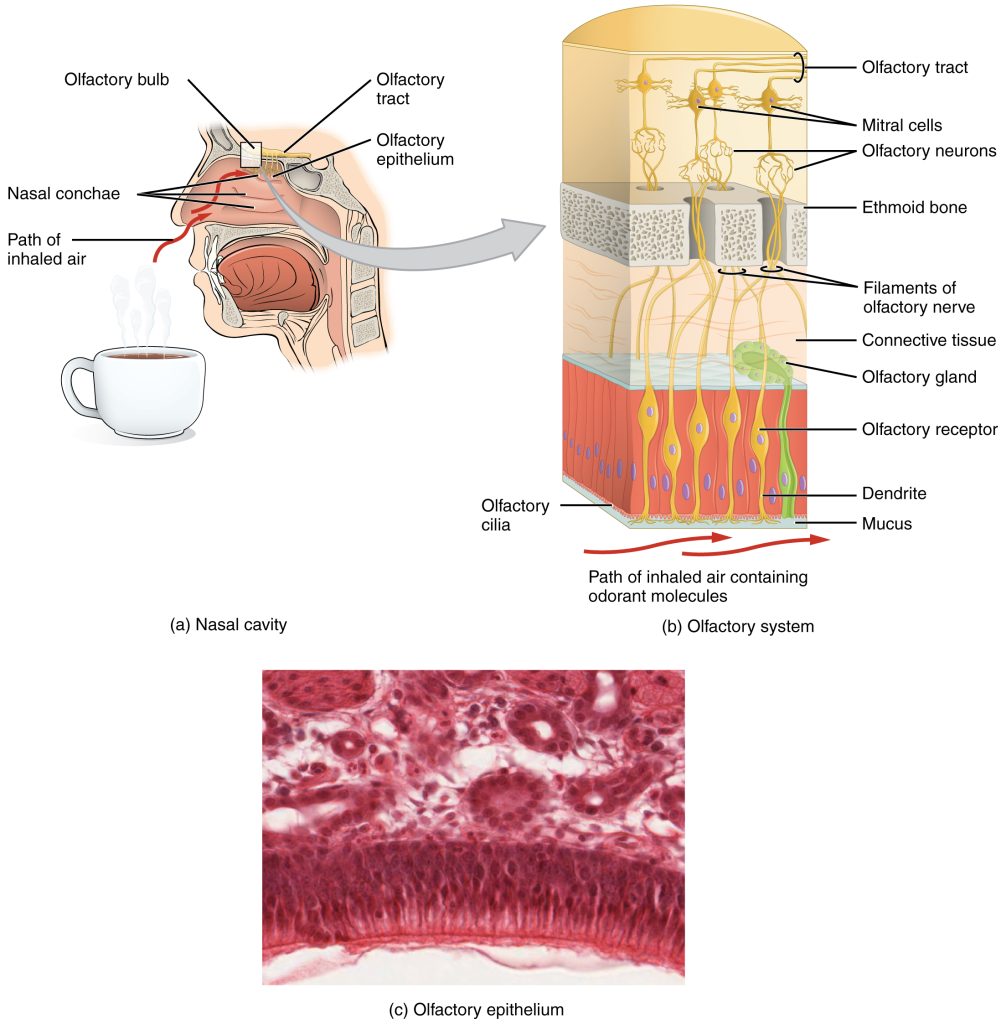

Like taste, the sense of smell, or olfaction, is also responsive to chemical stimuli. The olfactory receptor neurons are located in a small region within the superior nasal cavity (Figure 9.2). This region is referred to as the olfactory epithelium and contains bipolar sensory neurons. Each olfactory sensory neuron has dendrites that extend from the apical surface of the epithelium into the mucus lining the cavity. As airborne molecules are inhaled through the nose, they pass over the olfactory epithelial region and dissolve into the mucus. These odorant molecules bind to proteins that keep them dissolved in the mucus and help transport them to the olfactory dendrites.

The axon of an olfactory neuron extends from the basal surface of the epithelium, through an olfactory foramen in the cribriform plate of the ethmoid bone, and into the brain. The group of axons called the olfactory tract connect to the olfactory bulb on the ventral surface of the frontal lobe. From there, the axons split to travel to several brain regions. Some travel to the cerebrum, specifically to the primary olfactory cortex that is located in the inferior and medial areas of the temporal lobe. Others project to structures within the limbic system and hypothalamus, where smells become associated with long-term memory and emotional responses. This is how certain smells trigger emotional memories, such as the smell of food associated with one’s birthplace. Smell is the one sensory modality that does not synapse in the thalamus before connecting to the cerebral cortex. This intimate connection between the olfactory system and the cerebral cortex is one reason why smell can be a potent trigger of memories and emotion.

Audition (Hearing)

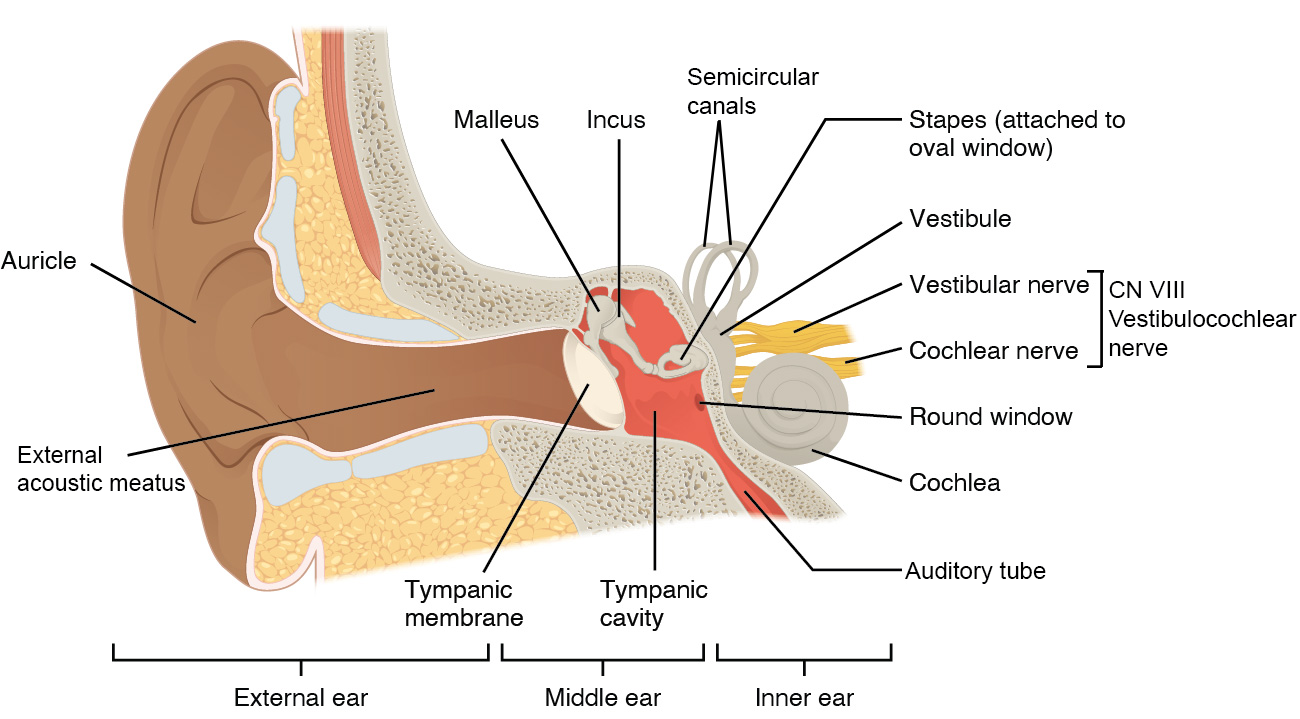

Hearing, or audition, is the transduction of sound waves into a neural signal that is made possible by the structures of the ear (Figure 9.3). The large, fleshy structure on the lateral aspect of the head is known as the auricle. Some sources will also refer to this structure as the pinna, though that term is more appropriate for a structure that can be moved, such as the external ear of a cat. The C-shaped curves of the auricle direct sound waves toward the auditory canal. The canal enters the skull through the external acoustic meatus (external auditory canal) of the temporal bone. At the end of the external acoustic meatus is the tympanic membrane, or ear drum, which vibrates after it is struck by sound waves. The auricle, external acoustic meatus, and tympanic membrane are often referred to as the external ear. The middle ear consists of a space spanned by three small bones called the ossicles. The three ossicles are the malleus, incus, and stapes, which are Latin names that roughly translate to hammer, anvil, and stirrup. The malleus is attached to the tympanic membrane and articulates with the incus. The incus, in turn, articulates with the stapes. The stapes sits in the oval window, which leads to the inner ear. When the stapes vibrates against the oval window, the sound waves are trasnsferred to the inner ear, where they will be transduced into a neural signal. The middle ear is connected to the pharynx through the auditory tube (Eustachian tube), which helps equilibrate air pressure across the tympanic membrane. The auditory tube is normally closed but will pop open when the muscles of the pharynx contract during swallowing or yawning.

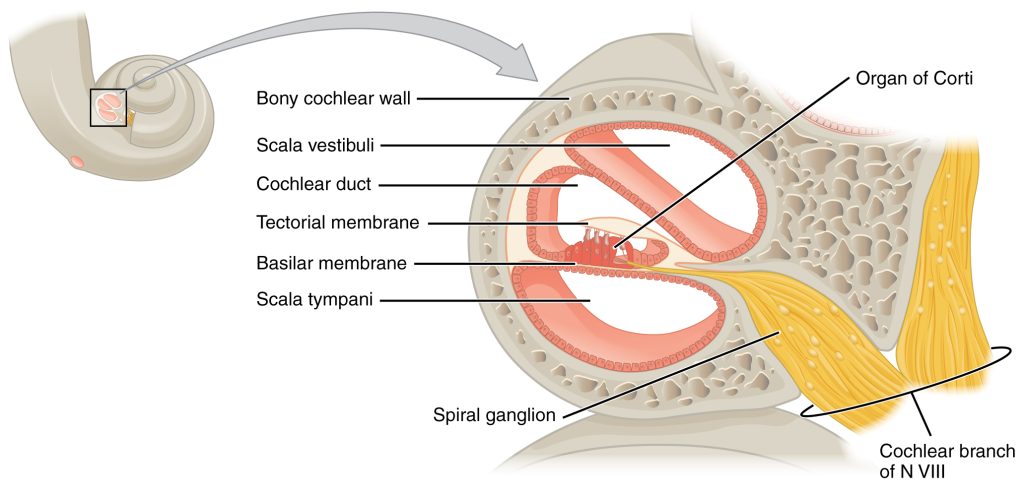

The inner ear is often described as a bony labyrinth, as it is composed of a series of canals embedded within the temporal bone. It has two separate regions, the cochlea and the vestibule, which are responsible for hearing and balance, respectively. The neural signals from these two regions are relayed to the brain stem through separate fiber bundles. However, these two distinct bundles travel together from the inner ear to the brain stem as the vestibulocochlear nerve (CN VIII). Sound is transduced into neural signals within the cochlear region of the inner ear, which contains the sensory neurons of the spiral ganglia. These ganglia are located within the spiral-shaped cochlea of the inner ear.

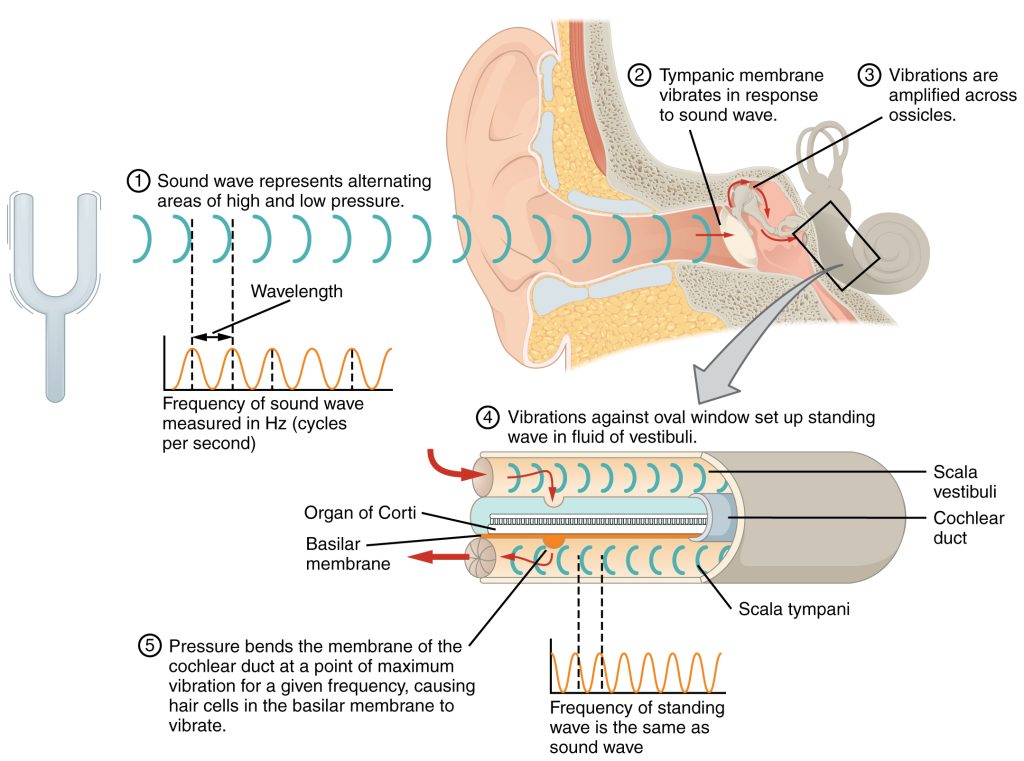

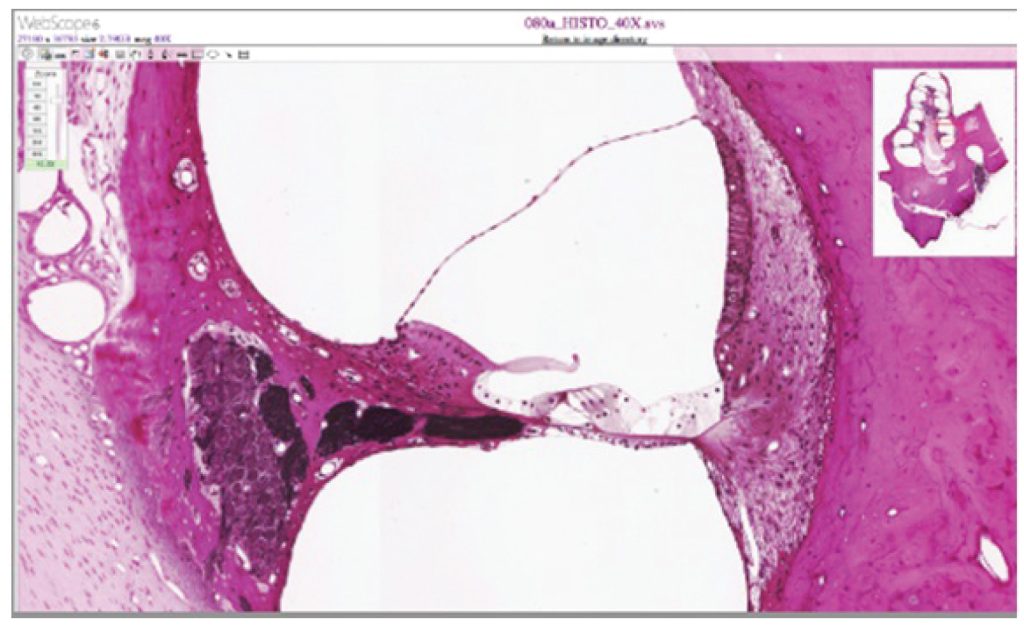

The oval window is located at the beginning of a fluid-filled tube within the cochlea called the scala vestibuli (vestibular duct). The scala vestibuli extends from the oval window, travelling above the cochlear duct, which is the central cavity of the cochlea that contains the sound-transducing neurons. At the uppermost tip of the cochlea, the scala vestibuli curves over the top of the cochlear duct. The fluid-filled tube, now called the scala tympani (tympanic duct), returns to the base of the cochlea, this time travelling under the cochlear duct. The scala tympani ends at the round window, which is covered by a membrane that contains the fluid within the scala. As vibrations of the ossicles travel through the oval window, the fluid of the scala vestibuli and scala tympani moves in a wave-like motion. The frequency of the fluid waves match the frequencies of the sound waves (Figure 9.4). The membrane covering the round window will bulge out or pucker in with the movement of the fluid within the scala tympani.

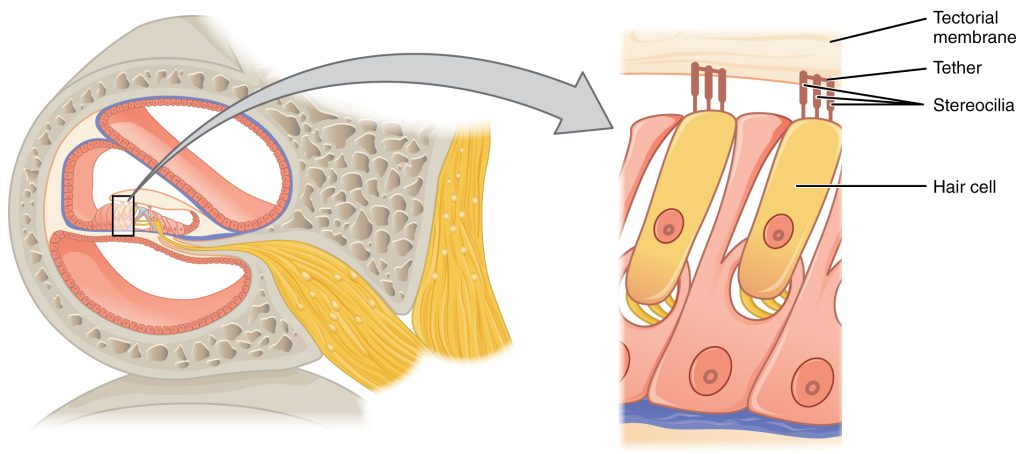

A cross-sectional view of the cochlea shows that the scala vestibuli and scala tympani run along both sides of the cochlear duct (Figure 9.5). The cochlear duct contains several organs of Corti, which transduce the wave motion of the two scala into neural signals. The organs of Corti lie on top of the basilar membrane, which is the side of the cochlear duct located between the organs of Corti and the scala tympani. As the fluid waves move through the scala vestibuli and scala tympani, the basilar membrane moves at a specific spot, depending on the frequency of the waves. Higher frequency waves move the region of the basilar membrane that is close to the base of the cochlea. Lower frequency waves move the region of the basilar membrane that is near the tip of the cochlea.

The organs of Corti contain hair cells, which are named for the hair-like stereocilia extending from the cell’s apical surfaces (Figure 9.6). The stereocilia are an array of microvilli-like structures arranged from tallest to shortest. Protein fibers tether adjacent hairs together within each array, such that the array will bend in response to movements of the basilar membrane. The stereocilia extend up from the hair cells to the overlying tectorial membrane, which is attached medially to the organ of Corti (Figure 9.7). When the pressure waves from the scala move the basilar membrane, the tectorial membrane slides across the stereocilia. This bends the stereocilia either toward or away from the tallest member of each array. When the stereocilia bend toward the tallest member of their array, tension in the protein tethers opens ion channels in the hair cell membrane. This will depolarize the hair cell membrane, triggering nerve impulses that travel down the afferent nerve fibers attached to the hair cells.

Equilibrium (Balance)

Along with audition, the inner ear is responsible for encoding information about equilibrium, the sense of balance. A similar mechanoreceptor—a hair cell with stereocilia—senses head position, head movement, and whether our bodies are in motion. These cells are located within the vestibule of the inner ear. Head position is sensed by the utricle and saccule, whereas head movement is sensed by the semicircular canals. The neural signals generated in the vestibular ganglion are transmitted through the vestibulocochlear nerve to the brain stem and cerebellum.

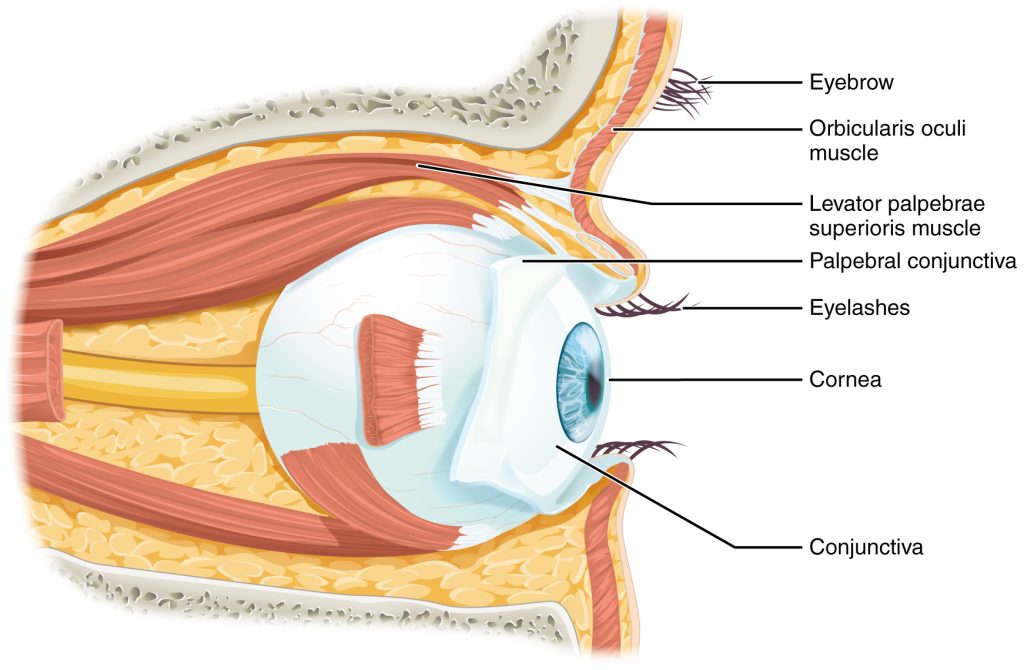

Vision

Vision is the special sense of sight that is based on the transduction of light stimuli received through the eyes. The eyes are located within either orbit in the skull. The bony orbits surround the eyeballs, protecting them and anchoring the soft tissues of the eye (Figure 9.8). The eyelids, with lashes at their leading edges, help to protect the eye from abrasions by blocking particles that may land on the surface of the eye. The inner surface of each lid is a thin membrane known as the palpebral conjunctiva. The conjunctiva extends over the white areas of the eye (the sclera), connecting the eyelids to the eyeball. Tears are produced by the lacrimal gland, located just inside the orbit, superior and lateral to the eyeball. Tears produced by this gland flow through the lacrimal duct to the medial corner of the eye, where the tears flow over the conjunctiva, washing away foreign particles.

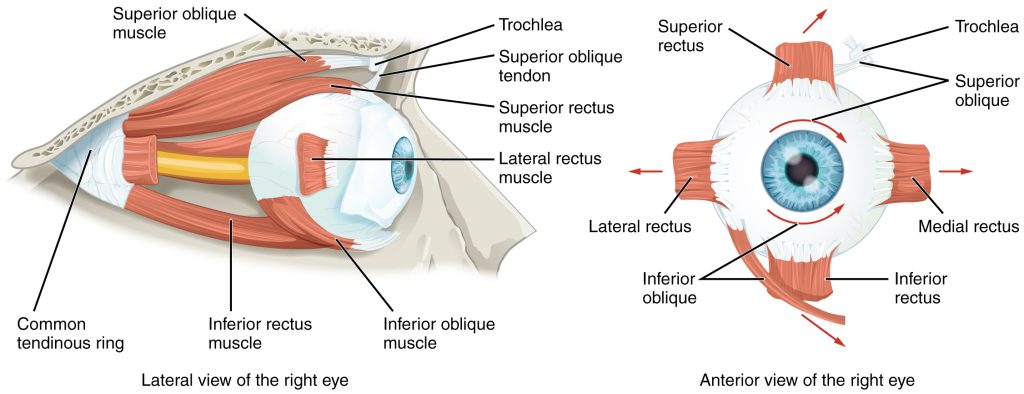

Movement of the eye within the orbit is accomplished by the contraction of six extraocular muscles that originate from the bones of the orbit and insert into the surface of the eyeball (Figure 9.9). Four of the muscles are arranged at the cardinal points around the eye and are named for those locations. They are the superior rectus, medial rectus, inferior rectus, and lateral rectus. When each of these muscles contract, the eye moves toward the contracting muscle. For example, when the superior rectus contracts, the eye rotates to look up. The superior oblique originates at the posterior orbit, near the origin of the four rectus muscles. However, the tendon of the oblique muscles threads through a pulley-like piece of cartilage known as the trochlea. The tendon inserts obliquely into the superior surface of the eye. The angle of the tendon through the trochlea means that contraction of the superior oblique rotates the eye laterally. The inferior oblique muscle originates from the floor of the orbit and inserts into the inferolateral surface of the eye. When it contracts, it laterally rotates the eye, in opposition to the superior oblique. Rotation of the eye by the two oblique muscles is necessary because the eye is not perfectly aligned on the sagittal plane. When the eye looks up or down, the eye must also rotate slightly to compensate for the superior rectus pulling at approximately a 20-degree angle, rather than straight up. The same is true for the inferior rectus, which is compensated by contraction of the inferior oblique. A seventh muscle in the orbit is the levator palpebrae superioris, which is responsible for elevating and retracting the upper eyelid, a movement that usually occurs in concert with elevation of the eye by the superior rectus (see Figure 14.13).

The extraocular muscles are innervated by three cranial nerves. The lateral rectus, which causes abduction of the eye, is innervated by the abducens nerve. The superior oblique is innervated by the trochlear nerve. All of the other muscles are innervated by the oculomotor nerve, as is the levator palpebrae superioris. The motor nuclei of these cranial nerves connect to the brain stem, which coordinates eye movements.

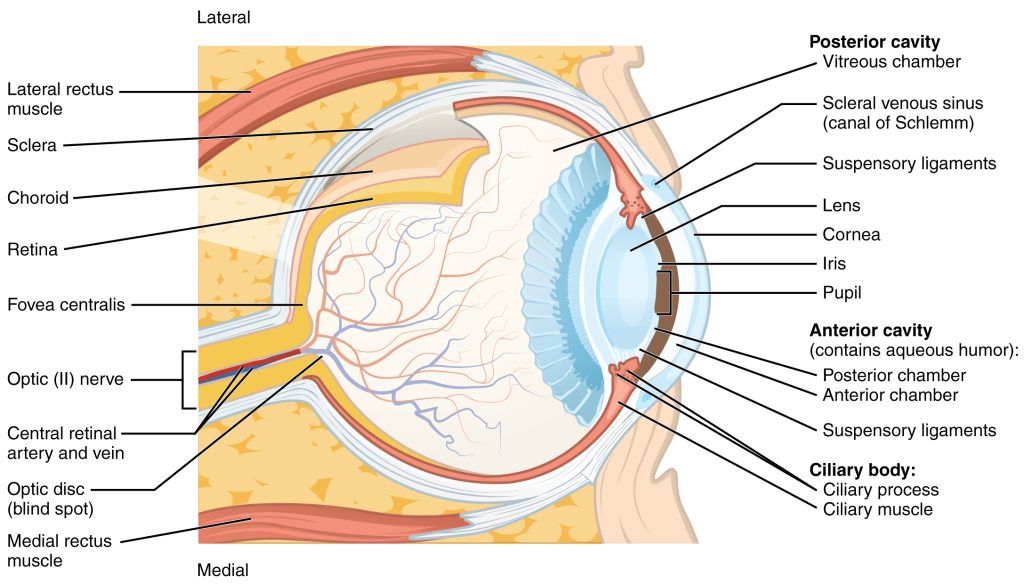

The eye itself is a hollow sphere composed of three layers of tissue. The outermost layer is the fibrous tunic, which includes the white sclera and clear cornea (Figure 9.10). The sclera accounts for five sixths of the surface of the eye, most of which is not visible, though humans are unique compared with many other species in having so much of the “white of the eye” visible. The transparent cornea covers the anterior tip of the eye and allows light to enter the eye. The middle layer of the eye is the vascular tunic, which is mostly composed of the choroid, ciliary body, and iris. The choroid is a layer of highly vascularized connective tissue that provides a blood supply to the eyeball. The choroid is posterior to the ciliary body, a muscular structure that is attached to the lens by suspensory ligaments, or zonule fibers. These two structures bend the lens, allowing it to focus light on the back of the eye. Overlaying the ciliary body, and visible in the anterior eye, is the iris—the colored part of the eye. The iris is a smooth muscle that opens or closes the pupil, which is the hole at the center of the eye that allows light to enter. The iris constricts the pupil in response to bright light and dilates the pupil in response to dim light. The innermost layer of the eye is the neural tunic, or retina, which contains the nervous tissue responsible for photoreception.

The eye is also divided into two cavities: the anterior cavity and the posterior cavity. The anterior cavity is the space between the cornea and lens, including the iris and ciliary body. It is filled with a watery fluid called the aqueous humor. The posterior cavity is the space behind the lens that extends to the posterior side of the interior eyeball, where the retina is located. The posterior cavity is filled with a more viscous fluid called the vitreous humor.

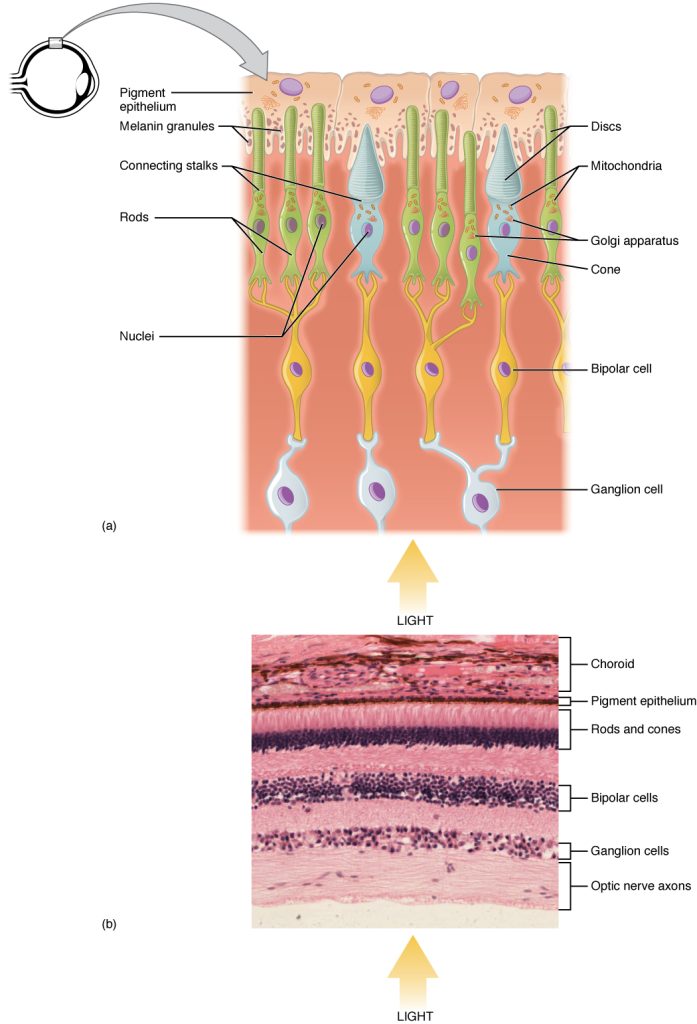

The retina is composed of several layers and contains specialized cells for the initial processing of visual stimuli. The photoreceptors (rods and cones) change their membrane potential when stimulated by light energy. The change in membrane potential alters the amount of neurotransmitter that the photoreceptor cells release onto bipolar cells in the outer synaptic layer. It is the bipolar cell in the retina that connects a photoreceptor to a retinal ganglion cell (RGC) in the inner synaptic layer. There, amacrine cells additionally contribute to retinal processing before an action potential is produced by the RGC. The axons of RGCs, which lie at the innermost layer of the retina, collect at the optic disc and leave the eye as the optic nerve (see Figure 9.10). Because these axons pass through the retina, there are no photoreceptors at the very back of the eye, where the optic nerve begins. This creates a “blind spot” in the retina, and a corresponding blind spot in our visual field.

Note that the photoreceptors in the retina (rods and cones) are located behind the axons, RGCs, bipolar cells, and retinal blood vessels (Figure 9.11). A significant amount of light is absorbed by these structures before the light reaches the photoreceptor cells. However, at the exact center of the retina is a small area known as the fovea. At the fovea, the retina lacks the supporting cells and blood vessels, and only contains photoreceptors. Therefore, visual acuity, or the sharpness of vision, is greatest at the fovea. This is because the fovea is where the least amount of incoming light is absorbed by other retinal structures (see Figure 9.10). As one moves in either direction from this central point of the retina, visual acuity drops significantly. The difference in visual acuity between the fovea and peripheral retina is easily evidenced by looking directly at a word in the middle of this paragraph. The visual stimulus in the middle of the field of view falls on the fovea and is in the sharpest focus. Without moving your eyes off that word, notice that words at the beginning or end of the paragraph are not in focus. The images in your peripheral vision are focused by the peripheral retina, and have vague, blurry edges and words that are not as clearly identified. As a result, a large part of the neural function of the eyes is concerned with moving the eyes and head so that important visual stimuli are centered on the fovea.

Unless otherwise indicated, this chapter contains material adapted from chapter 14 in Anatomy and Physiology 2e (on OpenStax), by Betts, et al. and is used under a a CC BY 4.0 international license. Download and access OpenStax Anatomy and Physiology for free at https://openstax.org/details/books/anatomy-and-physiology-2e/