5 Aural Skills

Aural skills (a.k.a. "ear training") courses are linked to music theory courses on many college campuses. The theory/aural skills sequence generally takes four semesters and begins in the fall of the first year. Many schools offer some sort of fundamentals of music theory course in the first semester for those who are unable to pass a placement test in the summer prior to admission.

You do not need to enroll in an advanced placement theory course to be successful with theory and aural skills in college. Those who do so or have been studying piano will certainly have an advantage, but it is not a necessity. There are many online resources available (see Appendix A) to help you get your ears ready for success!

Skills Practiced and Assessed in Aural Skills

Your multiple semesters of aural skills will be dedicated to similar skills, but in an increasing level of difficulty. In the beginning, patterns will be short (perhaps only two notes) and part of the major or minor scale or perhaps one measure in 4/4 time, for example. You will be asked to read/perform, detect errors in given musical listening examples, and dictate (write down what you hear). The difficulty level will increase quickly and this is a skill-based course, so it is important that you practice. There are no shortcuts!

Sightsinging/Sightreading

Sightsinging, or sightreading, refers to the ability to pick up a piece of music and being able to perform it without first hearing it or without help from accompaniment or any other instrument. For choir, band, and orchestra musicians (Western European traditions), music literacy refers to the ability to translate notation into sound (reading) and sound into notation (notating). These skills are important as a musician. Being able to produce the music with your voice demonstrates your ability to internally 'hear' it (often referred to as audiation) and, therefore, more easily and accurately put it into your instrument.

Studying music has many parallels to learning a language. When we’re young, we absorb lots of sounds, then begin to try to imitate what we hear. Then, people label things for us (This is a cat. The cat says “meow.”) and we begin to try out a few words. Those words eventually become sentences. Again, adults read picture books to us so we can associate the words we know to the pictures. Only after that labeling do we learn how to recognize words on a page. The letters are abstract symbols in much the same way notes are symbols. The final step—in a nutshell—is to read and write. A lot had to happen before you to the letters meant something, yet I bet your first band or piano book had symbolic notation on page one or soon after!

The ability to read standard notation is integral and authentic to participation in the performing ensembles that have been so carefully nurtured in schools in the United States. Musicians in this tradition must be able to do more than imitate. Unfortunately, the pressure of performance often leads to choirs that are taught exclusively by rote. In other words, the teacher feeds singers the “answers” to the “test” from a piano. Band and orchestra musicians are taught to read symbolic notation, but are often taught “by eye” rather than through sound before symbol. In this case, players may be able to decode (press certain buttons when they see certain symbols), but being able to press the correct keys on an instrument in response to notation does not confirm that the performer comprehends what it is they are playing or singing. One parallel might be to compare a French class and learning French in a diction course. In the diction course, you will learn how to pronounce each consonant and vowel so that you can sound like you speak the language, but not have any idea what you’re saying. These musicians will be slow in learning new works (and will probably require a music teacher to do so).

Knowing that a note on the third line of treble clef is “B” means you have a way of talking about music and understanding the theory behind it. Praxis, or practice (doing music), needs to come before theory. Knowing that a note on the third line of treble clef is B does not make you a better musician. Improvisation is not just for jazz musicians; it is being creative in the moment. It is a fundamental aspect of musicianship requiring you to think in music. We recommend several resources for practice later in this volume, but an easy way to get started if you have never been encouraged is to simply use a familiar rhythm and give yourself the choice of one of two pitches to use for each note. You can increase the number of notes or start from a tonal pattern (outlining a major triad—do mi sol, for example) and change the rhythm. You’re improvising!

In the beginning, music reading should focus on just rhythm or just pitch. You will quickly be required to multi-task and perform both together, but one of the first steps on the road to being able to read notation is interval identification. As described in the previous chapter, an interval is the distance between two notes. Being able to identify intervals aurally (by ear) is a foundational skill for later reproducing the intervals vocally, stringing longer numbers of pitches, (patterns), together and, finally, reading melodies. Being familiar with intervals is the foundation for almost everything you will do in your aural skills courses (and later in your job!).

Error Detection

One of the most important skills you will need as a music educator is the ability to hear what is wrong (detect the errors) so that you are able to fix them. Error detection is about picking out and correcting wrong notes, rhythms, or anything else in music. You’ll begin with finding wrong rhythms or pitches in a melody or and eventually move on to hearing incorrect pitches in chords, intonation errors, etc.

Rhythmic, Melodic and Harmonic Dictation

Dictation refers to writing down what you hear. You’ll begin with short patterns of pitches or single measures of rhythms and move to longer phrases, two-part exercises and, eventually, progressions of four-part chords. Listening to and echoing short rhythmic or melodic patterns is a great way to prepare yourself for this skill.

Prepare Yourself!

Again, learning music is similar to learning a language. First, you must get the sounds in your ears. Only then can you reproduce them yourself and, eventually, be able to translate what you hear into written notation. Before you enter a degree program, it would be helpful to be able to sing intervals accurately and perform simple melodies at sight (this applies to instrumentalists as well as vocalists). You will find several different ways to label pitches and rhythms in this chapter.

Symbols of Duration/Rhythmic Notation

Rhythms are patterns of sound in time, a basic element of all music. Beat is the unit division of musical time. The beat is the steady pulse that might make you want to tap your feet or move to it. That’s good—rhythm has to be felt in the body!

Meter

Meter is the way we group the beats. More formally, it is the beats organized into recognizable/recurring accent patterns. We group eggs by the dozen. We group days by the week. We group beats into twos and threes. That is meter. There are two basic kinds of meter: duple and triple. In other words, you can either march to duple (two beats = strong-weak) or sway to it with triple meter (three beats = strong-weak-weak). Each of the beats can then also be divided into either two (simple meter) or three (compound meter). Here are a few examples:

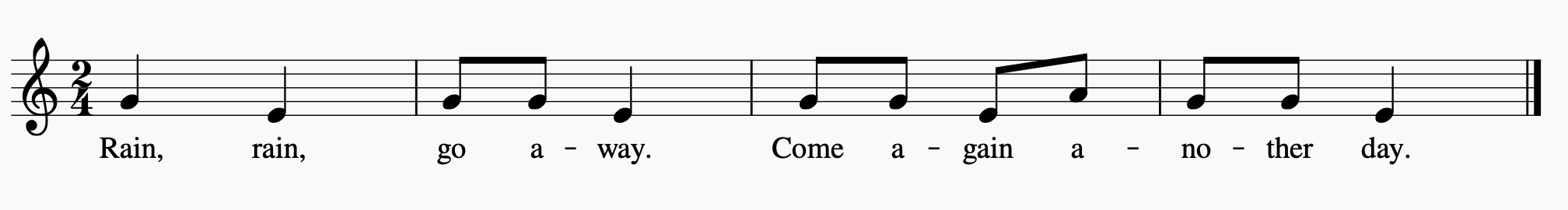

Rain, Rain Go Away

Duple simple (two beats in a measure, beats are divided into two)

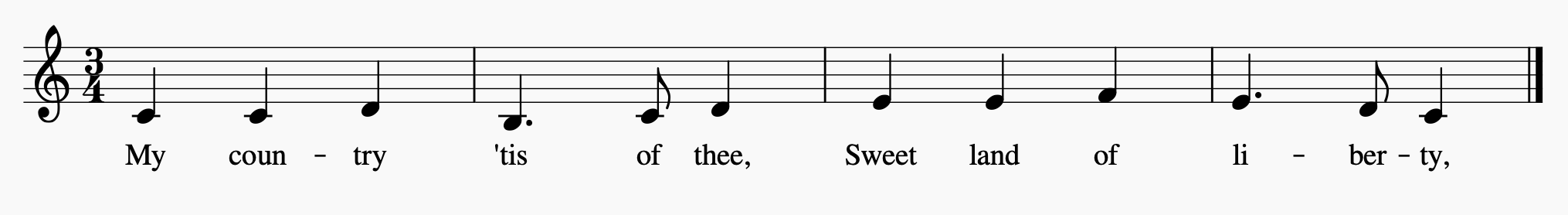

My Country ‘Tis of Thee

Triple simple (three beats in a measure, beats are divided into two).

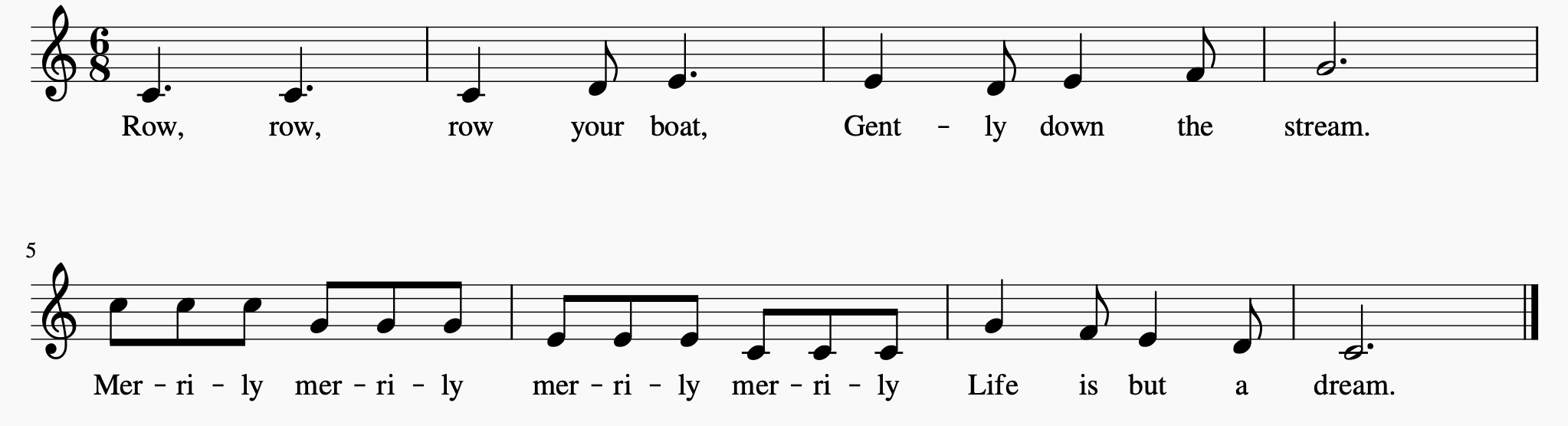

Row Your Boat

Duple compound (two beats per measure, beats are divided over three)

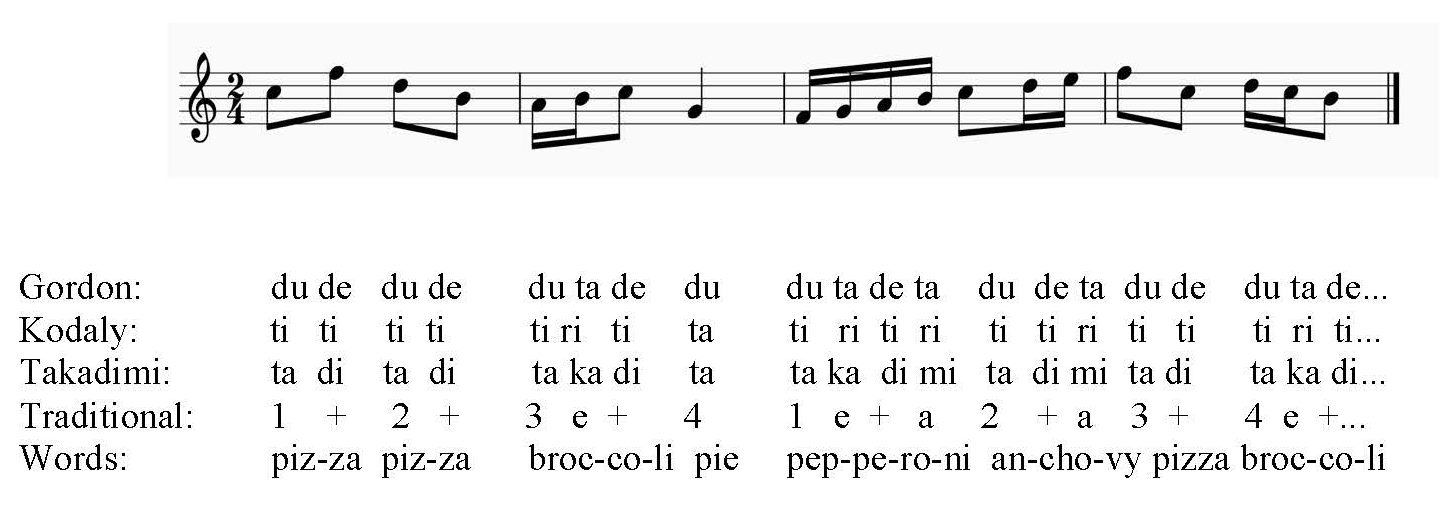

Counting Systems

There are several different counting systems in use. They exist to aid both in counting and in time-keeping. The system used in aural skills may vary depending on the college or university you choose. This is certainly a question you could ask when you visit. Fortunately, it is not only easy to switch back and forth between each, but actually beneficial for you as a future teacher. On the pages that follow, you will be introduced to Gordon’s Music Learning Theory, the Kodály method, Orff principles, the Eastman system, Takadimi, and (of course) the traditional numbers counting method. You will likely recognize some of these from your music classes at school.

Music Learning Theory

Edwin E. Gordon, former professor at Temple University in Philadelphia, founded the Gordon Institute of Music and created Music Learning Theory. Gordon was a highly published and well-respected leader in the world of music education research as well as the creator of many standardized tests for music aptitude and music achievement.

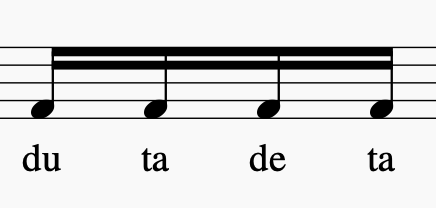

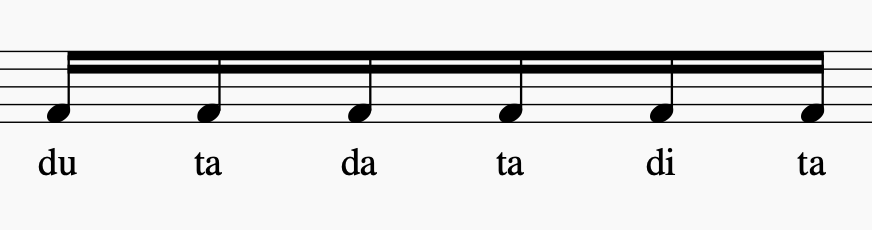

Gordon’s Music Learning Theory is an all-inclusive method for teaching musicianship that has as its cornerstone audiation, or the ability to hear the music in your mind. The system employs the use of patterns to practice “sound before symbol.” It is concerned with beat function rather than notation/note values. In other words, he promoted “rote before note” by focusing on what you hear (“du” signals the beginning of a beat, which might be divided into two or four) rather than what you see (half note = two beats — which isn’t even always true!). Remember, it is important to be able to hear, not just decode.

Kodály

Developed in Hungary in the early 20th century, composer Zoltan Kodály originally designed this system to create a national curriculum for his country so that all students would continue to learn national folk songs and be learning the same skills in their music classes even if they moved to a new school or new city.

You may have been introduced to ta and ti ti in your elementary music classroom experience. Here, the syllables are assigned to specific note values (in other words, ta = quarter note and ti = eighth note). It is an aural (relating to the ear) system that focuses on beat division. Some teachers still use these syllables at the elementary level, but it is not sophisticated enough to take a student through the more complicated rhythms they may later encounter in high school and collegiate programs. Books published in recent years show that Kodály practitioners have embraced Takadimi.

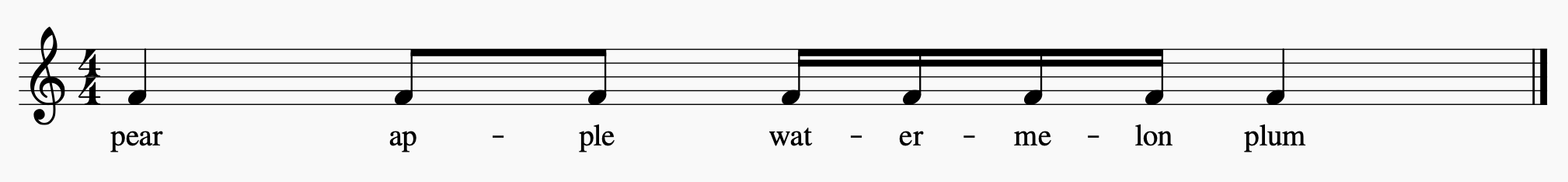

Orff

Orff practitioners often use the rhythm of language in their teaching because singing, speaking, and movement are all naturally connected and a developmentally appropriate step in music learning. For example, eighth notes may be “ap-ple” and sixteenth notes “wa-ter-me-lon.” The natural flow of language makes it easy for young students to feel the stress and perform rhythms before reading notation. Like Gordon and Kodály, it is a beat-based system. Unfortunately, apple, berry, Peter, water, and carrot all = two eighth notes, so while there is value in being able to get to music making quickly, so many labels for the same rhythm may cause confusion as students progress in their training.

Eastman System

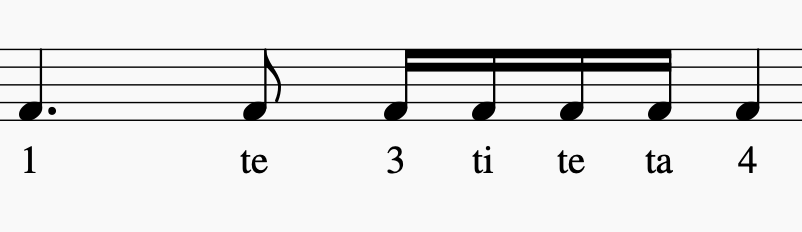

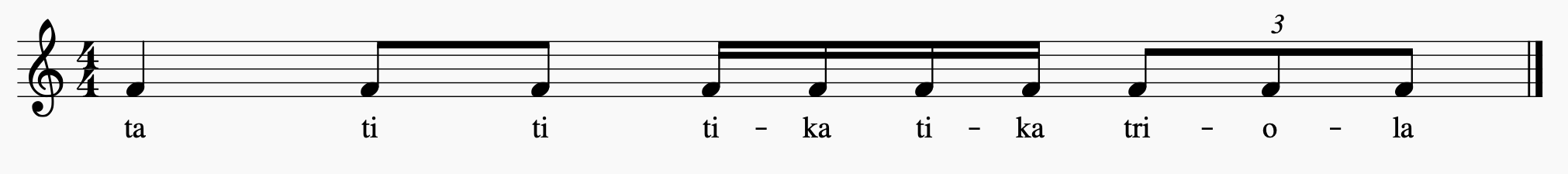

As you may have guessed, the Eastman System was designed at Eastman School of Music in New York. It employs both numbers and syllables. Here are the five rules of the system:

- All notes on a beat get the beat number.

- Notes on the upbeat are “te.”

- A note on the second third of a beat is “la” and a note on the third third of a beat is “le.” (triplets go “…la le.”)

- A note on the second fourth of a beat is “ti.” (sixteenth notes are “…ti te ta.”)

- All other notes are “ta.”

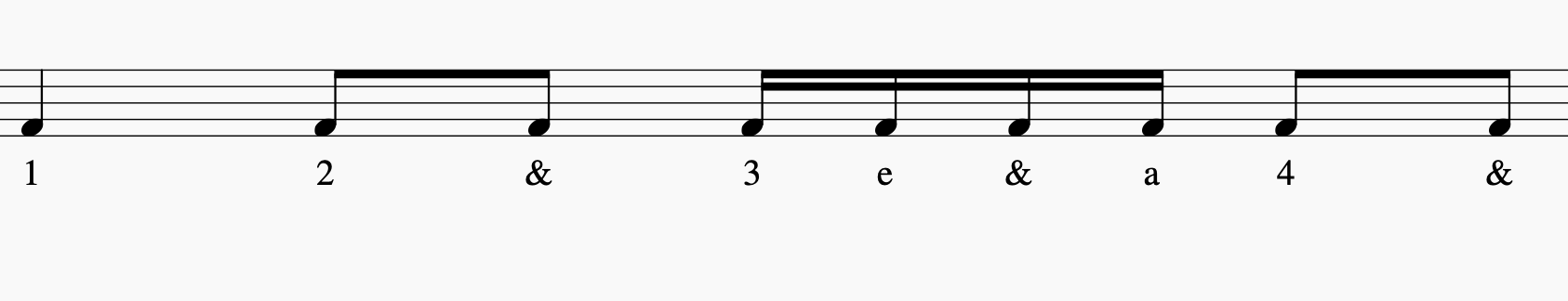

Numbers

Our guess is that you’re already familiar with this one! The tradition of numbers, developed in American public schools, is still the most common method in use. This system focuses on counting the beats within a measure and is found in many band/orchestra series books and beginning piano books. This system focuses on sight before sound and unfortunately, does not necessarily begin with aural understanding as with Takadimi.

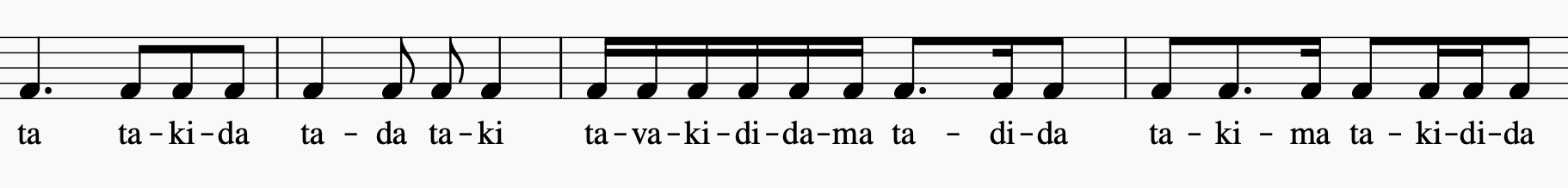

Takadimi

Designed by Hoffman, Pelto, and White in 1996, this system has been taken to new heights by Dr. Carol Krueger. Her book, Progressive Sight Singing, and accompanying online materials are valuable resources (that we’ll help you find later in the book)! Takadimi has been referred to as a “womb to tomb” system because it can be used by the very young and never “breaks,” no matter how complex the rhythm becomes.

In this system, syllables are assigned to a location within a beat. The syllables were drawn from the vocalizations used for the division of a pulse in North Indian tabla playing. Ta is always on the beat and di is the second half of the beat. When the beat is subdivided into four parts, ta and di are in the same place, but the subdivisions are labeled with ta-ka-di-mi. In compound meter, when the beat is divided into three, there are three syllables: ta (which is still on the beat), ki and da (see above).

Takadimi is beat-oriented rather than notation-based. It’s an aural system, which works well because music is an aural art. Our ears need to make sense of it before we can begin to understand notation. It’s about note relationships. Syllables are not symbol-specific. Ta is not always the quarter note; the beat might be the eighth note or the half note, etc. For example, the time signatures [latex]\mathbf{^2_4}[/latex] and [latex]\mathbf{^2_2}[/latex] sound the same. In compound meter, ta = the dotted eighth. If you were like us, you were taught that [latex]\mathbf{^6_8}[/latex] time = six beats per measure and the eighth note gets the beat. That’s not how music works! In [latex]\mathbf{^6_8}[/latex], there are two beats in a measure and each beat is divided into three.

Many band and orchestra directors prefer the numbers system. Takadimi, however, lends itself easily to tonguing and vowels that promote an open throat. Students comfortable with Takadimi can easily translate to numbers when it comes time for band. It is very easy to replace ta with the number of the beat when and if the placement of the beat within a measure becomes important. There is one instrumental lesson book series that employs sound before sight using Takadimi: Jump Right In. It was designed by none other than Edwin Gordon and has been carried on by professors at the Eastman School of Music.

Comparing the Systems

No matter what system you use, you will benefit from getting your body involved and practicing in a variety of different ways. For example, you could pat the beat while speaking the syllables. Trying walking the beat while clapping the rhythm. Conduct while you tap with the other hand. The way to master this skill is through effective drill! The good news is there are really relatively few rhythmic patterns to learn. The Takadimi illustration shows almost all of the possibilities within one beat. Melodic patterns are another story…

Symbols of Melody/Pitch Notation

Pitch refers to the speed of vibration or, more simply, sounds that are higher and lower. While rhythm refers to duration, pitch is a tonal element. When we put the two together, we have melody.

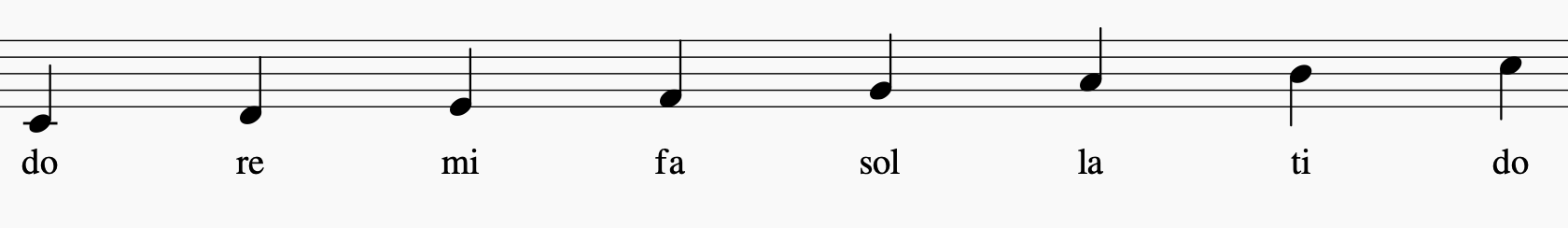

Labeling Pitches

Moveable do is the most common method of solfège singing in the U.S. In moveable do, do is the key note of the piece. In other words, if the song is in the Key of F, F is do. The picture above happens to show a major scale in the key of C. It is the easiest place to begin because it contains no sharps or flats. The example above and those that follow are all shown in the key of C. It is called a relative system because the focus is on the relationship between the pitches rather than an absolute system, where the label is always the label. For example, in fixed do, the pitch C is always do and D is always re, etc. regardless of what key the piece is in, much like the way the note names (A, B, C, D, E, F, G) never change. Truly, you will need to be able to use both relative and absolute systems but we already have note names and moveable do is the aural system (ear before eye, sound before sight, rote before note)!

Sometimes a number system is employed in which do = 1, re = 2, mi = 3, etc. to designate the scale degree. This maybe become confusing as numbers are often used as counting syllables (1 + 2 + 3 +....) and when an accidental is added, one must sing “flat seven” or “sharp four”—not terribly pleasing vowels and impossible to accomplish if one is, for example, trying to sing fast sixteenth notes! The vowels used in solfège are much better for singing. Researchers have not concluded that one method is better than another, but Gordon, Kodály, and Orff all employed moveable do in their pedagogy. If your brain attaches solfège syllables to pitches and patterns, you will more easily be able to recognize when it feels or doesn’t feel right and be able to read or, later, write what you hear quickly.

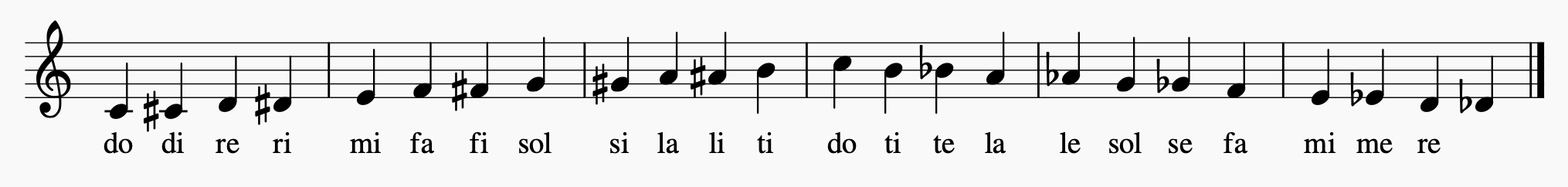

Chromatic Scale

There are 12 half steps in each octave. As you go up the scale, vowels turn to “i” (ee phonetically). As you come back down, lowered pitches are labeled ending in “e” (eh) with one exception—re becomes ra.

The hand signs used in several methods for teaching music to young people were attributed to John Curwen, but developed by Sarah Glover. They make your brain work just a little bit harder and give you something to attach to the aural sensation. After all, the voice is an instrument you can’t see.

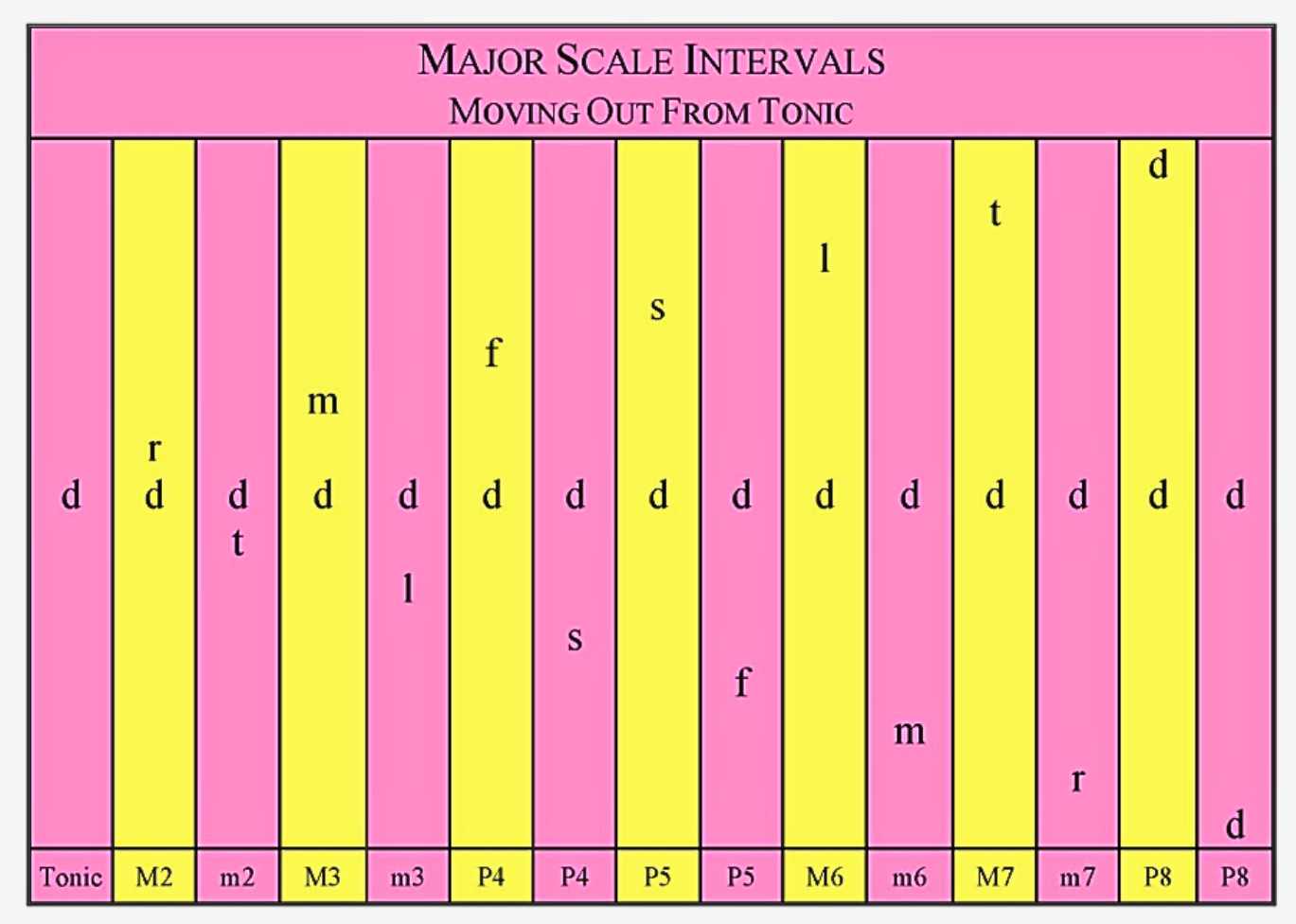

You may have noticed in the previous chapter that all diatonic intervals ascending from do are either major (2nd, 3rd, 6th, 7th) or perfect (4ths and 5ths). All diatonic intervals descending from do are minor (2nd, 3rd, 6th, 7th) or perfect (4ths and 5ths). Interval recognition will not always begin on do, but it’s a good place to start. If you don’t comprehend the interval instantly, try making the first note you hear do and either singing up the scale until you get to the correct pitch or singing down to it.

You hear arpeggios (do-mi-sol-do-sol-mi-do) in music all of the time. They are often the basis of large ensemble warm-ups. These notes are your friends and every other note in a scale is only one step higher or lower—re is a whole step (and often wants to resolve to) do. Fa is but a tiny half step above mi. La is just one step higher than sol and ti will bring you right back to do (as the famous tune from The Sound of Music reminds us). These are what we usually call “tendency tones” in the scale; this is how the notes “behave” in standard chord progressions.

You hear arpeggios (do-mi-sol-do-sol-mi-do) in music all of the time. They are often the basis of large ensemble warm-ups. These notes are your friends and every other note in a scale is only one step higher or lower—re is a whole step (and often wants to resolve to) do. Fa is but a tiny half step above mi. La is just one step higher than sol and ti will bring you right back to do (as the famous tune from The Sound of Music reminds us). These are what we usually call “tendency tones” in the scale; this is how the notes “behave” in standard chord progressions.

Reading melodies at sight using the notes in the major scale is the focus of much of the first semester aural skills. A good way to practice would be to listen to patterns on a neutral syllable (like “la” or something played on an instrument) and echo what you hear on solfège syllables. Once you are good at that skill, challenge yourself to label the intervals as well. You will see websites and maybe even books that list songs to help you be able to recognize or reproduce intervals, like “Here Comes the Bride” for a P4 or “My Bonnie Lies Over the Ocean” for a M6. The scale is a better tool and will make you a faster and more accurate reader. You will not have time to stop while you’re reading and think about that song and you may find that you can make a P4 sound just like the P5 of “Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star” in your head under the pressure of a quiz or test!

Additional Resources

Cleland, Kent D. and Dobrea-Grindahl, Mary. (2021). Developing Musicianship through Aural Skills: A Holistic Approach to Sight Singing and Ear Training (3rd edition). Routledge.

Krueger, Carol. (2023). Progressive Sight Singing (3rd edition). Oxford.

American Orff-Schulwerk Association. https://aosa.org/.

The Gordon Institute for Music Learning. https://giml.org/.

Krueger, Progressive Sight Singing 4e Resources. https://learninglink.oup.com/access/krueger4e.

Organization of American Kodaly Educators. https://www.oake.org/.

Takadimi. https://www.takadimi.net/.