5 Subject Headings

Overview

By shifting focus from classification to subject headings, this chapter continues the discussion of subject metadata. As with the previous chapter, it provides a short introduction to the topic and its relation to DEI and access, and it describes two methods librarians can use to improve the inclusivity of their catalogs, along with case studies of their implementation.

Introduction to subject headings

Library subject headings are types of controlled vocabularies, which are “list[s] or database[s] of terms in which all terms or phrases representing a concept are brought together.”[1] Controlled vocabularies allow users to distinguish between words and terms that represent different concepts but use identical spelling (i.e., homographs). Joudrey, Taylor, and Wisser use the example “Mercury,” which can be used to refer to “a liquid metal, a planet, a car, or a Roman god.”[2] Conversely, these vocabularies allow libraries to collocate synonymous or near-synonymous words and terms (e.g., “Association football” is a variant of “Soccer”[3]) and differences in spelling or inflection (e.g., “Woodworking” is a variant of the LCSH “Woodwork”[4]). Although controlled vocabularies are not used exclusively to convey subject content, that will be the focus of this chapter, with special attention paid to the Library of Congress Subject Headings (LCSH), a large, comprehensive controlled vocabulary that is intended to describe subject matter in all areas of knowledge.

This chapter cannot begin to summarize the wide range of opinions related to LCSH and DEI comprehensively; however, three issues identified by Olson are worth discussing at length: exclusions, marginalizations, and distortions.[5] First, the author noted the issue of headings that are excluded, such as “Wicca,” which, at that time, lacked a heading and was placed under “Witchcraft,” making it difficult to find materials specific to Wicca. Also, “Witchcraft” is a narrower term of “Occultism” thus placing “Wicca” in this diabolical category. Next, the author discusses marginalizations, which occur when a subject is placed “outside of the cultural mainstream—making it ‘other’ [emphasis in original]. […] Examples of this practice are headings for groups of people consisting only of adjectives, such as: Handicapped, Poor and Aged [emphasis in original]. What is included is what differentiates these groups from the mainstream. What is excluded is the fact that they are people.”[6] Finally, Olson discusses distortions, “[a] more subtle systemic problem [that] uses the structure of subject heading list to shift the meaning of a term in a particular direction.”[7] For example, the narrower headings for the subject heading “Feminism” fail to capture the diversity of feminist thought and movements by not including headings for liberal feminism as well as many of feminism’s more radical variants. As a result, the LCSH portrays feminism as “a dated white, middle-class liberal movement with a few in-your-face splinter groups.”[8]

Working within LCSH

As with LCC and DDC, LCSH is intended to be updated indefinitely to adapt to changing social norms, the dynamic nature of language, and the evolving needs of library users. Subject Authority Cooperative Program (SACO), a division of the Program for Cooperative Cataloging, provides libraries with the opportunity to participate directly in these updates. Created in the 1990s,[9] SACO allows members to propose changes to existing subject headings, which are then reviewed by Library of Congress staff who decide whether to approve the changes.[10] Member libraries are expected to submit ten to twelve proposals annually; however, those unable to submit this number may also collaborate with other libraries through designated SACO funnels,[11] which are “group[s] of libraries (or catalogers from various libraries) that have joined together to contribute subject authority records for inclusion in the Library of Congress Subject Headings.” Funnels can either be focused on a specific subject area or represent libraries in a geographic region.[12]

An overview of the proposal process is on the Library of Congress website: “Process for Adding and Revising Library of Congress Subject Headings” (https://www.loc.gov/aba/cataloging/subject/lcsh-process.html). First, search the Library of Congress Subject Authority File (https://www.loc.gov/aba/cataloging/subject/lcsh-process.html) to ensure that the proposal has not already been effectively addressed by existing LCSHs. Second, research the subject of the proposed heading, focusing on how the subject is defined and described and what terms are used for it in the literature. Third, create or update the record for the proposal in accordance with rules provided in the Subject Headings Manual (SHM) (https://www.loc.gov/aba/publications/FreeSHM/freeshm.html), LC’s official documentation for subject authority records. Finally, submit the proposal using the instructions found in SHM under H 200: Preparation of Subject Heading Proposals (https://www.loc.gov/aba/publications/FreeSHM/H0200.pdf). Proposals are then reviewed by the Policy, Training, and Cooperative Programs Division (PTCP), with rejected proposals announced on SACO’s Summaries of Decisions from Subject Editorial Meetings (https://www.loc.gov/aba/pcc/saco/cpsoed/cpsoeditorial.html), posted on the LCSH approved lists. Proposals also can be made by non-library workers, or libraries that are not SACO members, who may recommend changes by contacting the PTCP directly.[13] The Library of Congress recommends subscribing to the RSS feed Library of Congress Subject Headings Approved Lists, which can be found on its website.[14]

We recommend several practices for all libraries using LCSH to follow:

- Evaluate choices critically when assigning subject headings.

- Follow updates to LCSH.

- Connect with your stakeholders (i.e., users, library staff, and community members) and involve them in the process when applicable.

- Know your options for recommending changes or additions to LCSH, either as a SACO or non-SACO member library.

- Consider using alternative subject headings (see below) if the problem cannot be adequately addressed using LCSH.

Case study: Changing existing headings

A well-documented case study of changing headings through the SACO process took place with the revision of the LCSH “Illegal aliens” (see concise timeline of events in Figure 5.1). Although the term “illegal aliens” was widely accepted to describe undocumented immigrants in the past, in recent years, critics increasingly viewed the term as derogatory,[15] and in 2013 the Associated Press announced that it was discontinuing its use.[16] In early 2014 the recently founded Coalition for Immigration Reform, Equality and DREAMERs (CoFIRED), a student activist group at Dartmouth College, reached out to its library to request that the term be removed from its catalog.[17]

In July of that year, Dartmouth’s library suggested updating five subject headings that included the term “illegal aliens” through SACO.[18] The Library of Congress initially rejected the proposal on the ground that “Illegal aliens is an inherently legal heading,” and “[m]ixing an inherently legal concept with one that is not inherently legal leads to problems with the structure and maintenance of LCSH, and makes assignment of headings difficult.”[19] In June 2015 a representative from the Cataloging and Metadata Management Section (CaMMS)[20] Subject Analysis Committee communicated with one of the librarians at Dartmouth to discuss additional options for addressing the issue. At the 2015 ALA Annual Meeting, the committee agreed to review the headings in question and recommend changes if warranted. At the 2016 ALA Midwinter Meeting, the “Resolution on Replacing the Library of Congress Subject Heading ‘Illegal Aliens’ with ‘Undocumented Immigrants’” was submitted to ALA Council for consideration. With strong support from several professional organizations within ALA, the resolution passed “nearly unanimously.”[21] In March 2016 the Library of Congress announced that it was replacing the subject heading “Illegal aliens” with “Noncitizens” and “Unauthorized immigration.”[22]

But the story doesn’t end here. In an unusually high-profile affair for the normally low-key field of metadata and cataloging, the proposed changes drew ire of several members of the United States Congress, who criticized the Library of Congress’s revision as partisan.[23] An initial attempt to prevent the update was HR 4926, “Stopping Partisan Policy at the Library of Congress Act,” which was introduced by Representative Diana Black and would have required retention of the terms, but it was not voted on.[24] Ultimately, Congress did not require retention of the headings but included a provision in the 2017 appropriations that directed the Library of Congress to make the process for approving changes to subject headings more transparent.[25] While the headings were eventually changed in 2021,[26] many individual libraries decided to revise the term locally in the interim. The next section briefly discusses how some libraries updated the subject headings in their catalogs independently of SACO and the official LCSH.

| 2013 |

|

|---|---|

| 2014 | |

| 2015 |

|

| 2016 | |

| 2017 |

|

| 2021 |

|

Alternative subject headings

In addition to LCSH, libraries can use alternative headings or even full alternative controlled vocabularies. This allows libraries to apply headings to local records without having to go through the SACO revision process, as well as tailor headings to local needs or specific niches.

Due to the long delay in replacing the LCSH “Illegal aliens,” many libraries and library consortia updated their discovery systems locally. In June 2019 the CaMMS Subject Analysis Committee created the SAC Working Group on Alternatives to LCSH “Illegal Aliens,” to study and report on this work. In September and October of 2019 the group distributed a survey for libraries and identified four common methods that were used to address this locally: “adding a new heading to the record in a local or MARC field without removing the corresponding “Illegal aliens” subject heading[,] replacing the “Illegal aliens” subject heading in bibliographic records[,] creating a local authority record in the backend library system[,] or creating a local authority record in the discovery system.”[36] It proceeds to discuss pros and cons of the various methods that libraries should consider when planning similar projects. For example, retaining the initial heading maintains its function as an access point but also keeps the offensive terminology visible to users. The group notes that some discovery systems can solve this problem by retaining the original heading as an access point while displaying only the updated version publicly. Thus, “when LC revises this heading in the official LCSH, libraries using this approach can use their traditional authority control methods to update bibliographic records as they normally would.”[37]

Another option is to go beyond individual headings and embrace an alternative controlled vocabulary. This can help address broad subjects for which existing systems are largely inaccurate, considered offensive, or simply insufficient for describing specific demographic groups. Libraries can either adopt existing alternative systems or, as described in the case study below, actively develop new ones. An example of an alternative controlled vocabulary is the Homosaurus (https://homosaurus.org/), “an international linked data vocabulary of LGBTQ+ terms. Designed to enhance broad subject term vocabularies, the Homosaurus is a robust and cutting-edge thesaurus that advances the discoverability of LGBTQ+ resources and information.”[38] First developed by the IHLIA LGBT Heritage in 1997 for local use,[39] it has been revised as three official versions—1 (2013), 2 (2019), and 3 (2021)—and has been changed from a flat to a hierarchical structure and made compatible with linked data technologies. As of August 2023, updates to the vocabulary were made by its editorial board.[40]

We recommend several steps for libraries considering alternative subject headings:

- Identify a subject area that may benefit from alternative subject headings.

- Research existing alternative subject headings.

- Create a new system if existing alternative subject headings are inadequate.

- Implement the headings into your library’s workflow and discovery layers.

The following section discusses several things to consider during this process.

Implementing alternative subject headings

After your institution has done the necessary research and decided to use alternative headings, the next step is to incorporate them into your systems and workflows. For consistency, it is important to document the circumstances in which to apply alternative headings, as well as how to do so. Below are some questions to help with your decision making and documentation.

- Which records will be targeted for alternative headings?

Will you target all new records, all existing records, or records for selected collections or types of resources? Will you consider MARC records and non-MARC records? - Which alternative headings will be used?

For consistent reference, it is a good idea to compile a list of problematic headings that you wish to supplement or replace with alternative terms. For examples, refer to OCLC’s local subject remapping template,[41] the Triangle Research Libraries Network’s list of terms currently overlaid,[42] Cataloging Lab’s list of Problem Headings[43], and the University of Manitoba’s Changes to Library of Congress Subject Headings Related to Indigenous Peoples.[44] - How will you identify the targeted records?

Will you use an automated process to identify records containing specified problematic headings? When automation is not possible, you may wish to perform searches for certain terms to understand their frequency. The results of your searches may help prioritize your efforts. - How will you update the targeted records?

To make the changes, will you use an automated process, such as an integrated library system (ILS) normalization rule that automatically applies alternative headings to records containing problematic headings?[45] Will you use a batch editing tool such as MarcEdit, OpenRefine, or spreadsheets to make global changes? Moreover, will catalogers and metadata creators be instructed to add alternative terms manually in certain scenarios? - Which headings will display and/or function as an access point?

Will you add alternative terms as supplemental headings, replace problematic headings with alternative terms, or retain problematic headings for discovery but hide them from public view? The strategy of adding supplemental headings provides “the maximum subject and keyword access to bibliographic records.”[46] However, you may wish to replace problematic headings entirely if your users are likely to consider them harmful. The third strategy combines the benefits of the first two but also depends on the functionality of your discovery platform. - Which field or element will be used to record alternative headings?

In MARC records, you could use a 650 field with a second indicator 7 and a subfield $2 indicating the source of the term, or you could use a locally defined field. In non-MARC records, depending on the granularity of your chosen scheme, you may be able to use the same subject element no matter the source of the term, or you may need to use a customized element. If possible, record a Uniform Resource Identifier (URI) for the alternative term.[47] - How will records for new materials be addressed?

Will alternative headings be applied continuously through an automated process? Will you assign alternative headings whenever new records are created? Will you perform a periodic review of existing records? - Will the alternative headings be revised in the future?

Will periodic reviews and revisions of the alternative headings take place? Will the library have a process for reporting feedback to technical services? For example, if a user informs a public service librarian of an issue regarding the new system, does the library have a process to record this information for future consideration?

Case study: Subject headings for Iowa Indigenous Peoples

The Iowa State University Library began exploring methods to improve the inclusivity of library metadata that would be feasible with our limited time and budget. By researching previous and ongoing projects, we became aware of various initiatives involving the creation of vocabularies for Indigenous groups that used the names preferred by these communities.[48] We decided that similar efforts would be valuable for the land that constitutes the modern state of Iowa. For the next two years, we researched preferred names for Indigenous nations related to Iowa and proposed alternative terms to the LCSH terms available for these peoples.[49] We then consulted with these Indigenous communities to find out whether the proposed terms were appropriate. We offered reciprocity in the form of a LibGuide that highlighted books of interest from Iowa State’s collections,[50] our digital press’s DEI commitment to work with authors from minoritized groups or in non-English languages, and free Interlibrary Loan for these communities.

We received responses from 62 percent (13 out of 21) of the communities we contacted. Responses indicated most of the proposed terms were acceptable, but we did receive several spelling corrections and different preferred terms. A list of these vocabulary terms and their LCSH counterparts is maintained and publicly available in a Google Sheet.[51] We chose to supplement the existing LCSH in our Alma MARC records and digital collections metadata rather than replace it. Some of our rationale for taking this approach included ensuring searchability as well as possible future work where we would suppress display of the outdated LCSH terms. For now, the LCSH terms remain on our records, in anticipation of the Library of Congress’s plan to improve its terms for Indigenous groups[52]

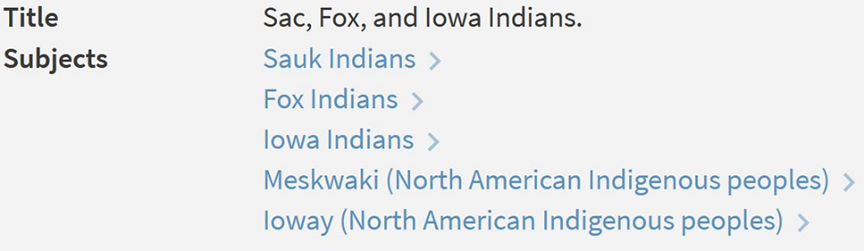

Figure 5.2 provides an example of two of our local supplemental terms for the Ioway and the Meskwaki; the LCSH equivalent for the former is Iowa Indians.[53] For the latter, catalogers often applied two LCSH terms, Fox Indians and Sauk Indians.[54]

| 650 ## | $a Ioway (North American Indigenous peoples) $2 local |

|---|---|

| 650 ## | $a Meskwaki (North American Indigenous peoples) $2 local |

Figures 5.3 and 5.4 compare the change in public display before and after the supplemental headings were added. A set of Alma normalization rule stanzas are available in GitHub;[55] Alma libraries are welcome to use them to include culturally appropriate subject terms for these Iowa Indigenous nations.

Conclusion

This chapter provided an overview of DEI and library subject headings. Following a brief introduction, it discussed how libraries can increase the inclusivity of their headings both with LCSH and by using, or even developing, alternative subject headings. Two case studies were discussed in detail: the update to the LCSH “Illegal aliens” and the Subject Headings for Iowa Indigenous Peoples project at the Iowa State University Library.

General

- Homosaurus vocabulary site

https://homosaurus.org/ - Library of Congress Linked Data Service

https://id.loc.gov/ - SACO – Subject Authority Cooperative Program, Program for Cooperative Cataloging

https://www.loc.gov/aba/pcc/saco/ - African American Subject Funnel Project

https://www.loc.gov/aba/pcc/saco/aframerfun.html - African American Studies Librarians Interest Group (AASLIG): SACO African American Funnel Project

https://acrl.libguides.com/c.php?g=761433&p=7312552 - Hawaii/Pacific Subject Authority Funnel Project

https://www.loc.gov/aba/pcc/saco/hawaiifun.html - The Cataloging Lab, List of Alternative Vocabularies

https://cataloginglab.org/list-of-alternative-vocabularies/ - The Cataloging Lab, List of Problem Headings

https://cataloginglab.org/problem-lcsh/ - OCLC, Create Locally Preferred Subjects for Display and Search Expansion

https://help.oclc.org/Discovery_and_Reference/WorldCat_Discovery/Display_local_data/Create_locally_preferred_subjects_for_display_and_search_expansion - Triangle Research Libraries Network, TRLN Discovery Subject Remapping

https://trln.org/resources/subject-remapping/

Related to the Iowa State University NAIP Project

- Alma normalization rules, add-supplemental-heading-for-american-indian-community.txt

https://go.iastate.edu/JAMTVS - Resources and Services for Iowa Indigenous Peoples

https://go.iastate.edu/UAREL3 - Subject Headings for Iowa Indigenous peoples

https://go.iastate.edu/JTJXQL

- Daniel N. Joudrey, Arlene G. Taylor, and Katherine M. Wisser, The Organization of Information, Fourth edition, Library and Information Science Text Series (Santa Barbara, CA: Libraries Unlimited, 2018), 630. ↵

- Joudrey, Taylor, and Wisser, Organization of Information, 486. ↵

- “Soccer,” Library of Congress Subject Headings (LCSH), Library of Congress, last modified January 6, 2011, https://id.loc.gov/authorities/subjects/sh85123840.html. ↵

- “Woodwork,” LCSH, last modified June 8, 2015, https://id.loc.gov/authorities/subjects/sh85148022.html. ↵

- Hope A. Olson, “Difference, Culture and Change: The Untapped Potential of LCSH,” Cataloging & Classification Quarterly 29, no. 1–2 (2000): 61, https://doi.org/10.1300/J104v29n01_04. ↵

- Olson, “Difference, Culture and Change,” 61. ↵

- Olson, 61. ↵

- Olson, 62. ↵

- Alva T. Stone, “The LCSH Century: A Brief History of the Library of Congress Subject Headings, and Introduction to the Centennial Essays,” Cataloging & Classification Quarterly 29, no. 1–2 (2000): 7. https://doi.org/10.1300/J104v29n01_01. ↵

- “About the SACO Program,” SACO - Subject Authority Cooperative Program, Library of Congress, accessed August 14, 2023, https://www.loc.gov/aba/pcc/saco/about.html. ↵

- “Joining the SACO Program,” SACO, accessed September 5, 2023, https://www.loc.gov/aba/pcc/saco/join.html. ↵

- “SACO Funnels,” SACO, https://www.loc.gov/aba/pcc/saco/funnels.html. ↵

- “Process for Adding and Revising Library of Congress Subject Headings,” Library of Congress, accessed August 24, 2023, https://www.loc.gov/aba/cataloging/subject/lcsh-process.html. ↵

- “Subscribe to E-Mail Newsletters and Alerts,” Library of Congress, accessed May 16, 2024, https://loc.gov/subscribe/. ↵

- Erin Blakemore, “The Library of Congress Will Ditch the Subject Heading ‘Illegal Aliens,’” Smithsonian Magazine, March 29, 2016, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/library-congress-will-ditch-subject-heading-illegal-aliens-180958599/. ↵

- Paul Colford, “‘Illegal Immigrant’ No More,” Announcements, AP Definitive Source, The Associated Press (blog), April, 2, 2013, https://blog.ap.org/announcements/illegal-immigrant-no-more. ↵

- Violet B. Fox, “Cataloging News,” Cataloging & Classification Quarterly 54, no. 7 (October 2, 2016): 506–07, https://doi.org/10.1080/01639374.2016.1218707. ↵

- Fox, “Cataloging News,” 507. ↵

- “Summary of Decisions, Editorial Meeting Number 12,” Program for Cooperative Cataloging, Library of Congress, December 15, 2014, https://www.loc.gov/aba/pcc/saco/cpsoed/psd-141215.html. ↵

- CaMMS was a section of the American Library Association division Association for Library Collections and Technical Services (ALCTS). The division merged with the Library Leadership and Management Association (LLAMA) and the Library Information Technology Association (LITA) in 2020 to form the new division Core. ↵

- Fox, “Cataloging News,” 508. ↵

- Library of Congress, Library of Congress to Cancel the Subject Heading “Illegal Aliens”. March 22, 2016, https://www.loc.gov/catdir/cpso/illegal-aliens-decision.pdf. ↵

- Jasmine Aguilera, “Another Word for ‘Illegal Alien’ at the Library of Congress: Contentious,” New York Times, July 22, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/07/23/us/another-word-for-illegal-alien-at-the-library-of-congress-contentious.html. ↵

- Violet Fox, Report of the SAC Working Group on Alternatives to LCSH “Illegal Aliens”: Submitted to the ALA/ALCTS/CaMMS Subject Analysis Committee, SAC Working Group on Alternatives to LCSH “Illegal aliens,” June 19, 2020, 2, http://hdl.handle.net/11213/14582. ↵

- 115 Congressional Record 4033 (2017), https://www.congress.gov/crec/2017/05/03/CREC-2017-05-03-bk3.pdf. ↵

- American Library Association, “ALA Welcomes Removal of Offensive ‘Illegal Aliens’ Subject Headings,” November 12, 2021, https://www.ala.org/news/2021/11/ala-welcomes-removal-offensive-illegal-aliens-subject-headings. ↵

- Colford, “‘Illegal Immigrant’ No More.” ↵

- Fox, “Cataloging News,” 506–07. ↵

- Fox, 507. ↵

- “Summary of Decisions,” Program for Cooperative Cataloging. ↵

- Fox, “Cataloging News,” 508. ↵

- Fox, 508. ↵

- Library of Congress, Cancel the Subject Heading. ↵

- 115 Congressional Record 4033 (2017). ↵

- American Library Association, “ALA Welcomes Removal.” ↵

- Kelsey George, Erin Grant, Cate Kellett, and Karl Pettitt, “A Path for Moving Forward with Local Changes to the Library of Congress Subject Heading ‘Illegal Aliens,’” Library Resources & Technical Services 65, no. 3 (2021): 89. https://doi.org/10.5860/lrts.65n3.84. ↵

- George et al., “Path for Moving Forward,” 91. ↵

- “About,” Homosaurus, accessed August 14, 2023, https://homosaurus.org/about. ↵

- “IHLIA” was derived from the organization’s initial name “Internationaal Homo/Lesbisch Informatiecentrum en Archief.” The acronym was retained after the renaming. R. J. Davidson, “Consensus Social Movements: Strategic Interaction in Dutch LGBTI Politics” (PhD thesis, Amsterdam, Amsterdam Institute for Social Science Research, 2021), xiii, https://hdl.handle.net/11245.1/cc522a57-8c30-44fe-9633-ac132dc2491d. ↵

- “About,” Homosaurus. ↵

- “Create Locally Preferred Subjects for Display and Search Expansion,” OCLC, last modified July 1, 2024, https://help.oclc.org/Discovery_and_Reference/WorldCat_Discovery/Display_local_data/Create_locally_preferred_subjects_for_display_and_search_expansion. ↵

- Kelly Farrell, “TRLN Discovery Subject Re-Mapping Program,” TRLN: Triangle Research Libraries Network, October 29, 2020, https://trln.org/2020/10/trln-discovery-subject-re-mapping-program/. ↵

- “Problem LCSH,” Cataloging Lab, accessed June 16, 2022, https://cataloginglab.org/problem-lcsh/. ↵

- Christine Bone, Brett Lougheed, Camille Callison, Janet La France, and Terry Reilly, Changes to Library of Congress Subject Headings Related to Indigenous Peoples: For Use in the AMA MAIN Database, 2017, http://hdl.handle.net/1993/31177. ↵

- In this context, normalization refers to “[t]he action of removing unimportant differences from data, especially text, to simplify subsequent processing.” “Normalization,” in A Dictionary of Computer Science, ed. Andrew Butterfield, Gerard Ekembe Ngondi, and Anne Kerr (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016), https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199688975.001.0001/acref-9780199688975-e-6416. ↵

- George et al., “A Path for Moving Forward,” 90. ↵

- i.e., “[a]n identifier for some resource available on the Internet, such as a webpage, digital document, or application.” “URI,” in High Definition: A-Z Guide to Personal Technology (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2006), https://search.credoreference.com/articles/Qm9va0FydGljbGU6MTc2OTQ2NQ==?aid=100725. ↵

- For select examples, see Richard E. Sapon-White, “Retrieving Oregon Indians from Obscurity: A Project to Enhance Access to Resources on Tribal History and Culture” (paper, IFLA World Library and Information Congress, Wroclaw, Poland, 2017), https://library.ifla.org/id/eprint/1621/; and Christine Bone and Brett Lougheed, “Library of Congress Subject Headings Related to Indigenous Peoples: Changing LCSH for Use in a Canadian Archival Context,” Cataloging & Classification Quarterly 56, no. 1 (2018): 83–95, https://doi.org/10.1080/01639374.2017.1382641. ↵

- This summary is based on our research previously published in Heather Campbell, Christopher S. Dieckman, Nausicaa L. Rose, and Harriet E. Wintermute, “Improving Subject Headings for Iowa Indigenous Peoples,” Library Resources & Technical Services 66, no. 1 (2022): 48–59, https://doi.org/10.5860/lrts.66n1.48. ↵

- “Resources and Services for Iowa Indigenous Peoples,” Iowa State University Research and Course Guides, Iowa State University Library, last modified March 26, 2024, https://go.iastate.edu/UAREL3. ↵

- Iowa State University Library Metadata Services, Subject Headings for Iowa Indigenous Peoples, June 20, 2022, https://go.iastate.edu/JTJXQL. ↵

- “Subject Headings for Indigenous Peoples,” Cataloging and Acquisitions, Library of Congress, last modified July 26, 2023, https://www.loc.gov/aba/cataloging/subject/indigenous.html. ↵

- “Iowa Indians,” LCSH, last modified June 7, 2011, https://id.loc.gov/authorities/subjects/sh85067858.html. ↵

- “Fox Indians,” LCSH, last modified April 14, 2011, https://id.loc.gov/authorities/subjects/sh85051119.html; and “Sauk Indians (Algonquian),” LCSH, last modified November 23, 2021, https://id.loc.gov/authorities/subjects/sh85117717. Note that the parenthetical suffix with Algonquin was added in LCSH in 2021 after this phase of our work had been completed. ↵

- Metadata Services @ Iowa State University, “add-supplemental-heading-for-american-indian-community.txt," GitHub repository, 2021, https://go.iastate.edu/JAMTVS. ↵