Level 2

Fair Use

In this module you will explore how you can use copyrighted materials using the fair use doctrine. In this part of the copyright law, students and teachers (as well as other groups) have special permission to use media and other works.

I want to use a copyrighted image in a presentation, classroom, or other learning activity that doesn’t fall under the public domain or doesn’t have a creative commons license. What should I do?

Learn about fair use! Section 107 of the copyright code (i.e., fair use) allows students and teachers to use copyrighted materials without permission. There are two interpretations of fair use: (1) the four factors from the original law and (2) transformative use. This module will focus on the four factors.

Wait, what is fair use again?

Fair use (17 U.S.C. §107 helps BALANCE the rights of copyright owners with copyright users. Because of fair use, certain kinds of uses are allowed, without permission or payment—in fact, even in the face of an explicit denial of permission—at any point during the copyright term. Fair use is why things like quoting a book in order to review it, or publicly displaying a reproduction of an artwork in order to critique it, are legal.

Fair use is an important part of copyright law that provides some flexibility for users and new creators. At its core, fair use ensures that there are some kinds of uses that do not require permission or payment. But there are no easy rules for fair use—if you want to take advantage of its flexibility, you have to understand its complexities!

Each possible use of an existing work must be looked at in detail and the law spells out several factors that determine whether a use is fair. No one factor is decisive – you always have to consider all of them, and some additional questions. Even after considering all relevant issues, the result is usually in impression that a particular use is “likely to be fair” or “not likely to be fair.” There are rarely definitive answers outside of courts.

1. Purpose and Character of Use

This is the only factor that deals with the proposed use—all the others deal with the work being used, the source work. Purposes that favor fair use include education, scholarship, research, and news reporting, as well as criticism and commentary more generally. Non-profit purposes also favor fair use (especially when coupled with one of the other favored purposes.) Commercial or for-profit purposes weigh against fair use—which leaves for-profit educational users in a confusing spot!

2. Nature of the Original Work

One element of this factor is whether the work is published or not. It is less likely to be fair to use elements of an unpublished work—which makes sense, basically: making someone else’s work public when they chose not to is not very fair, even in the schoolyard sense. Nevertheless, it is possible for use of unpublished materials to be legally fair.

Another element of this factor is whether the work is more “factual” or more “creative”: borrowing from a factual work is more likely to be fair than borrowing from a creative work. This is related to the fact that copyright does not protect facts and data.With some types of works, this factor is relatively easy to assess: a textbook is usually more factual than a novel. For other works, it can be quite confusing: is a documentary film “factual”, or “creative”—or both?

Uses from factual sources are more likely to be fair than uses from creative ones —though not every source is easily classified!

3. Amount and Substantiality of the Portion Used

Amount: this is an element that many guidelines give bad advice about. A use is usually more in favor of fair use if it uses a smaller amount of the source work, and usually more likely to weigh against fair use if it uses a larger amount. But the amount is proportional! So a quote of 250 words from a 300-word poem might be less fair than a quote of 250 words from a many-thousand-word article. Because the other factors also all come into play, sometimes you can legitimately use almost all (or even all) of a source work, and still be making a fair use. But less is always more likely to be fair.

Substantiality: this element asks, fundamentally, whether you are using something from the “heart” of the work (less fair), or whether what you are borrowing is more peripheral (and more fair). It’s fairly easily understood in some contexts: borrowing the melodic “hook” of a song is borrowing the “heart”—even if it’s a small part of the song. In many contexts, however, it can be much less clear.

4. Effect of the Use on the Potential Market

This factor is truly challenging—it asks users to become amateur economists, analyzing existing and potential future markets for a work, and predicting the effect a proposed use will have on those markets. But it can be thought of more simply: is the use in question substituting for a sale the source’s owner would otherwise make—either to the person making the proposed use, or to others? Generally speaking, where markets exist or are actually developing, courts tend to favor them quite a bit. Nevertheless, it is possible for a use to be fair even when it causes market harm.

Napster was a pioneering file sharing program where users could get music for free, but is violated copyright and this area of fair use. Watch this documentary to hear the full story!

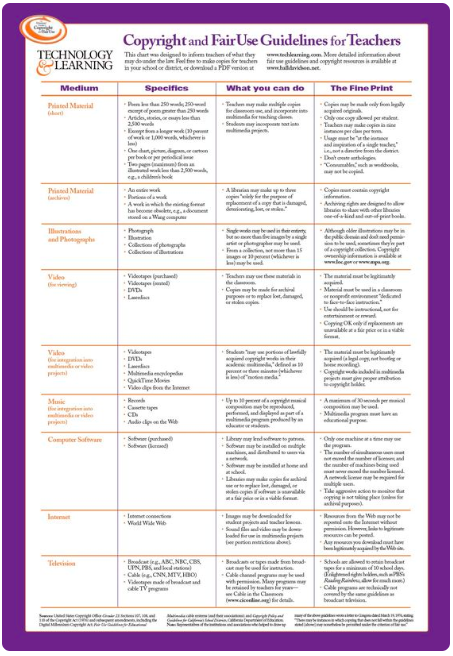

What about those educational guideline posters?

It’s tempting to try to use the categories listed in the statute (“criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching […], scholarship, or research”) as hard-and-fast rules. However, the key words in that paragraph are “for purposes such as…”—the list is illustrative, not exhaustive. There are both fair and unfair uses within those categories, and many fair uses outside of them, too.

It’s also tempting to look for guidance from sources that give hard-and-fast rules. Some ideas people have about clear-cut fair uses (“all educational uses are okay!” “the first time I share an article with my students, it’s always allowed”) come from agreements developed between a few players, or as a result of settlements of lawsuits. Many of these ideas are out of date—the agreements may have expired, or some of the players may have decided not to play by those rules anymore. None of these ideas have legal force!

Another set of misleading hard-and-fast fair use educational guidelines come from the content industry—often developed as guidelines to assess risk internally—but then incorrectly shared, or misunderstood, as statements of law: “quoting 250 words or less is always okay”, “any video clips over 30 seconds are not fair use”. “Amount” is measured proportionately for fair use purposes, so these types of guidelines are always misleading. 25 seconds from a work that totals 35 seconds could well be unfair, and 5 minutes from a 2-hour film might be fair. Taking “substantiality” into account, even 3 seconds of the “heart” of a short video could be unfair! Hard-and-fast “amount” guidelines are not legally binding, and can lead you to think something is fair when it is not, and to think something is not fair when in fact it is!