Topic 4. Perception

The Perceptual Process

Perception is how you interpret the world around you and make sense of it in your brain. You do so via stimuli that affect your different senses — sight, hearing, touch, smell, and taste. How you combine these senses also makes a difference. For example, in one study, consumers were blindfolded and asked to drink a new brand of clear beer. Most of them said the product tasted like regular beer. However, when the blindfolds came off and they drank the beer, many of them described it as “watery” tasting (Ries, 2009). This suggests that consumers’ visual interpretation alone can influence their overall attitude towards a product or brand.

![Niosi, A. (2021). The Perceptual Process: Sensation & Perception. [Image]. Licensed under CC-BY-NC-SA. Graphic depicting sensory receptors processing environmental stimuli and further processing stimuli through Exposure, Attention, Interpretation, and eventually Adaptation.](https://iastate.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/94/2019/01/Perceptual-Process-4-1024x576.png)

The Perceptual Process

Perception is the process of selecting, organizing, and interpreting information. This process includes the perception of select stimuli that pass through our perceptual filters, are organized into our existing structures and patterns, and are then interpreted based on previous experiences. Although perception is a largely cognitive and psychological process, how we perceive the people and objects around us affects our communication. We respond differently to an object or person that we perceive favorably than we do to something we find unfavorable. But how do we filter through the mass amounts of incoming information, organize it, and make meaning from what makes it through our perceptual filters and into our social realities?

Ultimately, the perceptual process develops a consumer’s perception of a brand and formulates the brand’s position vis-à-vis the competition on what marketers call a positioning strategy.

If consumers were to only rely on sensation, it is unlikely they would be able to draw any distinction between similar products. Peanut butter, cola, ice cream…each of these product categories have competitors vying to differentiate their products from one another. If you were to organize blind taste-tests with your friends where they could only rely on the sensation of taste, they may not be able to distinguish between them. So while sensation is what we experience when our sensory receptors are engaged, it is perception, that ultimately influences our consumer decisions and forms the basis of our preferences.

For marketers, having your brand stand out in a crowded and noisy marketplace is critical to success: playing to consumers’ senses is “next level” marketing as these rich experiences can code a brand into the consumer’s memory. Capturing the consumer’s attention through stunning visual appeals, catchy sounds, tasty samples, delicious aromas and hands-on experiences (also known as Guerilla Marketing) have completely over-taken the passive advertisements and billboards of the past. When done successfully, sensory marketing transitions a brand from “barely being noticed” to earning a top position in the consumer’s mind.

Exposure

We take in information through all five of our senses, but our perceptual field (the world around us) includes so many stimuli that it is impossible for our brains to process and make sense of it all.

Consumers are bombarded with messages on television, radio, magazines, the Internet, and even bathroom walls. The average consumer is exposed to about three thousand advertisements per day (Lasn, 1999). Consumers are online, watching television, and checking their phones simultaneously. Some, but not all, information makes it into our brains. Selecting information we see or hear (e.g., Instagram ads or YouTube videos) is called selective exposure.

Exposure speaks to the vast amount of commercial information—media messages, commercial, and other forms of advertisements—we are constantly subjected to on a daily basis.

In 2017, Forbes.com contributing writer Jon Simpson challenged readers to count how many brands they are exposed to from the moment they awake. From the bed to the shower to the breakfast table, how many brands have you already come in contact with? 10? 20? Then turn on your phone and start scrolling through your Twitter news feed…and now Instagram. Before you leave for work or school, the number of brands you’ve been exposed to likely climbs into the hundreds. Simpson claims that, “[d]igital marketing experts estimate that most Americans are exposed to around 1,000-4,000 ads each day” (Simpson, 2017).

Given this sea of images, sounds, and messages, how can we possibly make sense of any one brand’s message? Consumers will devote a degree of mental processing to only those messages that relate to their needs, wants, preferences, and attitudes. Brands are banking on the fact that with higher degrees of exposure, at some point their message is going to “stick” and capture consumers’ attention at just the right moment.

The absolute threshold of a sensation is defined as the intensity of a stimulus that allows an organism to just barely detect it. The absolute threshold explains why you don’t smell the cologne someone is wearing in a classroom unless they are somewhat close to you.

The differential threshold (or just noticeable difference, also referred to as “JND”), refers to the change in a stimulus that can just barely be detected. In other words, it is the smallest difference needed in order to differentiate between two stimuli.

The German physiologist Ernst Weber (1795-1878) made an important discovery about the JND — namely, that the ability to detect differences depends not so much on the size of the difference but on the size of the difference in relation to the absolute size of the stimulus. Weber’s Law maintains that the JND of a stimulus is a constant proportion of the original intensity of the stimulus.

As an example, if you have a cup of coffee that has only a very little bit of sugar in it (say one teaspoon), adding another teaspoon of sugar will make a big difference in taste. But if you added that same teaspoon to a cup of coffee that already had five teaspoons of sugar in it, then you probably wouldn’t taste the difference as much (in fact, according to Weber’s Law, you would have to add five more teaspoons to make the same difference in taste).

Another interesting application of Weber’s Law is in our everyday shopping behaviour. Our tendency to perceive cost differences between products is dependent not only on the amount of money we will spend or save, but also on the amount of money saved relative to the price of the purchase. For example, if you were about to buy a soda or candy bar in a convenience store, and the price of the items ranged from $1 to $3, you would likely think that the $3 item cost “a lot more” than the $1 item. But now imagine that you were comparing between two music systems, one that cost $397 and one that cost $399. Probably you would think that the cost of the two systems was “about the same,” even though buying the cheaper one would still save you $2.

Attention

Attention is the next part of the perception process, in which we focus our attention on certain incoming sensory information. Since we can’t tune in to each and every one of the thousands of messages and images we’re exposed to daily, we tend to only pay attention to information that we perceive to meet our needs or interests. This type of selective attention can help us meet critical needs and get things done.

Consider a hypothetical scenario: your car has finally broken down (for good) and you need to look for something new. You’re feeling stressed about what this is going to cost: a new car, or even a decent used one, will set you back financially. Although car sharing has existed for years now, you’ve never given it any thought: haven’t had to, actually. But now, you take notice of all the reserved parking spots for car sharing at school; and at the mall; and downtown. You start seeing car sharing cars on the road more than you remember seeing before. You start to wonder, “have these JUST appeared now, or has car sharing been this big all along, but I’ve never noticed it before now?”

This scenario points to the principle of salience: a situation in which we tend to pay attention to information that attracts our attention in a particular context. The thing attracting our attention is often something we might consider important, relevant, prominent, and timely. At other times, people forget information, even if it’s quite relevant to them, which is called selective retention. Often the information contradicts the person’s belief. A longtime chain smoker who forgets much of the information communicated during an anti-smoking commercial is an example. To be sure their advertising messages get through to you and you remember them, companies use repetition. Despite how tired we grow of seeing the same commercials over and over (and over, again), advertisers are hoping consumers will retain some of the messages for when a need or want for their brand emerges.

For many brands, however, this is an unacceptable way to get noticed! To have to wait until a consumer has a timely need isn’t strategic or reliable. It could take…forever! Brand salience requires a brand to be top of mind when a consumer is ready to make a purchasing decision. It means the consumer, regardless of need and timing, already knows about you (who you are, what you’re selling, and where to find you) and when it comes time to buy, they choose you over the competition. As you might have guessed, the problem is this: how can a brand be noticed when it lacks salience?

Five Ways to Command a Receiver’s Attention

- Size: Bigger stimuli tend to command more attention.

- Color: Color that differs from its surroundings since contrast helps to make one brand stand out from the competition.

- Position: In North America, ads on the right-hand page of a magazine get more attention than those on the left-hand side.

- Placement: Ads in places where you don’t expect to see them, such as walls of tunnels or on the ground in public spaces, get more attention because of their novel placements.

- Shock: Provocative content and eye-catching design can increase attention, benefit memory, and positively influence consumer behaviour (Dahl, et.al., 2003).

Perceptual defense is defined as, “[a] tendency to distort or ignore information that is either personally threatening or culturally unacceptable” (Rice University, n.d.). This presents a serious challenge for some marketers, particularly those who are designing persuasive messaging that acts as a public service announcement (or PSA). Anti-smoking, anti-drinking & driving, and messaging that confronts an audience on dangerous or harmful behaviour is often ignored because the audience may not identify that the message is for them, or they may be too defensive to process the contents of the message. (This isn’t to say that PSA’s are a waste of time and resources, but instead to highlight the difficulty and complexity in creating effective marketing messages to change behaviours and attitudes when they speak so personally to us).

Perceptual vigilance on the other hand takes place when we, as consumers find ourselves in a position where we pay more attention to advertisements that meet our current needs and wants. While advertisements surround us on a day-to-day basis, we tune out those that are irrelevant or ill-suited to our particular situations. But when our car breaks down and we’re thinking of buying a new one, we may start to “notice” car ads more. Or if we’re considering planning a vacation, we may come to focus more on all the hotel and spa ads we largely ignored in the past.

Maximizing exposure with the intent to become noticed and make a strong impression on consumers is the reason why brands might engage in guerilla marketing. This form of marketing is often unconventional, unexpected, innovative, and memorable. Although it can be risky, when executed successfully guerilla marketing will result in word-of-mouth advertising and with any luck, become a viral sensation. Guerilla marketing differs from hype, which is defined as “extravagant or intensive publicity or promotion” (“Hype marketing,” 2020) and is usually attributed to products that are rare or in limited supply. In resale markets, such as consumer second-hand markets, hype is a driving force of value for products that are perceived to have high social, emotional, and monetary value. Hype built on social media platforms that is created by resellers of rare and much sought-after sneakers, for example, helps to drive the price up beyond the sneakers’ original retail prices.

What is the hidden message in that magazine ad you’re looking at? Are you getting brainwashed by innocent-looking TV commercials that “order” you to buy a product? If you believe advertisers are doing their best to place “secret messages” all around you, you’re not alone. Subliminal perception is a topic that has captivated the public for more than fifty years, despite the fact that there is virtually no proof that this process has any effect on consumer behaviour. Another word for perceptual threshold is limen (just remember “the secret of Sprite”), and we term stimuli that fall below the limen subliminal. So subliminal perception (supposedly) occurs when the stimulus is below the level of the consumer’s awareness.

A survey of American consumers found that almost two-thirds believe in the existence of subliminal advertising, and more than one-half are convinced that this technique can get them to buy things they do not really want (Lev, 1991). They believe marketers design many advertising messages so the consumers perceive them unconsciously, or below the threshold of recognition. For example, several authors single out beverage ads as they point to ambiguous shapes in ice cubes they claim are actually women’s bodies or erotic words. Most recently, ABC rejected a Kentucky Fried Chicken (KFC) commercial that invited viewers to slowly replay the ad to find a secret message, citing the network’s long-standing policy against subliminal advertising. KFC argued that the ad wasn’t subliminal at all because the company was telling viewers about the message and how to find it. The network wasn’t convinced—but you should be (Ruggless, 2006).

Like this KFC ad, most examples of subliminal advertising that people “discover” are not subliminal at all—on the contrary, the images are quite apparent. Remember, if you can see it or hear it, it’s not subliminal; the stimulus is above the level of conscious awareness. Nonetheless, the continuing controversy about subliminal persuasion has been important in shaping the public’s beliefs about advertisers’ and marketers’ abilities to manipulate consumers against their will.

Although some research suggests that subliminal messages can work under very specific conditions, this technique has very little applicability to advertising even if we wanted to resort to it. For one, an advertiser would have to send a message that’s very carefully tailored to each individual rather than to a large audience. In addition, there are wide individual differences in threshold levels (what we’re capable of consciously perceiving); for a message to avoid conscious detection by consumers who have low thresholds, it would have to be so weak that it would not reach those who have high thresholds.

However, a new study surely will add fuel to the long-raging debate. The researchers reported evidence that a mere thirty-millisecond exposure to a well-known brand logo can in fact influence behaviour; specifically the study found that people who were exposed to a quick shot of Apple’s logo thought more creatively in a laboratory task (mission: come up with innovative uses for a brick) than did those who saw the IBM logo (Claburn, 2008). Apple will no doubt love the implication, but most other advertisers are too focused on efforts to persuade you when you’re aware of what they’re up to.

Interpretation

Although selecting and organizing incoming stimuli happens very quickly, and sometimes without much conscious thought, interpretation can be a much more deliberate and conscious step in the perception process. Interpretation is the third part of the perception process, where we assign meaning to our experiences using mental structures known as schemata. Schemata are like databases of stored, related information that we use to interpret new experiences. We all have fairly complicated schemata that have developed over time as small units of information combined to make more meaningful complexes of information.

It’s important to be aware of schemata because our interpretations affect our behaviour. For example, if you are doing a group project for class and you perceive a group member to be shy based on your schema of how shy people communicate, you may avoid giving them presentation responsibilities in your group project because you are of the belief that shy people may not make good public speakers. Schemata also guide our interactions, providing a script for our behaviours. We know, in general, how to act and communicate in a doctor’s waiting room, in a classroom, on a first date, and on a game show. Even a person who has never been on a game show can develop a schema for how to act in that environment by watching The Price Is Right, for example. People go to great lengths to make shirts with clever sayings or act enthusiastically in hopes of being picked to be a part of the studio audience and hopefully become a contestant on the show.

We have schemata about individuals, groups, places, and things, and these schemata filter our perceptions before, during, and after interactions. As schemata are retrieved from memory, they are executed, like computer programs or apps on your smartphone, to help us interpret the world around us. Just like computer programs and apps must be regularly updated to improve their functioning, competent communicators update and adapt their schemata as they have new experiences.

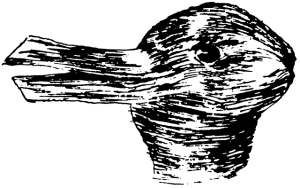

Gestalt psychology The German word gestalt is usually translated as “organized whole” and the catchphrase “the whole is greater than the sum of its parts” succinctly summarizes the major message of this approach. Gestalt psychologists believed that perception was primarily a top-down process involving meaningful units rather than a bottom-up process combining elements of sensation. Only with the aid of prior experience could a consumer meaningfully interpret often ambiguous sensory information. For example, when “reading” picture below, you may determine what constitutes a rabbit versus a duck. Another way of influencing interpretation of an ambiguous image is to establish a perceptual set through exposure to conceptually related images or words. For example, if you first hear the sound of ducks or read the words duck, you would be more likely to perceive the duck than the rabbit.

Adaptation

A fundamental process of perception is sensory adaptation — a decreased sensitivity to a stimulus after prolonged and constant exposure. When you step into a swimming pool, the water initially feels cold, but after a while you stop noticing it. After prolonged exposure to the same stimulus, our sensitivity toward it diminishes and we no longer perceive it. The ability to adapt to the things that don’t change around us is essential to our survival, as it leaves our sensory receptors free to detect the important and informative changes in our environment and to respond accordingly. We ignore the sounds that our car makes every day, which leaves us free to pay attention to the sounds that are different from normal, and thus likely to need our attention. Our sensory receptors are alert to novelty and are fatigued after constant exposure to the same stimulus.

As mentioned at the top of this page, consumers are exposed to thousands of advertising and marketing messages each day. While some ads can successfully break through the noise and capture our attention, over time we may just grow tired of the ad and it no longer interests us. When left unchanged, the ad fails and fades into the background. Tuning out advertisements is a marketer’s nightmare (think of how much they’ve spent to get our attention in the first place!) The question for the marketer becomes this: how much exposure is enough to garner attention, but not so much to reach a state of adaptation where the consumer no longer responds?

When we experience a sensory stimulus that doesn’t change, we stop paying attention to it. This is why we don’t feel the weight of our clothing, hear the hum of a projector in a lecture hall, or see all the tiny scratches on the lenses of our glasses. When a stimulus is constant and unchanging, we experience sensory adaptation. During this process we become less sensitive to that stimulus. A great example of this occurs when we leave the radio on in our car after we park it at home for the night. When we listen to the radio on the way home from work the volume seems reasonable. However, the next morning when we start the car, we might be startled by how loud the radio is. We don’t remember it being that loud last night. What happened? What happened is that we adapted to the constant stimulus of the radio volume over the course of the previous day. This required us to continue to turn up the volume of the radio to combat the constantly decreasing sensitivity. However, after a number of hours away from that constant stimulus, the volume that was once reasonable is entirely too loud. We are no longer adapted to that stimulus!

Media Attributions

- The image of a busy urban crosswalk surrounded by high-rise buildings and outdoor billboard advertisements is by Aaron Sebastian on Unsplash.

- The graphic of “The Perceptual Process: Sensation & Perception” by Niosi, A. (2021) is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA.

- The picture of “Gestalt Rabbit Duck” is a public domain.

Text Attributions

- The first paragraph under “The Perceptual Process”; the first paragraph under “Exposure”; and, the section under “Interpretation” are adapted from A Primer on Communication Studies which is licensed under CC BY 3.0

- The definition of “absolute threshold” and the section under “difference threshold” are adapted from Introduction to Psychology 1st Canadian Edition by Charles Stangor, Jennifer Walinga which is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

- The last paragraph under “Attention”; the H5P content “Five Ways to Command a Receiver’s Attention”; and, the section under” Subliminal or sublime” are adapted from Launch! Advertising and Promotion in Real Time [PDF] by Saylor Academy which is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0.

- The opening paragraph and the second paragraph under “Exposure” are adapted (and edited) from Principles of Marketing by University of Minnesota which is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

- The example of “Absolute Threshold” and the last paragraph under “Adaptation” are adapted (and edited) from Privitera, A. J. (2021). “Sensation and perception“. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF publishers.

- The texts related to Gestalt Psychology are adapted from Psychology by Jeffrey C. Levy is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

References

Claburn, T. (2008, March 19). Apple’s Logo Makes You More Creative than IBM’s. Informationweek. http://www.Informationweek.Com/News/Internet/Showarticle.Jhtml?Articleid=206904786.

Dahl, D. W., Frankenberger, K.D. and Manchanda, R.V. (2003). Does It Pay to Shock? Reactions to Shocking and Nonshocking Advertising Content among University Students. Journal of Advertising Research 43, no. 3: 268–80.

Hype (marketing). (2020, December 9). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hype_(marketing).

Lasn, K., (1999). Culture Jam: The Uncooling of America. New York: William Morrow & Company.

Lev, M. (1991, May 3). No Hidden Meaning Here: Survey Sees Subliminal Ads. New York Times, D7.

Ries, L., (2009). In the Boardroom: Why Left-Brained Management and Right-Brain Marketing Don’t See Eye-to-Eye. New York: HarperCollins.

Ruggless, R. (2006, December 18). 2006 the Year in Review: Even as High Costs, New Regulations and Health Concerns Test Operators, Industry Moves forward with Innovative Products, Proactive Strategies and Big Business Deals. Nation’s Restaurant News. http://www.accessmylibrary.com/coms2/summary_0286-29087275_ITM.

Simpson, Jon. (2017, August 25). Finding Brand Success in the Digital World. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbesagencycouncil/2017/08/25/finding-brand-success-in-the-digital-world/#33f1a1ad626e.

A smell, sound, object or anything else that engages our brain to pay attention and interpret what we have come in contact with in our environment.

When we take new information in, we organize and interpret it based on our prior experiences as well as our cultural norms. Perceptual filters help us make sense of new information and reduce anxiety when faced with the unknown (uncertainties).

A strategy developed by marketers to help influence how their target market (consumers) perceives a brand compared to the competition.

A type of experiential advertising that is highly engaging, unanticipated, unique, unconventional, innovative, and designed with the intent to be memorable and become viral.

Sensory marketing involves engaging consumers with one or more of their senses (see, touch, taste, smell, hear) with the intention to capture their attention and store the sensory information for future processing.

When we deliberately choose to come in contact with information from particular sources (e.g. social media, videos, advertisements, podcasts) we are engaging in selective exposure.

A term that refers to the smallest (minimal) level of a stimuli (e.g. sound; sight, taste) that can still be detected at least half of the time.

The differential threshold - also known as the JND or just noticeable difference - refers to the minimum difference in intensity that can be detected between two objects (e.g. the size of two bags of potato chips or the subtle difference in two logo designs).

This law states that the differential threshold (the just noticeable difference) is a constant proportion (or ratio) of the original stimulus.

Following "exposure" in the perceptual process, Attention describes the dedicated effort and focus we give to incoming sensory information (e.g. sights, sounds).

A term that describes our focused commitment to only some of the stimuli and senses that we come in contact with, based on what is relevant to our needs and/or interests.

A term used to describe objects or stimuli that attract and hold our attention because we find them important relevant, prominent, or coming into our lives in a timely manner.

A term used to describe when we forget information, despite it being important for us to retain and interpret (e.g. public service announcements that may help us live a better life, but we do not retain because we are uncomfortable with the idea of confronting our habits and/or behaviours).

In a marketing context, this occurs when consumers distort or ignore advertising messages that we may feel are personally threatening, uncomfortable, or even culturally unacceptable.

In a marketing context, this occurs when consumers pay more attention (committed focus) to advertising messages that are relevant to our current state of being and/or meet our current unmet needs and wants.

Hype is a form of intense publicity and promotion that helps drive up the value of consumer goods and services. Consumers and resellers use social media platforms to exchange information and discuss products that are rare and sought-after are "hyping up" a good, which often results in a higher resale price.

The belief that "hidden messages" in marketing are effectively influencing consumers to engage in specific decision making behaviour (e.g. secret messages telling consumers to buy certain brands).

A threshold (like an invisible line) that separates what one can perceive and what one can't perceive: stimuli (sounds, sights) that fall below the limen are considered "subliminal" (not detectable, or below our own awareness level) and stimuli above the limen we detect and are aware of.

Following exposure and attention, Interpretation is the third part of the perceptual process and occurs when we give meaning to information and messages that have gained our attention.

Described as being like "databases" in our memory, the schemata contains stored information based on our past experiences that help us make sense of and interpret new experiences.

meaningful units based on prior experience are used to determine the elements of sensation

sensory elements are combined to perceive meaningful units

This term describes a decreased sensity to stimulus (information/messages) after a long period of constant exposure. For consumers, this may be described as a form of (marketing/advertising) fatigue where they tune out (become less sensitive to) the same stimulus (ad) over time.