1 Academic Veterinary Medical Libraries in the U.S. and Canada

Introduction

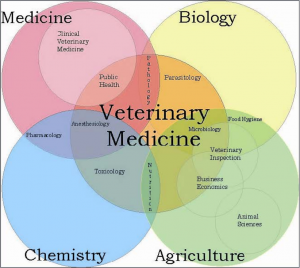

If you have ever watched circus animals perform, received a vaccine, eaten a piece of steak, or taken a pet to the clinic, you have been touched by the work of a veterinarian. Performing duties in animal welfare, medical research, food safety and clinical practice as they protect animal health and promote public health are primary obligations of the veterinary profession to society. Over 23,000 veterinary practices exist in the United States that employ an estimated 47,000 veterinarians who work in privately owned clinics. Public and corporate veterinarians add another almost 8,500 veterinarians who work in research and regulatory service.[1] A particularly excellent description is given by Gibb of the variety of veterinary duties, including engagement in private practice, academics, government, etc.[2] A depiction of the relationship of veterinary medicine to other scientific disciplines and agriculture is shown in Figure 1.

A number of books describe the history of veterinary medicine in some fashion, and that information does not need to be repeated here. Gibb, Oppong and Dunlop offer very fine chronologies into the evolution of veterinary medicine[3][4][5]. More recently, Judith Ho at the National Agricultural Library presents an extensive bibliography of historical resources.[6] Professor Dunlop’s book is especially noteworthy for his extensive description of the earliest veterinary literature, from the Egyptian Kahun Papyrus, dating to about 1900 BCE. The Chinese are credited with much of the early activity now known as veterinary medicine, this pertaining to care of military horses. Dunlop refers to the production of their veterinary literature, most of which dealt with horses, as beginning as early as 581 CE.

Today, veterinary professionals in North America are educated in universities that grant doctor of veterinary medicine degrees. Many of the earliest veterinary schools in the United States were private institutions that did not survive the vagaries of economic times. Unlike the governments of European nations, the United States government was not supportive of these schools. Other veterinary programs were outgrowths of curricula in veterinary science or agriculture at public colleges. Passage of the Morrill Acts of 1862 and 1890 ensured more stability for the teaching of veterinary medicine in the United States by establishing the land-grant colleges which considered it their duty to promote that profession. Iowa State College (University) was the first to open a state-supported veterinary school in 1879, with physical facilities that included a barn clinic and laboratory, a hospital, and a sanitary building. The 32 veterinary teaching institutions presently existing in the United States and Canada are, for the most part, separated by great geographic distances. Six schools are located in the western United States and Canada, 11 in the middle western states and provinces, eight in the eastern states and provinces, and seven in the southern United States.

Veterinary medicine is generally taught during four years of instruction. Post-doctoral education via internships and residencies may then be elected. Instruction begins with the pre-clinical sciences, such as physiology and pharmacology, which are then followed by the clinical sciences where a more problem oriented approach is taken as case work is integrated into the curriculum. In recent years, evidence-based medicine has made its debut into some veterinary instruction programs, thus enhancing the exposure of those students to the role of information resources and services.

Veterinary medical libraries evolved with the profession to try to answer its information needs in all of its capacities. While this evolution is sparsely documented in many cases, when found, documentation relates an array of dispersed veterinary collections, the struggle to find common space for materials, and the appropriate expertise to manage them. Gibb notes, “Specialist veterinary libraries or collections are few in number and most are in veterinary schools or run by national organizations”.[7] The concept of a veterinary medical library being an adjunct to veterinary education was not fully realized until the 1960s. Fadenrecht’s 1964 article entitled “Library Facilities and Practices in Colleges of Veterinary Medicine” quotes the American Veterinary Medical Association’s (AVMA) 1962 annual directory as saying that a library should be established as part of a veterinary school, as it is essential to a sound program of veterinary medical education.[8] At that time, according to Bigland, “more and more emphasis was being placed on the library as a source of information, learning and research, particularly in the veterinary colleges of the United States where research programs were expanding”.[9] The quote goes on to say that a professionally trained librarian should administer the library. In 1970 the AVMA again voiced its general guidelines for what it thought a library should have in order to meet its accreditation requirements:

The library should be established as a part of the veterinary medical school; it should be well-housed, conveniently located, and available for the use of students and faculty at all reasonable hours. It should be administered by a professionally trained or experienced librarian and should be adequately sustained both for operation and for the purchase of current periodicals and other accessions of veterinary medical importance. [10]

The Veterinary Medical Library Section of the Medical Library Association appointed a standards committee in May of 2000 to “create standards for the ideal academic veterinary medical library, written from the perspective of veterinary medical librarians”. They include a statement of need for the library’s collection in support of programs at the veterinary medical institution (including the need for interlibrary cooperation), and for the services that will be necessary for these programs. Other statements of need in the document address space requirements, and, in order to assure the library’s success, the necessity of a healthy administrative structure that is attuned to the needs of the library.

Today in the United States and Canada, veterinary medical libraries provide services and collections that support primarily teaching, clinical applications and research at colleges of veterinary medicine. They also serve students, faculty and staff of other academic subject disciplines on campus that interact with veterinary medicine, primarily the fields of agriculture, biological sciences, human medicine, nursing and pharmacy. They are state and national research resources because of their unique collections. They support the bibliographic needs of state and federal diagnostic laboratories, federal research laboratories, agricultural experiment stations and independent veterinary practitioners. The last group has been a particularly problematic one since this group has information needs that span all veterinary sub-specialties while often practicing in areas remote to veterinary libraries.

The 2000/2001 Survey of Veterinary Medical Libraries in the United States and Canada, issued by the Veterinary Medical Libraries Section of the Medical Library Association, groups veterinary medical libraries by their physical type:

Group 1: A separate library that serves primarily the faculty, staff, and students of school/colleges of veterinary medicine. This is the most common situation.

Group 2: Separate locations for the veterinary collections—a campus library and a clinical library.

Group 3: A separate library unit that serves two or more curricula, including veterinary medicine. These are usually the largest libraries in the survey and include medical, agricultural and general university library collections.[11]

Most of the Group 1 libraries range in size between 6,500 and 8,500 square feet of available space. The clinical library in Group 2 is typically smaller, while those in Group 3 are much larger.

Among the many categories of data reported in this survey is the composition of the user groups of some of these libraries. For the twenty-one libraries reporting for the category “Number of Primary Clients” during that year, the summarized data shows:

Veterinary Medicine Faculty: 2,867

Medicine Faculty: 589

Veterinary Medical Students: 7,936

Medical Students: 1,261

Veterinary Medical Graduate Students: 1,590

Medical Graduate Students: 245

“Other” Graduate Students: 250

Smaller numbers of pharmacy, nursing, agriculture and “Other” faculty and students are also reported in the survey. Gate counts for the majority of the Group 1 libraries that reported ranged between about 39,000 and 56,000 per year. All Group 3 reporting libraries tallied over 70,000 users, as did two libraries in Group 1, and one of the libraries in Group 2.

According to the survey results and the hours posted at the various Web sites of the libraries, the number of hours that the libraries are open to provide on-site services ranged from the low 80s to around 100 hours per week. Services that are offered during these hours include on-site reference assistance, literature searches, document delivery, loan of materials and interlibrary loan service. Access to online catalogs, electronic full text journals, and World Wide Web sites is typically available whether or not the library is open.

Evolution of some veterinary medical libraries

Cornell University

The AVMA Directory (2002) gives a short description of the inception of veterinary medical education at Cornell University in 1868. Dr. James Law (of Edinburgh, Scotland) became the first professor of veterinary medicine at an American university.[12] New York State Governor Roswell P. Flower formally signed legislation to the New York State Veterinary College at Cornell University in 1894. A fascinating account of the evolution of the Cornell veterinary medical library, written by Suzanne K. Whitaker, veterinary medical librarian from 1978–1998, appears online.[13] She relates that although two rooms were allotted to a library, there were no books or other materials available to place there. One of the first professional veterinary medical librarians, Atha Louise Henley, noted in her historical accounting of the VML Section of the Medical Library Association that “Often, our holdings of veterinary medicine and related sources on medical specialties and comparative medicine had been the textbooks and private collections of early deans and faculty members of institutions.”[14] She goes on to say that in 1897 the then ex-governor Flower of New York state seized the opportunity to donate $5,000 towards the purchase of materials for the library. “By 1901, 304 bound volumes along with unbound works, pamphlets, and water color illustrations had been purchased with $4000 of the Governor’s gift.” The library’s first full-time librarian was appointed in 1923. According to Whitaker, the library was expanded or relocated several times before its current location in the Veterinary Education Center building, with over 18,000 square feet of space assigned to the library as reported in the 2000/2001 Veterinary Medical Library Section survey.[15] The library Web site lists the collection holdings as of June 30, 2003 as over 100,000 bound volumes, over 800 serial subscriptions and about 1600 audiovisual titles.

University of Pennsylvania

The University of Pennsylvania’s School of Veterinary Medicine was established in 1883 and opened in 1884. According to John E. Martin’s A Legacy and a Promise—University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine, the first written reference to a formal library facility appears in the 1913 Veterinary School Bulletin. “Prior to 1913 documents mention a reading room that also functioned as a library.”[16] In what becomes a familiar refrain when reading about early veterinary libraries, they go on to say that most of the books were contributed by the faculty. At this time the library is described as being located in the corner of one of the veterinary buildings and as having a part-time librarian in Dr. Victor G. Kimball, an instructor in veterinary medicine. The library was not part of the University of Pennsylvania’s library system. It would not have its own full-time librarian until 1942 when sufficient donated funds had been secured to support an expanded library. The library went from on initial 2800 volumes to 8,000 by 1944 according to Martin. In what was ascribed to a change in veterinary school teaching methods towards “self-learning,” use of the library was moved to a new building in 1964. The library had become a part of the University Library system, with full service offerings beyond housing and circulation.

Washington State University

The professional veterinary school at then Washington State College opened in 1899. From Peter Harriman and Ghery D. Pettit’s book about the College of Veterinary Medicine at Washington State, First Century: A Centennial History, published in 1998, we learn that:

A proposal for a new veterinary medical library was developed in 1962. It was originally to have been built on the lawn between Wegner and McCoy Halls. WSU hoped to secure a National Institutes of Health grant for the estimated $227,000 construction and wanted to have it completed by 1964. Instead, the library was established in a 7,700-square-foot addition to Wegner Hall. When Wegner Hall was gutted and doubled in size in 1980 so the VCAPP Department could share the building with the College of Pharmacy, the library was enlarged again. It presently has more than 60,000 volumes and serves 85,000 patrons annually. In April 1990, librarian Vicki Croft became a Distinguished Member of the Medical Library Association, its highest level of certification.[17]

Online “History and Focus” information speaks to the merging of the pharmaceutical and veterinary medical collections to “serve the needs of not only WSU campus patrons and practicing veterinarians, but also pharmacists and clinical pharmacologists.”[18] That was followed by transfer of medical and nursing journals from the science library to the veterinary medical/pharmacy library in 2000, and a subsequent renaming of the library to “Health Sciences Library” to reflect the broader focus of the library. The 2000/2001 Veterinary Medical Library Section survey lists total volumes of the library at just over 72,000.[19]

Colorado State University

Following the inception of a department of veterinary science in 1883, the professional veterinary program became one of the earliest veterinary schools to be established in the western United States in 1907. At the time, the Colorado Agriculture College library was housed in the same building as the veterinary laboratory which, according to Teri Switzer, was apparently quite odiferous.[20] The collection of veterinary materials was described by Switzer as being “meager,” but was greatly expanded when the Veterinary Medical Association used proceeds from the sale of textbooks to purchase more veterinary books for the library. Switzer goes on to say that “By 1912 the Veterinary Science Department held one of the best ‘strictly veterinary’ libraries in the United States.” When a new veterinary building became a reality in 1979, space was allotted for the Veterinary Teaching Hospital Branch Library through a memorandum of understanding between the deans of the library and of the college of veterinary medicine. Switzer recounts that the collection of veterinary books grew from 950 in 1980 to nearly 2000 in 1991, and that journal subscriptions doubled in that time span. Online information about the library shows a collection size of approximately 10,000 volumes and 161 serial subscriptions.[21]

Texas A&M University

Texas A&M University opened its School of Veterinary Medicine in 1916 with thirteen students. Patton W. Burns tells us in Veterinary Medicine at Texas A & M University 1958–1975 that “The veterinary library was opened in September of 1949 with an inventory of 533 books and 678 bound periodicals with limited space in the southwest corner of Veterinary Medicine Building.”[22] It employed a graduate librarian. From 1949 on, a library committee was appointed annually by the Dean of Veterinary Medicine that was comprised of veterinary faculty and the librarian. The library outgrew the initial space and in 1968 was awarded “a central and prominent location of the first floor of the Veterinary Administration Building [with] approximately 10,000 square feet of floor space.” He describes the Veterinary Medical Library as being part of the University Library system with housing, furnishings and equipment supplied by the College of Veterinary Medicine. The library, now named the Medical Sciences Library, currently also serves professional medical faculty and students, in approximately 44,000 square feet of space, with holdings of over 120,000 print volumes and 1,600 serials according to its Web site.[23]

University of Illinois

As with many of the earlier schools, the University of Illinois offered courses in veterinary medicine well before the first class of students began receiving instruction in the newly authorized College of Veterinary Medicine in 1948. Online historical information informs us that prior to the formal opening of a veterinary medical library in 1952 when the new Veterinary Medicine Building was completed, books covering the topic of veterinary medicine were housed in various buildings around the campus.[24] At that time the library consisted of a single room of about 2700 square feet. Books and journals were relocated to the new library, which, according to the website, has been staffed with a librarian and support staff since its opening. In 1982 the library was relocated to more than 10,000 square feet of space in the Veterinary Medicine Basic Science Building, and, according to the library’s Web home page, as of 1998 holds over 47,000 volumes (including monographs, bound periodicals, video tapes and theses). The library’s mission statement says that “The collection and the services of the Veterinary Medicine Library are primarily intended to support the teaching, research, and public service activities of the College of Veterinary Medicine as well as those in related departments across campus”.[25]

Tuskegee University

A few pages are devoted to the founding of the Tuskegee University School of Veterinary Medicine’s library in veterinary Professor and Associate Dean Eugene W. Adam’s historical accounting of that veterinary school. He noted that “there was no formal library facility in the School of Veterinary Medicine during its first years.”[26] However, the AVMA’s Council on Education inspection team in 1949 urged that a reading room for veterinary materials be established. In a 1965 report, this room was subsequently described as being small, with unclassified materials, and lacking any staff attending to it. Adam’s goes on to say that “It was not until 1967 when Mrs. Frances Davis, (BS, MLS), the first qualified librarian, was assigned to the School of Veterinary Medicine Reading Room, that a formal connection was established with the Central Library.” During the 1970’s improvements to library resources and services were made that brought the library to a full service status that met student needs and the accreditation requirements of the AVMA. The library’s Web home page describes the current library as being located in the School of Veterinary Medicine complex, with holdings of about 31,000 volumes (including monographs, bound serials, and microfilm).

Iowa State University

Knowledge of the evolution of the veterinary library at Iowa State University comes to us through Sara R. Peterson who documented its beginnings in an article published in the Bulletin of the Medical Library Association in 1979, and through file records at the library.[27] The file records relate that veterinary courses were first offered to senior class agriculture students in 1872. Subsequently, in 1879, under the direction of Dr. Millikan Stalker, the School of Veterinary Science was founded, offering a two-year program. Dr. John Thomson, 14th Dean of the college, said that “A founding premise of the college was to provide a scientific method and organization to the control of animal diseases, helping to ensure the success of the food animal industry.”[28] The program was extended to three years in 1887, then to four years in 1903. According to the file records, “early physical facilities included a barn that served as a clinic and laboratory, a veterinary hospital and the Sanitary Building.” A Veterinary Medical Quadrangle was constructed in 1912, housing the College of Veterinary Medicine, along with space for a library. The collection at that time served the Departments of Zoology and Bacteriology as well as the College of Veterinary Medicine. The records say that the first librarian, Agnes Flemming, was not hired until 1915. Peterson quotes the 1917 Iowa State College catalog as listing 2600 volumes and 100 technical journals and farm papers in the collection. However, this collection was incorporated into the central university library collection in 1925 when a new building for it was opened. Apparently need was felt by the veterinary students to have a few of their own specialized materials available at the Veterinary Quadrangle, and in 1943, a student gift fund was established to purchase books for this purpose. Ms. Peterson was hired in 1971 to coordinate plans for a new library, acting on the recommendations of Ann Elizabeth Kerker, veterinary medical librarian at Purdue University, who in 1968 was consulted by Warren B. Kuhn, the Dean of Library Services, and Dr. Ralph Kitchell, the Dean of the Veterinary College about establishing a strong veterinary collection to be housed in new College of Veterinary Medicine facilities. These new facilities were opened for student use in the fall of 1976. As a typical Group 1 library (a separate or branch library that serves primarily the faculty, staff and students of schools/colleges of veterinary medicine), this library currently serves approximately 150 veterinary medical faculty, 400 veterinary medical professional students, and 85 graduate students in a 6631 square foot facility within the College of Veterinary Medicine. The home page link in electronic format is https://web.archive.org/web/20060207122233/http://www.lib.iastate.edu/services1/branch/vet_links.html.

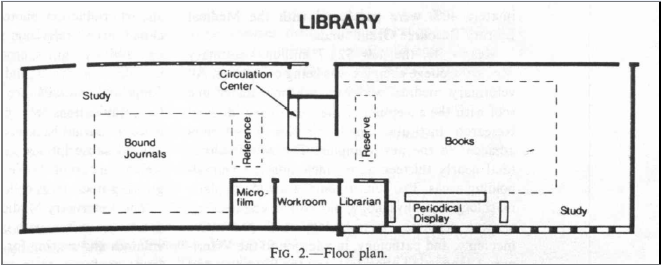

One professional librarian, two paraprofessionals and 2 students provide services at various times during the 83.5 hours that the library is open to users. The library maintains a collection of approximately 34,000 volumes and 700 periodical titles in print. Its holdings are primarily in veterinary science and the related subjects of comparative and human medicine, animal science, and zoology. The collection is divided into two major parts, separated by the Service Desk: journals on one side of the room and books on the other (Figure 2). Both books and journals are arranged by Library of Congress call number. Many journals, books, and indexes are now accessible from the library’s website. Journal articles, book chapters, and index citations can be viewed from the computer screen, printed, or downloaded.

Western College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Saskatchewan

In the fall of 1963 the Western College of Veterinary Medicine was established to serve the needs of the four western Canadian provinces. Dr. Christopher Hedley Bigland, VS, DVM, DVPH, MSc, MRCVs, DSc, wrote an engaging section describing the inception of the veterinary library in his book about the history of the Western College of Veterinary Medicine (WCVM).[29] The Ontario Veterinary College, which is one of the oldest in North American (having been established in 1862) had a library that Bigland describes in the 1940s as being typical for the times. It consisted of a few outdated books and a few journals, with “no librarian and no encouragement to read the current literature.” He reports that at the time of establishment of the WCVM in 1963 for four years of professional study, interest in a veterinary library was high. Space for such a library, though small, was allotted. Bigland describes the area as comprised of two rooms with two small tables, four chairs, and shelving. The University of Saskatchewan already had an established system branch libraries, with each having a trained librarian to administer it. The first veterinary medical librarian, a Mrs. Martin, arranged for the transfer of veterinary books and journals from other libraries in the system to the VML. Dr. Bigland describes this as a “great step forward for the faculty to be able to take a spare half hour from their very busy planning schedule to leaf through some of the current journals.” The idea for a “Friends of the WCVM” was incepted by a Calgary practitioner and other Alberta veterinarians as a means of donating funds for library purchases. Veterinarians throughout western Canada donated funds which were then matched by a Calgary philanthropist. According to Bigland, by the time of the Colleges’ official opening in July of 1969, these funds helped procure back journals, books and equipment for a two story facility in the new veterinary college. He reports that by 1979, the library consisted of 150,000 books, and about 650 journals and that “the WCVM library was considered by many to be one of the best veterinary libraries in the world.” According to the library’s Web home page, its collection consists of holdings in veterinary medicine, toxicology and animal science in print format and increasingly in CD-ROM and networked products.[30] The 2000/2001 survey done by the Veterinary Medical Libraries Section reports a 2,250 square foot facility with study seating of 85 and specialized seating of 13; monograph volumes numbering about 21,000 and 18,000 journal volumes from a total of 392 serial titles.

Louisiana State University

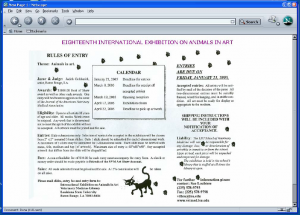

Instruction for the first class of veterinary students at the Louisiana State University (LSU) School of Veterinary Medicine began in January of 1974. In a more ordered manner than has been seen with the evolution of previously described veterinary libraries, development of the LSU veterinary library began the year following authorization by the LSU Board of Supervisors for a veterinary school in 1968. According to veterinary librarian Sue Loubiere, both library and veterinary personnel were involved in the planning for physical design as well as in the early development of the collection.[31] In an unusual circumstance, the professional librarian was appointed as a veterinary faculty school member in 1974, while the library itself was administered by the Director of the LSU Library. This relationship ended in 1978 when a new veterinary medicine building was completed, and included 7400 square feet of space for the library. Administratively, the library reports to the School of Veterinary Medicine, and functions autonomously from the LSU university library. Loubiere states that the “SVM Library has become the primary source for health science materials in the Baton Rouge area.” The library’s Web home page lists current holdings of approximately 45,000 volumes and 6,000 current periodicals covering the subject areas of veterinary and medicine, as well as some materials in related areas such as the animal sciences, comparative medicine and public health.[32] The library is also well known as the site of an annual juried art exhibition held by the School of Veterinary Medicine. Entries are submitted by artists from throughout the United States and, occasionally, the world.

Evolution of the veterinary medical library section of the Medical Library Association

An informative narrative of the history of the evolution of the Veterinary Medical Libraries Section of Medical Library Association (MLA) appears at the MLANET Web site.[33] According to the Web site a “Committee to Investigate the Possibility of Writing a History of the Section” was appointed in 1987. It was charged with removing the Section’s archives from the possession of past or present Chair of the Section to a more formal home under the purview of an appointed archivist who would be responsible for collecting and maintaining the chapters archival materials. Altha Louise Henley, a veterinary medical librarian at Auburn University Libraries from 1970–1983, became the Section’s first archivist in 1989. Her historical accounting comprises a substantial part of the section’s history found at the website. She relates the actions of several pioneering veterinary medical librarians in the 1960s and 1970s who educated others in the medical and library professions to “the importance of veterinary medicine as a vital part of medicine.” According to Henley, this was accomplished in part by their scholarly publications and in other ways, such as lobbying the MLA for recognition as a section. As increasing numbers of veterinary medical librarians participated in informal gatherings at the annual MLA annual meetings, she relates that support was born for the establishment of such a group. Formal approval came from the MLA board in 1973. Ann Elizabeth Kerker, Purdue veterinary medical librarian, and subsequent president of the MLA (1975–76), is accorded much of the credit for the inception of this section. According to the MLANET Web site, the stated purpose of the group was:

- to stimulate and foster interest in veterinary medical libraries and librarianship;

- to acquaint persons interested in veterinary medical libraries and librarianship with the Association;

- to encourage development of and cooperation among veterinary medical libraries, and;

- to foster a forum for the exchange of ideas and the discussion of mutual problems and concerns.

Henley’s accounting relates that important organization recognition was garnered from the National Library of Medicine and the National Agricultural Library, which supported the group through employee participation at the group’s meetings and cooperative projects. The AVMA and the Commonwealth Agricultural Bureau (CAB) also supported the group in many ways, including the AVMA’s regular publication of information about veterinary libraries with their services in their annual Directory, and through presentations by AVMA and CAB members at the group’s annual meetings. Now formally called the Veterinary Medical Libraries Section, this group of approximately 75 members (in 2005) is active with programming at the MLA annual meeting that frequently includes tours of zoos and other animal facilities around the nation. They maintain an electronic mailing list, VETLIB-L that is available to members worldwide, and a twice yearly newsletter called Highlights & News Notes, both of which are used for networking, and for sharing resources and expertise.

- American Veterinary Medical Association. "U.S. Veterinarians." Veterinary Market Statistics. Updated January 2006. https://web.archive.org/web/20060207014819/http://www.avma.org:80/membshp/marketstats/usvets.asp. ↵

- Mike Gibb, Keyguide to information resources in veterinary medicine (London: Mansell Pub, 1990). ↵

- Gibb, Keyguide. ↵

- E. N. W. Oppong, Veterinary Medicine in the Service of Mankind (Accra: Ghana Academy of Arts and Sciences, 1998). ↵

- R. H. Dunlop. Veterinary Medicine: An Illustrated History (St. Louis: Mosby, 1995). ↵

- Judith Ho. "Information Resources on Veterinary History at the National Agricultural Library." Animal Welfare Information Center. Published February 2005. https://web.archive.org/web/20060210102851/http://www.nal.usda.gov:80/awic/pubs/VetHistory/vethistory.htm. ↵

- Gibb, Keyguide. ↵

- George H. Fedenrecht, "Library Facilities and Practices in Colleges of Veterinary Medicine," College & Research Libraries 25 (1964), 308–316, 335. ↵

- Christopher Hedley Bigland, WCVM—The First Decade and More. The History of the Western College of Veterinary Medicine (Saskatoon: Western College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Saskatchewan, 1990). ↵

- Committee on Veterinary Medical Research and Education, National Research Council, New horizons for veterinary medicine (Washington, D. C.: National Academy of Sciences, 1972). ↵

- Survey Committee of the Veterinary Medical Libraries Section of the Medical Library Association, Survey of Veterinary Medical Libraries in the United States and Canada 2000/2001, (Blacksburg: Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, 2002), https://web.archive.org/web/20070329000717/http://www.lib.vt.edu/services/branches/vetmed/VMLS/2000-2001%20Survey%20Results.pdf. ↵

- American Veterinary Medical Association, AVMA Directory and Resource Manual (Schaumburg, IL: American Veterinary Medical Association, 2002). ↵

- Suzanne K. Whitaker, "Veterinary Library Overview and History," Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine, https://web.archive.org/web/20100824213908/http://www.vet.cornell.edu:80/library/overview.htm. ↵

- Atha Louise Henley, Kathrine MacNeil, and Gretchen Stephens. "The Veterinary Medical Libraries Section of the Medical Library Association: 1972–1998," MLANet, February 1, 1999, https://web.archive.org/web/20060116131259/http://www.mlanet.org:80/about/history/unit-history/veterinary.html. ↵

- Survey Committee, 2002. ↵

- John E. Martin, A Legacy and a Promise: The First One Hundred Years, 1994–1994 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 1984). ↵

- Peter Harriman and Ghery Pettit. The First Century: A Centennial History (Pullman, Washington State University, 1998). ↵

- Washington State University Health Sciences Library, "About Us," https://web.archive.org/web/20060220204412/http://www.wsulibs.wsu.edu:80/hsl/about.htm#history ↵

- Committee on Veterinary Medical Research and Education, 1972. ↵

- Teri Switzer, "Colorado State University's Veterinary Teaching Hospital Branch Library: Eighty Years in the Making," Colorado Libraries 17 (1991): 36–38. ↵

- Colorado State University Libraries, Veterinary Teaching Hospital Branch Library, "About Our Collection," Updated May 24, 2004, https://web.archive.org/web/20060228041646/http://lib.colostate.edu:80/branches/vet/about.html. ↵

- Patton W. Burns, Veterinary Medicine at Texas A&M University, 1958–1975 (College Station: Texas A&M University College of Veterinary Medicine, 1976). ↵

- Texas A&M University Libraries, "Medical Services Library," https://web.archive.org/web/20050303225037/http://ednetold.tamu.edu:80/vgn/portal/tamulib/content/renderer/0,2174,1724_17562,00.html. ↵

- University of Illinois Veterinary Medicine Library, "History," updated on October 15, 2002, https://web.archive.org/web/20060216122702/http://www.library.uiuc.edu:80/vex/vetdocs/history.htm. ↵

- University of Illinois Veterinary Medicine Library, "Mission Statement," updated April 2, 1999, https://web.archive.org/web/20050313130345/http://www.library.uiuc.edu:80/vex/vetdocs/mission.htm. ↵

- Eugene W. Adams, The Legacy: A history of the Tuskegee University School of Veterinary Medicine (Tuskegee, AL: Media Center Press, 1995). ↵

- Sara R. Peterson, "Evolution of a Veterinary Medical Library," Bulletin of the Medical Library Association 67 (1979): 36–41. ↵

- Iowa State University, "Iowa State's College of Veterinary Medicine Celebrates 125th Anniversary," News Service, April 7, 2005, https://web.archive.org/web/20151004021736/http://www.public.iastate.edu/~nscentral/news/2005/apr/anniversary.shtml. ↵

- Christopher Hedley Bigland, WCVM—The First Decade and More: The History of the Western College of Veterinary Medicine (Saskatoon: Western College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Saskatchewan, 1990. ↵

- University of Saskatchewan Veterinary Medicine Library, "Collections," https://web.archive.org/web/20060503072501/http://library.usask.ca:80/vetmed/collections.htm. ↵

- Sue Loubiere, "Louisiana State University School of Veterinary Medicine Library," LLA Bulletin 48 (1986): 145–147. ↵

- Louisiana State University School of Veterinary Medicine, "Veterinary Medicine Library," revised March 27, 2005, https://web.archive.org/web/20051122040615/http://www.vetmed.lsu.edu:80/library/vetlib/coll.htm. ↵

- Henley, MacNeil, and Stephens, "The Veterinary Medical Libraries Section." ↵