Chapter 4: Storytelling and Public Speaking

Hasina walked to the front of the classroom to give her speech. She wiped her sweaty hands on her pants, stood up straight, and then popped into character and began with a story…

“Shh…” Emma whispered to her boyfriend Sam.

Hasina looked up at her audience and continued…

It was midnight on Halloween and Emma was doing research for an article she was writing for their high school newspaper on the Black Angel of Death, a tombstone located at the Oakland cemetery in Iowa City. They had come to see the famously cursed tombstone with their best friends Autumn and Adam.

“It is all moldy looking and ugly,” Sam lamented.

Emma sighed, “Don’t make fun of it. You’ll die. Some guy made fun of it in 1982 and he was struck by lightning the next week.”

“There’s no way that is true,” Adam said.

“It is!” Emma exclaimed. “There are several stories of people getting struck by lightning after interacting with the tombstone. That’s how it turned black. The stone was struck by lightning.”

“I thought it turned black because the woman, Theresa or whatever her name was, cheated on her husband,” Autumn chimed in.

“I heard the woman was killed and every year the angel turns a shade darker on Halloween.”

“I don’t believe any of the stories,” Sam declared. “I’m kissing it,” and he began to climb up the tombstone.

“Nope. No way. I’m going back to the car,” Autumn said as she turned and began walking quickly to their car.

Emma pulled on Sam’s shirt, “Get down, Sam. Come on.”

“Do you really believe if I kiss this thing, I’ll die in a week?” Sam asked and then planted a kiss on the angel’s face.

“Oh my God, did you see that?” Emma asked. “The angel’s eyes turned white.”

“No way!” Adam said.

“Let’s get out of here!” Emma cried.

“Come on, you all!” Autumn yelled from the car.

Adam and Sam looked at each other with a smirk.

“Wait a minute,” Adam said to Sam, “If the eyes turn white, does that mean you are a virgin?”

The class laughed, as Hasina paused and looked around the classroom. Just as she had hoped, her classmates were on the edge of their seats and enjoying the story. Hasina began again…

“Today, I’m going to teach you about adolescent legend trips, beginning with a locally famous one…”

In the above example, Hasina began her presentation with a popular Iowa urban legend: The Black Angel of Death. Urban legends are impactful stories full of concrete details, emotions, and surprises that make them easy to remember and pass on to others. Like other types of stories, an urban legend may inform, advise, warn, or entertain. For this reason, urban legends also are effective attention getters in a presentation. In this chapter, we will talk about why storytelling is a powerful communication tool. We will share common dramatic structures and story arcs, provide you with tips on how to tell a captivating story, and point to the best places in a presentation to integrate a story.

What is a Story and Why do Stories Matter?

One thing we all have in common is stories. We tell stories with our families and friends, we tell stories at work, at home, and in the spaces between. But what is a story? Donald E. Polkinghorne (1988) defines story as “a meaning structure that organizes events and human actions into a whole, thereby attributing significance to individual actions and events according to their whole” (p. 18). In other words, a story is how what happens affects someone or something. Stories can be fictional, hypothetical, personal or, as with the case of urban legends, collective creations. Stories reflect and create values and norms, and they help us make sense of the world. Stories are useful tools to use in public speaking situations because they help you connect with your audience, make you or your topic more relatable to your audience, and ultimately make your presentation more memorable.

Stories make you human. At the 2016 Democratic National Convention, Michelle Obama shared a powerful story about sending her children off to school for the first time as children of the President of the United States of America. She said:

Although there are elements of Michelle Obama’s story that are unique to her position as the First Lady, much about this story is relatable. Any parent or caregiver, for example, can connect to the profoundly complex emotional experience of sending your child off to school for the first time. Stories that tap into meaningful moments of the human experience and can help speakers connect to their listeners in powerful ways.

One way stories tap into the human experience is through empathy. Empathy is the ability to take on the perspective of others. Pelias and Shaffer (2007) define empathy as “a qualitative process in which individuals understand and share the feelings of others” (p. 99). This definition recognizes that empathy is something you can learn and suggests that empathic responses may vary in their degrees of understanding. Stories help people gain an awareness of other people’s state of feeling and may even transport people into the story in a way that invites them to take on another’s emotional state. In this way, stories become an intercultural encounter or a way to begin understanding someone who is different from you.

Stories can also make complicated material or abstract ideas more accessible and attainable. Stories not only bring information to life, they also offer an organizing structure to new experiences and knowledge. In a book on children and learning, Wells (1986) stated, “Constructing stories in the mind– or storying, as it has been called– is one of the most fundamental means of making meaning; as such it is an activity that pervades all aspects of learning” (p. 194). Visual learners appreciate the mental pictures stories evoke. Auditory learners are engaged by the speaker’s voice and choice of words. And, kinesthetic learners will gain knowledge through the emotional connection and feelings stories provoke. By tapping into various types of learning, stories have the ability to make knowledge accessible.

Finally, stories matter because they make ideas stick. Multiple studies have shown that stories make information more memorable than facts alone. In 1969, students at Stanford were asked to memorize a list of 12 words. One group of students was instructed to study the words for 2-minutes. The second group of students was told to create a story using the words in the 2-minute time period. When asked to recall the words, 93% of the people in the story group were able to recall words, while only 13% were able to in the other group (Bower & Clark, 1969). In 2001, Banister and Ryan published a study that demonstrated that children remembered abstract science ideas more effectively when taught in a story format (Banister & Ryan, 2001). And in 2007, the Heath brothers conducted an experiment where students gave presentations and then 10 minutes later their audience was tested to see what they remembered (Heath & Heath, 2007). When it came to remembering the presentations, only 5% of the audience could recall any individual statistic, but 63% of the audience could remember the stories.

Stories have the ability to bring your presentation to life. By using stories in your public speaking, you will seem more relatable to your audience, cultivate connections with and for your audience, evoke empathy, as well as make information more attainable and more memorable. In the next section, we will teach you various dramatic structures and story arcs to aid you as you construct stories to include in your presentations.

Dramatic Structures and Story Arcs

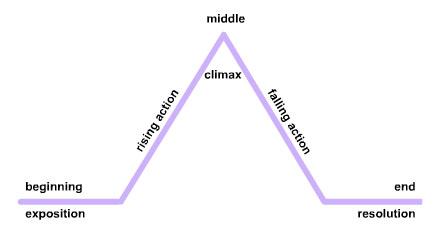

Many scholars, philosophers, and scientists have attempted to understand how stories work throughout time. German novelist and playwright, Gustav Freytag developed what is now known as Freytag’s pyramid in the 19th century. It has become a common tool for storytellers; perhaps you have seen it before?

Freytag’s pyramid contains 5 parts: exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, and dénouement or resolution.

Exposition: The beginning of the action is called exposition. This provides listeners with background information about the story, such as the setting in which the story takes place and character introductions. Usually, the exposition paints a picture of what “normal” life is like before introducing a conflict that disrupts the “normal” and sets the story in motion.

Rising Action: Now having entered a new “normal,” the protagonist or main character establishes a goal. Rising action is the set of complications or obstacles the protagonist encounters along the way.

Climax: After encountering a series of complications, the protagonist must face the situation head on. The story reaches a turning point. Here the situation may go from good to bad or from bad to good.

Falling Action: After the climax, conflict unravels. Life slowly returns to “normal” as the protagonist faces the consequences of their decisions. Things are still happening in the story, but action is deescalating.

Dénouement: Dénouement is the French word for “untying.” During this final stage of the story, loose ends are resolved, questions are answered, and a new normal is established.

Although some believe the dramatic structure laid out in Freytag’s pyramid is best suited for tragedies, many stories incorporate the dramatic elements. Consider recent books, movies, or television shows you have watched recently. How many of them use a similar structure?

Another common story structure is credited to William Labov and Joshua Waletsky (1967), two researchers who studied narrative. This model was developed for personal narratives and included six parts: an abstract (what, in a nutshell, is this story about?); an orientation (who, when, where, why?); the complicating action (then what happened?); evaluation (so what? how is this interesting?); a result or resolution (what finally happened?); and a coda (that’s it, I’ve finished and am bridging back to our present situation). You might notice the similarities between this model and Freytag’s pyramid.

In addition to understanding dramatic structures, it may be helpful to familiarize yourself with typical story arcs. A story arc captures the flow of the events or the plot of your story. Author Kurt Vonnegut (1981) wrote a famously rejected Master’s thesis in which he identified commonly used emotional arcs in stories. “Man in a hole” and “Cinderella” are two arcs that emerged from his work. The idea of finding commonalities among stories caught on. In 2017, Andrew James Reagan built on Vonnegut and others’ work in his dissertation by examining 1,327 books. Reagan (2017) found support for 6 different story arcs:

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

- “Rags to riches” (rise)

- “Tragedy” or “Riches to rags” (fall)

- “Man in a hole” (fall-rise)

- “Icarus” (rise-fall)

- “Cinderella” (rise-fall-rise)

- “Oedipus” (fall-rise-fall)

-

-

-

-

-

-

Each story arc contains the elements of dramatic structure but how they are arranged differs. For example, “man in a hole” story arc begins with a protagonist whose life is going pretty well. Then an event or a series of events occur, and the protagonist’s life takes a plunge. The rest of the story details the protagonist’s life improving or slowly rising back up from the hole.

Understanding dramatic structures, story arcs, and their relationship to each other can help you determine the purpose of your story. Why are you including this story in your speech? What point is the story helping you make? It can also help you clarify your character’s motivations, consider the pacing of your story, and highlight the thematic components of your story so that you can better connect it to the rest of your presentation. Now that you understand why stories matter and some basic dramatic structures and story arcs, we will provide you with tips on how to tell a captivating story.

How to Tell a Captivating Story

A professor of philosophy stands before his class with an empty jar. He begins to fill the jar with rocks. Once the rocks reach the top, he asks his class if the jar is full. The class agrees, the jar is full. Then the professor picks up a handful of pebbles and begins to pour them into the jar of rocks. The pebbles shift and tumble filling up the empty spaces in the jar. The professor asks the class again if the jar is full. The class laughs and agrees that, yes, now the jar is full. The professor then picks up a box of sand and pours it into the jar. The sand shifts and tumbles filling up the remaining gaps in the jar. The professor then tells the class that the jar represents their life. The rocks are the most important things in your life, such as your family, community, or health. The pebbles represent other important things in your life like school or work. The sand is little things in life that have less significance than the rocks and pebbles. If you put the sand in the jar first, there is no room for the rocks and pebbles but if you prioritize the rocks then you can fit the pebbles and sand in as well.

Perhaps you’ve heard this story about rocks, pebbles, and sand? This story has been used in books, blogs, TikTok videos, and podcasts on time management to help emphasize the importance of prioritization. It is unsurprising that the story is so successful. It uses a powerful and vivid metaphor to help readers visualize prioritization. But what makes this story stick? Why has it been repeated over and over again? To conclude this chapter, we will offer several principles for making a story stick and several additional tips for telling a captivating story.

In Chip and Dan Heath’s 2007 book, Made to Stick, they outline principles that make stories stick: 1) Simplicity, 2) Unexpectedness, 3) Concreteness, 4) Credibility, and 5) Emotions. Consider the story about the professor and prioritization: The simple structure of the professor adding items to a jar makes the story easily repeatable. And yet, the story also piques your curiosity. Is the jar full? What is the lesson the professor is trying to teach?

In the story, the professor violates expectations by proving that the jar is not actually full. Next, the story makes the abstract concept of prioritization concrete. You can imagine taking a jar and conducting the same actions the professor does in the story. This not only makes the story concrete, but it also adds to its credibility. In the story of rocks, pebbles, and sand, the expertise of the professor is highlighted but the story also earns credibility because of its believability. Finally, a story sticks when you make your audience feel something.

Did this story compel you to consider your own life’s rocks, pebbles, and sand? Which do you put in first? Have you struggled to “fit it all” into your life’s jar? When composing stories for your presentations, consider if they meet the principles of 1) Simplicity, 2) Unexpectedness, 3) Concreteness, 4) Credibility, and 5) Emotions. If your story meets these criteria, it is more likely to stick with your audience long after your presentation.

Finally, having a good story to share is not enough. How you tell the story matters. In order to consider how best to tell a story, you must first recognize that somebody tells a story. A story comes from a person with a physical body. Based on that body, audience members may make assumptions about a person’s sex, race, class, age, ability, and so on. These aspects of a person, as well as the assumptions made about that person, may impact the performance and the interpretation of the story. Prior to telling a story, consider your own identity and how it may influence the telling of the story you have chosen to share.

For example, imagine your story includes a character with an Appalachian accent. Will you perform it with the accent? How does performing that accent affect how people perceive the character? Is it appropriate or ethical for you, based on your own identity, to take on that voice? By taking into consideration your own identity/culture (see Chapter 2), you will better be able to choose appropriate stories to share as well as thoughtful and ethical ways to share them. Recognizing that somebody tells a story encourages you to think about how your audience may perceive you as a speaker. Then, you can craft your stories and presentation in a way that is responsive to those perceptions.

By acknowledging that somebody tells a story, you also identify how voice, gestures, bodily postures, and other nonverbal aspects impact storytelling. What would happen if, for example, Hasina lowered her voice and leaned in as she shared her story? Or, made eye contact with her audience? How one delivers a story can impact how it is received by the audience. To captivate an audience with storytelling, you must have strong delivery skills, which is discussed in Chapter 6 of this textbook.

Taking into consideration where in a presentation to include a story is an important element to consider. Stories can be integrated throughout a speech. They make fantastic attention getters, as demonstrated with the example of Hasina sharing an urban legend to start her presentation. Stories can also be used within the body of a speech to emphasize a point or help explain a complex idea. They may also be used at the end of a presentation to bring all your arguments together or to synthesize your material. Sometimes a speaker will tell a story across the entire presentation, placing the exposition and rising action near the start of the speech, the climax of the story within the body of the speech, and leaving the falling action and dénouement for the conclusion of the speech. Regardless of where you decide to include a story, it is important for the story to have a clear purpose and to be clearly connected to the rest of the material in the presentation.

Conclusion

Consider the story that opened this chapter: The Urban Legend of the Black Angel of Death. This urban legend, like many others, is simple. Teenagers go to a cemetery to test if the tales are true and get spooked. Hasina shared the story with a clear purpose: To gain the attention of the audience and introduce the concept of adolescence legend trips, the topic of her speech. The story immediately connected to her audience with an example of an experience they could relate to and, in the process, made the concept of legend trips concrete. Throughout this chapter, we have examined why storytelling is a powerful communication tool. We shared common dramatic structures and story arcs, provided you with tips on how to tell a captivating story, and pointed to the best places integrate a story into a presentation. You now have the tools to bring your presentations to life with the power of story.