8.0 Biosecurity for Aquatic Livestock Production

8.5 Animals

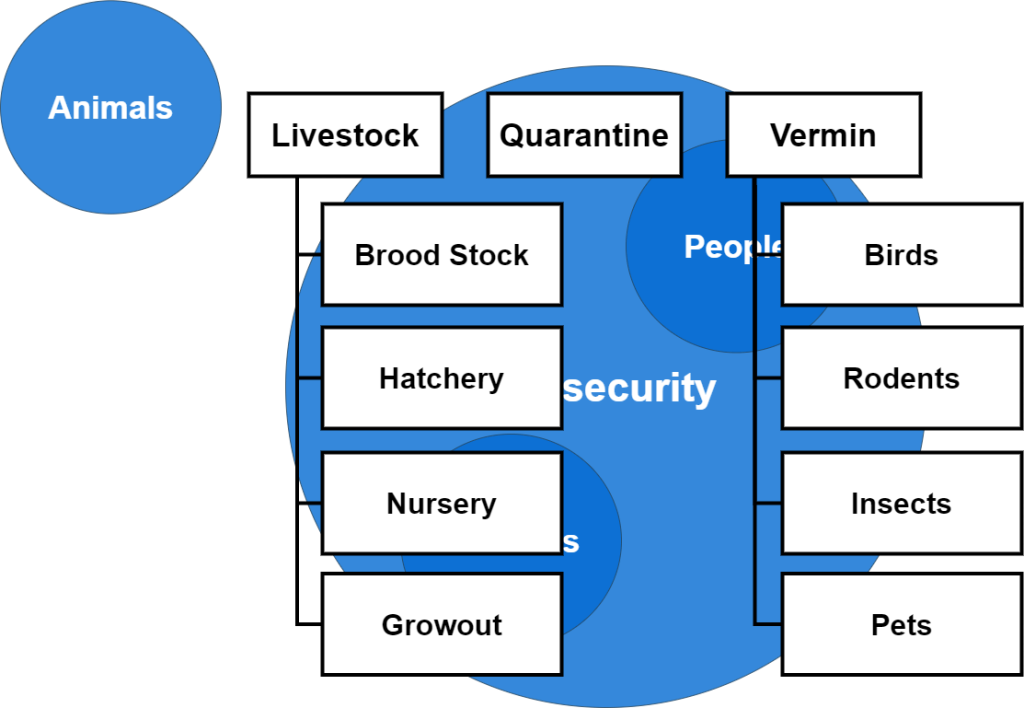

Livestock production aspires to rear only the profitable species for the organization. Biosecurity strategies have been developed and successfully used in other livestock industries. Similar strategies appear in aquatic livestock production operations, as shown in Figure 8.09.

Separating and isolating livestock on the basis of life stages is a fundamental tool in implementing a BP. This isolation and separation can be useful to prevent some pathogens from spreading throughout the operations. If the young are more susceptible to a pathogen, isolate younger animals as soon as possible from the valuable broodstock that may also be susceptible to the pathogen once it is incubating in nonseparated immature individuals. In addition to the reduction of pathogen spread through separating livestock by life stage, there are other benefits of this practice. Broodstock fish are the older, larger, more mature individuals. For fish, the larger the broodstock, the greater the fecundity (gamete numbers produced). Offspring numbers are important variables for production costs and profits. The facility has a minimum set cost of existence and operation, and the more offspring that can be successfully produced and harvested for the same space, electricity, and heat, the larger the profit margin potential.

Controlling Animal Spaces

Quarantine facilities are provided for newly purchased livestock and separate from production areas. Hatcheries are or can be designated in this type of the area to permit monitoring larvae for pathogens coming in through eggs. This isolated facility assures no direct or indirect physical connection with the animals in production. Separate water, personnel, workflow, room, and equipment are required to get the full benefit from quarantine processes. Time in quarantine is important. The length of time will depend on the incubation time of known and economically important pathogens or parasites. Quarantine periods must be long enough to accommodate testing assay times so that results are available before the animals are moved to production but not so long that the quarantine period becomes economically impractical. The testing protocols may be repeated to assure negative results in subsequent tests. Quarantine facilities must be properly sized to follow an all-in-all-out process. Each batch or lot of incoming fish must be placed in separate quarantine facilities. Simultaneous habitation that permits use of the same room, equipment, water, and personnel is a biosecurity failure.

From a biosecurity viewpoint, if livestock and pathogens or pests never occur in the same place simultaneously, there is no disease. Pathogens have many skills of survival, including biofilms and inactive states. Removing livestock, draining the tanks, and plumbing do not guarantee that the pathogen is gone. Some method of cleaning is required to remove biofilm and inactivate microbes. Disinfection is then used to kill any exposed (nonbiofilm) organisms.

Limiting Vermin

Vermin are extraneous and unwanted animals that are kept away and separated from livestock production. The list in Figure 8.9 can predict the types of vermin prevention measures. Operational factors such as waste feed or easily accessible feed containers are an attractant to birds, rodents, insects, and even wandering pets. Harborages are generally abundant for vermin in aquatic livestock facilities. Open doors permit vermin to escape weather events and predators. If undisturbed or inaccessible, nesting will occur, resulting in more vermin. The slightest openings or crevices can give access to vermin. They may enter at a small size and then grow, leaving the question of how the larger animal had entered, as the inspection did not find the smaller version of the large animal.

The problem with many vermin is the ability to carry and shed deadly pathogens on livestock. Simply nibbling on feed in the sack or cart will generally leave urine and feces in the feed. Rodents follow routine paths through a facility that may not be noticed unless personnel intentionally look for them. Trained personnel can be used to identify these routes and eliminate the rodents using them.

Do not permit birds to enter through ventilation intakes or exhausts. Screens and vent design prevent birds from exploring the building interior for roosting, feed, and nesting locations. Birds are not discreet in elimination tasks. Droppings (feces or urine) can easily fall into production tanks or open biofilters if perches are positioned overhead. Invading birds use lighting fixtures and feed distribution tubes as perch structures. Careful building design with screened eves and overhangs is necessary. Damaged structures that open overhead spaces may be routes for birds, insects, and rodents to enter the facility and work undetected to enter production areas.

Vermin-Control Animals

Caution should be used regarding guard animals to control vermin. Loose animals within perimeter fencing are not optimal because the free-moving animal may find its way into production or support areas. Feces, urine, and even physical damage may cause an attraction for the vermin that is not eliminated. Supervised vermin-control animals are effective and must be closely controlled to ensure biosecurity is maintained.

Vermin-control animals bring to mind the idea of pet animals having access to the facilities. The area inside the perimeter must be animal-free to prevent the connection between livestock and pathogens. Bait boxes along foundations will work for many rodents. Perimeter fences can create havens for small animals. Fences can have openings that are small enough for animals to enter but prevent predation by larger animals. Birds can be controlled with repellents such as noise canons and by interfering with their flight through suspended nets or lines. Some birds will leave if lights are flashed, and do not find refuge where all interior and exterior resting and roosting ledges are eliminated. Insects such as flies are attracted by uncovered garbage, spoiling feed, or dead fish and can be managed with timely removal of attractants after discovery. Pets are not welcome at a biosecure facility. Any support animals must be strictly designated to certain areas and not be allowed to mingle with production personnel on break or meal times.

Dust and Debris

While most readers would not see dust and windblown debris as vermin, there are recorded situations where parasites can be windblown into the production area and settle into the water. One such wind-borne parasite is Amyloodinium. This parasite can be found in surf mist and carried for miles before settling. Prevention of such parasites entails choosing a building site away from coasts and using filtration on intake air sources to eliminate dust from the facility. Knowing neighbors’ activities can also help determine the filtration level necessary.

When animals are properly provided for as livestock and vermin are eliminated, the associated risks can be monitored and records kept documenting the success. This reduction in risk to biosecurity then appears in the biosecurity diagram as depicted in Figure 8.10.

In one facility, the surrounding neighborhood used open fires for garbage disposal. The risk from garbage fire pollutants was regarded as a hazard to the atmosphere and water management inside the facility. The risk was analyzed, and the cheaper solution was to provide garbage pickup for the neighborhood than put high-efficiency filtration on the facility’s intake vents. As a footnote to this risk analysis decision, the facility was high enough in livestock density and required large air exchanges to vent the carbon dioxide generated from the biofilter. High atmospheric CO2 buildup in the production hall hindered off-gassing the CO2 from the production water.