Chapter 7. Fluency and Comprehension

Nandita Gurjar

“Some books are so familiar that reading them is like being home again” – Louisa May Alcott in Little Women

Keywords: word recognition, re-reading, predicting, summarizing, self-monitoring, think-aloud, echo reading, choral reading, shared reading, guided reading, read-aloud, partner reading, recorded reading, word walls, readers’ theater

Comprehension: Kindergarten standards

Key details

- With prompting and support, ask and answer questions about the key details in a text.

- With prompting and support, retell familiar stories, including key details.

- With prompting and support, identify characters, settings, and major events in a story.

Craft and structure

- Ask and answer questions about unknown words in a text.

- Recognize common types of texts (e.g., storybooks, poems).

- With prompting and support, name the author and illustrator of a story and define the role of each in telling the story.

Integration of knowledge and ideas

- With prompting and support, describe the relationship between illustrations and the story in which they appear (e.g., what moment in a story an illustration depicts).

- With prompting and support, compare and contrast the adventures and experiences of characters in familiar stories.

Range of reading and text complexity

- Actively engage in group reading activities with purpose and understanding.

- For other grade-level comprehension standards, see Iowa’s standards here.

Fluency

Kindergarten

- Read emergent-reader texts with purpose and understanding.

1st, 2nd, and 3rd grade

- Read with sufficient accuracy and fluency to support comprehension.

- Read on-level text with purpose and understanding.

- Read on-level text orally with accuracy, appropriate rate, and expression on successive readings.

- Use context to confirm or self-correct word recognition and understanding, rereading as necessary.

A student can be seen reading laboriously, trying to sound out every letter while reading. For the word “he,” the student sounds /h/ and /e/, getting confused about what word that might be. It happens with “laugh,” “night,” “here,” “her,” and “she” as well. The student’s inability to recognize high-frequency words automatically by sight and their lack of pattern recognition leads to a frustrating experience in reading. When the teacher asks comprehension questions about the story, the student does not remember much of what they just read. This demonstrates how a lack of fluency impacts reading comprehension in children. This chapter presents research-based strategies for building fluency and comprehension in children.

Comprehension, fluency, vocabulary, phonics, and phonological awareness form the five components of reading. They work together to support proficient reading, whereby children read with purpose and understanding.

Comprehension is understanding. Understanding the elements of a story helps children to comprehend the story. The following video demonstrates the elements of a story.

The role of motivation in reading

Motivation and engagement are also crucial for skilled reading (Kamil et al., 2011; Wigfield & Asher, 1984). You can motivate readers and engage them through the following steps:

- Have goals and a purpose for reading (Guthrie & Hummenick, 2004).

- Engage children in applying their knowledge of reading strategies (Guthrie & Wigfield, 2000).

- Have children self-regulate their reading processes (Clay, 1991).

- Leverage children’s interest in a topic (Wigfield & Asher, 1984).

- Provide them choices about what to read (Guthrie & Wigfield, 2000).

- Engage them in dialogic conversations, peer discussions, and so on.

- Have various authentic classroom reading experiences to cultivate joy: shared reading, read-aloud, guided reading, and independent reading experiences. Invite guardians and role models to read aloud. Connect with authors through a video-conferencing platform.

- Model and explicitly teach the required skills systematically to scaffold and support developing readers.

- Have one-on-one reading conferences with children (Cunningham & Allington, 2016).

- Provide a print-rich environment with various genres of books and materials in digital and print-based formats. Send home books to read to siblings and parents.

The science of reading

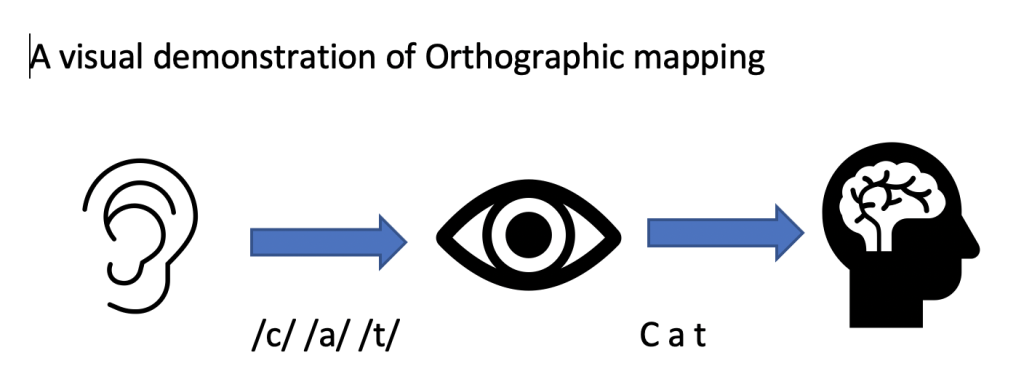

The science of reading is based on interdisciplinary research from linguistics, education, psychology, and neuroscience. The science of reading emphasizes empowering children with problem-solving decoding strategies rather than having them use clues to guess words. Reading involves orthographic mapping, which is a process of connecting sounds (phonemes) in the oral language to letters (graphemes) or letter sequences (patterns) to permanently store words in our long-term memory. For example, /c/a/t/ — C a t

Orthographic mapping

Orthographic mapping applies phoneme-grapheme association, pattern recognition, and automaticity in word recognition to decode words. Practicing sight-word (high-frequency words) recognition, reinforcing the alphabet letters and sounds, and working with word families through word sorts and word work (making words) all scaffold orthographic mapping. Systematic, explicit phonics instruction with continual “review and repeat” cycles helps children develop fluency. Follow the structured literacy guidelines to support learners having reading difficulties.

Our brains can attend to only a few things at a time. If most of the children’s attention is focused on decoding words, it is hard for them to simultaneously apply their background knowledge to make connections while reading (linguistic comprehension). According to the National Reading Panel (2000) study, if a text is read laboriously, it will be difficult for children to remember what has been read and relate the ideas to their background knowledge.

Therefore, children must become fluent in decoding words and making text-to-self, text-to-text, and text-to-world connections, applying their background knowledge, vocabulary, native-language-literacy knowledge, knowledge of the target language’s linguistic structure, and verbal reasoning to develop reading comprehension.

The Simple View of Reading

Gough and Turner (1986) proposed that reading comprehension (RC) is the product of decoding (D) and language comprehension (LC).

Building upon Gough and Turner’s work, Scarborough (2001) conceptualized skilled reading as a braid of fluent word recognition and simultaneous language comprehension.

The strands of word recognition consist of phonological awareness, decoding (knowledge of alphabetic principle, phoneme-grapheme correspondence), and sight word recognition. The word recognition strand is increasingly automatic.

On the other hand, the language comprehension strand is increasingly strategic and consists of background knowledge, vocabulary, language structures, verbal reasoning, and literacy knowledge.

According to the Simple View of Reading, children need both word recognition (decoding) and language comprehension to read proficiently, as shown in the example below.

This video explains the simple view of reading and what it means for meaning-making in students:

Fluent word recognition

Fluent word recognition depends on phonological awareness, decoding skills, and sight-word recognition. Fluent word recognition requires developing automaticity. Phonological awareness is an auditory skill and is developed by manipulating sounds. Students’ decoding skills develop from explicit and systematic phonics instruction. Sight-word recognition occurs when high-frequency words are recognized automatically and effortlessly. Sight words may not lend themselves to being easily decoded and are learned after abundant exposure, for example, “does,” “she,” “he,” “here,” and so on.

Language comprehension

Language comprehension depends on background knowledge, vocabulary, language structure, verbal reasoning, and literacy knowledge. Language comprehension is strategic and requires knowing the background information about the topic, having the vocabulary and syntax, and applying verbal reasoning.

What is fluency?

“Fluency is the ability to read most words in context quickly and accurately with proper expression” (Cunningham & Allington, 2016, p. 46). The expectation is for students to read on-grade-level text with purpose and understanding. Also, fluent reading aims for students to read on-level text accurately with proper expression at a comfortable, appropriate rate upon successive readings.

What is fluent reading?

Fluent reading (Rasinski, 2003) is being able to:

- quickly and automatically identify the words;

- read in prosody (in phrases and not word by word), and

- read expressively as if speaking.

There is a misconception that fluency means being able to read fast. This view is reinforced by standardized fluency assessments of student progress (such as Dibels), where students are timed on how many words they can read within a minute. The focus on speed reading detracts from the importance of making connections, resulting in a lack of reading comprehension. Therefore, it becomes essential to have students practice expressive reading at a comfortable pace with purpose and understanding. Readers’ theater and oral poetry reading leverage authentic, meaningful engagement that taps students’ creativity while developing their reading fluency.

What is comprehension?

Comprehension is synonymous with understanding. It is the ability to derive meaning from the text. Meaning-making requires understanding the pertinent vocabulary and background knowledge of the topic. Comprehending the text also requires knowing the text structure (organization of the text) and text features.

The text features include the table of contents, headings, subheadings, captions, glossary, index, diagrams, maps, labels, charts, graphs, and tables. Informational or nonfiction text has features depending on the discipline or content. For example, a social studies text will have maps, whereas a science text will have diagrams.

Some text features are common across content areas, such as a glossary, index, table of contents, headings and subheadings, tables, charts, and graphs. Comprehending informational text requires close attention to these features, understanding the content-area vocabulary, and background knowledge of the discipline.

A narrative text is often organized in a descriptive or problem-solution structure with a beginning, middle, and end. The narrative text is categorized into personal narrative or fictional narrative.

Personal narratives

Personal narratives can be autobiographies, journals (dialogue journals, diaries, simulated journals), memoirs, biographies, and poetry (bio-poems, where am I from, 6-word memoirs, etc.). Children in PreK-2 can be guided in writing diamantes (diamond-shaped opposite poems), limericks (rhyming poems), and cinquains (five-line poems). Bio-poems can be modified for PreK-2 grades.

Fictional narratives

Fictional narratives or stories have literary elements such as setting, characters, plot (problem, events, solution), and theme or main idea. Fictional narratives come in the following genres: realistic fiction (contemporary), science fiction, historical fiction, fantasy, and traditional literature (myths, fables, and folktales). Understanding fictional narratives necessitate paying particular attention to literary elements. This instruction can be approached through think-aloud and dialogic reading. Retelling stories with their beginning, middle, and ending parts reinforce their structures in children’s minds.

Dialogic reading

Dialogic reading is especially pertinent for oral-language development and comprehension. Dialogic reading is done by conversing about a book with children using the CROWD+HS questions and PEER+PA dialogue. You may explore Iowa Reading Research Center’s interactive-reading guide and the CROWD and PEER bookmarks.

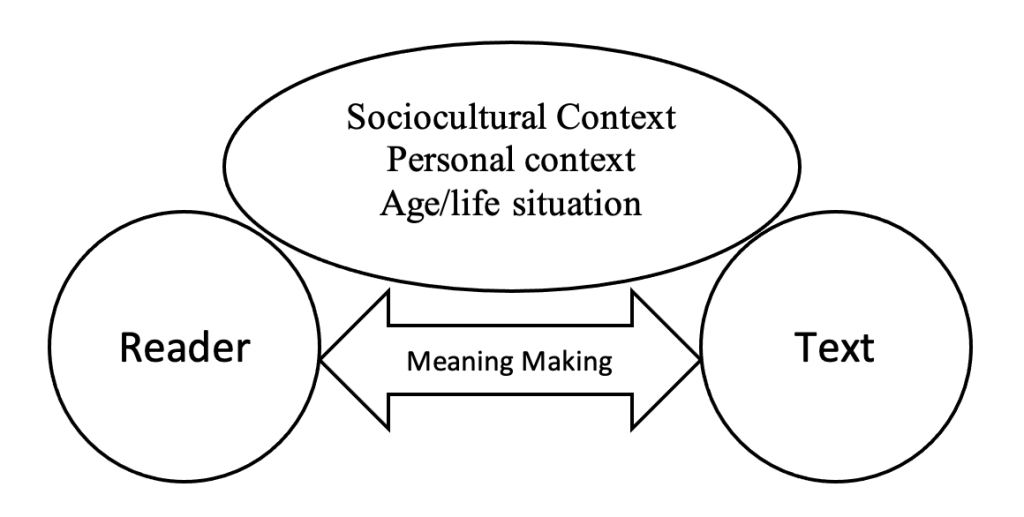

Rosenblatt (1994) believed active reading is a transactional process between the reader and the text. Reading requires active engagement with the text. The task (reader’s purpose) also plays a role in constructing meaning from the text. As a child reads, they make text-to-self, text-to-text, and text-to-world connections. Making connections and associations facilitates comprehension. The child’s language, culture, life experiences, and prior knowledge influence the process.

The socio-cultural context (Vygotsky, 1978) plays a role in meaning-making. Children may read the same book yet derive different meanings from it based on their life experiences. Children’s meaning-making is influenced by their socio-cultural context, life situation, knowledge of the topic and vocabulary, language, culture, and the unique progression of their literacy development.

One implication for the classroom instruction of younger readers is that some of them may come with limited background knowledge due to their life experiences and limited access to books at home. It is, therefore, essential to fill those gaps in knowledge through various means to facilitate their reading comprehension. Having various reading and writing experiences across content areas supports the building of this background knowledge.

The reader may read for either an efferent or an aesthetic reading purpose. Efferent reading is for gaining information. Most nonfiction text is read with an efferent purpose in mind. Narrative text may also be read to gain information to be able to retell.

Aesthetic reading is mainly for the enjoyment of the text. Independent reading time should be for aesthetic purposes, where children are reading to enjoy books. They should not be required to do a book report/related book activity during independent reading time.

Learning environments promote fluency and comprehension

A print-rich learning environment is essential for promoting literacy in children. Young children see print and understand that it communicates meaning. A classroom can be made into a print-rich learning environment by creating a word wall containing high-frequency words.

Other ways to add to a print-rich learning environment are to display relevant anchor charts and student work samples in the classroom. Displaying student work samples allows them to take pride in their work and builds their self-confidence and self-esteem to see adults acknowledge it.

Stock classroom libraries with digital and print-based children’s literature in various genres that represent student identities and provide windows into other worldviews. Wordless picturebooks are excellent tools to ignite imagination and creativity. Every classroom should have some to address the needs of English-language learners (dual-language learners). Wordless picturebooks leverage the background knowledge and home literacies of the students.

Inviting parents to come to class to read multicultural or traditional literature of their choice builds the home-school connection. It creates a welcoming learning environment where children’s cultural and linguistic identities and cultural heritage are celebrated. Sending books home to read to parents and siblings builds community and home literacies.

Celebrating learning through literacy events creates a joyful, affirming, positive environment of collaboration and mentoring through a school-community partnership. The community comes together to share and celebrate their cultural heritage, language, and culture through reading and writing activities.

Print-rich and inclusive learning environments

Creating a word wall

Start by selecting a few high-frequency words based on student needs. Gradually add words to the wall.

High-frequency word recognition and vocabulary words that sound alike but have different meanings (such as “hear” and “here”) can be written on the word wall.

Utilize the word wall in your instruction. You may make a riddle, or a game and bring attention to a word during reading and writing time.

Selecting children’s literature

Select a variety of high-quality print-based and digital texts in various genres based on student interests. Take an interest inventory at the beginning of the year. Have books on various topics, such as pets, farm animals, sports, princesses, etc. Also, have poetry, science fiction, historical fiction, science fiction, fantasy, traditional literature from different cultures, and nonfiction texts in digital and print-based formats. Ensure access to easy, just right, or challenging books to address the needs of all students in your class.

Choose texts that provide mirrors and windows (Sims Bishop, 1990) to create a print-rich environment for the students to interact with. Mirrors reflect the realities of students’ lives, while windows offer an opportunity to consider other perspectives and broaden their horizons by learning about other contexts.

Reading and writing experiences across content areas

Provide a variety of consistent reading and writing experiences throughout the day, such as shared reading, read-aloud, guided reading, independent reading, and writer’s workshops. Incorporate literacy activities across the curriculum in science, social studies, and math so children can see the literacy connections while reading, writing, listening, speaking, viewing, and visually representing.

Fostering inclusivity to build fluency and comprehension

Fostering inclusivity directly correlates with lowering anxiety (the affective filter) in dual-language learners. If learners are anxious, it interferes with fluent reading and comprehension. Providing the option of reading silently or with a peer lowers anxiety, especially for second-language learners.

Providing comprehensible input suited to the developmental and linguistic abilities of dual language learners and using visuals and other multimodal sources promote comprehension in English Language Learners (ELLs). Respecting the silent phase of the second language (Krashen, 1982), acquiring dual-language learners, and providing comprehensible input promote oral-language development in children. Modeling provides examples for dual-language learners to follow.

Provide a safe, nurturing environment with a low affective filter (lower children’s anxiety due to new cultural and linguistic contexts) where mistakes are necessary for learning. Errors are seen as opportunities for growth and learning. Exploration, experimentation, and iterations cultivate critical thinking, creativity, imagination, and innovation.

Creating a sense of belonging and celebrating diverse identities by welcoming everyone to bring their whole selves and diverse perspectives to the learning process will build self-esteem in children and foster inclusivity, upon which fluency and comprehension can be built.

Strategies to promote fluency

Readers’ theater

Reader’s theater is a play with dialogue where the actors orally read their parts written in a script. Readers’ theater is a powerful, authentic way to build fluency in children while engaging them in meaningful activities. It capitalizes on oral reading with expression by allowing the children to play the roles of characters in the story. It first requires comprehending the story and the characters’ traits to be able to role-play them. Using the voice and tone of the characters, the children read with intonation, pauses, and expression as needed. It is a fun, engaging way to build fluency!

Watch this reader’s theater as an example on YouTube: Reader’s Theater: Building Fluency and Expression.

To implement this fluency-building strategy, look for books with lots of dialogue. You may introduce children to the readers’ theater by choosing simple books with numerous dialogues to build their reading confidence. For example, Little Red Hen has several characters with multiple dialogues. Therefore, it makes for a great readers’-theater experience for young children.

Spoken-word poetry

Spoken-word poetry is performed poetry. The performer uses their voice and gestures to convey strong emotions through the verse. Amanda Gorman’s poem The Hill We Climb can be utilized for spoken-word poetry. To implement this activity in your class, generate a list of topics with the students, or provide them with a choice of topics they may feel passionate about. Plan writing workshop times for the students to write, revise, and polish their writing. When they are ready, they may practice reading their poem with a peer. Volunteers may share their spoken-word poems with the whole class.

Echo reading

Echo reading is when the teacher models reading a line expressively, and the students repeat it after the teacher. The teacher reads a line, and the students repeat it, echoing the teacher. Therefore, this reading approach is called “echo reading.” Echo reading develops fluency as the teacher models reading with expression for the students.

It is the most scaffolded approach for guiding the cadence (musicality of the language) of the language and developing reading fluency. Every language has a different rhythm and cadence, with unique intonation and stress patterns. Echo reading is beneficial for English Language Learners to familiarize them with the pronunciation of words and the intonation/stress patterns of the language.

To implement echo reading, the teacher generally reads the text, pointing to each word in the line to reinforce the one-to-one correspondence between the written and spoken words, and has the children repeat. Shared reading experiences such as echo reading also reinforce the concepts of print and sight-word recognition for young learners.

Sometimes, the teacher claps and sways to the rhythm while reading a sentence, and the children repeat each sentence while copying her movements. Having the children repeat just by listening without the print has the benefit of developing phonological awareness and listening skills. Each teacher needs to consider their own contextual needs and make their own judgment calls about how to implement a particular strategy.

Choral reading

Choral reading is when the teacher and student read together in chorus. To do that, the teacher must first model reading and then have the printed text available at each student’s desk.

You can use poems in reading practice sessions to develop fluency. Have the students pair up with one another to practice choral reading together, thereby scaffolding each other’s reading attempts, then bring the whole group together for a class choral reading.

Another technique is to have the students join at repeated refrains in a book. For example, in the book 5 Little Monkeys Jumping on the Bed, the children can read in unison: “No More monkeys jumping on the bed!” Choral reading makes for an enjoyable reading experience.

Repeated reading

Repeated reading builds fluency. Children’s favorite books make the best texts for repeated reading experiences. Each time the child reads it, they may notice something they didn’t see before, enhancing their comprehension. Repeated reading also improves sight-word recognition and oral reading skills. Ensure that your students have access to easy books during independent reading time. They need consistent independent-reading time, as it allows exploring books based on their interests while re-reading their favorite books for enjoyment develops their fluency.

Repeated reading enhances children’s confidence in reading. The children may record reading their favorite book on Flipgrid after a few repeated reading sessions with peers or family. Encourage them to read to their teddy bear (or plush toy), siblings, peers, guardians, and relatives.

Lack of access to books can be addressed by various initiatives such as book deserts through various statewide programs in which you may get involved. The disparity in book access can be addressed by neighborhood little-library initiatives. Bring a book, take home a book, and spread community and home literacies!

Recorded reading

Recorded reading materials can be listened to anytime and anywhere as long as children can access a device. There are several celebrity read-aloud programs available. Storyline online is a platform that offers virtual read-aloud by celebrities. They update their collection of books periodically to attract kids. There are recorded reading videos by characters from children’s TV shows on the Internet.

Read-aloud (reading to students)

Read-aloud provides modeling for fluent, expressive reading while instilling joy and comfort in the reading experience. Children develop listening comprehension while listening to read aloud. Read-aloud has innumerable socio-emotional and cognitive benefits. This NPR article and podcast provide parents with guidance about making reading aloud to their kids a warm, bonding experience while making them better readers.

Reading aloud enhances phonemic awareness, one of the literacy building blocks in young children. Teachers and guardians model expressive reading while reading aloud and facilitate building children’s vocabulary. Additionally, reading aloud provides access to a text that children might not be able to read on their own and helps them process life and difficult issues through dialogic conversations. With the help of adults, children negotiate meaning. Further, reading aloud builds children’s background knowledge. Through think-aloud and pertinent thought-provoking questions, read-aloud scaffold meaning-making. This PBS article provides the beneficial effects of reading aloud.

Reading aloud involves planning and preparation. First, consider how you would like to introduce the book, author, and illustrator: how would you connect the children’s prior knowledge to the topic? At what points would you ask strategic think-aloud questions without interrupting the story? What are some relevant questions focused on predicting, visualizing, monitoring comprehension, summarizing, and/or evaluating? What story elements (characters, setting, plot, and theme) would you discuss and how? How would you make text-to-self, text-to-text, and text-to-world connections? You may choose to discuss certain aspects of the book in depth depending on the cognitive and affective development of the children.

Shared reading (reading with students)

As the name suggests, shared reading involves a reader sharing a text with an audience. A teacher, for example, reads from a “big book.” In PreK-2, the children sit on a rug while the teacher reads and points at words with a pointer. Pointing demonstrates the one-to-one correspondence of written and spoken words. Shared reading also improves students’ sight-word recognition and concepts about print, such as reading moves from left to right and return sweep to the left to continue reading.

Shared reading builds fluency by modeling expressive reading with voice changes for different characters. It cultivates joy from reading by making it a pleasurable experience where children participate by chiming in at certain spots.

It also supports story comprehension by building a schema for the story structure, with beginning, middle, and end, highlighting the story elements of character, setting, plot, and theme through strategic, thought-provoking questions.

Independent reading (reading by students)

Independent reading by students supports fluency. Motivation plays a huge role in creating independent readers. The students can be motivated by bringing in a variety of texts based on their interests and providing them with choices in reading and writing. There is no follow-up activity or book report to be written on books the children read. Children engage in independent reading for fun and enjoyment. Research (Cunningham & Allington, 2016) shows that the significant motivators of students for reading are teachers’ read-aloud and the students having an independent reading time with books of their own choice.

The purpose of independent reading is the enjoyment of the text. Students should get a consistent independent reading time of at least 20 minutes each day. Teachers must consider how to implement independent reading in their classrooms, including logistics such as when students would select their books for the independent-reading time. What procedures are there already in place to make independent-reading time efficient?

Guided reading (reading by students)

Guided reading is reading by the students under the supervision and guidance of the teacher. Texts are provided at the student’s instructional level. (At the correct instructional level, the word accuracy rate is 90-94% – that is, in a passage of 100 words, the reader makes no more than 10 errors, and the comprehension is 60% or better.) The teacher selects developmentally appropriate book sets. The students read while the teacher listens and makes pertinent observational notes to put in each student’s file.

Fountess and Pinell (2012, 2018) note that guided reading supports differentiated instruction and leads to independent reading. Teachers can provide the children with individualized support through guided reading in small groups.

To implement guided reading, teachers form flexible, homogenous groups based on the instructional needs of the students to guide and model the skills that the students need help with. It involves assessing the needs of the children through various literacy assessments. Students practice the particular skill they need under the teacher’s guidance while the rest of the class works at centers or their desks on their literacy skills. It involves building procedures into the daily schedule. Guided reading builds literacy skills, including fluency and comprehension.

Rasinski (2003) and (Rasinski & Padak, 2013) recommend developing fluency through fluency-development lessons with the following instructional routine. This routine can be completed within 15-20 minutes:

- Read aloud a short poem or interesting passage several times. Help the children comprehend difficult words during the discussion.

- Do a choral reading of the poem or passage as a class several times, assigning different parts for the children to take. The children should have copies of the text.

- Do at least three partner readings of the poem or passage, taking turns reading.

- Ask for volunteers to read the poem or passage to the whole class.

- Have the children choose 2-3 words from the poem/passage to add to their personal dictionary.

- The children take home the text. They are encouraged to share their reading with a parent or guardian.

Strategies to promote comprehension

Early print awareness reflects children’s understanding that print conveys meaning as they explore it in their environment with parents and guardians. Toddlers and preschoolers depend on social clues and physical context to read print (Goodman, 1986). Gradually, they learn directionality, letter names, and the correspondence between letters and sounds to make meaning of the written symbols and words.

Adults play a considerable role in promoting understanding of the text by reading aloud and having children interact with the print in their daily lives. Children develop a story schema through read-aloud with a beginning, middle, and end. They also get exposed to different text structures and features through consistent, shared reading experiences. Furthermore, read-aloud develops vocabulary and prior knowledge to enhance linguistic comprehension.

Guardians and teachers can promote reading comprehension by:

- Reading a variety of narrative and expository texts aloud.

- Choosing books that introduce children to unfamiliar topics, complex syntax, and sophisticated words (Paratore et al., 2011).

- Encouraging children to elaborate, clarify, and reason as they discuss stories (dialogic reading).

- Engaging children in various reading experiences, such as independent reading, shared reading, guided reading, and read-aloud.

- Making consistent time for a daily read-aloud or shared reading and independent reading.

- Building children’s vocabulary by exploring word meanings: Have children illustrate the vocabulary (sketch to stretch), write synonyms, antonyms, and a sentence, or draw a graphic organizer like the Frayer model [PDF]. The Frayer model can be modified to have a combination of words and pictures. Children can also explore vocabulary in their surroundings. Understanding vocabulary supports children’s comprehension.

Understanding narrative text elements

Narrative texts have a story structure with a beginning, middle, and end. Narrative texts have the following story elements:

Setting

Setting indicates when and where a story takes place. To develop an understanding of the setting, explore how the illustrations and word choices in the story contribute to the feeling of the place and time.

Characters

There are major and minor characters in a story. Students can analyze and describe the traits or qualities of the characters through their appearance, words, and actions; they can compare the characters using a Venn diagram or examine how the characters evolved from the beginning to end in longer texts such as chapter books.

Plot

The plot involves the problem, sequence of events, and solution of the story. A plot diagram looks like a horizontal line where the story is introduced. Then the problem is introduced, followed by an escalation of conflict, also known as the sequence of events, until the climax of the action. Finally, the graph looks like a downhill line, representing the release of tension as the problem is resolved. There may be person-to-person conflict, person-to-society conflict, person-to-self conflict, or person-to-nature conflict. Story mapping helps in developing an understanding of the plot.

Theme

Theme indicates the main idea. Themes are generally written as sentences. For example, “slow and steady wins the race.” Have your students identify the story’s main idea while guiding them with questions.

Comprehension strategies for narrative texts

Strategies for helping students comprehend texts include reviewing, predicting, activating prior knowledge, setting a purpose, think-aloud, visualizing, inferring, summarizing, and evaluating.

Before reading

Before reading the story, the book is introduced through the 4 Ps: Preview, Prior knowledge, Prediction, and Purpose.

- Preview: Previewing consists of examining the title, author, and illustrator and taking a picture walk through the book. It can be done with chapter books as well as picturebooks.

- Prior knowledge: Students are encouraged to think about the book’s topic through think-aloud or a question.

- Prediction: To promote active reading, the students are asked to predict something related to the book based on their preview.

- Purpose: Set the purpose of their reading the text. Generally, it is to find information based on the reader’s prediction.

While reading

While reading, the students are encouraged to think about the 5 W’s and H’s: What, Where, When, Why, Who, and How? The placing of strategic questions at points throughout the book will help the children to comprehend the story. The Iowa Reading Research Center recommends using the CROWD+HS questions and PEER+PA dialogue to encourage dialogic reading to promote reading comprehension and oral language development.

Throughout the story, active readers make predictions, they think aloud (“I wonder…, I think…, I feel…”), visualize (“I can vividly see the action happening through the use of descriptive language by the author”), self-monitor (“I don’t understand why…”), summarize (“So far in the story…”), and evaluate (“My favorite part is…”). The ability to infer develops over time as children gain experience with reading and learn to make connections using their background knowledge and information from the text to draw conclusions.

After reading

We make text-to-self, text-to-text, and text-to-world connections during and after reading. Students can summarize stories by story mapping to showcase their understanding.

Story mapping

Story mapping is a visual representation of the various elements of a story. Different graphic organizers can be explored online, such as concept maps, story maps, and others. The elements to consider when mapping the story are setting, characters, problem, sequence of events, solution, and theme (main idea).

Compare and contrast

Students may use Venn diagrams to compare and contrast characters from the same book or different books. This allows them to examine the similarities and differences between the characters.

Writing a bilingual story.

Dual-language learners can write with Rebus (a combination of words and pictures) or a bilingual story using two languages.

Retelling using Bob Prost and Kylene Beers’ BHH Framework (2017)

Developing the skill to retell stories after hearing them in read-aloud, shared-reading experiences, or guided-reading times reinforces the students’ grasp of the beginning-middle-end structure of stories. Retelling skills can be improved over time and made more specific. BHH stands for:

- What is in the book?

- What is in your head?

- What did you take to heart? (The personal connections you made with the story.)

Comprehension strategies for informational texts

Informational text is text that is nonfiction. Newspapers, encyclopedias, and nonfiction books are examples of informational text. The comprehension strategies for informational text are similar to those for narrative text in terms of visualizing, summarizing, and evaluating information. The text features of informational text and content-specific vocabulary require close reading, figuring out or looking up vocabulary words, and paying attention to tables, captions, and headings.

Sketch noting and various graphic organizers can be used to help visualize the information. T-charts and double-entry journals are also great ways to organize the information, with significant points on the left and associated connections on the right. Tree diagrams (Cunningham & Allington, 2016) can summarize the text, with the trunk, branches, and twigs representing the main topic, subtopics, and examples/details.

Scavenger hunts and other gamified learning activities with incentives are excellent methods for comprehending informational text.

The Second Life uses a simulation platform to teach content areas, and Wondropolis uses children’s natural curiosity to teach informational text in a multimodal manner. Newsela provides articles on various informational texts, and you may modify the text difficulty by adjusting for the grade level.

Cunningham and Allington (2016) suggest a “Guess Yes or No,” or “confirm or correct” framework where students first predict and then read to check their predictions. False predictions are corrected with the correct information. For this activity, students can be given anywhere from 10-15 informational statements to make predictions about, read, confirm, or correct.

- How would you support a student who struggles with comprehension but can read words quickly and accurately?

- What are some graphic organizers, sketch noting tools, and virtual simulations that support English Language Learners’ comprehension, and how would you use them in your classroom?

- Fluency and comprehension are correlated.

- Create a print-rich, inclusive learning environment.

- Lower the affective filter by creating a sense of belonging.

- Engage the students in authentic, fun learning experiences that reinforce comprehension and fluency, such as readers’ theater and spoken-word poetry.

- Provide various reading experiences, including buddy/partner reading, shared reading, guided reading, read-aloud, and independent reading.

Resources for teacher educators

- The Go-To Literacy Resources for Literacy Teachers

- Teaching Reading Resources

- Early Learning Resources

- Wonderopolis- A Questioning Resource

- Nonfiction Reading Resource

- Library of Congress Resource

- Science Resource for K-12 Educators

- Smithsonian Learning Lab

- Time for Kids

- 2022 Notable Books: 21 Best Poetry and Verse Novels for Kids | School Library Journal

- 2022 Notable Poetry Books and Verse Novels – NCTE

- Notable Children’s Books – 2022 | Association for Library Service to Children (ALSC)

- Effectiveness of Early Literacy Instruction: Summary of 20 Years of Research

- International Literacy Association’s Resource on the Science of Reading

Professional materials

- Slide deck on fluency: OER Fluency Powerpoint

- Slide decks on comprehension:

Potential assignments

- Consider how you would use wordless picturebooks to support comprehension and fluency in children. Explore some wordless picturebooks and decide on one for children to use as a basis for creating something in small groups that they can perform for an audience. Their performance can fall into any one of the following categories: spoken-word poetry, play, readers’ theater, news report, talk show, infomercial, or any other type you approve that relates to your wordless picturebook.

- Explore online resources for fluency and comprehension to create an early literacy instructional resource center for PreK-3rd grade. Choose from the categories listed below:

-

- File-folder literacy game ideas

- Online lesson plans for literacy development

- Blogs and podcasts related to literacy instruction

- Performance-poetry resources

References

Beers, K. & Probst, B. (2017). Disrupting thinking: Why how we read matters. Scholastic.

Clay, M. M. (1991). Becoming literate: The construction of inner control. Heinemann.

Cunningham, P. and Allington, R. (2016). Classrooms that work: They can all read and write. Pearson.

Fountas, I. C., & Pinnell, G. S. (2018). Every child, every classroom, every day: From vision to action in literacy learning. The Reading Teacher, 72(1), 7–19.

Fountess, I. C. and Pinell, G. S. (2012). Guided reading: The romance and the reality. Reading Teacher, 66(4), 268-284.

Gough, P. B., & Tunmer, W. E. (1986). “Decoding, reading, and reading disability.” Remedial and Special Education: RASE, 7(1), 6–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/074193258600700104

Goodman, Y. (1986). Children coming to know literacy. In W. Teale & E. Sulzby (Eds.). Emergent Literacy: Writing and Reading (pp. 1-14). Ablex.

Guthrie, J. T., & Humenick, N. M. (2004). Motivating students to read: Evidence for classroom practices that increase motivation and achievement. In P. McCardle & V. Chhabra (Eds.), The Voice of Evidence in Reading Research (pp. 329-354). Paul Brookes Publishing.

Guthrie, J. T. & Wigfield, A. (2000). Engagement and motivation in reading. In M. I., Kamil, P.B. Mosenthal, P.D. Pearson, & R. Barr (Eds.). Handbook of Reading Research (Vol III, pp. 403-424). Erlbaum.

Krashen, S. (1982). Acquiring a second language. World Englishes, 1(3), 97-101.

National Reading Panel (2000). Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction: Reports of the subgroups (National Institute of Health Pub. No 00-4754). Washington, DC: National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Paratore, J. R., Cassano, C. M., & Schickedanz, J. A. (2011). Supporting early (and later) literacy development at home and at school: The long view. In M.L. Kamil, P.D. Pearson, E. B. Moje & P.P. Afflerbach (Eds.), Handbook of Reading Research (Vol. IV, pp. 107-135). Routledge.

Rasinski, T. V. (2003). The fluent reader. Scholastic.

Rasinski, T. V., & Padak, N. D. (2013). From phonics to fluency (3rd edition). Allyn & Bacon.

Rosenblatt, L.M. (1994). The transactional theory of reading and writing. In R.B. Ruddell, M.R. Ruddell, & H. Singer (Eds.), Theoretical models and processes of reading (4th ed., pp. 1057–1092). Newark, DE: International Reading Association. doi:10.1598/0872075028.48

Sims Bishop, R. (1990). Mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors. Perspectives, 1(3), ix-xi.

Scarborough, H. S. (2001). Connecting early language and literacy to later reading (dis) abilities: Evidence, theory, and practice. Handbook of Early Literacy Research, 1, 97–110.

Vygotsky, L.S. (1978). Mind and society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.