Chapter 9. Literacy Instruction for Diverse Learners

Constance Beecher; Sohyun Meacham; and Nandita Gurjar

“We have become not a melting pot but a beautiful mosaic. Different people, different beliefs, different yearnings, different hopes, different dreams.” – Jimmy Carter

“We should all know that diversity makes for a rich tapestry, and we must understand that all the threads of the tapestry are equal in value no matter what their color.” – Maya Angelou

Keywords: cultural literacy, dual-language learners, universal design for learning, trauma-informed instruction

Imagine a class with diverse kids – some with invisible or visible disabilities, different ethnicities, and nationalities – who feel a sense of belonging and whose cultural capital, customs, traditions, and languages are valued in the classroom space. The teacher focuses on building relationships with each child to scaffold and enrich their learning as s/he has an undaunted belief in their capabilities and strengths. In this nurturing environment, every child could blossom and reach for the stars. This is the class every child deserves, no matter where they come from or where they are going!

Culturally responsive instruction begins with getting to know our students – their home lives and cultures. Having an appreciation and respect for each child and their cultural and linguistic backgrounds and leveraging them in classroom instruction in reading and writing lets the children know that they belong in the classroom community. A positive self-concept and self-esteem are crucial for learning and engagement to occur. Therefore, it is the teacher’s job to embrace and welcome each child’s cultural and linguistic identities to foster a culturally inclusive learning environment.

Teachers should build relationships with parents and students and welcome parents as volunteers and guest speakers into the classroom space. Invite parents to read a folktale, fable, myth, or legend from their culture to the class. Have “Show and Tell” days where children can bring cultural artifacts to show their peers and take pride in who they are. During reciprocal teaching, they can teach a peer some expressions from their native language or a song from their culture. Also, ensuring that the child sees themselves in the literature they read is vital for their self-concept. Therefore, having books that are mirrors, windows, and sliding doors (Sims Bishop, 1990) will ensure that all children see themselves in literature and media.

To get to know your students and their families, learn about their family literacy practices. Some children come from an oral storytelling tradition where they grow up listening to stories from grandparents, uncles, and aunts or learning family arts and crafts such as quilt making and basket weaving; these are all valid family cultural practices that contribute to building the children’s native language and cultural literacies, upon which school literacies are built.

Begin with family cultural literacy practices

Alma Flor Ada (2003) reminds us: “Students live in two worlds: home and school. If these two worlds do not recognize, understand, and respect each other, students are put in a difficult predicament (p.11)”; and very little learning can occur. The Global Family Research Project emphasizes that literacy begins at home.

Culturally and linguistically diverse parents value literacy and see it as the single, most powerful hope for their children’s future (Ordonez-Jasis & Oritz, 2006)

Researchers who study diverse learners say that teachers must talk with families to understand their lives outside of school. Teachers will see a complete picture of the families’ socio-cultural contexts, and they will also recognize the wealth of stories, history, motivations, and cultural information, or “funds of knowledge” (Moll & Gonzalez 2004), that the parents contribute to their children’s literacy learning. These funds of knowledge become the building blocks for a comprehensive literacy program. Positive early literacy experiences in families – reading with a parent, grandparent, or aunt, visiting the library, or enjoying books with other children at their childcare prepares them to learn to read at school. Here are seven research-based ways families contribute to the child’s literacy development:

- Creating a literacy-friendly home environment.

- The number of books in the home is a predictor of the children’s success in reading.

- Reading to children and asking questions about the story builds vocabulary, letter knowledge, and comprehension.

- Having lots of conversations.

- Children need to hear a lot of language from birth in order to grow the neural networks that are the basis of their language development.

- The number of words children hear by age 3 strongly predicts kindergarten readiness.

- Having high expectations for the children’s learning.

- When parents believe their children will succeed in school, their children have greater success than the children of parents who do not believe it.

- Making reading enjoyable.

- When families nurture encouraging interactions, the children are interested in reading, which helps their literacy skills grow.

- Adults benefit too – these enjoyable experiences help reduce stress!

- Families use their home language.

- Around 25% of young children in the U.S. are learning two languages at the same time.

- Using the home language helps the children build vocabulary and have a healthy self-identity.

- Families and teachers communicate.

- Research clearly shows that when parents are involved with a child’s schooling, the children’s learning is enhanced.

- Schools/childcare centers can invite the parents into the classroom and share information so they can support their children.

- Visiting the library.

- Kindergartners who visit libraries with their families score higher on assessments of reading, mathematics, and science in third grade than those who rarely visit.

It is important for teachers to connect with families and validate their roles in their children’s learning. After all, children only spend around 25% of their waking time in school! (Wherry, 2004).

Diversity and children’s Books

Diversity and social justice are two key themes in literacy-education research today. This research focuses on teaching children to understand the diversity within human beings in this world and injustice issues associated with the diversity. In this context, scholars use “multicultural children’s literature” as the term for the children’s literature that deals with diversity and social justice (Cai, 2002). In many early childhood classrooms, multicultural picturebooks from different countries are considered to be the main resources for diversity education. However, the use of international picturebooks may not be sufficient to reduce our children’s cultural biases and develop their ability to make social changes. Helping our children become aware of injustices perpetrated because of cultural differences and to actually act on the issues should be an ultimate goal when exposing them to multicultural picturebooks. Botelho and Rudman’s (2009) critical multicultural analysis of children’s literature gives us some ideas about how to use multicultural picturebooks in attaining this goal. Introducing the topics of race, gender, and social class, they emphasize that understanding who exercises the power in our society, where these three aspects of humanity are intertwined, is a key consideration when deciding which picturebooks to read with our children and what conversations we will have with them.

Facilitating critical reading

In addition, critical reading is something we should promote during read-alouds with our children, after selecting culturally sensitive, high-quality multicultural picturebooks for our classroom library. High-quality texts do not overly explain the story, to invite readers to “draw their own conclusions without being told precisely what to think ” (Young et al., 2020, p. 32). Quality multicultural picturebooks do not necessarily tell the systemic factors regarding social inequity but show the issues. In addressing them, the adults’ role in facilitating critical conversations around the readings with the children is significant (Quast & Bazemore-Bertrand, 2019).

Last Stop on Market Street, written by Matt de la Peña and illustrated by Christian Robinson, is a multicultural picturebook that stands out in my mind. This book is frequently discussed in the recent literacy-education literature that focuses on diversity and social justice. It deals with economic inequality portrayed in an urban U.S. context. The main storyline follows CJ’s bus rides with his grandmother. He usually takes the bus with his grandma after church, even on rainy days. Although in the early part of the story he questions why he needs to take the bus but his friend rides in the family’s car, he and his grandma find real beauty around them during their bus rides.

CJ needs to ride the bus because they don’t own a car. CJ asks his grandma, “Nana, how come we don’t got a car?” Grandma responds, “Boy, what do we need a car for? We got a bus that breathes fire, and old Mr. Dennis, who always has a trick for you” (De la Peña, 2015). In the United States, the use of public transportation is often associated with poverty. Cities and towns there have been built primarily for people with personal vehicles. Therefore, except for metropolitan areas such as New York and Chicago, the use of public transportation is an inconvenience that mostly people on low incomes end up needing to bear. Rather than complaining about the situation, however, CJ’s grandma and he talk about enjoyable things. They focus on people that they enjoy seeing and being with – from the bus driver to a guitar player.

While deficit views and devaluing the cultures of people in poverty are prevalent in society (e.g., they are lazy; something’s wrong with them), Last Stop on Market Street supports the counter-narrative. The last stop, which CJ and his grandma get off at, is a soup kitchen where they volunteer weekly. They are not lazy. They are helping others.

Race is not explicitly spoken of in this book, although readers can see CJ’s skin color is dark. This is where we can have a critical conversation about how people with certain racial backgrounds tend to experience poverty more often than others, and about “how people from all different racial, ability, and cultural backgrounds might share similar poverty experiences” (Quast & Bazemore-Bertrand, 2019, p. 221). As the book does not speak about the reasons for CJ and his grandma’s current economic condition either, more critical conversations between the teacher and the children will be needed for the children to become aware of systemic factors contributing to inequity.

Last Stop on Market Street speaks about the Blind culture (capitalized to indicate that this person belongs to the Blind culture, not just that they do not see) a little more explicitly than racial issues. Another rider on the bus is Blind. When CJ sees the man, he asks his grandma, “How come that man can’t see?” A conversation among this man, CJ, and his grandma ensues in which it is revealed how the Blind culture has a rich appreciation of their world because of their enhanced olfactory and auditory senses. The man tells CJ’s grandma that he even closes his eyes to feel music.

Last Stop on Market Street is a rare picturebook, earning a Newbery Medal, an award that is not for the illustrations but for the quality of the writing. Considering that most of the books receiving the Newbery Medal are chapter books, the accomplishment of this picturebook is remarkable. It is also notable that Matt de la Peña is one of only three Latin-background authors to have won the Newbery. This talented author also won Pura Belpré Honor Book Awards for both this book and his young-adult novel The Living, in 2014. The Pura Belpré Award was founded in 1996 to celebrate the work of Latinx writers and illustrators. Christian Robinson, the African-American illustrator of Last Stop, won the Coretta Scott King Illustrator Honor Award; Coretta Scott King Book Awards have gone to one African-American author and one African-American illustrator annually since 1974. Last but not least, this book won the Caldecott Honor in 2016.

The urban atmosphere as depicted in Robinson’s paintings and collages can make us feel some human warmth, rather than seeming merely cold, sterile, and industrial. His illustrations effectively delineate a remarkable level of diversity among the characters through the many different shades of people’s skin color, hair texture, clothing, gestures, props that the characters hold or use, and whatnot. This quality is also evident in Robinson’s more recent wordless picturebook titled Another, which was published in March 2019. In both of the books illustrated by Robinson, he only uses dots for people’s eyes, although the colors of the dots vary. By doing so, the illustrations avoid potentially stereotypical eye shapes (e.g., thin slanted eyes).

In conclusion, we should reiterate that there are many things that are not explicitly articulated in Last Stop on Market Street, while it delineates an unexpected beauty in the experiences of people who live in poverty. Children’s literature scholars suggest that quality multicultural children’s literature should “avoid the single story or allowing one story to speak for an entire group of individuals” (Young et al., 2020, p. 81). This book does not attempt to speak for an entire group of people in poverty, people of color, or people with (dis)abilities. Still, it vividly depicts cultural specificity, which makes it a high-quality multicultural picturebook (Sims Bishop, 1992). Picturebooks like this can foster our children’s intercultural understanding and the development of empathy.

DLL strategies in reading and writing

Dual-language learners’ and emergent bilinguals’/multilinguals’ needs should be addressed based on the policies and standards of the Iowa Department of Education. The number of English-language learners continues to increase in Iowa, which it has by almost 60% since 2010 (per the Iowa Department of Human Rights). One hundred seventy-seven languages were spoken by 31, 236 students in Iowa in the year 2020-2021 (Iowa Department of Human Rights). Here is a poster with the number of languages spoken in Iowa [PDF]. There are 18 languages spoken in Black Hawk County, where the University of Northern Iowa is located. Crawford County has the highest number of ELL students (32.7%) followed by Buena Vista with 26% and Marshall with 24.7%. There is an 83% increase in Iowa in the number of foreign-born residents. Embarc, in Waterloo, Iowa, is a non-profit community-based organization that addresses the needs of refugee children who migrated to Iowa due to socio-political upheavals.

We have a moral responsibility to reduce barriers and enhance educational, healthcare, and supportive services for ELLs, especially those who are new to the country and culture, and students with disabilities. The following inclusive strategies should be incorporated while reducing barriers for diverse learners in Iowa.

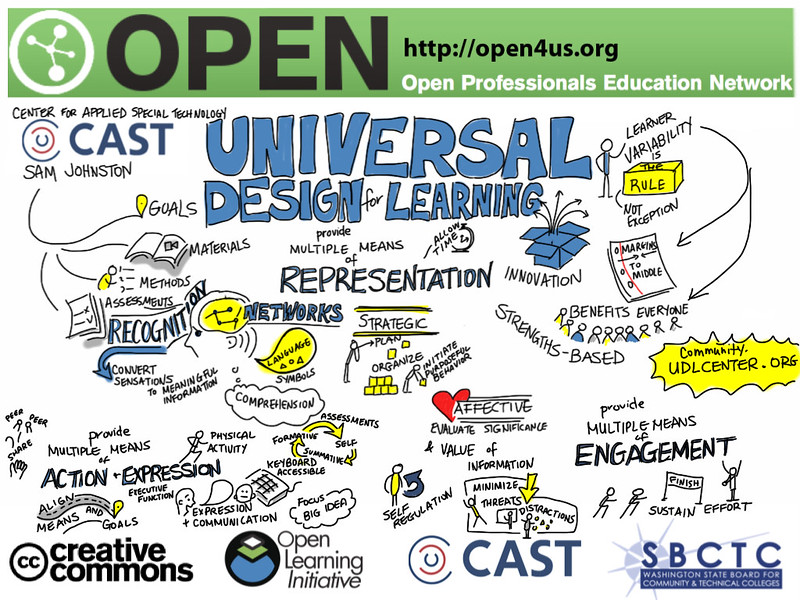

Incorporate Universal Design for Learning

Watch this video on the Universal Design for Learning for addressing the needs of diverse learners by adapting our instruction to meet their needs.

ELL strategies

It is important to reduce anxiety in newcomers and second-language learners. We should aim at lowering the affective filter of our students so they can function at their best. It is important for us to understand the silent phase of language acquisition: second-language learners go through a period in which they are quiet but very receptive to comprehensible input. During this phase, the teacher’s job is to continue to provide comprehensible input with visuals, gestures, and simplified language, without slang or idioms. If you choose to include idioms, explain them in a simple form through writing and drawing. Idioms are very hard to understand, as they are culturally specific.

Comprehensible input (Krashen, 1981) is the linguistic input that can be easily understood. It usually has more than one mode of expression. Along with simplified verbal expressions, other means of communicating used to make material clear and easily understood by second-language learners include visuals, videos, gestures, simulations, and hands-on experiences such as movement.

Motivate ELLs by engaging them in authentic reading and writing activities. Motivation plays a huge role in engagement. Relevance, interest, confidence (expectation of success), and satisfaction (enjoyment, extrinsic reward) play important roles in motivating learners (Keller, 1987). Having choices based on their interests and a supportive community that fosters collaboration provide linguistic support for emergent ELLs and DLLs. Social learning can be fun and playful. Students learn while discovering and playing. Leverage nature, creative opportunities, and teamwork in learning. Incorporate art, music, movement, theater, dance, play, discovery, and building. Children are naturally inquisitive. Tap into that! Engage in dialogic reading outdoors in nature! Let children express themselves through painting, drawing, pretend-play, and makerspace experiences to form hypotheses, test them, and develop their own interpretations of the world. As an ILA Literacy Brief suggests, children are active constructors of meaning. Let them play, discover, and learn!

Translanguaging

For DLLs, welcome translanguaging in their two languages. The use of both languages is an expression of their bicultural and bilingual identity. Translanguaging is very common and natural for non-native speakers of English who speak more than one language.

Here is a brief synopsis of some effective strategies (Hayes et al., 1998) that you can implement in your classroom:

- Rebus is a very useful strategy that ensures that students have more than one way of expression by using a combination of pictures and writing to communicate meaning.

- Idioms are culturally specific expressions, so much so that even after years of living in the U.S., some idioms can still be hard to understand, especially if they are connected to a culturally specific local context or sports which newcomers or immigrants might be unfamiliar with, for example, “knee-high by the Fourth of July” – an Iowa-specific idiom referring to the hoped-for corn growth. Idioms are important to understanding dialogue, so teaching them to ELLs through illustrations and the relevant background information is essential. Have the children follow this pattern:

- State the idiom.

- Illustrate the idiom.

- Provide the literal meaning of the words.

- State the cultural context and significance. Provide the actual meaning.

- Illustrate the vocabulary – “Sketch to stretch.” Drawing the vocabulary words communicates meaning. In addition, ELLs can act them out; they can write synonyms, antonyms, and put the words in sentences.

- Dialogue journaling is a conversation that happens between the teacher and the student. This has been shown to build relationships, and it is helpful to students for them to have access to the teacher when they are going through the transition to a new culture.

- Create a story using wordless picturebooks. Use picturebooks to leverage ELLs’ background knowledge and cultural capital to make meaning while reading and writing stories. This activity also develops oral language.

- Writing Weird Recipes with bugs and insects is a lot of fun for kids! Make a dish using the class recipe.

- Do collaborative writing where one child describes an alien and another one draws it.

- Have the children collect some interesting items on a nature walk and describe them to a peer. What can you do with the object?

- Write a play or reader’s theater with a peer with dialogues and enact it in class.

- Have the children write a poem or a song from their culture and teach it to others.

- Implement guided reading groups to differentiate instruction for ELLs with varying levels of English and first-language proficiency.

- Engage in a Global Goals project. Choose one of the sustainable Global Goals and engage in researching it as a small group. Collaborate with another classroom from another part of the world!

Lastly, ensure that you create an inclusive space where other countries, cultures, and people are not stereotyped. The video below shows us the importance of not judging any child or their family based on a single story. It is key for the teacher to provide multicultural, diverse literature that provides mirrors where children can see themselves and windows and sliding doors that widen children’s perspective of other cultures (Sims Bishop, 1990).

- What is the essence of this video?

- Discuss the quotes that resonated with you and why? What implications do they have for your future classroom?

Dyslexia

“Dyslexia is a specific learning disability that is neurobiological in origin. It is characterized by difficulties with accurate and/or fluent word recognition and by poor spelling and decoding abilities. These difficulties typically result from a deficit in the phonological component of language that is often unexpected in relation to other cognitive abilities and the provision of effective classroom instruction. Secondary consequences may include problems in reading comprehension and reduced reading experience that can impede growth of vocabulary and background knowledge.”

As you learned in the chapter on phonics, the National Reading Panel found that many difficulties encountered in learning to read were caused by poor phonemic awareness, and that systematic and explicit instruction in phonemic awareness contributed directly to improvements in children’s reading and spelling skills.

The following list shows common ways young children may show that they have difficulty “breaking the code”:

- Difficulty hearing or producing rhymes.

- Difficulty remembering or naming letter names and sounds.

- Inability to sound out known words.

- Slow, effortful oral reading.

- Misreading or omitting common short words.

- Inconsistent sight-word recognition.

- Difficulty remembering simple sequences such as reciting the alphabet, counting to 20, or naming the months of the year.

Dyslexia is NOT a visual problem with confusing letters; rather, it is a difficulty in processing the sounds of language. In other words, children don’t confuse b and d because they look alike; they confuse them because they sound alike.

However, young children often confuse letters, so letter reversal alone is insufficient to signal an underlying problem. If you notice a child who struggles with any of these tasks, it is essential to document the areas of difficulty.

Keep in mind that people have only been reading for a few hundred years. Our brains were not developed to read – rather they are designed to recognize language and objects. So having difficulty reading is not an indication that someone is not intelligent – in fact, many people with reading difficulties are very talented! It is a problem with the way the brain processes the sounds of language. Brain research [YouTube video] demonstrates that people with dyslexia rely too much on their memory, neglecting to use the faster system of sounding words out. However, research has also demonstrated that with training, the patterns can be changed. In other words, we can retrain the brain to use the sound system.

Early intervention is key! The earlier we can recognize the signs of a possible reading difficulty, the earlier systematic instruction can begin.

In the next video, a parent discusses how difficult it was to get help for her child who was struggling with reading. What were the signs of reading problems?

How to provide support

First, if you have documented that a student has trouble in the areas listed above, talk with your schools’ Special Education staff about a referral.

However, you can support the student in your classroom. The first thing you can do is to develop a positive, supportive relationship with the student. A review of close to 150 studies on motivation found that to help children succeed, you must help them feel 3 things:

- Competent: A feeling of competence doesn’t mean that students already know how to do something, but that they have the confidence that they’re capable of learning it. Starting off a reading lesson with something the students already know can build the feeling of competence. Then go to something that might be harder and encourage them to try it.

- Belonging: This is feeling accepted and connected to others. Listen to a student’s thoughts and feelings and respond with empathy: “Yes, learning new things can be hard. I know what that feels like.” Help the student build the identities of a learner and a reader.

- Autonomy: This is about choices and deciding for yourself what you want to do. Even little choices make a difference. Let the student pick their own books and personalize their assignments. Explain the rules and requirements of lessons so that the students can understand why they’re being asked to do them.

These suggestions by the International Dyslexia Association (see Resources, pp.7-8) can help any student who might be struggling. These work for students who are learning English as a second or third language as well.

- Clarify and simplify written directions. Some directions are written in paragraph form and contain unnecessary information. These can be overwhelming to some students. The teacher can help by underlining or highlighting the significant parts of the directions. Rewriting the directions is also often helpful.

- When confronting unacceptable behavior, do not inadvertently discourage the child with dyslexia. Words such as “lazy” or “incorrigible” can seriously damage the child’s self-image.

- Present a small amount of work. The teacher can tear pages from workbooks and other materials to present small assignments to students who are anxious about the amount of work to be done. This technique prevents students from examining an entire workbook or other large amount of text and becoming discouraged.

- Block out extraneous stimuli. If a student is easily distracted by visual stimuli on a full worksheet or page, a blank sheet of paper can be used to cover sections of the page not being worked on at the time. Also, line markers can be used to aid reading, and windows can be used to display individual math problems. Additionally, using larger font sizes and increasing spacing can help separate sections.

- Provide additional practice activities. Some materials do not provide enough practice activities for students with learning problems to acquire mastery of selected skills. Teachers then must supplement the material with practice activities. Recommended practice exercises include instructional games, peer-teaching activities, self-correcting materials, computer software programs, and additional worksheets.

- Use assistive technology. Products such as tablets, electronic readers/dictionaries/spellers, text-to-speech programs, audio books, and more can be very useful tools.

- Employ peer-mediated learning. The teacher can pair peers of different ability levels to review their notes, study for a test, read aloud to each other, write stories, or conduct laboratory experiments. Also, a partner can read math problems for students with reading problems to solve.

- Make work times flexible. Students who work slowly may be given additional time to complete written assignments.

- Provide additional practice. Students require different amounts of practice to master skills or content, and students with learning problems need ample practice.

Adverse childhood experiences and trauma-informed instruction

ACEs, or adverse childhood experiences, are traumatic events that can dramatically upset a child’s sense of safety and well-being. These experiences can include substance abuse in the home, the death of a parent, divorce, abuse, or witnessing violence. We know in our state that 64% of Iowans have experienced at least 1 ACE (Iowa ACES 360). Data from the 2016 National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH) showed that 46% of America’s children had experienced at least one adverse childhood experience, with the number rising to 55 percent for children aged 12 to 17. One in five U.S. children had had two or more ACEs.

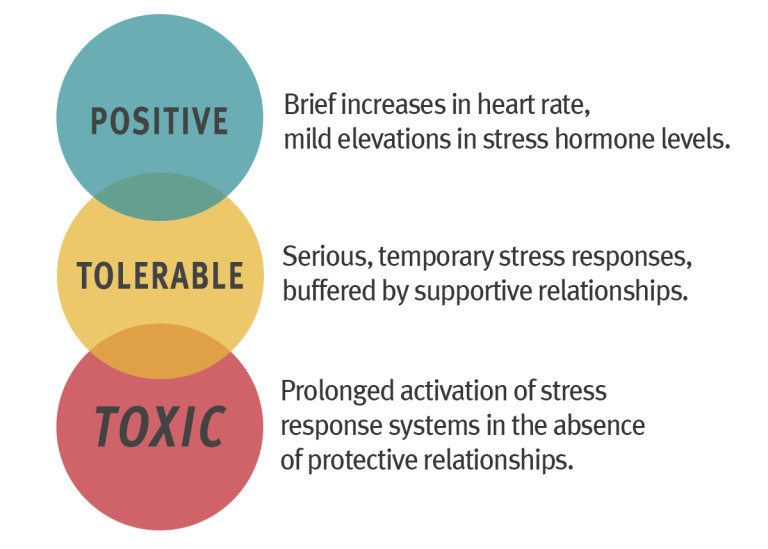

When we are threatened by stressful events, our body’s stress system kicks in to prepare us to respond by increasing our heart rate, blood pressure, and stress hormones such as cortisol. But not all stress is created equal. Some, as in the top circle, gets our heart pumping a little faster and slightly elevates our stress hormones, but it’s considered positive stress because it gets us moving to do something we need to or want to do. For example, maybe you are chatting with your spouse or friend when you realize how late it is getting. The stress of realizing that time before class is short gets you motivated to meet your goal of being on time to class.

The next level of stress is tolerable stress, shown in the yellow circle. This is a serious, but temporary stress that’s buffered by supportive relationships. Think about goodbyes between a parent and their child in your classroom in the morning. These can be highly stressful for both the child and their parent, but with support from you – a warm welcoming smile to the parent, a hug and engaging activities for the child – the stress is tolerable.

Toxic stress, the red circle, is prolonged stress. The biological stress response – what naturally happens in the body in stress situations – stays engaged, and in this case there are few, if any, protective relationships to buffer that stress. With toxic stress, the body just doesn’t get a break. Adverse Childhood Experiences from abuse, neglect, dysfunctional households, and violent situations can cause children to experience toxic stress.

How can a teacher recognize when a student might have experienced trauma? The signs can include:

- not following or understanding directions;

- overreacting to statements or events in the classroom;

- interpreting comments as negative;

- lack of understanding of cause and effect;

- poor communication skills; and

- difficulty in regulating emotions.

![]() Download this trauma toolkit for educators [PDF]

Download this trauma toolkit for educators [PDF]

The following recommendations for supporting students’ social emotional learning are drawn from the Trauma Toolkit: Tools to support the Learning and Development of Students Experiencing Childhood & Adolescent Trauma, by First Book:

- Create a safe classroom environment. Incorporating consistent routines and rituals in the classroom helps students experience predictability and security. Take a zero-tolerance stance on bullying, teasing, and other behaviors that make children feel unsafe or threatened.

- Help students identify an area of competence. Whether it is an academic subject, extracurricular activity, or other creative outlet, helping students identify an area where they feel successful is important to their healing and development.

- Develop rapport and positive relationships with students. Students experiencing trauma greatly benefit from having strong, positive relationships with adults and peers.

The Responsive Classroom

An evidence-based program that helps to build positive relationships in the classroom is “The Responsive Classroom.” Here are the basic components of the Responsive Classroom approach:

Shared practices (K–8)

- Interactive modeling: an explicit practice for teaching procedures and routines (such as those for entering and exiting the room), as well as academic and social skills (such as engaging with the text or giving and accepting feedback).

- Teacher language: the intentional use of language to enable students to engage in their learning and develop the academic, social, and emotional skills they need to be successful in and out of school.

- Logical consequences: a non-punitive response to misbehavior that allows teachers to set clear limits and students to fix and learn from their mistakes while maintaining their dignity.

- Interactive learning structures: purposeful activities that give students opportunities to engage with content in active (hands-on) and interactive (social) ways.

Elementary practices (K–6)

- Morning meeting: Everyone in the classroom gathers in a circle for twenty to thirty minutes at the beginning of each school day and proceeds through four sequential components: greeting, sharing, group activity, and morning message.

- Establishing rules: The teacher and students work together to name individual goals for the year and establish rules that will help everyone reach those goals.

- Energizers: short, playful, whole-group activities that are used as breaks in lessons.

- Quiet time: a brief, purposeful, and relaxed time of transition that takes place after lunch and recess, before the rest of the school day continues.

- Closing circle: five to ten minutes at the end of the day in which everyone participates in a brief activity that promotes reflection and celebration.

You can read more about the principles and practices on the Responsive Classroom website.

While the teacher can support students with practices like these, remember that if you suspect trauma or abuse, you should follow your school’s policies on reporting and seeking help for children.

- This chapter has covered how to support many different types of students, but the main takeaway should be that each student has a right to receive a quality education with a teacher who cares.

- When teachers take time to form relationships with students and their caregivers, teachers can better serve the students in their class.

Resources for teacher educators

- The Influence of Home on School Success

- Learning for Justice

- 6 Essential Strategies for Teaching English Language Learners

- 12 Ways to Support English Learners in the Mainstream Classroom | Cult of Pedagogy

- Innovative strategies for teaching English language learners | UMass Global

- eLearning – Online Literacy Professional Development (module on Dyslexia)

- What is Dyslexia?: An Overview for Educators [Powerpoint slides] provides general information about dyslexia from Iowa’s Area Education Agencies (AEA).

References

Barshay, J (2021). Proof points: What almost 150 studies say about how to motivate students. PROOF POINTS: What almost 150 studies say about how to motivate students – The Hechinger Report

Bartlett, J. D., Smith, S., & Bringewatt, E. (2017). Helping young children who have experienced trauma: Policies and strategies for early care and education. https://academiccommons.columbia.edu/doi/10.7916/d8-f1gn-7n98

Botelho, M. J., & Rudman, M. K. (2009). Critical multicultural analysis of children’s literature: Mirrors, windows, and doors. New York, NY: Routledge.

Cai, M. (2002). Multicultural literature for children and young adults. Greenwood Press.

CDC. (2019). Fast Facts: Preventing adverse childhood experiences. Retrieved https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/aces/fastfact.html

De La Peña, M. (2015). Last stop on Market street (C. Robinson, Illus.).The Penguin Group.

Hayes, C., Bahruth, R., & Kessler, C. (1998). Literacy con carino. Heinmann.

Iowa Area Education Agencies (n.d.) Iowa Dyslexia Resources. https://sites.google.com/a/heartlandaea.org/dyslexia-resources/additional-resources?authuser=0#h.p_f4d16xk6z91m

Keller, J.M. (1987). Development and use of the ARCS model of instructional design. Journal of Instructional Development 10 (3), 2-10. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02905780

Krashen, S. (1981). Second language acquisition and second language learning. Prentice-Hall.

Sims Bishop, R. (1992). Multicultural literature for children: Making informed choices. In V. J. Harris (Ed.), Teaching multicultural literature in grades K-8 (pp.37-54). Christopher-Gordon.

Sims Bishop, R. (1990). Mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors. Perspectives: Choosing and Using Books for the Classroom, 6(3), ix-xi.

Quast, E., & Bazemore-Bertrand, S. (2019). Exploring economic diversity and inequity through picturebooks. The Reading Teacher, 73(2), 219-222.

Wherry, J. H. (2004). The influence of home on school success. PRINCIPAL-ARLINGTON-, 84(1), 6-7.

Williams, J.M. & Scherrer, K. (2017). Trauma toolkit: Tools to support the learning and development of students experiencing childhood & adolescent trauma. First Book.

Young, T. A., Bryan, G., Jacobs, J. S., & Tunnel, M. O. (2020). Children’s literature, briefly (7th ed.). Pearson.