Chapter 10. Reading and Writing Across Content Areas – Disciplinary Literacy

Emily Hayden and Constance Beecher

“Wisdom is not a product of schooling, but of the lifelong attempt to acquire it” – Albert Einstein

From birth, children use their voices and developing speech sounds to communicate, and they make sense of the world through language. Perhaps you have noticed that children who are engaged in play or other activities often talk simultaneously about what they are doing, using talk to plan their next steps or to generate solutions to some problem they have encountered in the course of their work or play. Vygotsky (1986) believed that language and thought were practically inseparable. The internal and external language children engage in while they are learning advances their reasoning and problem-solving abilities. Later, these processes can be replicated through writing – another way to use language. These literacy skills, talking and listening, as well as writing and reading, should be used in all content areas in the elementary classroom to help students learn new information.

Literacy in content-area classes

The academic standards in mathematics, science, and social studies acknowledge that children use language and literacy to make sense of what they are learning. The same literacy skills taught in English Language Arts (ELA) can be used to help students gain knowledge and master these content areas as well.

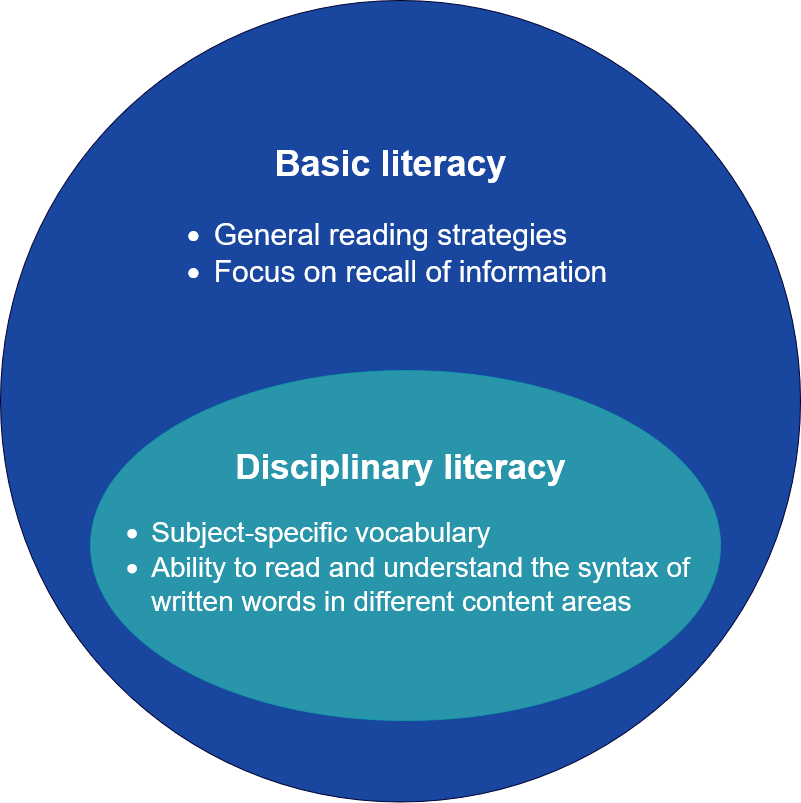

The CEEDAR Center (Collaboration for Effective Educator Development, Accountability, and Reform) illustrates essential literacy skills that are used across content areas. Teaching your students to use their skills and strategies to make sense of texts they read in science, social studies, and mathematics can be called disciplinary literacy.

Disciplinary literacy and content-area literacy

You may have heard of both content-area literacy and disciplinary literacy. Content-area literacy refers to strategies that can be used to make sense of text in any content area. For example, a KWL chart (what I KNOW, what I WANT to know, and what I LEARNED) can be used in almost any context to organize learning before and after reading texts. Here’s a sample lesson using the KWL method entitled Let’s Build a Snowman.

However, there are ways to use literacy strategies that are specifically suited to certain content areas or disciplines. This is disciplinary literacy. Disciplinary literacy recognizes that reading, writing, and other language processes vary depending on the discipline. For example, the literacy skills for mathematics include the ability to read and write number sentences, using particular symbols and conventions. The following number sentence:

2 + 9 = 11

uses two symbols generally seen only in mathematics: + and =. Likewise, there are certain literacy comprehension tools and strategies that are especially suited to the requirements of mathematics. For example, a T-chart may be just the right comprehension tool to use when developing an important mathematics skill – separating necessary information from unnecessary information in a story problem, as shown below:

Sammy and three friends want to share a pizza. The pizza is cut into 12 pieces. They all think that pepperoni is the best kind of pizza. If Sammy and her three friends each get the same number of pieces, how many will each person get?

T-Chart to organize information in a story problem.

|

Information I need to solve this problem |

Extra information that I do not need |

|

Sammy and three friends want to share a pizza. |

|

|

The pizza is cut into 12 pieces. |

They all think that pepperoni is the best kind of pizza. |

|

Each person gets the same number of pieces of pizza. |

|

Components of disciplinary literacy

Choosing the best-fitting comprehension strategies for a discipline depends on recognizing several components of disciplinary literacy:

- Learning the specific vocabulary of a discipline is essential for gaining knowledge in that discipline.

- Reading and writing are used differently in mathematics, science, social studies, and ELA.

Watch this video about the sun. Make a list of some subject-specific vocabulary words used in this video that you would want to teach students who were learning about the sun. Compare your list with those of your classmates.

Maybe your vocabulary list looked something like this:

- Energy

- Light

- Surface

- Fahrenheit

- Celsius

- Dwarf star

Reading and writing are used differently

In the mathematics T-chart example above you saw how a specific graphic organizer could help with a specific mathematics language task: sorting necessary from unnecessary information in a story problem. The ability to determine the relevance of information is a highly complex and challenging task; and while there are times when students will need to sort information in this way in social studies, science, and ELA, this task occurs early and often in mathematics instruction. This is one way that reading is used differently in mathematics.

Social studies experts and scientists also use reading and writing in ways that are unique to their disciplines. For example, in elementary social studies tasks, students are asked to determine cause and effect relationships and to use timelines to keep track of events. In elementary science tasks, students record observations and hypothesize about outcomes. Classroom learning in the early elementary years establishes these discipline-specific ways of using literacy; and like all other early learning, these skills are expanded on in later school experiences. A strong base of disciplinary literacy skills is crucial for later success.

How to start

You can help your students establish a strong foundation of disciplinary knowledge by incorporating reading, writing, speaking, and listening into as many learning activities as possible. A good way to start is by reading informational texts to explore topics of student interest, because having a purpose for reading enhances students’ engagement. Dr. Nell Duke, a literacy researcher, has studied informational text. In her blog post for the National Association for the Education of the Young Child, Dr. Duke suggests the following:

- Read informational texts to learn how to care for a class pet.

- Write instructions for something of importance, for example, how-to instructions for the staff who will be taking care of the school garden over the summer.

As students become more comfortable with informational texts, use such texts to introduce new topics and to set a purpose for the learning to come:

- Read and compare a few informational texts to prepare for a class field trip or to get an overview of a new topic at the start of the unit.

For example, you might read 12 Ways to Get to 11 (Merriam, 1996) as a way of introducing how to conceptualize and write math number sentences:

Some published curricula will include suggestions for companion texts and writing activities. For example, see this open-access social studies lesson: What Makes a Hero?

Sometimes you will need to think of your own ways to include literacy. Look again at the lesson example for Let’s Build a Snowman. By clicking on the Resources & Preparation Tab you will see three texts, fictional and informational, that were chosen to help students build the knowledge and disciplinary ways of thinking that are needed for this lesson.

What about science?

Scientists also use reading and writing in very specific ways, and young children can begin to practice these disciplinary literacy skills. See this slide show for some ways that literacy use in science compares to that in ELA, and for student writing examples.

Writing

An effective way for young children to start writing in any discipline is to make lists.

You try it! Start by making a list of things you see (observe) in this picture:

I see …

Now, think like a scientist and generate some questions.

I wonder …

Once again, work with a partner to search online book sites and find at least three texts (both fictional and informational) that you could use to learn about your questions.

Generate some vocabulary words to teach as well.

The disciplinary literacy skills that children learn in the primary grades will set the stage for learning across the content areas in the middle grades and beyond. Learning to use the literacy components – reading, writing, speaking, and listening – in mathematics, science and social studies depends on knowing

- the vocabulary that is essential for gaining knowledge in that discipline; and

- that reading and writing are used in different and unique ways in mathematics, science, social studies, and ELA.

Resources for teacher educators

- KWL Chart [PDF]

- Olness, R. L. (2022). Let’s build a snowman.

- Hayden, H. E. (2018) Reading and writing in science. [Powerpoint slides]

References

Carr, J., (2020). Math read-aloud: 12 ways to get to 11. https://youtu.be/rJJ1HhSv4LY

Council of Chief State School Officers. (2011, April). Interstate Teacher Assessment and Support Consortium (InTASC) Model Core Teaching Standards: A Resource for State Dialogue. Washington, DC.

Disciplinary Literacy. CEEDAR Center: Collaboration for Effective Educator Development, Accountability, and Reform. https://ceedar.education.ufl.edu/.

Duke, N. K. (2019). Making the most of informational text. https://www.naeyc.org/resources/blog/making-most-informational-text

Hayden, H. E. (2017). Horses at the Iowa State University horse barn.