4 Music Theory

In this chapter, we will introduce you to the music theory skills and knowledge that you may want to become familiar with before taking your music entrance and placement exams and starting your music degree.

To experience the greatest success as a new music major, it will benefit you to know some basic music theory before you begin your collegiate program. What is meant by music theory? It is the systematic study of the musical elements including, but not limited to pitch, rhythm, melody, harmony, form, and notation.

To get your best start, you will want to be able to identify and understand the following

- Notation on the treble and bass clef

- The music alphabet and piano keyboard

- How to construct major and minor scales

- Key signatures

- Intervals

- Triads

- Symbols of duration (rhythm)

- Meter and time signatures

If this is all new to you, we have included a basic primer on these topics in this chapter and a list of websites and free online resources is provided in Section 5. In addition, your school music teacher, private lesson teacher, or other local musician can also likely help you prepare in these areas.

You should also keep in mind, if these topics seem too far out of your league or uninteresting to you, perhaps a majoring in music isn’t for you—but keep reading—there is much more information to follow.

Treble and Bass Clefs with Notation

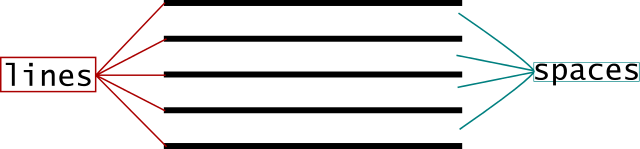

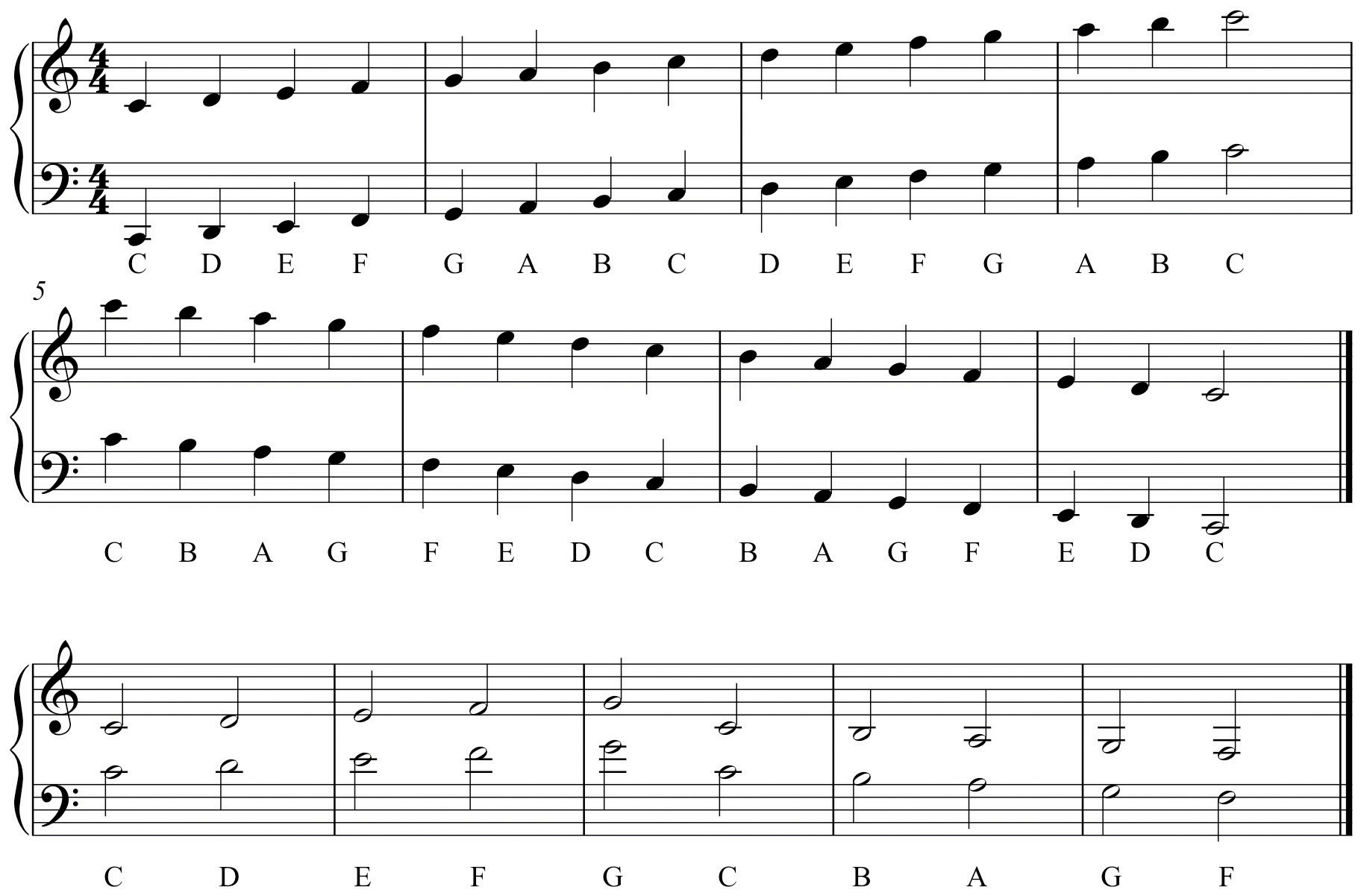

To begin we will start with basic music theory and explore simple travel and bass clef notation. A music staff is a series of five lines and four spaces that each represent a different musical pitch. The lines and spaces are numbered from bottom to top; the bottom line is the first line and the top line is the fifth line. The plural of staff is staves.

A grand staff is a combination of two staves put together, usually a treble clef (G clef) on the top and a bass clef (F clef) on the bottom staff. These clefs tell us the names of the notes on the staff.

The names of musical notes go from A to G and then start over. The lines and spaces of each staff do the same thing, but ‘A’ is not conveniently located at the bottom of either staff.

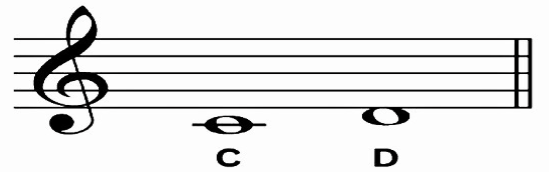

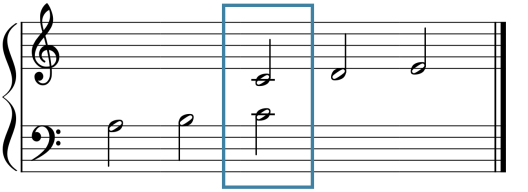

You probably notice that there is a gap in note names between the treble and bass staves of the Grand Staff. The B is placed on the staff directly above the top line of the bass staff, and the D is placed on the space directly below the bottom line of the treble staff. But what about C?

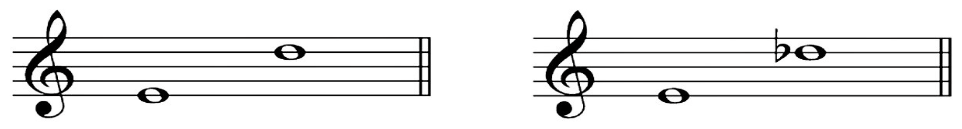

When we run out of lines and spaces above or below either staff, we use what are called ledger lines to temporarily make the staff bigger. Instead of adding a whole new line that runs the width of the page, we shorten it to just around that one note. The C in between the two staves is called middle C, and can be written on either the top or bottom staff, like you see here:

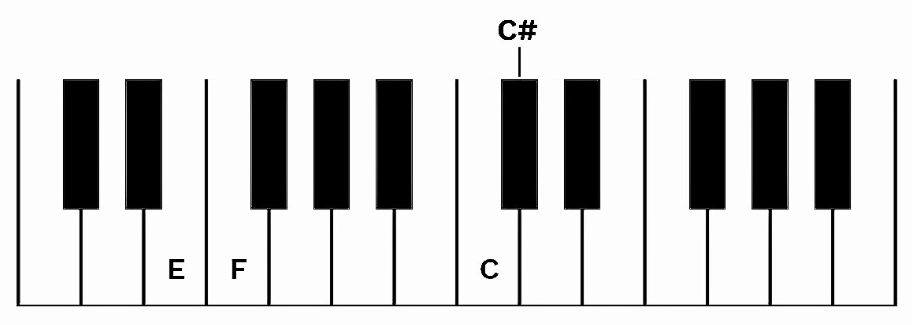

The Music Alphabet and the Piano Keyboard

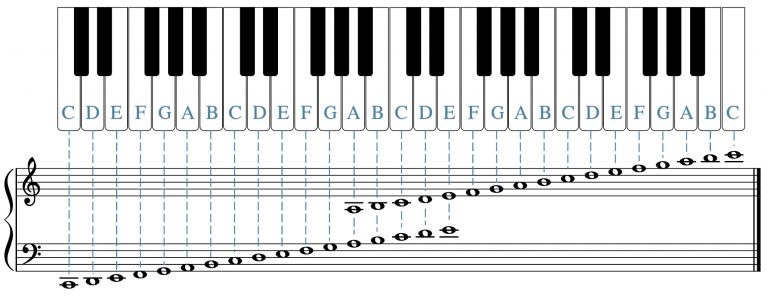

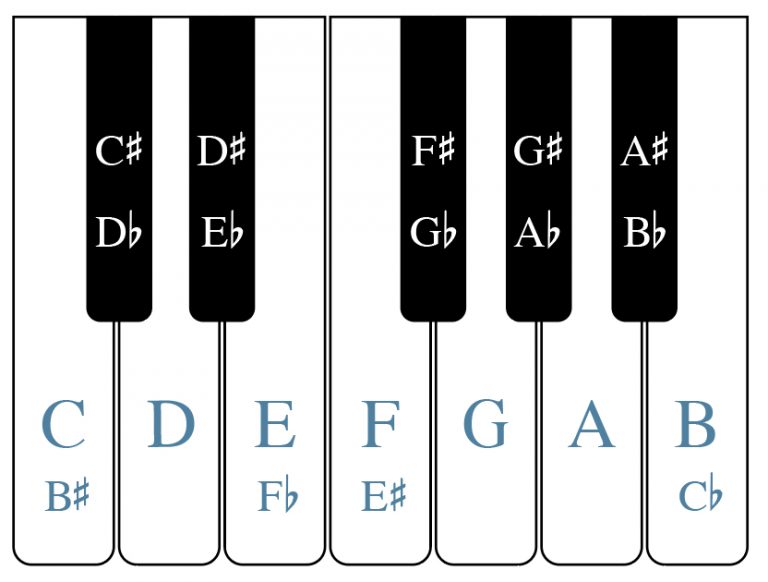

The musical ‘alphabet’ works the same way on the piano as on the notational staves. On the piano keyboard, there are a total of 88 keys. Unlike the diagrams above and below, on a real piano “A” is the very lowest note on the left side. If you start saying the musical alphabet there, you’ll notice that “A” falls in the middle of the set of three black keys every time. The same type of repetitive pattern is true of every note with the highest note on the piano being a C.

The black keys are the half steps. A sharp (♯) in front of a note tells you to play it up a step higher (the key to the right). You may also notice that the sharped note is not always a black key—there is no black key to the right of “E” or “B” so E♯ = F and B♯ – C. Flats (♭) merely are the opposite; they tell you to play a half step lower (one key to the left). You’ve got it—D♯ is the same note as E♭.

Major and Minor Scales

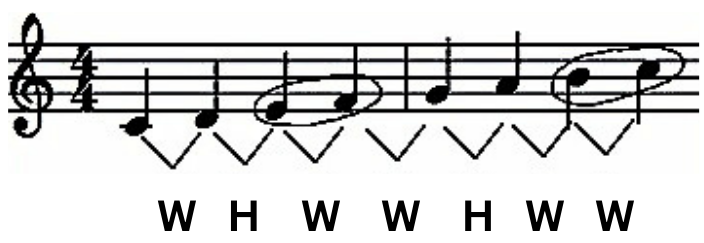

Scales are a basic component and the tonal basis of music. They are an organized series of seven distinct notes with a repeated note at the octave (diatonic) consisting of a pattern of half steps and whole steps. The most common and basic are the major and minor scales.

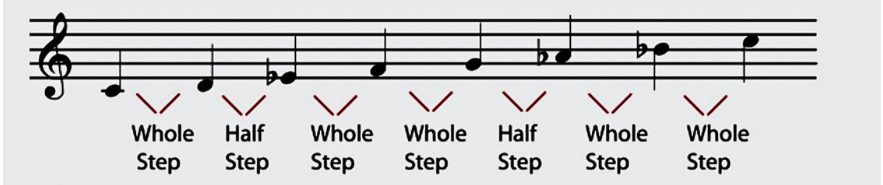

Major scales are some of the most commonly used musical scales. They are diatonic, meaning they include the seven ‘natural’ pitches arranged by five whole steps and two half steps for each octave. The sequence for a major scale is: whole, whole, half, whole, whole, whole, half. The most basic major scale to see as an example is the C Major scale.

A major scale can start on any note. If we start on D♭ instead of C, the pattern whole and half steps need to remain the same, so we must alter some notes. The same pattern of whole and half steps beginning on D♭ is: D♭ E♭ F G♭ Ab B♭ C D♭.

Natural minor scales are similar to Major scales in that they are diatonic with seven unique tones and a repeated octave and made up of patterns of half and whole steps, but the pattern is different. The sequence for a minor scale is:

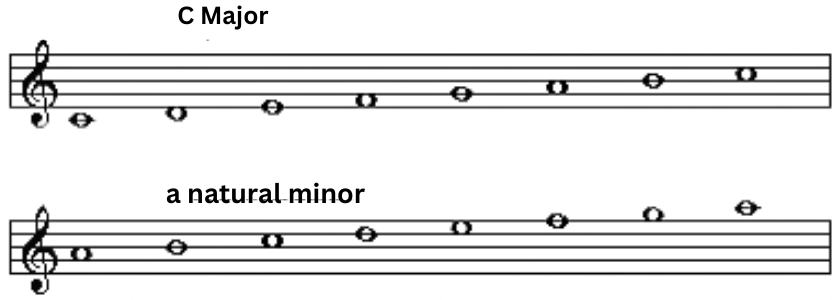

The most basic natural minor scale is the a natural minor scale which has no sharps or flats. Here are the C Major and a minor scales.

The most basic natural minor scale is the a natural minor scale which has no sharps or flats. Here are the C Major and a minor scales.

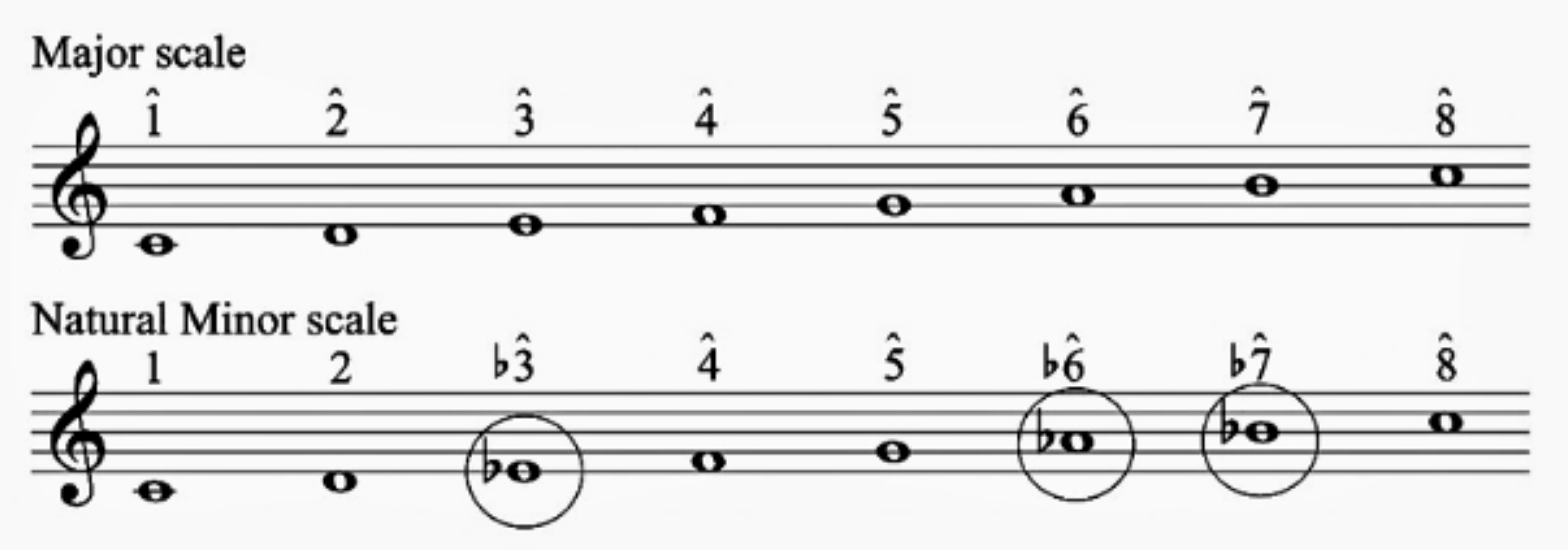

These two scales would be labeled as relative, meaning they have the same sharps and flats. C Major’s relative minor is a. There are also parallel minor scales which have the same starting note but different sharps and flats due to the patterns of whole and half steps. For example, C minor, would be the parallel minor of C major. The c minor scale = C D E♭ F G A♭ B♭ C. The natural minor scale can also be represented by the notation: 1 2 ♭3 4 5 ♭6 ♭7 8.

These two scales would be labeled as relative, meaning they have the same sharps and flats. C Major’s relative minor is a. There are also parallel minor scales which have the same starting note but different sharps and flats due to the patterns of whole and half steps. For example, C minor, would be the parallel minor of C major. The c minor scale = C D E♭ F G A♭ B♭ C. The natural minor scale can also be represented by the notation: 1 2 ♭3 4 5 ♭6 ♭7 8.

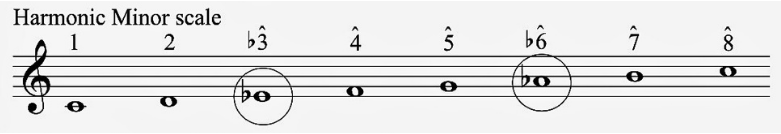

The harmonic minor scale is similar to the natural minor, except that the seventh degree is raised by one half step, making a larger interval (augmented 2nd) between the sixth and seventh scale degrees. The sequence for harmonic minor is whole, half, whole, whole, half, whole+half, half.

The harmonic minor scale is similar to the natural minor, except that the seventh degree is raised by one half step, making a larger interval (augmented 2nd) between the sixth and seventh scale degrees. The sequence for harmonic minor is whole, half, whole, whole, half, whole+half, half.

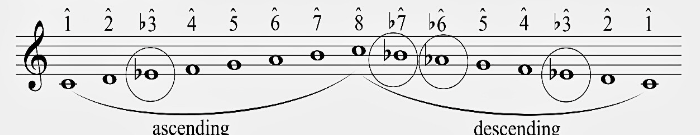

The melodic minor scale is the only scale that is different ascending and descending. Ascending it is similar to the Major scale except the melodic minor has a lowered 3rd scale degree. Descending, the melodic minor is the same as the natural minor. The sequence for ascending melodic minor is whole, half, whole, whole, whole, whole, half. The sequence for descending melodic minor is whole, whole, half, whole, whole, half, whole. The ascending melodic minor scale can be notated as: 1 2 ♭3 4 5 6 7 8, while the descending is: 8 ♭7 ♭6 5 4 ♭3 2 1.

The melodic minor scale is the only scale that is different ascending and descending. Ascending it is similar to the Major scale except the melodic minor has a lowered 3rd scale degree. Descending, the melodic minor is the same as the natural minor. The sequence for ascending melodic minor is whole, half, whole, whole, whole, whole, half. The sequence for descending melodic minor is whole, whole, half, whole, whole, half, whole. The ascending melodic minor scale can be notated as: 1 2 ♭3 4 5 6 7 8, while the descending is: 8 ♭7 ♭6 5 4 ♭3 2 1.

Key Signatures

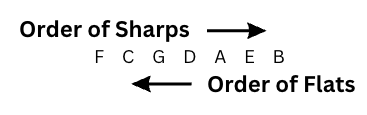

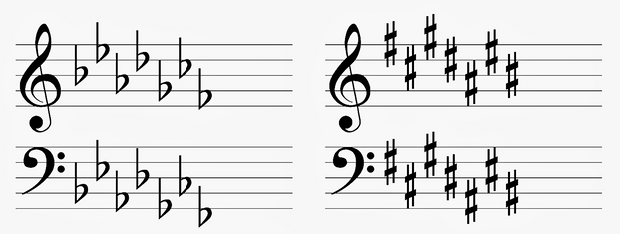

The sharps and flats placed at the beginning of a piece, between the clef and the time signature, is called the key signature. This indicates the tonal center or keynote/cornerstone of the piece. (Sometimes, you can cheat and just look at the first and last notes too.) The key signature is used so that every sharp or flat in the composition doesn’t have to be marked. The sharps or flats at the beginning of a piece always appear in the same order.

When you look at the key signature and you have one sharp at the beginning, it’s always going to be F♯. If you have two sharps, they will always be F♯ and C♯. These are five notes or an interval of a fifth apart. (Just count to five: FGABC).

When you look at the key signature and you have one sharp at the beginning, it’s always going to be F♯. If you have two sharps, they will always be F♯ and C♯. These are five notes or an interval of a fifth apart. (Just count to five: FGABC).

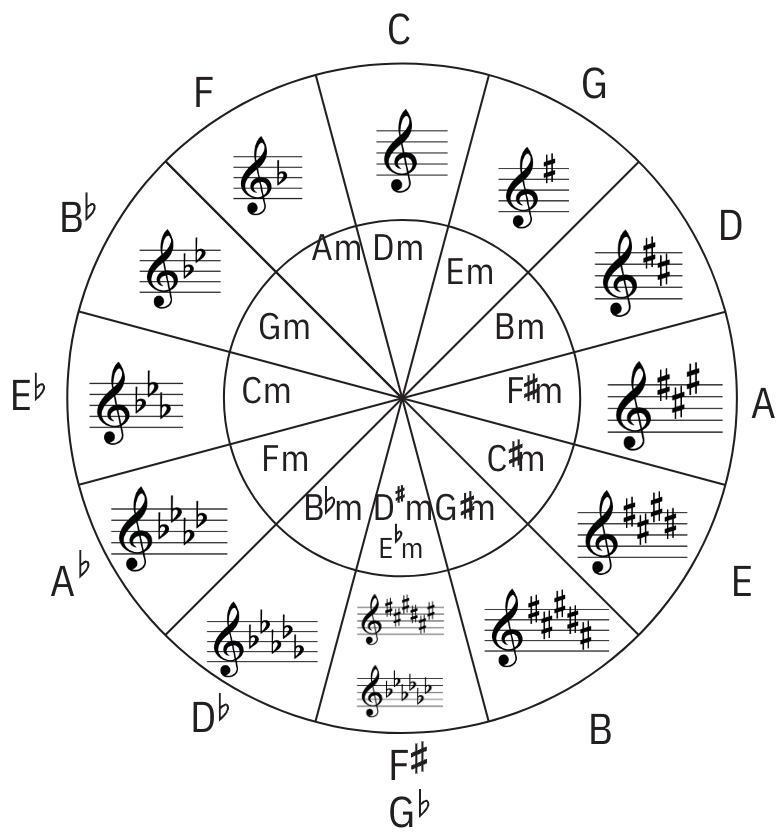

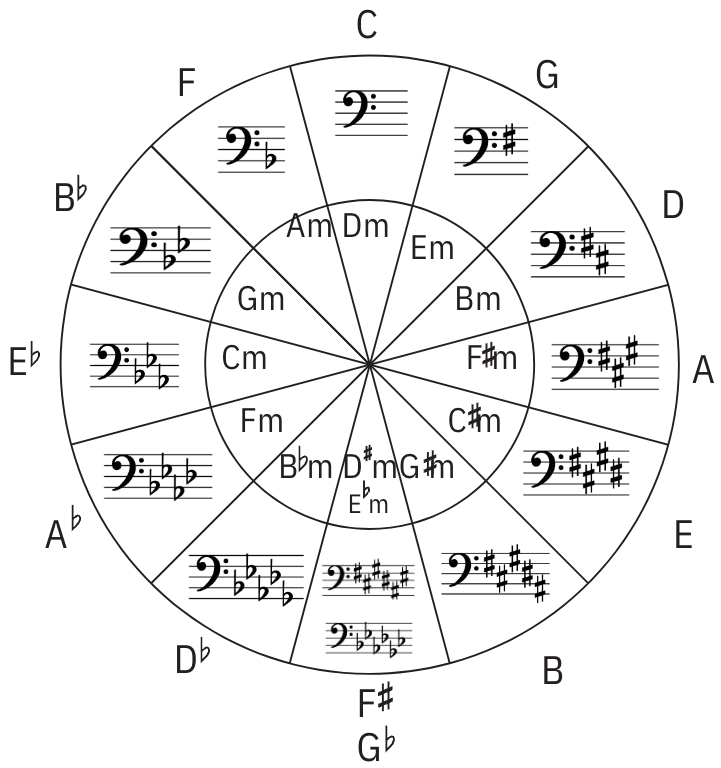

The interval of a fifth can also be used to help you identify and name key signatures. For example, the key of C Major has no flats or sharps. The key of G Major has one sharp (F♯). C to G is a fifth apart or five notes (CDEFG). The same applies to minor key signatures, a minor has no flats or sharps, and e minor has one sharp (F♯). When you lay these all out in a circle, it is called the Circle of Fifths and can be seen below.

If you can’t remember the major key from the sharps in the key signature, you can go up a half step from the last sharp in the key signature. For example: If there are 2 sharps in the key signature they would be F♯ and C♯ which would make it the key of D Major. (If you’re familiar with solfège, the last sharp is “ti” to the keynote “do.”) In minor, the key is one who step below the last sharp. For example, if you have 2 sharps, F♯ and C♯, they will be b minor.

Flats work a little differently. For Major keys, you move back one space on the Circle of Fifths or use the next to last flat. If you are familiar with solfège, the last flat to the right is “fa” to the keynote “do.” If you have three flats, they will always be B♭, E♭, and A♭, and you are in the key of E♭ Major. Another way to remember this is, if you begin on D♭ and play a major scale (WWHWWWH), you will have flatted BEAD and G in the process. For minor keys, there isn’t an easy shortcut other than memorization. The one method that will work is to look at the last flat and the key will be a Major third above this pitch. For example, if you have two flats, B♭ and E♭, you will be in the key of g minor. G is an interval of a Major 3rd above E♭—G,A,B♭.

Intervals

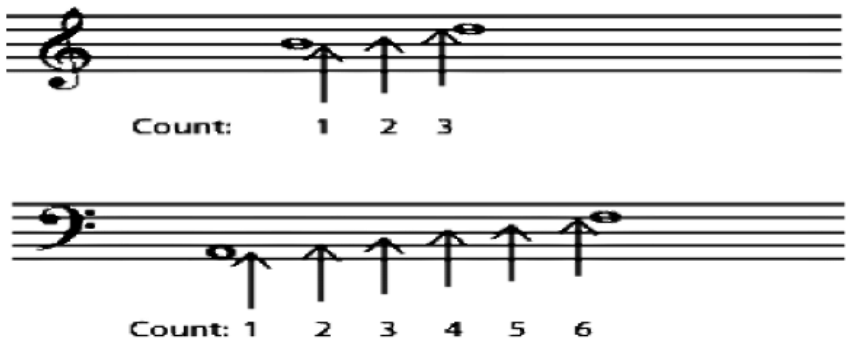

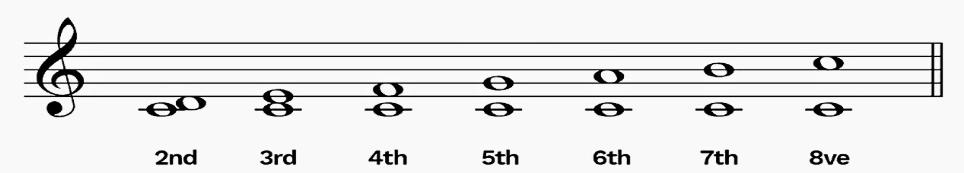

In music, an interval is the distance between two pitches. The first step in naming the interval is to find the distance between the notes as they are written on the staff. Start with the line or space the original notes is on, and then count every line and every space up to and including the second note. This gives you the number for the interval. The example in the treble clef example below is the interval from a B to D. To determine this, you simply count B, C, D—which is a third because there are three notes. The bass clef example below is an A to an F. You count, A, B, C, D, E, F—which is a sixth.

The smallest interval possible is a half-step. This is the next higher or lower note. For example, a half step above an A is an A♯; a half step below an A is an A♭. A half step above a B, is a C. A half step below a G♭, is an F.

A 2nd, is also known as a whole step (or two half steps).

An interval that has two of the same note is called a unison.

Identifying Interval Quality

We generally name the interval based upon its quality as well as its number. Intervals can be Perfect (P), minor (m), Major (M), Augmented, (A), or diminished (d). A major third (M3) is an interval name, in which the term major (M) describes the quality of the interval, and third (3) indicates its number. . An interval can be described as melodic if it refers to successively sounding pitches, or harmonic if the pitches are sounded simultaneously.

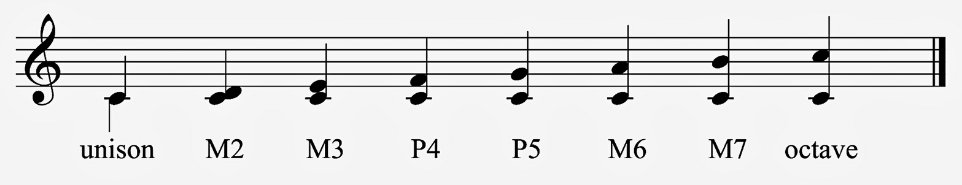

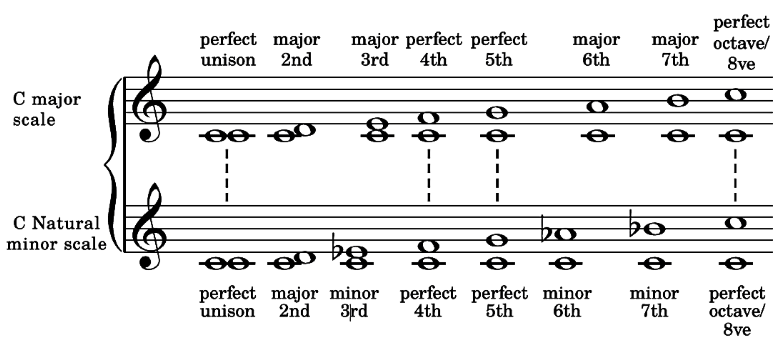

To look at the quality of intervals, we will begin by looking at the intervals within a major scale. Every note in a major scale is either a major or perfect interval (starting from the tonic pitch). Below are the intervals in a major scale.

To be a perfect interval the upper note has to be in the major scale of the lower note. There are three intervals that are considered Perfect (P) intervals:

- Perfect 4 (P4)

- Perfect 5 (P5)

- Perfect 8 (P8)—octave

There are four intervals that are called Major (M) intervals:

- Major 2nd (M2)

- Major 3rd (M3)

- Major 6th (M6)

- Major 7th (M7)

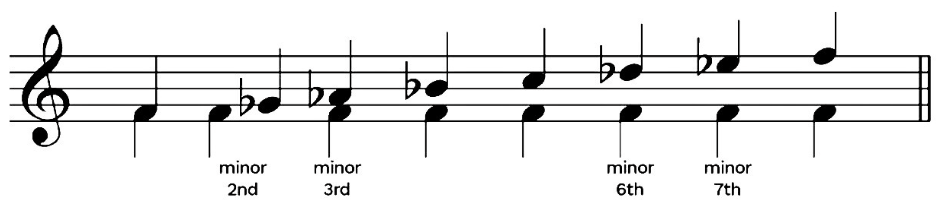

If we take the Major intervals and make each of them a half-step smaller, they become minor (m) intervals. Because there are four Major intervals, there are also four minor intervals.

- minor 2nd (m2)

- minor 3rd (m3)

- minor 6th (m6)

- minor 7th (m7)

Here is an example of minor intervals with an F Major scale but with the 2nd, 3rd, 6th, and 7th, lowered to minor intervals.

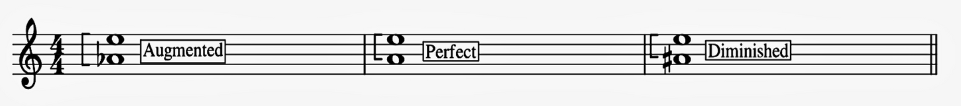

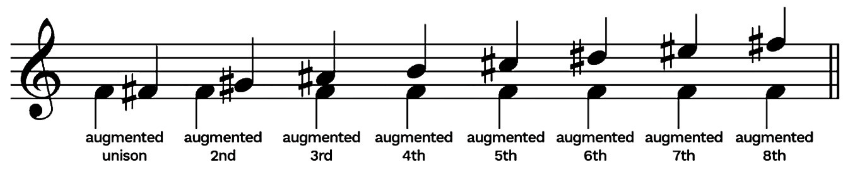

An Augmented (A) interval occurs when a Perfect or a Major interval is increased by a half-step, without changing the note name. The following example shows a M2 increased to an A2.

The following example shows the F Major scale with all Augmented (A) intervals.

As we saw previously, if we lower a Major interval by a half step, it becomes a minor interval. If we lower a minor (m) or Perfect (P) interval by a half-step, we get a diminished (dim) interval. Here are examples of each of these:

If we want to see these intervals applied to major and minor scales, here is an example. This is an example using C Major and c natural minor scales with intervals for each scale degree as well as the quality of the interval.

Next are a couple of resources to help you understand and remember the qualities of intervals.

Next are a couple of resources to help you understand and remember the qualities of intervals.

Example 1:

| Interval Name | Abbrev | ½ steps | Example |

| Perfect Unison | PU | 0 | C – C |

| minor second | m2 | 1 | C – D♭ |

| Major second | M2 | 2 | C – D |

| Augmented second | A2 | 3 | C – D♯ |

| Diminished third | dim3 | 2 | C – E♭♭ |

| minor third | m3 | 3 | C – E♭ |

| Major third | M3 | 4 | C – E |

| Augmented third | A3 | 5 | C – E♯ |

| Diminished fourth | dim4 | 4 | C – F♭ |

| Perfect fourth | P4 | 5 | C – F |

| Augmented fourth (tritone) | A4 | 6 | C – F♯ |

| Diminished fifth (tritone) | dim5 | 6 | C – G♭ |

| Perfect fifth | P5 | 7 | C – G |

| Augmented fifth | A5 | 8 | C – G♯ |

| diminished sixth | dim6 | 7 | C – A♭♭ |

| minor sixth | m6 | 8 | C – A♭ |

| Major sixth | M6 | 9 | C – A |

| Augmented sixth | A6 | 10 | C – A♯ |

| diminished seventh | dim7 | 9 | C – B♭♭ |

| minor seventh | m7 | 10 | C – B♭ |

| Major seventh | M7 | 11 | C – B |

| Augmented seventh | A7 | 12 | C – B♯ |

| diminished octave | dim8 | 11 | C – C♭ |

| Perfect Octave | P8 | 12 | C – C |

If you are comfortable with solfège, this may be another method for you to make sense of, and remember, intervals.

Triads

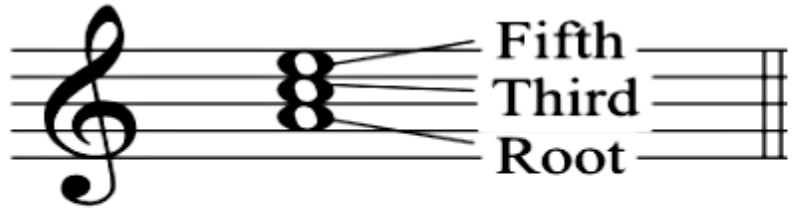

A triad is a chord constructed with three notes. The three notes are stacked on top of one another in consecutive thirds. Triads are a basic chord structure and the basis of how other types of chords are constructed. When the three notes are stacked, the lowest note is called the root, with the other two referred to as the third and fifth, which corresponds to their scale degree. For this example, the root is A, the third is C, and the fifth is E.

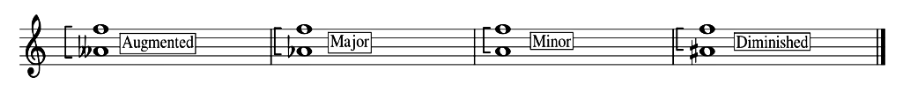

There are four kinds in triads we will discuss:

- Major

- Minor

- Augmented

- Diminished

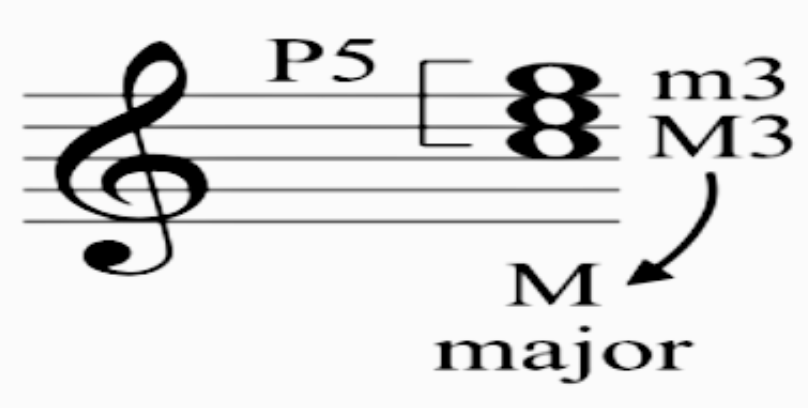

The Major triad consists of a Major 3rd between the root and the third, and then a minor third between the third and fifth, with a Perfect 5th between the root and the fifth.

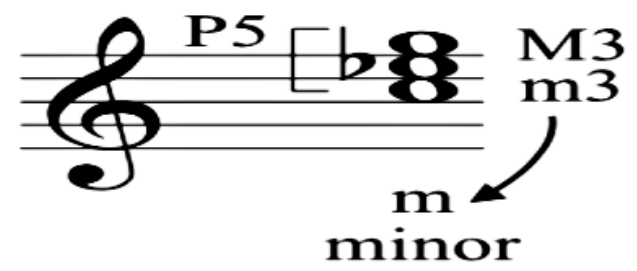

The minor triad consists of a minor 3rd between the root and the third, and then a Major third between the third and fifth, with a Perfect 5th between the root and the fifth.

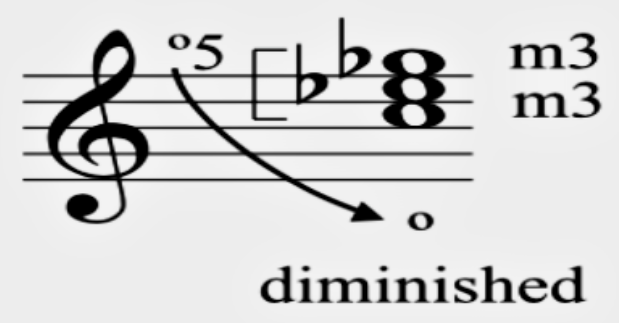

The diminished triad consists of a minor 3rd between the root and the third, and then another minor third between the third and fifth, with a diminished 5th between the root and the fifth.

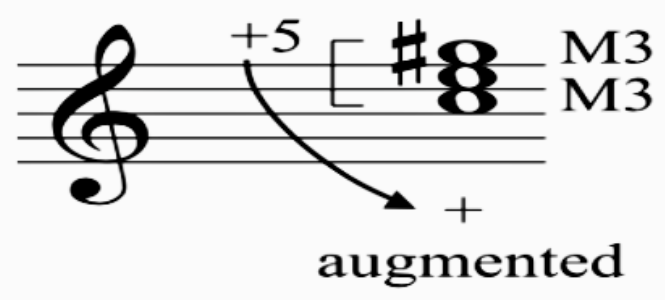

The augmented triad consists of a Major 3rd between the root and the third, and then another Major third between the third and fifth, with an augmented 5th between the root and the fifth.

Triad Inversions

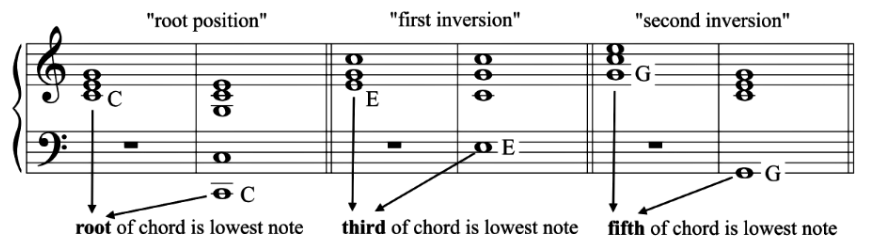

An inverted triad still contains the same pitches but does not have the root as the lowest note. A triad in root position has the root as the lowest note, first inversion is when the third of the chord is the lowest note, and second inversion is when the fifth is the lowest note. Here is a diagram showing the three triad positions

Additional Resources

Holm-Hudson, Kevin. (2016). Music Theory Remixed: A Blended Approach for the Practicing Musician. Oxford University Press.

Kostka, Stefan and Byron Almén. (2024). Tonal Harmony (9th edition). McGraw-Hill Education.

Laitz, Steven G. and Michael R. Callahan. (2011). The Complete Musician: An Integrated Approach to Theory, Analysis, and Listening (5th edition). Oxford University Press.