Suprasegmentals

10 Connected Speech

John M. Levis and Kate Challis

Learning Objectives

To familiarize teachers with connected speech:

- normal spoken form vs. citation/dictionary form

- To enhance teachers’ ability to teach connected speech to students

- To introduce teachers to high-frequency phrases in English that are often pronounced using these 6 categories of connected speech

- To provide exercises for the most common connected speech phrases in English

Outline

10.1 What is connected speech?

Most people have noticed that there are often differences between the dictionary pronunciation of a word (its citation form) and the way it is pronounced when combined with other words in spoken language (its normal form). These differences happen because of the effects of connected speech on the expected pronunciations of words (Alameen & Levis, 2015). When people speak English naturally, their words are usually linked together smoothly without breaks between them. Sometimes, this leaves vowel and consonant sounds mostly the same, linking the sounds of one word to the sounds of another. Sometimes, connecting one word to another is done by adding sounds, deleting sounds, or changing sounds to make articulation smoother. These changes are completely normal but may make it challenging for English language learners to recognize words that they know in isolation.

Normal spoken form vs. dictionary form

The normal spoken form of a word refers to how it is commonly pronounced in natural speech. This form often includes elements of connected speech that connect adjacent sounds. Variations in the normal spoken form of a word may signal register variation (e.g., walking vs. walkin’) and regional accent differences (e.g., FRUStrate vs. frusTRATE).

The dictionary form, also known as the “citation form”, is the standardized pronunciation and form of a word as presented in dictionaries. It is a prescriptive, idealized pronunciation that does not account for speech context. This form provides a clear reference for how a word is articulated in isolation, without the influence of surrounding words or the rhythm of normal speech.

Types of Connected Speech Processes

There are many different ways connected speech processes can be categorized. Processes such as linking, insertion, deletion, and reduction occur within words (e.g., fact [fækt] vs. facts [fæks]), but in this chapter, we describe connected speech processes as occurring across word boundaries. We provide some examples of the following types of connected speech: linking, deletion, insertion, modification, reduction, and multiple processes.

Linking is perhaps the most fundamental feature of connected speech. Linking occurs in all languages in different ways. Linking has been part of English for centuries, but there are no prescribed rules for when linking occurs. In an example of linking, the final [k] in The bike is stolen will connect to the vowel in is, so the sentence will be spoken as “The by kiss stolen.” In this example, the sounds stay the same, and final consonants attach to the following consonants so they sound like they are actually beginning consonant sounds. In other cases, the final sounds change or are deleted because of the sounds next to them.

In connected speech, deletions, additions, reductions, and changes of sounds into other sounds, or even combinations of these modifications, are also common. Deletions can occur when vowels or consonants drop to make it easier for speakers to pronounce. For example, if you hurt your knee, the doctor might say as you are recovering, “You can’t favor it too much.” The [t] in can’t is likely to be deleted because [t] in the middle of three consonants [ntf] is almost always deleted in English. And in speaking casually, the second vowel in favor will be deleted, so that favor it can sound like favorite.

Additions in American English usually occur with connected final and initial vowels, such as in go about [gowəbaʊt] and see Alan [sijælən]. In the first phrase, [w] connects the two vowels (because the first vowel is pronounced further back in the mouth, as is [w]), while in the second, [j] connects the vowels because the first vowel is articulated more toward the front of the mouth, as is [j].

Reductions are ubiquitous in connected speech. They occur in English as a result of stress patterns in words and phrases. When vowels are not in stressed syllables, they mostly change to schwa in connected speech. For example, if you say “I went in to work on Thursday and Friday,” the words in, on, and will all be reduced so that they are pronounced in almost the same way. If you pronounce the words in isolation, they will all sound different, but in connected speech, the differences disappear.

Connected speech processes can even change one sound into another, as in Aren’t you going and Would you help me? In the first, the written <t> sounds like the sound expected of the spelling <ch> and in the second, the written <d> sounds like the sound expected of the letter <j> as in joy, or <ge>, as in gem. Finally, processes can occur together, as in “What do you want to do” being pronounced like “Whadja wanna do”.

Connected speech processes and the changes they introduce to pronunciation are the normal way to speak English. They are not improper English, slang, or sloppy speech. In fact, they occur in even the most formal and careful registers of spoken English (Brown & Kondo-Brown, 2006). Lack of connected speech is so abnormal that it can be a way to diagnose neurodegenerative diseases (Boschi et al., 2017)!

Some types of connected speech may vary based on formal or informal situations (Cauldwell, 2013) or across English accent varieties (Brown & Crowther, 2022). This means that the realizations of connected speech processes in American English will not always be the same as those in British English or Australian English. Connected speech processes characterize normal speech in every type of spoken English, and research consistently indicates that learners improve both their listening comprehension and speech production when connected speech is taught (Musfirah, Razali, & Masna, 2019; Euler, 2014; Kul, 2016).

Why does connected speech happen?

Native English speakers tend not to be aware of producing connected speech (Hardcastle et al., 2010), suggesting that CSPs are automatic and deeply ingrained into our ways of speaking. Some researchers have considered connected speech to be primarily a function of the immediate phonemic environment (Baumann, 1996), especially the effects of coarticulation. This means that the position and movement of the mouth, tongue, teeth, throat, jaw, and face affect the production of adjacent sounds. Other researchers have argued that speech rate, the formality of the speech situation, and other social factors also influence connected speech (Lass, 1984; Anderson-Hsieh, Riney, & Koehler, 1994; Alameen, 2007). Casual, spontaneous speech has often been believed to have more linking and reduction than formal, planned speech (Hieke, 1984), but corpus-informed research by Shockey (2008) contradicts this finding for some CSPs, showing that linking frequency was consistent across casual and formal speech, as well as for fast and slow speech rates.

Connected speech in English often results from differences between stressed and unstressed syllables in English. These differences affect which words are more likely to have pronunciation changes in connected speech. Unstressed syllables are shorter and less carefully articulated than stressed ones, so unstressed syllables are far more likely to undergo vowel reduction. Unstressed syllables are also far more likely to be deleted or changed in connected speech. As a result, unstressed syllables are more likely to be compressed between stressed elements, which has two effects: They are pronounced quickly and less clearly, and this pronunciation makes stressed syllables become more noticeable, resulting in a regular, predictable stress-based rhythm for English speech.

Some descriptions of English pronunciation suggest that no matter how many unstressed elements there are in a sentence, they will all be pronounced in the same amount of time. This is not accurate. In the sentences below, the three stressed words (birds, eat, worms) remain the same and will take about the same amount of time to say. The unstressed syllables are always pronounced more quickly than the stressed ones (Munro, 2020). However, unstressed elements also take time to say, and more unstressed elements take more time than fewer.

| Stress 1 | Stress 2 | Stress 3 |

|---|---|---|

| Birds | eat | worms |

| The birds | eat | the worms |

| The birds | will eat | the worms |

| The birds | will have eaten | some of the worms |

10.2 Why does connected speech matter?

Language learners often struggle with understanding and producing connected speech (Bley-Vroman & Kweon, 2002; Brown & Hilferty, 1986; Brown & Kondo-Brown, 2006; Henrichsen, 1984). Thus, connected speech is especially important for intelligibility and listening comprehension because learners often do not recognize known words when they occur in speech (Ash & Grossman, 2015; Kennedy & Trofimovich, 2008). This means that learners often struggle to understand the normal speech of fluent speakers or think that fluent speech is too fast.

Fortunately, explicit instruction focused on bottom-up listening (listening to the phonetic details of speech) and practicing connected speech consistently helps learners recognize and produce intelligible speech (Kissling, 2018). Cauldwell (2013) describes different types of speech in terms of plants. Very careful speech results in “greenhouse listening” (because each word is planted in its own individual pot). Classroom speech, which is careful and connected, is described as “garden listening” because words are connected but remain easy to distinguish from each other. And normal speech, the kind produced by native speakers when they are focused on communicating, is “jungle listening” because words connect to each other in unpredictable ways. As Celce-Murcia et al. (2010) say, “Our goal as teachers of listening is to help our learners understand fast, messy, authentic speech … [which] … is much more varied and unpredictable than what they need to produce in order to be intelligible” ( ).

Connected speech is also important because learners find it interesting and fun. Language learning that is fun has been shown to increase motivation (Stoimcheva-Kolarska, 2020) and long-term retention (Abourdan, 2009; Birsen, 2017). Connected speech feels like real speech to language learners, and it is. More importantly, learning to hear connected speech will make it easier to listen to the speech of others. Knowing how English speakers connect words together will make it possible to understand others in situations where they seem to be speaking fast, where several people are speaking together, and in normal speech situations where it may otherwise be hard to understand.

10.3 Representing Connected Speech

Although connected speech occurs in every register and genre of spoken English (Hardcastle et al., 2010), there is no consistent way to represent it in writing. Sometimes the dictionary spelling of words is modified intentionally in writing to better reflect connected speech pronunciations in normal speech. Some high-frequency phrases may also have commonly accepted spellings attested to exist for a long time. These spellings also make it easier to recognize connected speech. Consider the following examples:

| Spelling | Connected speech | First attested spelling |

|---|---|---|

| could have | coulda | 1606 |

| going to | gonna | 1806 |

| (I) don’t know | dunno | 1842 |

| would have | woulda | 1845 |

| got to | gotta | 1885 |

| want to | wanna | 1896 |

| should have | shoulda | 1902 |

Historically, these variant spellings, which are sometimes referred to as eye dialect (Picone, 2016), appeared almost exclusively in writing in order to represent direct speech (Weber, 1986), but today respelled forms appear widely across all forms of computer-mediated communication, such as social media and texting (Eisenstein, 2015), for example:

| Word/phrase | Respellings |

|---|---|

| probably | prolly, prally, proly, prbly, prly |

| what | wat, wha, wut, waat, whaat |

| who is this | who dis |

| yes | ya, yup, yah, yass, yaaas |

| trying to | tryna |

| fixing to | finna |

Connected speech in ESL/EFL textbooks and training materials sometimes also uses respelling, as in Weinstein (1982), whose book title Whaddaya Say? represents many connected speech processes. Other ESL/EFL materials focused on linking (Alameen & Levis, 2015) may use the French liaison symbol ‿ to show how sounds are linked across word boundaries. In the examples below, the first links by deleting the [h] in he, while the second connects the [r] to the following vowel sound. (In this book, we will use the French liaison symbol to signal linking.)

has he → ha‿se

four eggs → four‿eggs

10.4 Linking: what it is, when it happens, why it matters

Linking is the process of smoothly connecting one word to another word by connecting ending and beginning sounds. Sometimes linking occurs by preserving all the original sounds (C‿V linking), sometimes by deleting sounds (some types of C‿C linking), sometimes by adding sounds (V‿V linking), and sometimes by changing sounds into other sounds. Linking is normal for all types of speech, but it also differs across dialects and varieties of English.

Linking is also closely related to syllable structure, which is language-dependent. This means that linking can be tricky at first for learners, especially if they come from a language background that has a very different syllable structure from English. Japanese, Korean, Chinese, and Vietnamese generally have fewer “legal” syllable structures than English. Even though Russian, Hindi, and Arabic have many consonant clusters (like English), the kinds of clusters differ from English. However, research has shown that as you practice, you will gain a stronger sense of phonological awareness in English, including an intuition for syllable structure (Saiegh-Haddad, 2019).

C‿V linking

In C-V linking, the consonant sound at the end of one word links to the vowel sound starting the next word as in walk on, found out, and laugh off. This kind of linking ensures that words beginning with vowels will actually sound like they begin with a consonant. The regular pattern for English is consonant + vowel, so this is a frequent linking pattern in English speech.

- some of → su‿muv

- run into → ru‿ninto

- show up → sho‿wup

- zoom in → zoo‿min

- fall apart → fa‿lapart

- rise up → ri‿zup

- check in → che‿kin

- give up → gi‿vup

- work out → wur‿kout

- look over → loo‿kover

When a word ends with a consonant cluster (more than one consonant in a row) and the next word begins with a vowel, the final consonant of the cluster is pronounced in the syllable of the next word. This resyllabification helps English preserve the final consonant as the beginning of the next word.

- first aid → fir‿staid

- post office → po‿stoffice

- guest entrance → gue‿stentrance

- best option → be‿stoption

There are many consonant clusters that are “illegal” in English, but they also sometimes occur because of the tendency to link. For example, in calling someone using the phrase come here, speakers will actually delete the first vowel and say [kmɪɹ]. The consonant cluster [km] is not normally allowed in English, but in this case, it can be pronounced because of linking.

Sometimes, resyllabification creates different real words in English. For example:

- it’s kind of nice →it’s kayn‿dof nice

These could reflect the sounds of two sets of words, either “it’s kind of nice” or “it’s kine dove nice.” However, native English speakers are unlikely to notice this second interpretation because of context clues that make the first sentence something that could be said in English and the second something that could not be said. In the example, “kine dove nice” is unlikely to occur for many reasons. One reason is because these words don’t appear together. By contrast, “kind of” is a high-frequency phrase. Another reason is that the word ‘kine’ (an old word for ‘cow’) is archaic and rare.

When resyllabification creates more frequent word phrases, they can be used for wordplay, such as the children’s rhyme about ice cream.

- ice cream → I‿scream

I scream, you scream, we all scream for ice cream!

C‿C linking

C‿C linking also happens across word boundaries. When the consonant sound at the end of the first word is the same as that begins, the next word makes the same sound or a very similar sound, the tongue can stay in the same place in the mouth and lengthen the consonant sound. Examples of this are seen in full length, Ann knew, and miss some.

Other links can occur when the final stop consonant of the first word links to a different stop consonant beginning the second word, as in Bob‿took‿Tom‿toward‿that‿car. These types of links are often more difficult for learners to hear or produce because the first consonant often sounds like it is deleted or is not pronounced at all. In most cases, it is pronounced, but as a glottal stop (the unwritten sound in uh, oh!) In these links, it is extremely common for one of the consonants to be held and then the second consonant to be fully pronounced.

- drop by → draʔ‿by

- get by → geʔ‿by

- sit down → siʔ‿down

- take down → tayʔ‿down

- look forward to → look‿forwarʔ‿to(/ta)

- wait for → wayʔ‿for(/fer)

This is sometimes referred to as glottalization or to the phonetic process where the glottis (the space between the vocal cords) constricts during the production of a sound, often leading to a characteristic creaky voice or complete closure that stops the airflow momentarily. Glottalization reduces the vocal effort required to maintain a regular speech rhythm and occurs within words, between words, and at the end of words. Both -t and -d glottalization are natural sounding in both formal and informal registers of American English (Shockey, 2008).

V‿V linking (Glide Insertion)

When final vowels link to beginning vowels, the link often occurs because of a glide insertion that matches the first vowel in its place of articulation. For front vowels, the link to the second vowel is made with a brief [j], and for back vowels, the link is made with [w].

Link starting from front vowels

- see it → see‿y‿it

- he asked → he‿y‿asked

- they all→they‿y‿all

Link starting from back vowels

- you always → you‿w‿always

- two eggs → two‿w‿eggs

- go out → go‿w‿out

Another way to show these links is through respelling, using either <w> or <y> spellings. This is often more accessible to learners, and even native speakers may spell familiar words this way when they know the word but have never written it. For example, one student in a class once wrote <cwoperashun> for cooperation.

- do it → do<w>it

- I am → I<y>am

- go on → go<w>awn

- he is → he<y>is

- see it → see<y>it

- coffee or tea → coffee<y>or tea

- two apples → two<w>apples

- be able → be<y>able

10.5 Deletion: What it is, when it happens, why it matters

Another type of connected speech change to pronunciation involves deletion (also called elision). Deletion occurs with consonants and vowels. When it occurs with vowels, it means that the number of syllables changes, which can cause meaning to be asked. Jenkins (2000), in her discussion of the Lingua Franca Core for intelligibility, argues that deletions are particularly challenging for L2 learners because they cannot easily reconstruct words when sounds and syllables are missing.

Consonant Deletion

When consonant clusters occur in spoken English, either within or across word boundaries, one or more consonant sounds may not be pronounced. For example, in the compound noun rest stop, the [stst] is simplified to [stst] so the word could be respelled res top and still sound the same. When one consonant “swallows” other consonant sounds, this is called deletion. It is more common for sounds to be deleted at the end of a syllable than at the beginning of a syllable because the clear pronunciation of beginning consonants is especially important to listeners (Shockey, 2008).

Commonly deleted consonants

- grand prize → gran‿prize

- sound proof → soun‿proof

- last call → las‿call

- lost cat → los‿cat

- twelfth night → twelf‿night

- left the → lef‿the

- and for → an‿for

- take care of myself → tay‿kaira‿myself

- neck of the woods → necka‿the‿ woods

Some very frequent phrases result in other deletions.

- kind of → kin‿da→kain‿na (kinna)

- want to → wan‿to→wan‿na (wanna)

- held back →hel‿back

- give me →gim‿me (gimme)

- let me→lem‿me (lemme)

h-dropping

The sound /h/ at the beginning of words is often weakly articulated and prone to deletion, especially when /h/ occurs at the beginning of an unstressed word. This happens most often with function words such as pronouns (he, him, his, her, hers, himself, herself). In fact, the pronoun it, which used to be hit, is a product of historical h-dropping! The use of h-dropping is used in this child’s rhyme “Fuzzy Wuzzy” in which the made-up word “Wuzzy” is pronounced identically to the last line, “was he.”

Fuzzy Wuzzy was a bear

Fuzzy Wuzzy had no hair

Fuzzy Wuzzy wasn’t fuzzy, was he?

h-dropping also occurs in all forms of the auxiliary verb to have (have, has, had). This leads to have, has, and had being pronounced as [əv], [əz] and [əd]. Phrases like should have, would have, and could have can thus be spelled as should’ve, would’ve, and could’ve.

- should have → shou‿duv (should’ve)

- would have → wou‿duv (would’ve)

- could have → cou‿duv (could’ve)

Interestingly, when an <h> is replaced with an apostrophe <‘> in respelling words that are not contractions, this usually implies the presence of a British English accent, in which this feature continues to be strongly associated with urban, working-class British accents.

Harry’s right here! vs. ‘arry’s right ‘ere!

10.6 Modification: What it is, when it happens, why it matters

By now, it should be clear that the citation form of a word tends to change based on nearby sounds of surrounding words, i.e., its phonetic environment. Modification refers to the broad category of sound changes that involve changing expected sounds to better adapt to their phonetic environment. Linking is about connecting words between word boundaries. Insertion/deletion are about modifying words and phrases so that they comply with phonotactic constraints (meaning the “allowable” sound combinations), including adding or removing syllables. Modification in connected speech is about the naturally occurring sound changes that lead to smoother, more fluid speech, but they do not typically change the number of sounds or the basic structure of the words themselves. Native speakers tend not to be consciously aware of modifications in connected speech.

Flapping

When /t/ or /d/ occurs between vowels, this often results in a “flap” /ɾ/ in North Aerican English, which is a sound produced by briefly tapping your tongue on the small ridge located just behind your upper front teeth on the roof of your mouth.

The flap sound is a lot like /d/ except it is much faster and less distinct, and it seems to occur immediately between syllable boundaries, similar to glides.Flapping is extremely common in all registers of American English, both within words and across word boundaries. If the /t/ or /d/ is preceded by a sonorous consonant sound, meaning with a relatively open airflow through the vocal tract such as /m, n, ŋ, l, r, w, j/, then a flap can still occur.

- a lot of → uh‿lo‿ɾuv

- but I → bu‿ɾeye

- that it → tha‿ɾit

- you hurt it → you‿hur‿ɾit

- right away → ri‿ɾa‿way

- what if → wuh‿ɾif

- got to go → go‿ɾa‿go

- get over it → ge‿ɾoh‿vu‿rit

Some people use glottalization /ʔ/ in places where other people use flaps /ɾ/, that is, flaps (Eddington & Taylor, 2009).

Assimilation

Assimilation refers to one sound taking on some or most of the same characteristics of a neighboring sound. The characteristics that are most often assimilated are the place of articulation, manner of articulation, and voicing. When assimilation occurs across word boundaries, the transitions between sounds become smoother. Assimilation occurs in all languages and makes rapid, fluid speech possible. Note that some of these assimilations result in the loss of eth, the voiced interdental fricative in words like they, the, and then. Cauldwell (2013) calls this process “eth death”.

- and then → an‿nen

- and they → an‿ney

- on the → aw‿ne

- you have → yoov

- in the → in‿ne

- I would → I‿ud (I’d)

- find them → fi‿nem

Blending (Palatalization)

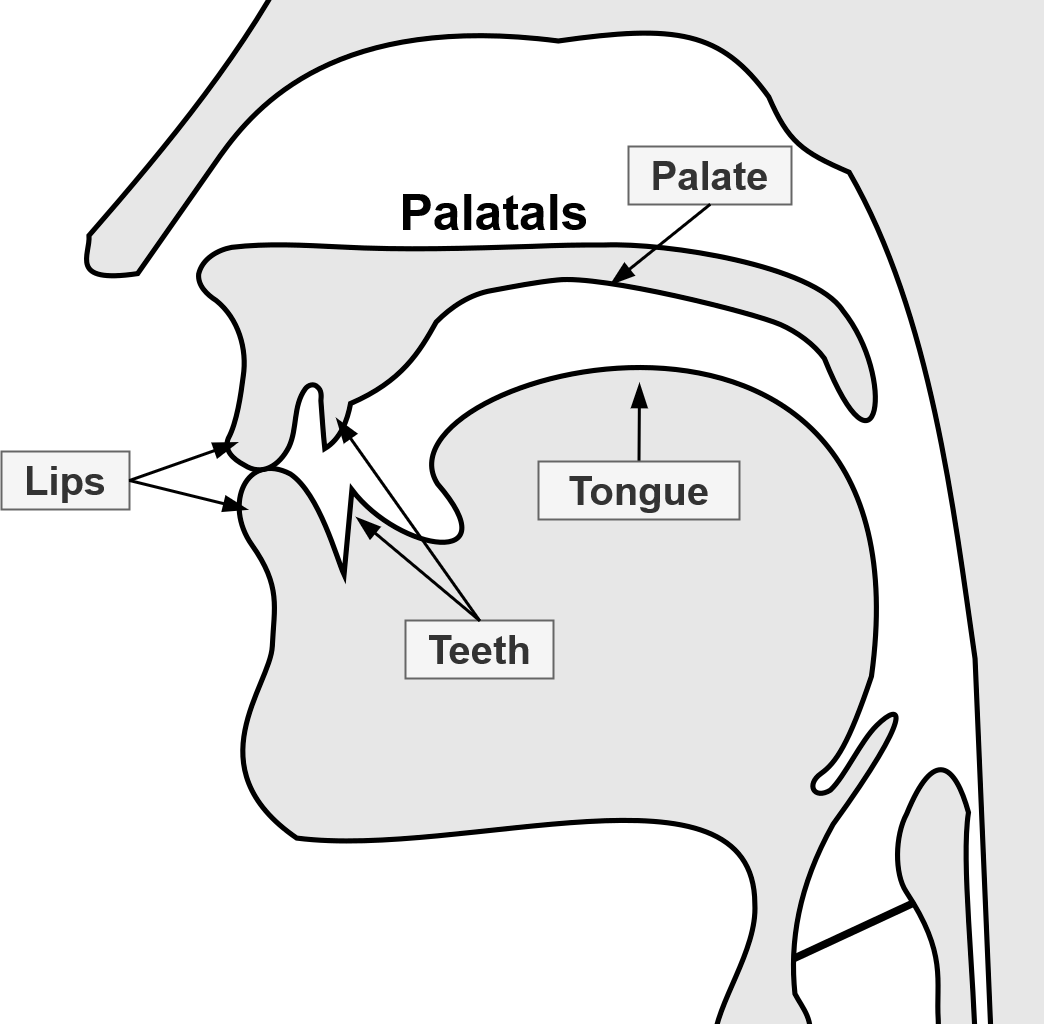

A very common sound change in English connected speech is blending, sometimes called palatalization. Blending happens when the tongue touches the palate while a consonant is being pronounced. Look at the picture and locate the palate.

In some languages, such as Russian and Czech, palatal consonants are phonemic, meaning they are considered to be stand-alone sounds. However, in English, palatalization can also be allophonic, meaning it is a “subcategory” of other sounds or groups of sounds. Palatalization in English usually occurs across multiple consonant sounds, especially those which cross word boundaries. Although the degree to which these consonants are palatalized varies across speaker and context, it occurs so frequently and across so many different kinds of speech that it is important to be able to recognize this pattern.

- /s/ + /j/ → /ʃ/

- /z/ + /j/→/ʒ/

- /d/ + /j/ →/dʒ/

- /t/ + /j/ →/tʃ/

- pass your plate → pa‿shur‿plate

- where’s your → wear‿zhur

- What are you thinking? → wha‿tcha‿thin‿king

- What do you think? → wha‿djoo‿thinkʔ

- What did you think? → wha‿dja‿thinkʔ

10.7 Reduction (Weak Forms)

Reduction is everywhere in English because of the effects of stress on pronunciation. Unstressed syllables are also called reduced syllables, which include sounds that are less distinct and clearly articulated. Their vowels are more prone to being pronounced as the same world, schwa, and their consonants are more prone to change (deletion or blending).

Discourse-level reduction occurs because of words that are known to have two types of pronunciation: weak forms (or normal forms) and strong forms (when a weak form is especially emphasized). Weak forms are high-frequency one-syllable words that are almost never stressed in speech and connect to stressed words. Some weak forms are shown below.

| Spelled Word | Strong form | Weak form |

|---|---|---|

| and | [ænd] | [ən], [n̩] |

| in | [ɪn] | [ən], [n̩] |

| on | [ɔn] | [ən], [n̩] |

| of | [əv] | [ə] |

| an | [æn] | [ən] |

| can | [kæn] | [kn̩] |

| to | [tu] | [tə] |

| will | [wɪl] | [əl], [l̩] |

When combined with other words, weak forms are hard to hear, especially in high-frequency phrases.

- to you → ta‿ ya, tya

- of the → uh‿th

- you know → y‿no

- I don’t know → I‿dunno

- see you → see‿ya

- you never know → ya‿never‿know

10.8 Multiple Processes

The categories of connected speech can sometimes be a bit blurry. The reality is that multiple phonetic processes often interact simultaneously to produce natural-sounding speech. For this reason, Cauldwell (2013) describes connected speech as “jungle listening”. Even if two native English speakers were chatting together in a quiet room, they would produce so many overlapping sounds that it would sometimes be difficult to isolate and identify individual sounds, similar to how it would be difficult to discern where one plant begins and another ends within a jungle.

The point is that the categories we have described in this chapter are simplifications that help organize a complex topic into more manageable pieces for the learner. In tspeech, these processes usually overlap. Native speakers produce multiple connected speech processes simultaneously, usually without ever being aware that their words sound quite different from the dictionary form. The interaction of these processes not only helps maintain the rhythm and flow of speech but also supports the speaker’s linguistic identity and social signaling within specific dialects or language communities.

10.9 Technology Corner

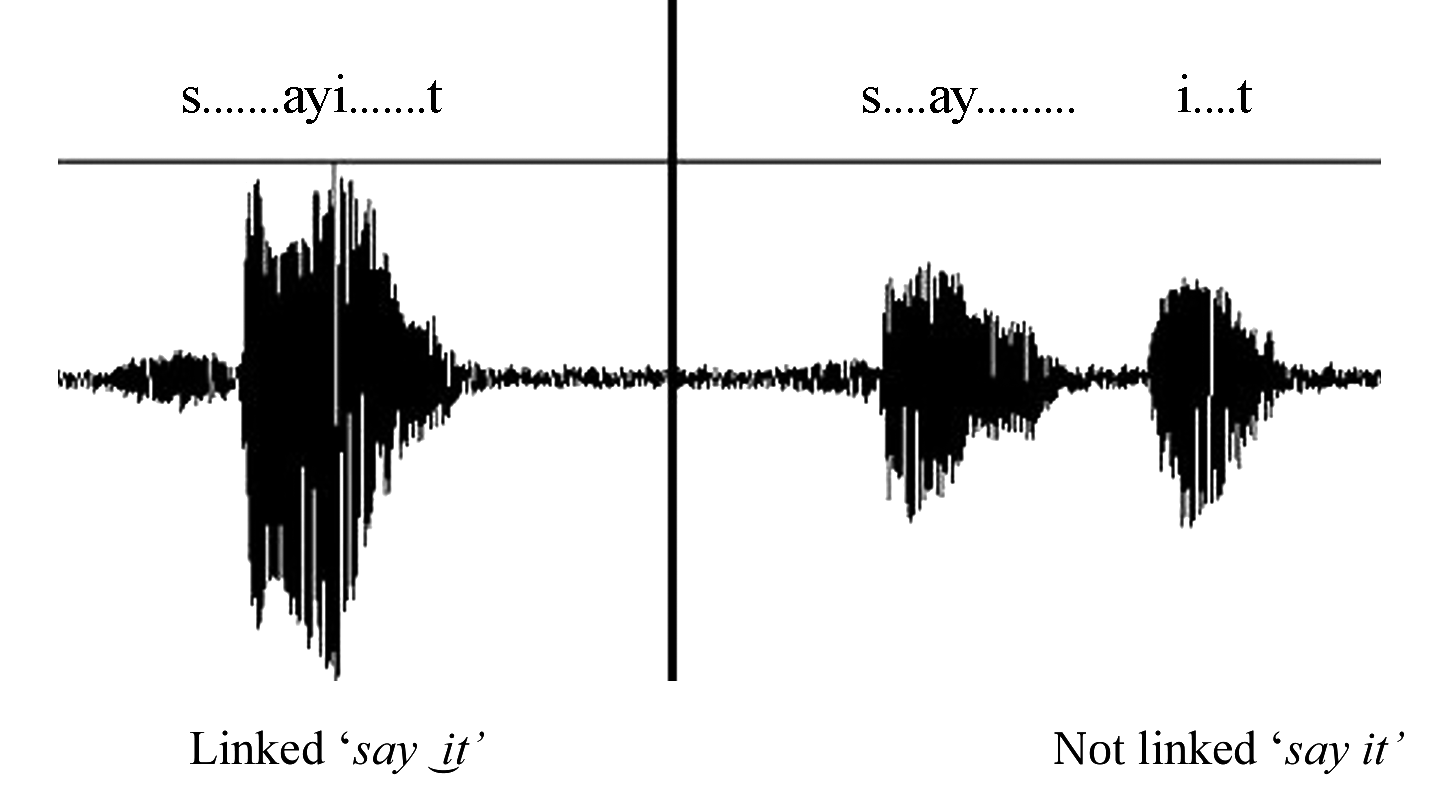

Technology can demonstrate the difference between linked and unlinked words by looking at the waveforms of recordings. Alameen (2014, p. 146) shows this difference using the words say it. The linked version shows no space between the words, but the unlinked form has a clear space between the words.

10.10 ProFunciation

Although connected speech is especially difficult for language learners, it can even be challenging for native speakers in some situations, leading to mishearings that can be comical. For example, one of the authors, in speaking to a staff member about a newly painted room, said “It’s a very yellow room.” The staff member replied, “It’ll look better with marijuana” (or so the author heard). This made no sense in so many ways, and the author finally figured out that the staff member had said, “It’ll look better with a mural on it.” “mural on it” and “marijuana” have the same stress patterns, and the unstressed syllables were not clear enough to hear what was intended.

Some of the most well-known types of mishearings have been named Mondegreens, a term coined by Sylvia Wright (1954), who reported interpreting the phrase “laid him on the green” as “Lady Mondegreen”. These mishearings often occur in songs when the mixture of music and unfamiliar words and grammar force listeners to come up with words that seem to match the sounds they are hearing. In the Christmas carol, The 12 Days of Christmas, most people hear “four calling birds” even though the original words include the archaic word “colly” instead. In another example, the song “In a Gadda da Vida” was originally supposed to be “In the Garden of Eden” but the band members had a difficult time singing the original words.

The following memes show how spelling variations to highlight connected speech features are used to mark humor. In the first line, just and remember both have deletions. Notice how the word-final/t/ and word-initial <re>, which are reduced in normal spoken form, are purposely misspelled. While the second line is full of respellings that do not reflect actual variations in pronunciation, part of the humor in this meme is the use of pronunciation respellings (Picone, 2016), perhaps suggesting that if the kitten could speak, it would speak informally, or like an young child.

Creative spellings of connected speech are sometimes used in song lyrics. In fact, the practice of spelling song lyrics to better reflect how they sound is common in all types of popular music, as in the examples below.

it’s wonderful → ‘s wonderful

“‘s wonderful! ‘s marvelous! That you should care for me! ‘s awful nice! ‘s paradise! ‘s what I love to see!” (Gershwin, 1928)

“She wanna roll, we ’bout to go, what’s hatnin'” (Bieber, 2013)

- she wants to roll → she wanna roll

- we (are) about to go → we ’bout to go

- what’s happening → what’s hatnin’

10.11 Activities

Description and Analysis

Exercise 10-1. Common Connected Speech Changes

Background: In normal speech, words are fluently connected to each other. This makes speech sound too fast and can make it hard to understand what is being said because sounds are not connected to the right word or change from what is expected.

Directions: Write all italicized phrases with underlining so learners can see them. Play recordings of each phrase and ask learners what is happening to the underlined letters. For example, for the first row, ask “How any consonant sounds are pronounced in the underlined section?” When someone says “one” ask them why (because the two sounds are identical, so only one is said).

(Two of the same sounds become one sound)

take care

hip pocket

in November

(Border sounds stay the same but connect to different words)

kicks at the ball

called Ann

slid on the ice

(Two sounds change into a different sound)

did you

hit your head

pass your papers in

(A consonant sound is not pronounced)

brand new car

fast driver

the tenth circle

(Two vowels link together)

A snow angel

play it again

true answers

Listening Discrimination

Exercise 10-2. Lining or no Linking?

Directions: Listen to each phrase. Are the words linked together? Answer Yes or No.

| Phrase | Linked? Select One |

|---|---|

| sick students | YES or NO |

| did you | YES or NO |

| hit your head | YES or NO |

| full length | YES or NO |

| close enough | YES or NO |

| fast car | YES or NO |

| loves ice cream | YES or NO |

| miss your pet | YES or NO |

| was that hard? | YES or NO |

| sings a song | YES or NO |

| catch a cold | YES or NO |

| planned trip | YES or NO |

Listening

Answers

Exercise 10-3. Identifying linking

Directions: Identify which underlined letters are linked correctly. Answer “1” or “2”.

Examples:

The weak kick (1) missed Tim (2).

Did you say kiss you (1) or miss you?

Listen and answer

I built it (1) not billed it. (2)

Did you do it (1) or did you? (2)

I never run. (1) I’d rather ride, (2)

You laugh at (1) me. Don’t laugh again, (2)

I’m eating right now. (1) Can Tom answer? (2)

I want you (1) to count your money (2)

Is it a brand name (1)or a knock-off? (2)

I fell on (1) John’s sidewalk. (2)

Answers

Exercise 10-4. Gapped dictation,

Directions: Listen to the sentences and fill in the blanks. Blanks may have more than one word that are linked together.

- _________ married ________ ________ seven years.

- Things ________ never ________ better.

- ________ never had any problems ________.

- ________ got ________ deal ________ time.

- _______ got _______ start early ______ morning ______ do _______.

- That’s ________ nice restaurant. ________ ________ expensive.

- It’s gotten ________ point ________ can’t even tell.

- This ________ way ________ got ________ be.

- Someone ________ stay ________ keep ________ eye ________kids.

- ________ better go ________answer ________ phone

- ________ already mentioned that ________ while ago

- ________ better bring ________ umbrella.

Controlled Production

Exercise 10-5. Types of Linking

Directions: Read each phrase and link the words together smoothly.

English keeps its distinctive rhythm is by linking or joining words together within each phrase group. 1bis linking happens in almost every possible way. Consonants link to identical or similar consonants, to vowels, and to consonants

Linking Type – Final consonant joins to following /j/ sound (as in you, your)

Didn’t you try?

Did you kiss your cat?

Would you come over?

I miss you a lot.

Close your door.

Place your bets.

Raise your hand.

Linking Type – Final consonant joins to next vowel

Take it slowly

Cats and Dogs

sleep in late,

I’m always on time

walked a mile

swims every day

Linking type – Two different consonants join together in different ways

Take something,

I’m listening.

A cat carrier,

a famous doctor

A white buffalo,

the class clown,

Just sit over there

Linking Type – Two of the same consonants become one sound.

take care

Miss Smith

hip pocket,

I’m making it.

a mad dog

laugh freely

Exercise 10-6. Vowel linking.

Directions: Link the final vowel to the beginning vowel using either a <y> or <w> sound.

Linking using a <y>

They asked for it.

He uses it.

Did you see Ellen?

I owned it.

I ate it.

Ray etched it.

Kay eats there.

Linking using a <w>

Joe ought to go.

A yellow apple.

How are you?

How often do you go?

You owned it?

Joe ate it?

He has blue eyes.

Exercise 10-7. Vowel linking with “the”

Directions: Link the word “the” to the following vowel using a <y> link. To link, pronounce “the” as [ði]. When there is no following vowel, there is no link. Pronounce “the” as [ðə].

Linking using a <y>

the other ones

on the other hand

the only explanation

the ending

the appropriate answer

the usual suspects

No Linking

the next ones

on the one hand

the perfect explanation

the beginning

the mistaken answer

the birdcage

Exercise 10-8. Linking in Rhyming Sayings.

Directions: Match the sayings to their explanations. Then practice saying each one by using linking.

Sayings

- Birds of a feather flock together.

- He’s really cruisin’ for a bruisin’.

- Different strokes for different folks.

- A friend in need is a friend indeed.

- Haste makes waste.

- Might makes right.

- No pain, no gain.

- Whatever floats your boat.

- You snooze, you lose

Meanings

- Doing something quickly makes more work

- Power determines what people accept

- Sleeping causes you to lose good things

- Similar people always find each other

- That person’s looking for trouble.

- Getting something good requires working really hard

- Different people like different things

- People who help you in bad times are the best friends

- It’s not for me, but it sounds like it’s good for you

Extension Activity: Discuss whether you believe these sayings are accurate.

Exercise 10-9. Riddles 1 (from R. Wong, 1987).

Directions: In groups of 5, read a riddle to with correct linking. Then discuss the answer.

Riddle 1

What’s round like an apple, Shaped like a pear,

With a slit in the middle, All covered with hair? (a peach)

Riddle 2

Round as an apple, flat as a hip,

Got two eyes and can’t see a bit? (a button)

Riddle 3

Walk on the living, they don’t even mumble,

Walk on the dead, they grumble and grumble. (leaves)

Riddle 4

Comes in at every window, And every door crack,

Runs around and round the house, But never leaves a track. (the wind)

Riddle 5

Brothers and sisters have I none,

But that m,an’s father was my father’s son. (a man looking at his own picture)

Exercise 10-10. Riddles 2.

Directions: Read with correct linking the riddles from the contest between Bilbo and Gollum in the Hobbit: Watch the clip

Thirty white horses on a red hill,

First they champ,

Then they stamp,

Then they stand still. (Teeth)

Voiceless it cries,

Wingless flutters,

Toothless bites,

Mouthless mutters. (Wind)

A box without hinges, key, or lid,

Yet golden treasure inside is hid. (An egg)

All things they devour us:

Birds, beasts, trees, flowers;

Gnaws iron, bites steel;

Grinds hard stones to meal;

Slays king, ruins town,

And beats high mountain down. (Time)

Exercise 10-11. Puns.

Directions: Listen to, then read the puns (humorous statements that are the result of two statements that sound the same or are very close to the same so that both meanings come to a listener’s mind). Then discuss whether you think the jokes are funny. (Not all people find puns very funny, as this article from the Atlantic shows: “Why do people hate puns?”).

- Becoming a vegetarian is one big missed steak. (mistake)

- What do you call the wife of a hippie? A Mrs. Hippie (Mississippi)

- How does Moses make coffee? Hebrews it. (he brews it)

- What did the buffalo say to his child? Bison. (Bye, son)

- Ladies, if your husband can’t appreciate fruit jokes, you need to let that mango. (man go)

- Do you know any good rope jokes? I’m a frayed knot. (I’m afraid not).

- Why was six afraid of seven? Because seven ate nine. (seven eight nine)

- Why are bananas so good? Because they have appeal. (a peel)

- Another example of a pun “an ant elope” vs. “an antelope” (from Alameen, 2014, p. 2)

Exercise 10-12. Connected speech. (Adapted from R. Wong, 1987)

Directions: Read the dialogue between two men who are fishing. Their lines are respelled to reflect how they sound. (The actual spelling is provided after the respelling. (Based on a comic from the 1980s)

Respelling (Actual words)

- Fisherman A: Hiya Mac. (Hi (you), Mac.)

- Fisherman B: Lobuddy. (Hello, Buddy.)

- Fisherman A: Binear long? (Have you) been here long?)

- Fisherman B: Cuplours. (Couple of hours.)

- Fisherman A: Ketchineny? (Catching any?)

- Fisherman B: Goddafew. (Got a few.)

- Fisherman A: Kindarthey? ((What) kind are they?)

- Fisherman B: Bassencarp. (Bass and carp.)

- Fisherman A: Enysizetoum? (Any size to them?)

- Fisherman B: Cuplapouns. ((A) couple of pounds.)

- Fisherman A: Watchayoozin? (What are you using?)

- Fisherman B: Bunchawurms. ((A) bunch of worms.)

- Fisherman A: Goddago. (Got to go.)

- Fisherman B: Tubad. OK. Takideezy. (Too bad. Take it easy.)

- Fisherman A: Seeyarown. Gluk. (See you around. Good luck.)

10.12 References

Aboudan, R. (2009). Laugh and learn: Humor and learning a second language. International Journal of Arts and Sciences, 3(3), 90-99.

Alameen, G. (2007). The use of linking by native and non–native speakers of American English. Iowa State University. https://doi.org/10.31274/rtd-180813-16165

Alameen, G. (2014). The effectiveness of linking instruction on NNS speech perception and production. Doctoral dissertation, Iowa State University.

Alameen, G., & Levis, J. M. (2015). Connected speech. In M. Reed & J. Levis (Eds.), The handbook of English pronunciation (pp. 157-174). Wiley Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118346952.ch9

Anderson-Hsieh, J., Riney, T., & Koehler, K. (1994). Connected speech modifications in the English of Japanese ESL learners. Issues and Developments in English and Applied Linguistics, 7, 31-52.

Ash, S., & Grossman, M. (2015). Why study connected speech production. In R. Willems (ed.), Cognitive neuroscience of natural language use (pp. 29-58). Cambridge Univesity Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9781107323667.003

Baumann, M. (1996). The production of syllables in connected speech. Unpublished dissertation, Radboud University.

Bieber, J. (2013). What’s Hatnin’.

Birsen, P. (2017). Effect of gamified game-based learning on L2 vocabulary retention by young learners. (Master’s thesis, Eğitim Bilimleri Enstitüsü).

Bley-Vroman, R., & Kweon, S. O. (2002). Acquisition of the constraints on wanna contraction by advanced second language learners: Universal Grammar and imperfect knowledge. Second Language Research, 27(2), 207-228. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267658310375756

Boschi, V., Catricala, E., Consonni, M., Chesi, C., Moro, A., & Cappa, S. F. (2017). Connected speech in neurodegenerative language disorders: a review. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 208495. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00269

Brown, J. D., & Crowther, D. (2022). Shaping learners’ pronunciation: Teaching the connected speech of North American English. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003144779

Brown, J. D., & Hilferty, A. (1986). The effectiveness of teaching reduced forms of listening comprehension. RELC Journal, 17(2), 59-70. https://doi.org/10.1177/003368828601700204

Brown, J. D., & Kondo-Brown, K. (Eds.). (2006). Perspectives on teaching connected speech to second language speakers (Vol. 1). National Foreign Language Resource Center.

Cauldwell, R. (2014). Listening and pronunciation need separate models of speech. In J. Levis & S. McCrocklin (Eds). Proceedings of the 5th Pronunciation in Second Language Learning and Teaching Conference (pp. 40-44). Ames, IA: Iowa State University.

Celce-Murcia, M., Brinton, D. M., & Goodwin, J. M. (2010). Teaching pronunciation: A course book and reference guide. Cambridge University Press.

Eddington, D., & Taylor, M. (2009). T-glottalization in American English. American Speech, 84(3), 298-314. https://doi.org/10.1215/00031283-2009-023

Eisenstein, J. (2015). Systematic patterning in phonologically‐motivated orthographic variation. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 19(2), 161-188. https://doi.org/10.1111/josl.12119

Euler, S. S. (2014). Assessing instructional effects of proficiency-level EFL pronunciation teaching under a connected speech-based approach. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 4(4), 665–692. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2014.4.4.5

Gershwin, G. (1928). ‘S Wonderful,

Hardcastle, W. J., Laver, J., & Gibbon, F. E. (2010). The handbook of phonetic sciences (2nd ed). Wiley-Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444317251

Henrichsen, L. E. (1984). Sandhi‐variation: A filter of input for learners of ESL. Language Learning, 34(3), 103-123. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-1770.1984.tb00343.x

Hieke, A. E. (1984). Linking as a marker of fluent speech. Language and Speech, 27(4), 343-354. https://doi.org/10.1177/002383098402700405

Jenkins, J. (2000). The phonology of English as an international language. Oxford University Press.

Kennedy, S., & Trofimovich, P. (2008). Intelligibility, comprehensibility, and accentedness of L2 speech: The role of listener experience and semantic context. The Canadian Modern Language Review, 64(3), 459-489. https://doi.org/10.3138/cmlr.64.3.459

Kissling, E. M. (2018). Pronunciation instruction can improve L2 learners’ bottom‐up processing for listening. The Modern Language Journal, 102(4), 653-675. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12512

Kul, M. (2016). Effects of two teaching methods of connected speech in a Polish EFL classroom. Research in Language, 14(4), 389–407. https://doi.org/10.1515/rela-2016-0024

Lass, R. (1984). Phonology: An introduction to basic concepts. Cambridge University Press.

Munro, M. J. (2020). Applying phonetics: Speech science in everyday life. John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781394259786

Musfirah, S., Razali, K., & Masna, Y. (2019). Improving students’ listening comprehension by teaching connected speech. Englisia, 6(2), 64–74. https://doi.org/10.22373/ej.v6i2.4565

Picone, M. D. (2016). Eye dialect and pronunciation respelling in the USA. In V. Cook & D. Ryan (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of the English writing system (pp. 351-366). Routledge.

Saiegh-Haddad, E. (2019). What is phonological awareness in L2?. Journal of Neurolinguistics, 50, 17-27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneuroling.2017.11.001

Shockey, L. (2008). Sound patterns of spoken English. John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470758397

Slade. (1971). Coz I Luv You.

Stoimcheva-Kolarska, D. L. (2020). The Impact of a relaxed and fun learning environment on the second language learning. Online Submission, 2(1), 9-17.

Weber, R. M. (1986). Variations in spelling and the special case of colloquial contractions. Visible Language, 20(4), 413-426.

Weinstein, N. (1982). Whaddaya Say? Prentice Hall Regents.

Wong, R. (1987). Teaching pronunciation: Focus on English rhythm and intonation. Language in Education: Theory and Practice, No. 68. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED283386.pdf