Module 1: In the Field

Perform biodiversity research through making and translating your observations of the natural world into research questions, hypotheses, and experimental design that are grounded in scientific literature.

Fieldwork Basics

Course-based fieldwork has been shown to be associated with increases in student success and retention.[1] A successful field experience depends on proper preparation. One of the most important ways to prepare for the field is through dressing appropriately. As fieldwork occurs outdoors, all kinds of weather and environmental conditions can be experienced. It is important for our safety and our comfort that we dress to meet these conditions.

Generally long pants and sturdy shoes are essential. Long sleeves are often a good idea, but can somewhat depend on preference. If they are required, you will be informed ahead of time. It is important we consider the fit and type of fabrics we are wearing as we may be more comfortable in some than in others – comfort is more important than fashion as being comfortable will help us put our focus on the experience rather than our level of discomfort. Additional considerations are a hat, sunscreen, and bug spray. If it is raining but not storming we will most likely go outside so be sure to wear something rainproof. If you have any issues acquiring appropriate gear, please contact the instructor ahead of time and they will work to help find a solution. No one’s field experience should be limited by access to appropriate gear. It is also essential to always bring water. A snack may be nice as well, but that is personal preference.

Classes of Field Trips

Note to instructors: This course implements several classes of field trips throughout the semester to expose students to a variety of biodiversity research settings and biodiversity researchers. Be sure to ask the researchers you partner with to give a short, personal bio at the beginning of each field trip, so that students can find points of connection with them. It is especially beneficial for them to share their path as a scientist, so that students can see there are many ways forward.

Data Field Trips

For data field trips, we will join a biodiversity scientist from our institution in the field to do some hands-on data collection and analysis. These field trips take part over at least two weeks. Week 1 involves data collection in the field while week 2 involves learning how to analyze the data we have collected.

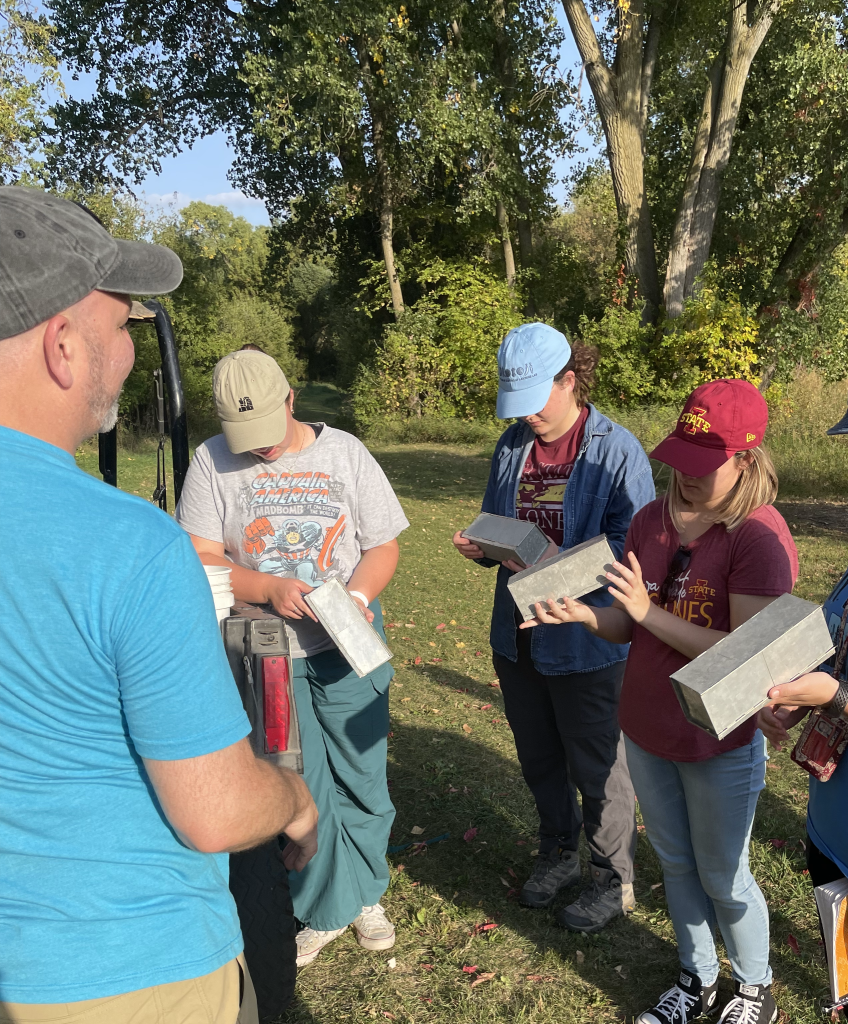

Example 1: Herbaria Specimens

Week 1: This field trip will cover rationale for collecting plant specimens, specimen collection ethics, how to collect and press plants and/or plant parts, gathering relevant information for specimen label generation, and drying plant samples. We will select and press plant specimens in the field.

Week 2: In this field trip we will learn how to mount the plant specimens collected the previous week. Additionally, we will receive an introduction to the Ada Hayden Herbarium and learn about the history, diversity, and importance of herbaria. We will also learn about how research is conducted in herbaria, what kinds of questions herbaria are ideal for helping us answer, and how specimens can be used in research.

Example Make-up Assignment

In order to make up for the missing field trip to the Herbarium, please watch videos 1–3 and 7 on the Ada Hayden Herbarium website to learn more about the Herbarium. After watching the videos, write about what you learned as an entry in your field notebook.

Additionally, please make your own herbarium specimen. Use the specimen sheets provided here as a guide for how the specimen should be constructed. However, since you will not have actual plants, please make a drawing of the species of your choice that clearly illustrates the plant’s features. In addition to the drawing, please create a label for your specimen that includes at minimum: species name and common names, detailed location of where it was collected (hypothetical), name of collector (you), and date of collection.

Reading Paired Field Trips

For reading field trips, we will pair up with a biodiversity scientist from our institution that has a local field site about which they have ideally published papers. We will learn that field research is happening in our own backyard and leading to genuine scientific contributions. It also presents an excellent opportunity to practice reading scientific literature – with the added benefit of a real life connection to the scientist who published it. Consequently, assigned papers should be read before going on the field trip so questions can be asked of the scientist and discussions of the paper can take place at the field site. See the Appendix 5 for a guide to help direct reading of a scientific paper.

Example 1: Prairie Restoration

Visit the Iowa State Central Ag Farms to learn about the role of wetlands in remediating nutrient runoff and experiments testing the role of seed mixes on restoring ecosystem services.[2]

Example 2: Temperature and Hormones in Turtles

Visit the Iowa State Horticulture Farm to learn about experiments on the effects of temperature on circulating hormones in female painted turtles.[3]

Example 3: Ancient Maize DNA

Visit a maize diversity domestication demo plot and learn about ancient DNA research in maize and what it can teach us about maize domestication and historic human societal dynamics.[4]

Overnight Field Trips

An overnight field trip will help to build connection and increase a sense of belonging in the biodiversity sciences. Additional faculty members will join the trip to provide opportunities to build professional connections in a more informal setting. Visiting a field station provides opportunities for numerous field site visits and a more intensive field experience. Invited faculty with field expertise can also demo hands-on field work (e.g., live mammal trapping) to give a taste of field research.

Example 1:

Visit a field station such as Lakeside Laboratory for a weekend to fit in numerous field experiences and networking opportunities (See Appendix 2 for the trip itinerary).

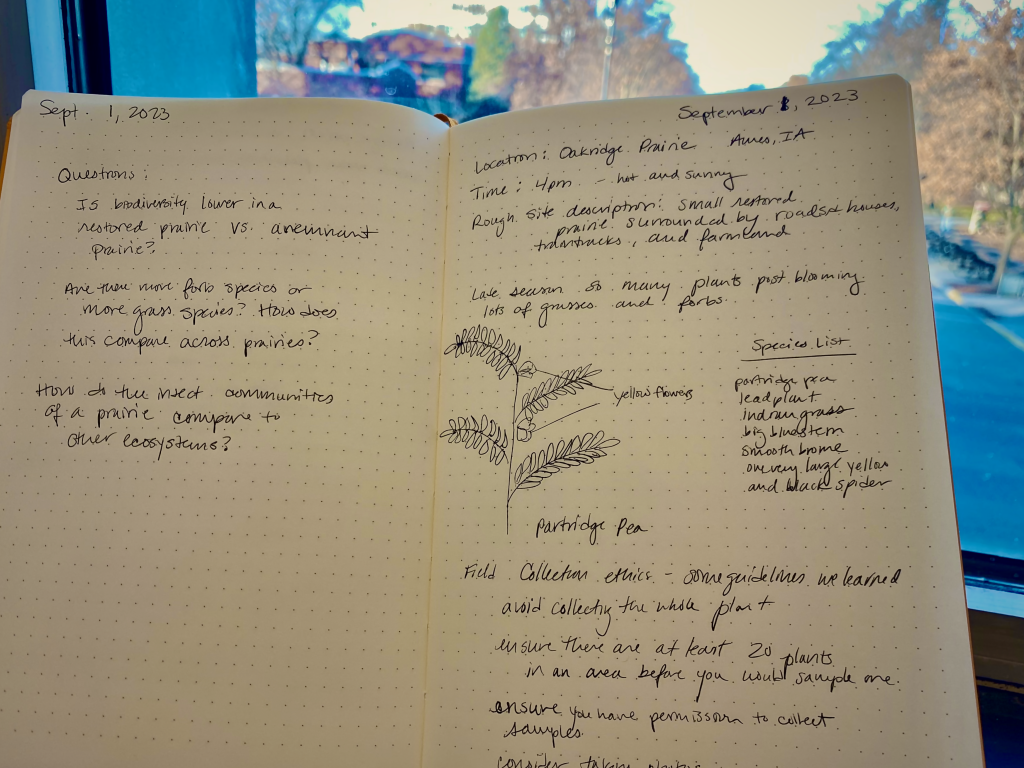

Field Notebook

During this course we will be generating a personal field notebook. Field notebooks are an essential tool scientists utilize to document their observations and their thinking.Nicotra, AB, et al. 2022. An innovative approach to using an intensive field course to build scientific and professional skills. Ecology and Evolution. 12:e9446. DOI: 10.1002/ece3.9446.[\footnote] In this course the field notebook should be utilized for the following situations.

- Observations made during each field trip.

- Questions and hypotheses generated from field trip observations.

- Reflective writing exercises (periodic and assigned)

- Notes you take in class.

- Notes you take based on readings and discussions of the scientific literature.

All content should be dated, and pages numbered. Field trip observations should include location information. Each entry type should be started on a fresh page and have a header describing the contents. This will help things stay somewhat organized throughout the semester. Set aside several pages at the beginning of the field notebook to build an index. This will help in quickly finding information in the future. Beyond this, feel free to be creative with the field notebook. Sketches, poems, or add additional content beyond what is outlined here are all encouraged. Field notebooks will be peer reviewed twice during the semester to provide constructive feedback on their content. This will help develop field recording skills and encourage the consideration of additional approaches to take with the field notebook. In addition, field notebooks will also be reviewed and assessed by the instructor near the end of the semester.

Check out this resource from the American Museum of Natural History on keeping field journals:

Reflection

Reflection is an important component of this course module. This allows us to practice skills of reflection which will serve us well both personally and professionally. For the field module, this comes through the form of reflective writing exercises. Three reflective writing exercise are assigned throughout the semester. The first two are informal and are included in the field notebook. The third comes at the end of the semester and asks you to consider your whole experience of the course. The third reflection must be typed and submitted as a separate assignment.

Field Notebook Reflective Writing

Complete a reflective writing entry in your field notebook. These assignments serve to promote meta-cognition of all you have been learning about during the semester. Thus when initiating these assignments, spend some time flipping through your previous observations. See if you find any common themes in what you have been looking at – it is possible, but not required for these assignments to help you start to think about potential research proposals. You are also welcome to use them as an opportunity to consider how what you learn in this class relates to other classes or areas of your life. Their purpose is to be reflective – they do not have any particular requirements, other than that you practice reflective thinking (a highly useful life skill, if anything). They should take several pages of your notebook (depending on page dimension). There is no particular length requirement, but a reflection of about 500 words should be sufficient to achieve the assignment’s purpose – but if you feel like writing more, please do not hesitate to do so. To be effective, these need to be completed by the due date, but they will be assessed for completion upon final submission of the field notebook.

Final Reflective Writing

The final reflective writing assignment is a bit more formal. Here you should consider the course as a whole. You may wish to write about what you have learned, what you have been surprised by, elements of the course you found impactful, etc. These are suggestions; what you include in the reflection is ultimately up to you. Your reflection should be typed and submitted by the due date rather than entered into your field notebook, and should be approximately one typed page in length.

Formatting: 1 inch margins, 12 point Calibri font, and double spaced. Your first and last name should be placed in the header of the document, not in the main body. All assignments should be submitted as .docx or .pdf file types. Files should be named thoughtfully and intentionally e.g., Lastname_PeerReview1.docx

- Beltran, RS et al. 2020. Field courses narrow demographic achievement gaps in ecology and evolutionary biology. Ecology and Evolution. 10(12):1-13. ↵

- Meissen, JC et al. 2020. Seed mix design and first year management influence multifunctionality and cost-effectiveness in prairie reconstruction. Restoration Ecology. 28(4):807-816. ↵

- Topping, NE and Valenzuela N. 2023. Thermal response of circulating estrogens in an emydid turtle, Chrysemys picta, and the challenges of climate change. Diversity. 15(3):428. ↵

- Kistler, L et al. 2020. Archaeological Central American maize genomes suggest ancient gene flow from South America. PNAS. 117(52):33124-33129. ↵