Chapter 8. Writing

Nandita Gurjar and Sohyun Meacham

“I can shake off everything as I write, my sorrows disappear, my courage is reborn.” – Anne Frank

Keywords: writing development, writing process, writing workshop, prewriting, drafting, revising, editing, mentor text, mini lessons, writing strategies, conferring

Iowa Core Standards for Writing

Kindergarten

- Use a combination of drawing, dictating, and writing to compose opinion pieces in which they tell a reader the topic or the name of the book they are writing about and state an opinion or preference about the topic or book (e.g., My favorite book is…).

- Use a combination of drawing, dictating, and writing to compose informative/explanatory texts in which they name what they are writing about and supply some information about the topic.

- Use a combination of drawing, dictating, and writing to narrate a single event or several loosely linked events, tell about the events in the order in which they occurred, and provide a reaction to what happened.

- With guidance and support from adults, respond to questions and suggestions from peers and add details to strengthen writing as needed.

- With guidance and support from adults, explore a variety of digital tools to produce and publish writing, including in collaboration with peers.

- Participate in shared research and writing projects (e.g., explore a number of books by a favorite author and express opinions about them).

- With guidance and support from adults, recall information from experiences or gather information from provided sources to answer a question.

First Grade

- Write opinion pieces in which they introduce the topic or name the book they are writing about, state an opinion, supply a reason for the opinion, and provide some sense of closure. (W.1.1)

- Write informative/explanatory texts in which they name a topic, supply some facts about the topic, and provide some sense of closure. (W.1.2)

- Write narratives in which they recount two or more appropriately sequenced events, include some details regarding what happened, use temporal words to signal event order, and provide some sense of closure. (W.1.3)

- With guidance and support from adults, focus on a topic, respond to questions and suggestions from peers, and add details to strengthen writing as needed. (W.1.5)

- With guidance and support from adults, use a variety of digital tools to produce and publish writing, including in collaboration with peers. (W.1.6)

- Participate in shared research and writing projects (e.g., explore a number of “how-to” books on a given topic and use them to write a sequence of instructions). (W.1.7)

- With guidance and support from adults, recall information from experiences or gather information from provided sources to answer a question. (W.1.8)

Second Grade

- Write opinion pieces in which they introduce the topic or book they are writing about, state an opinion, supply reasons that support the opinion, use linking words (e.g., because, and, also) to connect opinion and reasons, and provide a concluding statement or section.

- Write informative/explanatory texts in which they introduce a topic, use facts and definitions to develop points, and provide a concluding statement or section.

- Write narratives in which they recount a well-elaborated event or short sequence of events, include details to describe actions, thoughts, and feelings, use temporal words to signal event order, and provide a sense of closure.

- With guidance and support from adults and peers, focus on a topic and strengthen writing as needed by revising and editing.

- With guidance and support from adults, use a variety of digital tools to produce and publish writing, including in collaboration with peers.

- Participate in shared research and writing projects (e.g., read a number of books on a single topic to produce a report; record science observations).

- Recall information from experiences or gather information from provided sources to answer a question.

Imagine you are in a kindergarten classroom, and the children are in a writing workshop. You look around the room. Some kids are drawing a concrete or shape poem on a whiteboard; others can be seen telling a story to a volunteer; some are writing down their ideas in a graphic organizer, while others are working on grabbers or creating a lead to capture audience attention. The teacher moves from student to student, conferring with them and teaching specific skills they need, differentiating their instruction. This demonstrates the beauty of the writing workshop, where everyone works productively at their own pace while the teacher scaffolds and supports the students as they write, revise, edit, and work on formatting and publishing their work.

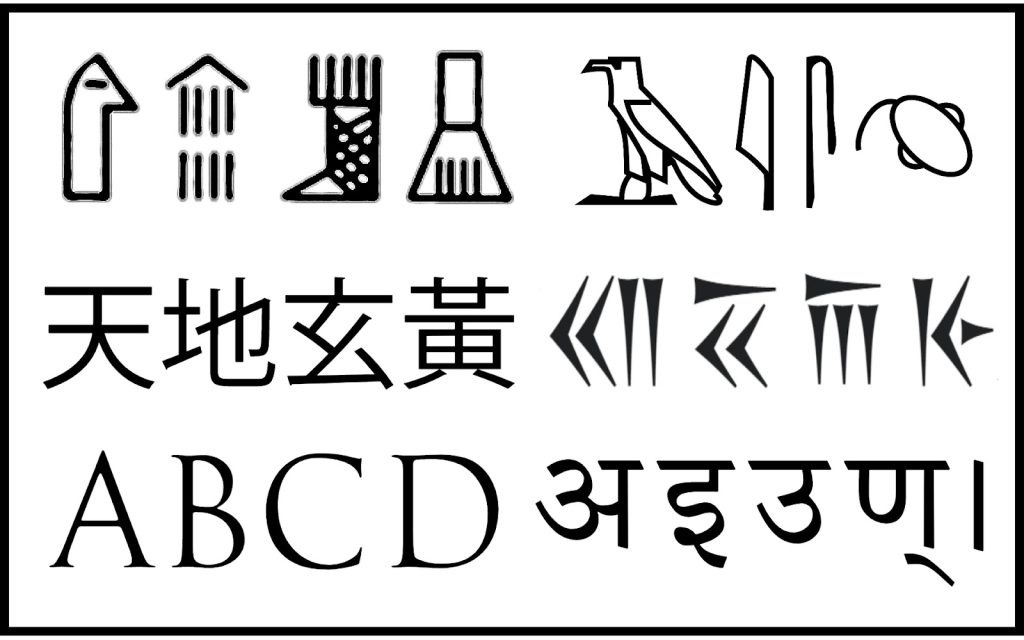

Children’s writing development

Reading and writing develop simultaneously. Marie Clay, a “guru” of young children’s literacy development, suggests that writing can be encouraged if your child can just hold a pencil or a crayon. They do not need to master reading first for you to teach them writing. In the early stages of children’s writing development, they just draw and scribble. Research has found that very young children who can’t write yet can distinguish between drawing and “writing.” When they say they are drawing, they make large figures with round edges. When they say they are writing, though, they use strokes and dots. They lift their pencil off the page and interrupt their movements more when they are “writing.” Just be patient when you see your child scribbling indiscernible letters. When they scribble and call it writing, just affirm them and encourage them to do more “writing.”

Your child will go through several different stages in the process of writing development. Their scribbles will turn into letter-like forms arranged linearly. Then when there are real noticeable letters in your child’s writing, it still might be pretend writing with randomly ordered letters. Some letter combinations could represent correct sound blends. Many times, these are letters from your child’s name or are used at the beginning of words. It is a long journey for your children to master the conventional English writing system. In the meantime, allow them to use their own inventive spelling. “It is far too soon to aim for correctness. Accept and enjoy the child’s many attempts and accomplishments” (Clay, 2010, p. 12).

Gentry’s (2005) writing-development scale can track children’s writing progress and personalize instruction to scaffold their writing development. It describes 5 stages that children go through. Van Ness et al. (2013, p. 578) provide Gentry’s writing-development stages as listed below:

- Non-alphabetic: Children use markings, scribbles, and pictures, but no letters.

- Pre-alphabetic: Children write letters, but the letters do not represent sounds. Random letters cannot be read, for example, “RzxTQO” for “bottle.”

- Partial alphabetic: Children write letters that represent sounds. There is directionality such as from left to right. There is some correct spelling, for example, “bt” for “bottle.”

- Full alphabetic: Children provide a letter for each sound. Some medial short vowels are written, for example, “botl” for “bottle.”

- Consolidated alphabetic: Most (two thirds) of the words are written correctly. There is one-to-one spelling correspondence, for example, “bottle” for “bottle.”

Spelling as a window into child’s reading and writing development

Spelling is a window through which you can assess your child’s reading development (Bear, Invernizzi, Templeton, & Johnston, 2019). When your child is only able to pretend to read, their writing looks like scribbles. When they start using letter-sound knowledge and blending letters, they might get the beginning and ending consonants, while omitting the intervening vowels, for instance, spelling cat as ct. Once vowels are used correctly in simple words like cat and dog, your child will start learning to spell more complicated words. At this stage, bottle might be spelled botl. English is one of the most opaque languages in terms of spelling. That is why you can see many English monolingual adults who still struggle with it. Much reading experience is necessary for your children to learn to spell correctly, in addition to their receiving explicit teaching of spelling patterns in words. We suggest graciously accepting developmental spelling, also known as invented spelling, in children’s writing to encourage them to focus on the content of their writing as they go through Gentry’s developmental stages of writing.

Developing an author identity in children

There are wordless and nearly wordless picturebooks that can provide a context for your child to write something meaningful and useful. Since the illustrations in the book is open to each child’s unique interpretation, you can suggest that your child become the author for the picturebook by creating their own story. You can have a conversation with your child as you examine the illustrations together. Then you can encourage your child to write their story based on your conversation.

Louie and Sierschynski (2015, p. 110) provided neatly structured steps to follow when it comes to teaching writing to children with wordless picturebooks.

- First, preview the peritextual features: the cover, title page, end pages, dedication and author’s note.

- Second, use repeated viewings to help them identify the elements in layers, such as setting, text structure, and characters.

- Third, analyze the author’s purpose together by asking your children why the author/illustrator uses certain images.

- Fourth, help the children put your discussion in writing, by choosing a text structure such as description, comparing & contrasting, cause & effect, problem & solution, sequence, or a story map as a retelling guide.

Louie and Sierschynski’s steps were originally developed as a writing-instruction strategy for learners of English as a second language in the classroom. However, they work well for any family with English as a first or second language. If your children can still only write a few words, and not sentences or paragraphs, you can still encourage them to write some words for a wordless picturebook. Making a road sign or writing a few words in a bubble for a character is a good start. Crews’ Truck is a wordless picturebook. Wherever the red truck goes, Crews illustrates details of the vehicles, roads, and landscapes surrounding it, including some signs as environmental prints (common logos that the children will be familiar with). Adding more road signs in Truck would be a fun writing project for your children.

Many adults only think about the grammar, spelling, and mechanics of writing. However, as you see from Louie and Sierschynski’s strategy above, text structure is an important starting point for writing that your child must learn to be a good writer. In addition, other perspectives from which you can analyze your child’s writing are ideas, organization, voice, word choice, sentence fluency, conventions, and presentation. This list is the “6 + 1 traits of writing” framework. It was originally 6 traits, and the last trait (presentation) was added to evaluate how the sentences and paragraphs are presented on a page or online screen. As you can see here, writing is so much more than grammar and mechanics. Especially when your child is just starting to write, rather than focusing on grammar and mechanics, listen to your child tell the story that they are trying to write. This can support their process of developing the content of the story. If your child covers a piece of paper with drawings and a couple of letters, try to decipher it with your child.

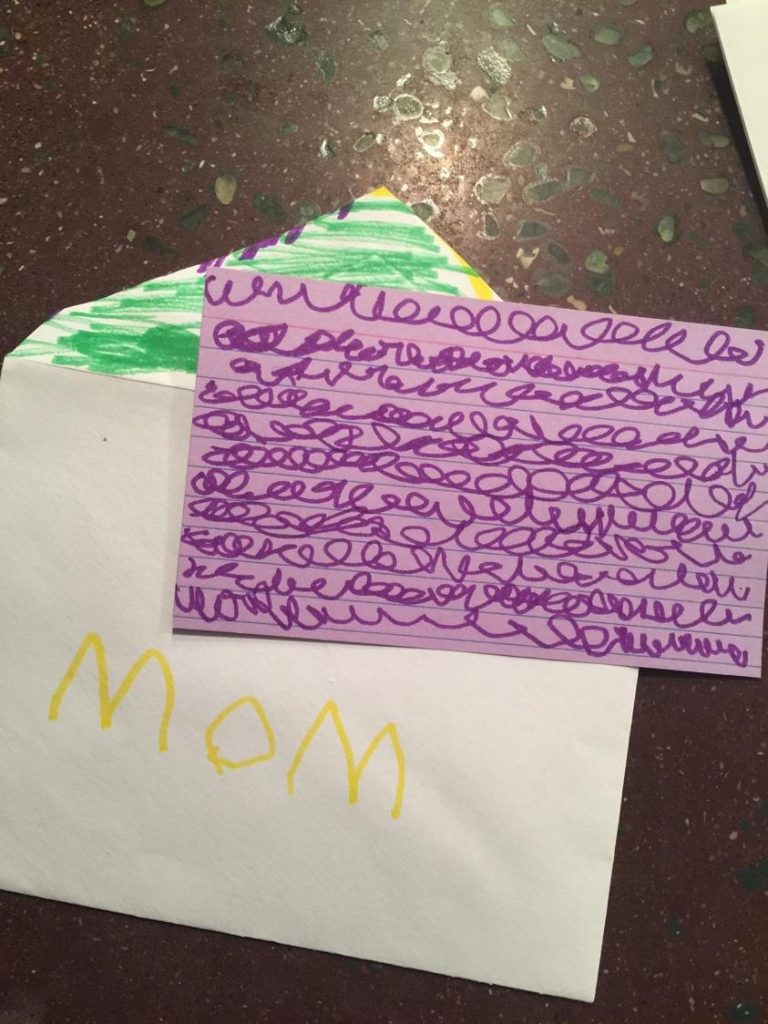

Let’s say your child shows you a small card with squiggly lines and “MOM” on the back. Your face shows much excitement. You ask your child, “Wow, is this card for me? Did you write a card for me?” Then your child will explain what they wrote for you. Oral language and written language work together for you here to understand what your child is trying to communicate. Apparently, the main idea of that writing is love for Mom.

It is important for your child to be able to identify themselves as an author in everyday life. At some point, they might feel that writing is something required only for schoolwork. However, writing is not just for book authors and journalists. Writing can be fun and useful in everyday life. There are many authentic purposes, like writing letters to loved ones and special occasion cards to friends. Your child needs to perceive purposes of writing like these and develop an author identity. The earlier they see the big picture, the less they will struggle with writing at school.

Soh’s daughter has loved writing in Bare Books since she was able to write some words on her own, although her spelling was predominantly inventive. Bare Books are blank books with hard white covers and white pages. They usually contain 32 pages that your child can write on, following the average traditional picturebook page count. She has written several of her own books. One titled Fireman had a problem for the main character, a fireman, to solve: putting out a fire. She recalls writing this book below:

“When I was on a trip to Arizona, I was working on a book called Fireman. It’s a realistic fiction book about a few firemen that saw fire in New York City, at the Empire State Building. It took quite a while for me to get done with the problems. So they had to spray water out of the hose a lot. Multiple times! A lot of kids like firemen. I think they will enjoy my Fireman book. The reason I got inspired to write the book is because I went to a firehouse.”

She is a third grader now, but she calls herself an author. She always engages in writing at home for her own authentic purposes, not only for homework. She wants to be a veterinarian when she grows up. She says she can still be an author while she takes care of ill animals for her job.

There are children who are reluctant writers. If your child likes watching videos, you can use them as a springboard for your child’s writing. Strassman and O’Connell (2007) suggested this strategy:

“Authoring with Video (AWV) enables students to get started writing in a medium they know and love: video. It is similar to writing text for a wordless picturebook. The videos, like the pictures in a wordless book, serve as the trigger for an organized text. Finding their voices as writers is less of a challenge for students because they are comfortable with messages and visual images working together to communicate meaning. AWV encourages students to formally recognize this ability as a skill that has its roots in writing. It capitalizes on the sophisticated video-viewing and comprehension abilities of children and casts them as writers, publishers, and producers of content.” (Strassman & O’Connell, 2007, p.330)

The important thing is to promote your child’s writing habit and support their development of an author identity. All the fun pieces written by your author-child for you to enjoy reading are just the entertaining by products!

Schickedanz and Collins (2013, pp. 124-125) recommend the following effective practices for supporting children in their writing:

- Read to children even in infancy and engage them in conversation. It not only develops language, vocabulary, and their background knowledge, but also makes them familiar with written discourse.

- Expose them to a range of purposes for writing in daily life such as creating a menu, compiling a grocery list, writing a note to their mom, making a wish list for Santa, etc.

- Provide mark-making experiences (scribbles, mock letters, and pictures) early, as it gives an opportunity for them to talk about the meaning.

- Talk to children about their writing and drawing.

- Keep the focus on meaning and communicating.

Using wordless picturebooks to promote writing for dual-language learners

I (Nandita) enjoy using wordless picturebooks in my undergraduate and graduate classes. Writing with wordless picturebooks not only ignites imagination and creativity (among the top-ten skills based on a WEF report) but also supports collaboration, which makes writing fun and engaging! Laughter fills my room as the students joyfully share their whimsical stories.

Every semester, I hunt local public libraries and the university library to find unique, new wordless picturebooks. My college students get a kick out of collaborating to create fresh, original stories inspired by the ideas and imaginations of each individual in the group. It is fun for them to share their creative stories with their peers! The purpose of this exercise is for the preservice teachers to pass this joyful learning experience with wordless picturebooks on to their elementary students, who may come from various backgrounds and cultural contexts.

Wordless picturebooks build a schema for the story with the narrative elements of setting, characters, plot, and theme. They can be used to promote language development as the adult asks critical thinking questions to encourage the children to “view” the text closely and construct meaning. The pictures provide visual scaffolding for building vocabulary and language skills, providing comprehensible input for dual-language learners.

Dual-language learners bring their own cultural experiences as they interpret the visuals and create an authentic, personally meaningful story. These stories can be published and shared in a celebration of learning with music, games, and food, where the parents are invited to the school, and the children get to showcase and proudly share their work. This learning celebration honors children’s cultural heritage (Leija & Peralta, 2020) and positively impacts children’s emerging identities. A positive self-concept builds positive self-esteem and a sense of belonging, fostering a safe learning environment. Validating, embracing, and welcoming children’s whole selves with their linguistic and cultural identities creates a nurturing environment conducive to their literacy development.

Our goals as writing teachers

- Have a consistent writing time every day.

- Provide choice, which develops voice in writing.

- Incorporate writing throughout the day.

- Create a safe learning environment to write and share.

- Support and honor children’s writing.

- Model writing, sharing, and celebrating writing.

- Provide authentic opportunities to write.

Authentic writing

Authentic writing aims to communicate to an authentic audience in children’s lives. An example of authentic writing is writing a letter to a grandmother, aunt, or other relative or friend. After reading the book Flat Stanley, my daughter’s classroom teacher had her write a letter to her aunt. In that letter, Flat Stanley was sent to Boston. The daughter requested the aunt to take him to museums and collect postcards from every place he visited. The aunt sent Flat Stanley back with a letter and postcards. This activity provided authentic reading and writing opportunities to strengthen the child’s literacy skills.

Working on project-based learning and global collaboration also facilitates authentic writing opportunities. For example, children may participate in global read-aloud and do related writing activities, or they may collaborate on global goals and read, write, create, and invent with peers to solve global problems for sustainable global goals.

Writing across content areas

Integrate writing in math, science, and social studies. Write research reports, create posters and advertisements, and compose using tools of technology to be creative communicators.

Daily journaling

One of the ways to incorporate daily writing is through daily journaling and “quick writes.” Brainstorm and generate a list of topics with children for journaling to give them a managed choice. Journaling is discussed more under personal narratives. Quick writes can be meaningfully integrated throughout the day to increase the volume of writing children do daily. It also develops a writing habit in children and gradually increases their focus and stamina in writing.

Some examples of quick writes are provided below.

Think-writes

“Think-Writes are short, quick bits of writing that help students focus and clarify their thinking” (Cunningham & Allington, 2016, p. 182). The audience for think-writes is only the writer. This writing is done in 2-5 minutes for the purpose of jotting down one’s thoughts or ideas.

Think-write-pair-share

Writing is thinking. Writing provides quiet time to gather thoughts and jot them down before talking. We may ask children to write or draw to represent their thinking and then talk to their “shoulder buddy” about their drawing or writing.

Exit tickets

Exit tickets may be done in a variety of ways. Children may illustrate a vocabulary word that they learned that day. They may complete the sentence: Today I learned _______________. Children may complete a graphic organizer in pairs under the guidance of an adult.

While some writing is quick writing for jotting down thoughts, other writing follows a process to create a product for sharing with an audience. The audience could be parents, peers, teachers, or others. The genre and format (letter, short story, opinion essay, poem, etc.) depend on the author’s purpose.

The writing process

Writing is not a linear process, but iterative and recursive in fashion. It consists of five stages:

Prewriting

According to Donald Murray (1985), 70% of the time should be spent prewriting. During prewriting, the focus is on identifying the topic, purpose, audience, and genre. The focus at this stage is on the content. It is better to allow a self-selected topic on which the child has background information. Donald Graves (1983) and Lucy Calkins (1994) have affirmed that choice brings out the voice in children’s writing, showing the author’s personality. Reading Rockets recommends the RAFT strategy of writing, which helps kids explore their role as a writer.

- Topic: The topic needs to be manageable and focused. It should not be too broad. The choice of the topic depends on the student, but it should be something they are interested in and have background knowledge on.

- Purpose: The children need to be made cognizant of why they are writing. What is the purpose of their writing? Is it to entertain, inform, or persuade?

- Audience: The choice of words and how a piece is written depends on the audience. A letter meant for a friend is different from one written to Mom. Consideration of the audience is very important for achieving appropriate and effective writing.

- Genre: The genre is carefully chosen to best attain the writer’s goal or purpose. For example, suppose the purpose of writing is to persuade – what genre of writing would best accomplish that purpose? Possible writing genres include a letter, essay, poem, song, infomercial, commercial, poster, tweet, video, short story, newspaper article, cartoon strip, play, blog, research report, and so on.

Generating and Synthesizing Ideas on a Graphic Organizer

Once the topic, purpose, audience, and genre are identified, focus on generating ideas. Mind-mapping tools and graphic organizers organize and synthesize ideas visually. This makes them great for ELLs due to their visual element. Kidspiration is a child-friendly mind-mapping app to display ideas. Children generate ideas by talking to peers, reading books, doing online research, and gathering pictures, audio, and video files for multimodal composing.

Drafting

The second stage of writing is drafting. The focus of drafting is on content creation and developing the ideas with elaboration and examples. The author works on developing a hook at the beginning of the piece. A hook or a grabber is something that will grab a reader’s attention and motivate them to read on. A mystery, humor, and a narrative can all act as grabbers that capture a reader’s attention. Craft a lead using mystery or humor, or inspire wonder, sympathy, anger, or fear in such a way that your audience will want to read your work (Forney, 2001).

Revising

Revising is different from editing. In revision, children re-read what they have written. They make their words and sentences clearer. They replace weak verbs with strong ones and include more vivid vocabulary, add details to their drawings and prose, move sentences and words, and delete anything that does not belong. The acronym ARMS accurately describes the revision process: children Add information, Remove information, Move words, phrases, and sentences, and Substitute words for more precise and interesting vocabulary. Then they re-read, question, ponder, share, and receive peer feedback. The goal of revision is clear and concise writing. Teachers may confer with students at this time.

Editing

Editing ensures that the spelling, punctuation, and grammar are correct. During editing, the mechanics and conventions are considered. The final writing should be readable and polished. The correct placement of punctuation such as commas ensures readability and flow. Proofreading is also done at this time to remove typos. Teachers can create editing circles and provide checklists for self-checking and peer-checking.

Publishing

The publishing process involves formatting, decorating, and getting binding done to create a published book to share with others. In the digital age, it is relatively easy to publish your work online. Kids blogs, Flipgrid videos, and eBooks have been created on various platforms. Little Bird Tales is for younger kids and combines pictures with the text to create a story. Bookcreator is another story-creation platform that can be used with guidance from adults.

Writing strategies for children

- Choose and narrow the topic. (What?)

- Set a purpose. (Why?)

- Consider the audience. (For whom?)

- Decide on the genre. (How?)

- Generate and organize ideas.

- Re-read, revise, elaborate, question, self-monitor, self-evaluate, share, and get peer feedback.

- Edit, proofread, format, and publish.

Things that strategic writers do:

- They make deliberate choices based on their purpose.

- They engage in self-regulation strategies such as self-monitoring and self-evaluating.

- They are willing to take feedback from peers and adults.

- Initially, they focus on developing the content, postponing looking for errors until towards the end.

Types of writing

Narrative writing

Narrative writing is story writing containing the elements of setting, characters, plot, and theme. The story can be based on personal experiences, as in the case of personal narratives, or they can be fictional stories written using imagination and creativity.

Personal narratives

Personal narratives are about personal experiences, and they convey the point of view of the author. Some of them, such as biographies and simulated journaling, convey the point of view of another individual the author has decided to write about.

Journal writing

Journaling is expressive writing. Incorporating journaling into your curriculum taps into the background experiences of the kids, and it functions as a connecting bridge between expressive writing and formal, academic, and transactional writing. I would suggest exploring children’s books written as journals at the developmentally appropriate level for the children. Daily journaling builds a positive attitude toward writing, where writing is seen as a medium for communicating ideas, processing life, and connecting with others. Through writing, thinking becomes visible.

Dialogue journals

Dialogue journaling is written dialogue that occurs between two individuals. It is a writing activity that builds positive, trusting relationships between the teacher and the students. It provides access to the teacher for the students and lets them share their thoughts and ask questions. When the teacher responds, the teacher’s writing provides authentic text that the students can read for meaning. The teacher’s writing also acts as a model of correct spelling and grammar for the students; this is especially valuable for dual-language learners.

Simulated journals

Simulated journals are a creative way for students to develop the point of view of an imaginary or real-life character by writing a journal while taking on the identity of that person.

Performance poetry or spoken-word poetry

Performance poetry is performed for an audience with voice and gestures to communicate an idea or theme. It develops civic agency in students to think about socio-cultural or environmental issues they are passionate about. Amanda Gordan and Sarah Kay are two well-known spoken-word poets. Performing poetry develops fluency in children as they learn to read with expression and conviction, using their voice and body as tools to convey ideas. Adults can help and guide children in writing poems and practicing their delivery.

Biographies

Children can read about their favorite historical or sports figures and write short biographies or bio poems of them.

Autobiographies

The children can write about themselves. In Literacy Con Carino, the children wrote the “autobiographies of not so famous people,” writing about themselves and envisioning their futures.

Fictional narratives

There are different strategies for inspiring story-writing in children. One effective way is to have them write a story, play, letter, or newspaper article that is prompted by a picture. For example, I have used the following picture for this purpose. Pictures spark creativity in writing. Students use their imagination to create a unique story. My students have come up with creative responses in the forms of poetry, a letter, a newspaper article, an eyewitness account, or a short story that is uniquely reflective of the author.

Cartoon strips

Cartoon strips are a lot of fun to write, as they focus on visuals more than words. The strips can be five frames long for starters.

Wordless picturebooks

Children who love to draw will enjoy creating a story by drawing a picture on each page. Adult guidance may be needed as the child plans and verbalizes the story’s beginning, middle, and end.

Short stories

The children can plan a story on a graphic organizer with a setting, characters, plot, and theme. They may leave some space at the top of the page for drawings and at the bottom for writing.

Fractured fairy tales

The children can tell a different version of the story from the point of view of another character through words and drawings. Then they can write that version of the fairy tale.

Children’s original endings

Coming up with their own endings to the story ignites creative thinking and imagination, and helps them understand the story better.

Plays

Pretend play makes it natural to write dialogues with quotation marks. The children may pair up with a buddy to create an imaginative scene out of their pretend play. After they write it, let them engage in pretend play with it to make it come alive.

Reader’s theater

Writing a reader’s theater script is like writing a play. In reader’s theater, the children read from a script they wrote. Reading and re-reading the script helps to build fluency.

Poetry writing

Poetry writing develops vocabulary and concise writing skills. Explore some poetry interactives at www.readwritethink.com

Limericks

A limerick is a rhyming poem with the “aa, bb, a” rhyme scheme. The first two lines rhyme; the third- and fourth lines rhyme, and the fifth line rhymes with the first two. Limericks can be written with a partner, taking turns coming up with words to match the rhyme scheme:

- Line 1: _______ a

- Line 2: _______ a

- Line 3: _______ b

- Line 4: _______ b

- Line 5: _______ a

Haikus

A haiku is a popular Japanese poem that has 3 lines. The first line has 5 syllables; the second has 7, and the last has 5. The children may write haikus on nature, the seasons, or any topic of their choice:

- Line 1: _______ (5 syllables)

- Line 2: _______ (7 syllables)

- Line 3: _______ (5 syllables)

Cinquains

A cinquain is a 5-line poem and follows the following structure:

- Line 1: _______ (a 1-word title)

- Line 2: _______, ______ (2 words describing the title)

- Line 3: _______, ______, ______ (3 words expressing a feeling)

- Line 4: _______, ______, ______, ______ (4 words expressing an action)

- Line 5: _______ (a synonym for the title or one word describing the title)

The children can write about their pets or their favorite sport or food.

Six-word memoirs

Six-word memoirs are great for motivating reluctant writers to write. They are short and simple, and the children only need to be motivated to write six words. An example of a six-word memoir is “I help my mom with chores!”

Diamantes

A diamante demonstrates opposites or antonyms. It is a 7-line diamond-shaped poem describing opposites:

- Line 1: ______ (noun)

- Line 2: ______, ______ (two describing words)

- Line 3: ______, ______, ______ (three words with “ing”)

- Line 4: ______, ______, ______, ______ (four words – two related to line 1, two related to line 7)

- Line 5: _______, ______, ______ (three words with “ing”)

- Line 6: _______, ______ (two describing words)

- Line 7: _______ (opposite noun)

Concrete or shape poems

Children draw a shape and then write phrases or sentences related to the drawing inside or around it. Shape poems are fun for children to create as it taps into their love for drawing and coloring.

Acrostic Poems

First the children choose a word or name, such as their own. Then they write it vertically going down, and each letter of the word is used to begin a descriptive word, phrase, or sentence. It makes for a great beginning-of-the-year activity for self-introductions. For example:

- N: Nice

- A: Amiable

- N: Nurturing

- D: Delightful

- I: Intelligent

- T: Teacher

- A: Attentive

Expository writing (nonfiction)

Informational writing

Informational writing conveys information to readers through recorded observations, interpretations, connections, research reports, processes, instructions, and problem solutions.

Science journals

In science journals, students make hypotheses, and write procedures, observations, and conclusions.

Double-entry journals

The double-entry journal is like a T-chart, where the child writes the main points on the left and comments on the right.

Math journals

Math journals can be used for solving word problems or other math-related problems.

Research reports

Children research a topic and write a detailed report on it.

ABC books on a country

An example of an ABC book is a research book on aspects of a country or culture. For example, if I were doing a book on India, I may have A for architecture, B for Bollywood movies, C for customs, D for traditions, E for elephants, F for food, and so on.

Recipes

Make writing playful and fun by coming up with weird recipes and fun names! Children enjoy bugs. Utilize their interests in developing recipes alongside them. Create a list of ingredients and develop a step-by-step process for preparing it.

Persuasive writing

Persuasive writing is done to persuade the readers to embrace a certain point of view or idea. To be convincing, the writer must provide strong reasons to support their assertions.

Newspaper articles

Some newspaper articles are written to persuade people about policies, programs, or procedures.

Letters

Letters can be written to persuade someone to take an action such as make a playground safer, improve the functionality of an old school building, address climate change, and so on.

Opinion writing

Opinion writing is a form of expository writing where students express their opinions on a choice of topics. Opinions are supported by evidence.

Children enjoy writing in the OREO format.

- O – State your opinion.

- R – Provide a reason. (Why?)

- E – Present evidence.

- O – Re-state the opinion.

Teachers engage the children in OREO writing by celebrating their writing with an OREO cookie party!

The writing workshop

Generally, writing workshops (Graham, 1983; Portalupi & Fletcher, 1995; Ray & Cleveland, 2004) are conducted anywhere from 45-60 minutes on a consistent basis to provide opportunities for students to write. Ray and Cleveland (2004) encourage free writing and drawing with younger students by providing them writing tools (chalk, shaving cream, finger paints, sand, modeling clay, etc.) of various kinds. This writing is supported by talk that focuses on communicating meaning, elaborating, and clarifying. Conferring with the children is very important throughout the writing process.

In the writing workshop, the teacher begins by first reading aloud the mentor’s text (Culham, 2014). The text exemplifies the features or a skill that the teacher is focusing on as a modeling example. Then, the teacher conducts a mini lesson that is usually 8-10 minutes long, and models with “I do” where she defines the feature or skill, explains how it is used, and shows an example. For example, in preschool, the teacher might demonstrate and provide a moving model for how to write “I.” She provides an example by using it in a sentence and asks the students to use it in a sentence also. Next, she continues guided practice with the students with “We do” and scaffolds their learning by checking for understanding. Lastly, she provides an opportunity for them to practice the skill independently with “you do,” while she watches and helps. Then the children brainstorm ideas, draft, craft leads, revise, edit, proofread, and publish their work. Writing circles (Vpat, 2009) are synonymous with literature circles, where students work collaboratively to write, revise, and publish. Providing a choice in writing (Calkins, 1994) and having a consistent writing time (Graves, 1983) support children’s writing development.

Conferring in the writing workshop

Student-teacher conferences in the writing workshop are an important method for supporting the students’ writing. Anderson (2019) notes: “Writing conferences help students become better writers. In conferences, students become known to us as people, writers, and learners. Through conferring, we become known to our students” (p. 10). While conferring, the teachers and students engage in purposeful talk (Hawkins, 2016) that scaffolds the students’ writing.

Conducting the student-teacher writing conference

Anderson (2019) suggests the following steps for conducting the writing conference:

- First, think about the logistics of conferring. Confer with the students at their own desks.

- Second, decide on the amount of time you will devote to each conference. Five-seven minutes is recommended.

- Confer with the students when they are still writing, and they will be more receptive to constructive feedback than when they are finished.

- Start the conferring process by asking the student an open-ended question – “How is it going?” – to see what the student is doing as a writer (Murray, 1985). Examine the student’s draft to assess the areas of strength and those needing growth.

- Decide on what to teach the student after assessing their draft.

- Provide positive feedback by focusing on what the child already understands and is doing well. Next, suggest the next step you would like the student to take to improve the writing.

- Explicitly teach a skill the student can apply to improve their writing. Provide modeling examples.

- Make your expectation clear that you would like the student to apply the skill that you just taught and that you will check back after you are done conferring with another student.

Benefits of conferring

- Conferring builds the student-teacher relationship. It sustains student motivation.

- Conferring is differentiated instruction, i.e., based on what the student needs.

- Conferring reinforces strategic writing: knowing the audience, choosing the topic and genre, crafting the writing, revising, and editing.

- Conferring informs whole-group instruction. Through conferring the teacher comes to know what most of the students are struggling with so they can revisit and reteach those concepts and skills.

Assessing writing with the 6+1 Traits Rubric (K-2 Rubric)

Please click on the hyperlink above to see the specific features we are looking for when evaluating a child’s writing. The 6+1 Traits of Writing (Culham, 2005) uses an analytical rubric that provides feedback on each area to inform instruction for strengthening the areas needing improvement.

Ideas

The goal here is to communicate clear, focused, well-developed ideas that are fresh and original through drawing, dictation, and writing. Our ideas for writing come from various sources, such as nature, personal experiences, books, videos, newspaper articles, and the people around us. Well-developed ideas are important in writing. One of the ways to assess writing is for the ideas and whether the child is communicating them well through writing, drawing, or dictation. Their writing also needs supporting details. Ideas need to be fresh and original, supported by details.

Organization

Good writing needs to be organized, with a grabber or hook, for an inviting start. It should be structured in paragraphs with topic sentences and supporting details, with smooth transitions between the paragraphs. The concluding paragraph needs to provide a strong finish.

Voice

Voice means it should sound like the person who has written it. The writing reflects the author’s personality and unique way of expression. The author conveys the feelings, mood, and awareness of the audience through their drawing and writing to connect with the readers. For example, Kwame Alexander writes novels in verse that is reminiscent of a shape or concrete poem. Authors’ personality often shines through in their writing. Providing choice brings out the writer’s voice, which makes the writing engaging, with humor, storytelling, or a unique way of presenting the content.

Word choice

The author chooses precise and vivid vocabulary from the wide range of words in their linguistic repertoire. Additionally, the author uses strong verbs that show how the action is performed instead of weak, overused verbs. For example, instead of look or see, the author uses glance, stare, gaze, and so on. Or, instead of walk, the author uses strut, hop, skip, swagger, skitter, and so on.

Sentence fluency

Is the child writing in sentences or not? Are the sentences decodable? What types of sentences are there in their writing? Sentence fluency reflects the cadence or rhythm of the language. The child enjoys reading aloud. There is variety in the sentence structures. There are dialogues and other sentence phrasing as needed to enhance the meaning. The punctuation marks are placed appropriately.

Conventions

Does the child display grade-level-appropriate knowledge of conventions such as punctuation, spelling, and grammar? Are they demonstrating skill in letter-sound relationships in their writing? Are they spelling conventionally or phonetically? Are most high-frequency words spelled correctly? Do they use periods, commas, question marks, and capital letters well? Where are they capitalizing?

Presentation

Presentation is important for the readability of the writing. Does the child have one finger space between words? Do they produce readable writing, with mostly correct letter formation, spacing, and the correct placement of drawings and other graphic elements about the writing? Is the handwriting polished and easy to read? Are the white spaces used well, and do all the elements contribute to clarifying the meaning?

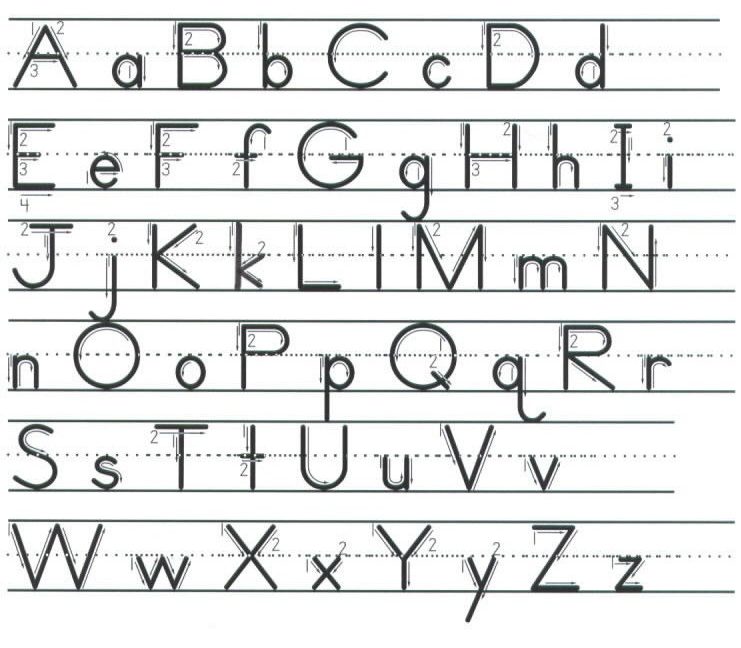

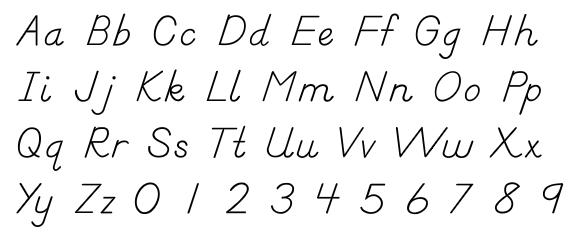

Penmanship

Handwriting is still pertinent even in the 21st century. There is a strong connection between the desire to communicate and growth in handwriting (Graves, 1983). Consistent time spent in meaningful writing with the freedom to choose the topic are the determining factors in the quality of handwriting (Graves, 1995).

There is evidence of a connection between the motor movement of writing and enhanced brain activity (Hannover Research Group, 2012). We remember more when we write by hand. When handwriting flows fluently, we think more cohesive thoughts.

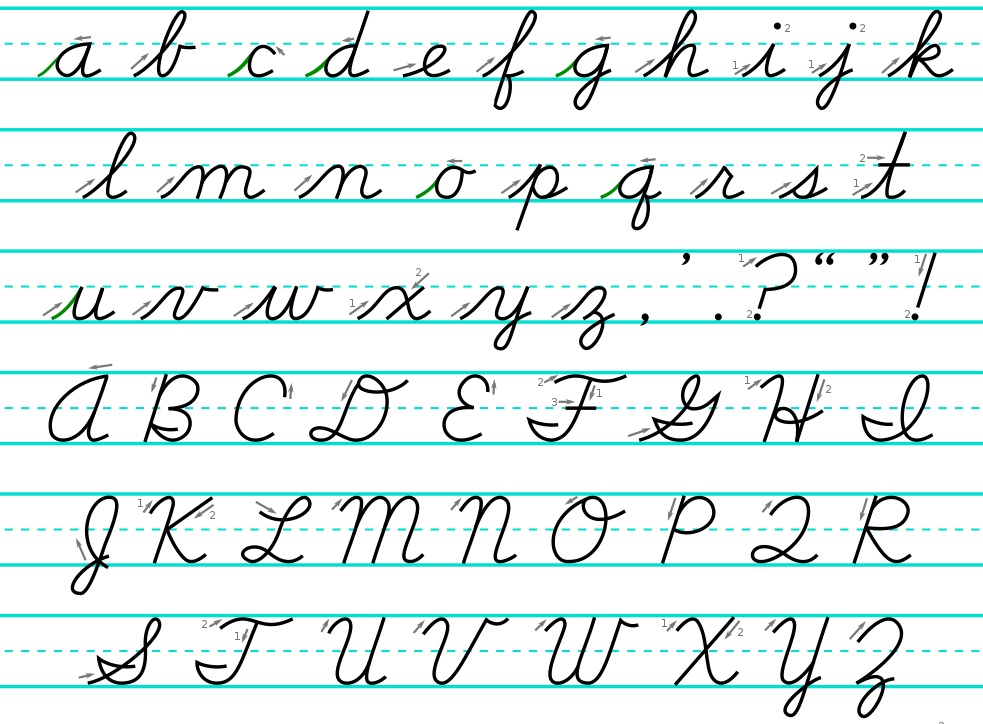

Handwriting is an essential skill for children to have. Teach children how to hold a pencil because once habits form, they are hard to break. Provide chunky pencils that are easier for young children to work with. Have a consistent time of at least 15 minutes to teach handwriting by providing a moving model while verbalizing your thinking as you form the letters. Manuscript and cursive writing are essential to teaching, even in the digital age.

As a teacher, you should have three goals when teaching handwriting to children: legibility, fluency (speed), and mechanics. Your method of instruction is to provide a moving model while verbalizing the process of forming letters, reminding them about size and proportion, spacing, consistency in the slant, alignment, symmetry, and line quality.

Elements of handwriting legibility

There are six elements of legibility in handwriting (Caravolas et al., 2020; Fogel et al., 2022), as explained below.

- Letter formation: Letter formation is the way the letters are constructed. Teachers model how to form each letter using three-lined paper. They demonstrate how to produce the letters as a moving model by making their thinking visible (think-aloud) while giving verbal instructions to the children.

- Size and proportion: The size and proportions of each letter are important for legibility. There should be a consistent size, and the parts of the letters should be in the right proportion to each other.

- Spacing: There should be a consistent rule for spacing. Generally, we tell young children to keep a one-finger space between words.

- Slant: The letters should be consistent for a neat and organized look.

- Alignment: The alignment and symmetry of the letters are components of legibility.

- Line quality: The lines used to form the letters need to be solid, not squiggly, for the writing to be neat and legible.

Forms of handwriting

Manuscript

D’Nealian

From D’Nealian to Cursive

Handwriting stations

Make handwriting fun with handwriting stations. Let them doodle when they have extra time! Make handwriting authentic and creative by supplying the stations with materials such as shaving cream, finger paints, sand, playdough, and so on.

Best practices in handwriting instruction

- Integrate handwriting in authentic writing contexts for science, social studies, math, and the writing workshop.

- Set aside time consistently (15-20 min.) to teach handwriting by providing a moving model and time to practice.

- The handwriting practice should be on a meaningful, open-ended prompt.

- Students self-evaluate their handwriting and set personalized goals.

- The goal of handwriting should always be legibility and not perfection.

- Portfolios that reflect growth over time are encouraged.

Adapting for diverse learners

- Incorporate Universal Design for Learning’s principles to remove perceivable barriers with multiple means of representation (video, visuals, audio, text, etc.); provide multiple means of engagement (learning pathways and experiences), and multiple means of expression, allowing the students to choose how to showcase their learning.

- Leverage students’ cultural and linguistic capital.

- Allow students to write in their native language.

- Incorporate Rebus or a combination of drawings and text.

- Use dialogue journaling to build relationships with all students.

- Use wordless picturebooks or visual prompts to inspire writing using students’ background knowledge.

- Create writing circles where each student contributes a line to construct a collaborative story.

- How can you motivate children to write?

- How can you engage children in authentic, fun writing experiences?

- How would you structure your classroom instruction to enhance the amount of writing children engage in daily?

Writing across the content areas

Create cross-curricular centers on a thematic topic for a grade level of your choice (K-2). Choose from one of the topics in the list provided. Please incorporate writing across content areas (science, social studies, and math) in an engaging way to motivate students to learn the content in depth.

Some themes to choose from:

- Places and Spaces (Iowa Core social studies topic for kindergarten)

- Community and Culture (Iowa Core social studies topic for 1st grade)

- Choices and Consequences (Iowa Core social studies topic for 2nd grade)

Digital storytelling

Create an eBook on a social-justice topic in a genre of your choice. You may use Bookcreator or any other tool to create a multimodal book. Think about your purpose, audience, topic, and genre. Gather or take pictures, record a short video, and explore multimodal resources to add visuals, texts, and hyperlinks.

- Provide a choice in writing.

- Choice brings out the writer’s voice.

- Graciously accept all forms of writing, including scribbles, mock letters, and pictures.

- Focus on meaning while conversing with the children about their writing.

- Have a consistent writing time.

- Confer with children.

- Read mentor texts aloud.

- Do mini lessons to teach specific skills.

- Differentiate instruction through the 6+1 traits of writing.

- Bring in writers’ cultural identities and heritage through culturally relevant prompts and read-alouds.

Resources for teacher educators

- Traits Rubric for K–2 | Education Northwest [PDF]

- Graphic Organizers to Help Kids With Writing | Reading Rockets

- Writing Reports in Kindergarten? Yes! | Read Write Think

- Seven great ways to encourage your child’s writing

- Composing multimodal writing with BookCreator

- Assessing Writing: Six Traits of Writing

- OER_Writing Process.pptx

- OER_ Self-Evaluation

References

Anderson, C. (2019). Let’s put conferring at the center of writing instruction. Voices from the Middle, 26(4), 9-13.

Bear, D. R., Invernizzi, M., Templeton, S., & Johnston, F. (2012). Words their way: Word study for phonics, vocabulary, and spelling instruction. Pearson.

Calkins, L. (1994). The art of teaching writing (New Ed.). Heinemann.

Caravolas, M., Downing, C., Hadden, C. L., & Wynne, C. (2020). Handwriting legibility and its relationship to spelling ability and age: Evidence from monolingual and bilingual children. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 10-97. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01097

Clay, M. (2010). How very young children explore writing. Heinemann.

Culham, R. (2005). 6+1 Traits of writing: A complete guide for the primary grades. Scholastic.

Culham, R. (2014). The writing thief: Using mentor texts to teach the craft of writing. International Reading Association.

Cunningham, P., & Allington, R. (2016). Classrooms that work: They can all read and write. Pearson.

Fletcher, R., & Portalupi, J. (2001). Writing workshop: The essential guide. Heinemann.

Fogel, Y., Rosenblum, S., & Barnett, A. L. (2022). Handwriting legibility across different writing tasks in school-aged children. Hong Kong Journal of Occupational Therapy, 35(1), 44–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/15691861221075709

Forney, M. (2001). Razzle, dazzle, writing: Achieving excellence through 50 target skills. Maupin House Publishing.

Gentry, J.R. (2005). Instructional techniques for emerging writers and special needs students at kindergarten and grade 1 levels. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 21(2), 113-134. doi:10.1080/10573560590915932

Graves, D. (1983). Writing: teachers and children at work. Heinemann.

Graves, D. (1995). A fresh look at writing. Heinemann.

Hanover Research Group (2012). The importance of teaching handwriting in the 21st century. Hanover Research Report, 2-11.

Hawkins, L. K. (2016). The power of purposeful talk in the primary-grade writing conference. Language Arts, 94(1), 8-21.

Leija, M.G., & Peralta, C. (2020). Día de los muertos: Opportunities to foster writing and reflect students’ cultural practices. The Reading Teacher, 73(4), 543-48. https://doi.org/10.1002/trtr.1871

Louie, B., & Sierschynski, J. (2015). Enhancing English learners’ language development using wordless picture books. The Reading Teacher 69(1)103-11.

Murray, D. (1985). A writer teaches writing. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Ray, K. W. & Cleveland, L.B. (2004). About the authors: Writing workshop with our youngest writers. Heinemann.

Schickedanz, J. A., & Collins, M. F. (2013). So much more than the ABCs: The early phases of reading and writing. National Association for the Early Childhood Education

Strassman, B. K. & O’Connell, T. (2007). Authoring with video. The Reading Teacher, 61(4), 330-333.

VanNess, A. R., Murnen, T. J., & Bertelsen, C.D. (2013). Let me tell you a secret: Kindergartners can write. The Reading Teacher, 66(7), 574-85.

Vpat, J. (2009). Writing circles: Kids revolutionize workshop. Heinemann.