Introduction

1 Basics of Teaching Pronunciation

John M. Levis

- To describe what pronunciation features should be taught

- To explain why pronunciation should be taught

- To explore how pronunciation should be taught

- To explain how sounds are represented for pronunciation teaching

1.1 Introduction

Pronunciation has long been part of teaching in ESL/EFL/ELF contexts, and it is possible to find a wide variety of teaching materials published throughout the 1900s and 2000s. These materials are mostly based on the goal of the adult language learner developing a native-like accent. We now know that developing a native-like accent is highly unlikely because of the influence of age (Scovel, 2000), changes in perception (Flege, 1995), and the influence of a speaker’s identity (Zuengler, 1989). Fortunately, multiple studies have made it clear that foreign-accented speech does not stop a speaker from being understood (e.g., Munro & Derwing, 1995). This means that pronunciation is increasingly visible in English language teaching today for three reasons: a focus on intelligibility rather than native-like accents, evidence that teaching pronunciation works, and the desire for teachers to receive training on pronunciation.

Even though native-like pronunciation is unlikely for most adult learners, pronunciation remains the number one reason L2 speakers of English are not intelligible when speaking English. Jennifer Jenkins (2000), in her ground-breaking study of English as a Lingua Franca intelligibility, found that mispronunciations of consonants and vowels were the most likely causes of intelligibility when L2 speakers spoke with other L2 speakers. (Grammar and vocabulary choice were less likely to cause misunderstanding.) Beth Zielinski (2008), in her study of reduced intelligibility of Chinese, Vietnamese, and Korean speakers, found that mispronunciations in stressed syllables were particularly likely to cause trouble for L1 English listeners. Stress errors, which can also affect the clarity of English vowel pronunciation, seem particularly able to cause a loss of intelligibility (Benrabah, 1997; Field, 2005).

The second reason pronunciation is important is that we now have strong evidence that teaching pronunciation improves student performance. Lee, Jang and Plonsky (2015), in a meta-analysis of previous studies of pronunciation teaching, found that teaching pronunciation almost always resulted in student improvement. This finding is especially important because we also know that just living in an environment where English is spoken typically results in improved pronunciation, but that improvement plateaus after 6-12 months (Thomson, Derwing, &, Munro, 2024). As a result, explicit teaching of pronunciation is essential for improvement in the long run. Derwing et al. (2014), in a study of teaching pronunciation in a workplace (factory) environment, found that intelligibility improved for the adult workers in the study even though they had been in Canada for an average of 19 years. Without explicitly instruction, there would not have been improvement, but with instruction, it was possible for the learners to improve their ability to communicate.

A third reason for the growing visibility of pronunciation is that many teachers want help in learning how pronunciation can be taught. Workshops at conferences or books of activities are very helpful, but growth in pronunciation teaching expertise also requires knowing about appropriate goals for teaching, targets for pronunciation learning, and the ways that multiple activities can be put together to promote learning. In earlier decades, ESL/EFL training programs almost always included pronunciation as a key topic for training teachers, but the rise of the communicative approach to teaching also assumed that pronunciation would improve on its own if we just focused on communication (Levis & Sonsaat, 2017). It eventually became clear that this was not true, but by then, many teacher training programs no longer included pronunciation training, leaving many teachers to gain knowledge of pronunciation in a haphazard way. This book is meant to systematically help teachers who want to learn about the what, why, and how of pronunciation teaching and how it can help them ensure their learners’ communicative success.

1.2 Elements of Pronunciation: The What of Pronunciation Teaching

English pronunciation is one of the most completely described areas in language teaching, and it has a long history of being accessible to teachers of many levels of expertise. Pronunciation involves the articulation of speech sounds, rhythm, and melody to communicate meaning. As such, pronunciation is a basic building block of speaking and listening skills. To speak, we have to pronounce, and to understand others, we have to understand and interpret their pronunciation. In learning a new language, especially as an adult, pronunciation inevitably includes small and large deviations from the ways that native speakers pronounce. The exact nature of these deviations is often influenced by the language(s) that the learner already knows. This is why we can notice that someone has a Spanish accent, a Japanese accent, an Indian accent, or many other distinctive accents that we may be familiar with. Deviations may also come because of the developmental processes of second language acquisition. People who already know one or more languages have become very, very good at hearing the important sound distinctions of their languages, but because different languages have different systems of phonemes (important sounds), learners may not be very good at hearing distinctions that are important in a new language. For example, French and English both have the bilabial stop sounds /p/ and /b/, but the ways that the /p/ and /b/ are actually pronounced is different in English than it is in French. As a result, the English pronunciation of /b/ may sound like /p/ to a French speaker, and a French /p/ will sound like a /b/ to an English speaker. So French and English speakers both have different parameters for what sounds like a /p/ and a /b/. Not only that, speakers of English who are learning French and vice versa have trouble paying attention to these new parameters because they have never needed to do so before.

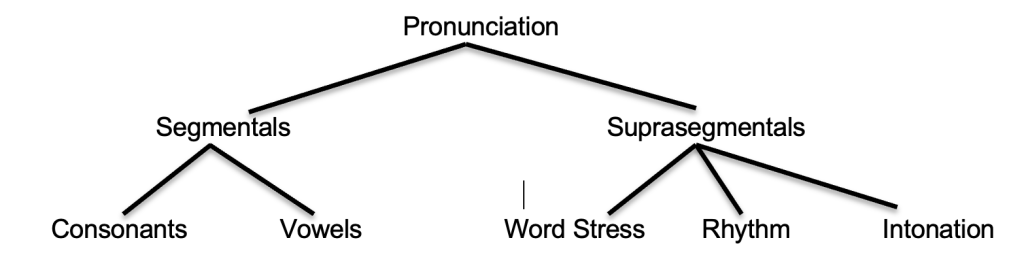

At a basic level, pronunciation can be divided into segmentals and suprasegmentals. Segmentals include vowel and consonant sounds. There are roughly 15 vowel sounds and 25 consonant sounds in American English, and different dialects of English have small but noticeable differences in how they pronounce vowels. These are among the most well-known aspects of English pronunciation. Sounds are represented imperfectly in the English spelling system, and it is common to mix up how we spell with the sounds. This is especially true with vowels. English has 5 or 6 vowel letters but almost 3 times as many vowel sounds. This means that our vowel letters have to do double or triple duty in representing sounds, and the results are not always easy to understand. For example, the <i> spelling can represent multiple sounds (such as like, hit, unique). Sometimes, English combines vowel letters, but these also do not transparently represent the same sound. The <ea> spelling is seen in the words heart, speak, steak, and heard, all of which are pronounced differently.

Suprasegmentals in English include word stress, rhythm, and intonation. Stress is a property of words, rhythm refers to stress in phrases, and intonation refers to the use of voice pitch to communicate meaning. The prefix ‘supra’ means ’above’ or ‘beyond the limits of,’ so suprasegmentals are those aspects of pronunciation that stretch out above many segmentals. For example, the word carrying has three syllables, but its stress pattern strongly stresses the first syllable followed by two less stressed syllables. On the other hand, the word replying has a strong stress on the second syllable, and the first and third syllables are less strongly stressed. Pronouncing either word with the opposite stress pattern will make it harder to understand.

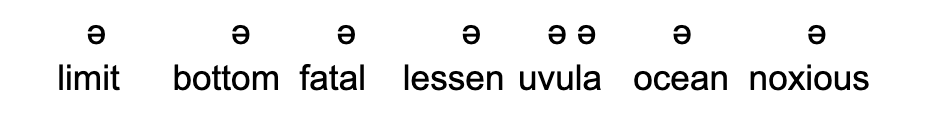

Suprasegmentals, though carefully divided from segmentals on the chart, influence the way that segmentals are pronounced. This is especially true for vowel sounds in unstressed syllables. The second syllable in each of the words below is unstressed, and no matter how the vowel is spelled, it is pronounced similarly, with the unstressed vowel schwa (written as [ə]). Schwa is the most common vowel in English for vowels that are not stressed, constituting about one in every three vowels in spoken language (Woods, 1978).

1.3 Pronunciation Teaching Goals: The Why of Pronunciation Teaching

Traditionally, teaching pronunciation had the goal of helping language learners become native-like in their pronunciation, a goal that has been called the Nativeness Principle (Levis, 2005). This means that learners should be able to pronounce everything in the ways that a typical native speaker does. This goal is quite attractive to many learners because being native-like in pronunciation seems to guarantee effective communication in the new language. Unfortunately, nativeness is exceedingly rare, especially for those who are learning a new language beyond childhood or in classroom environments. Age seems to limit the ability of most people to pick up on all the small details that signal whether someone is native in pronunciation. Native listeners are extraordinarily skillful in noticing that someone’s pronunciation does not match the local way of speaking, and as a result, trying to achieve native-likeness will almost always fall short. However, because native-likeness does not directly affect whether speakers will be successful communicators (Munro & Derwing, 1995), L2 learners can improve their pronunciation and communication by attending to the Intelligibility Principle.

Regarding goals, the Intelligibility Principle stands in contrast to the Nativeness Principle. Instead of seeking to be perfect in every detail, the Intelligibility Principle says that it is important to be successful on a limited set of pronunciation features that listeners use to understand L2 speakers. This means that pronunciation teaching will be more successful if we prioritize the errors that are more likely to cause misunderstanding (loss of intelligibility). In other words, not all details of pronunciation are important for intelligibility. Some, like the voiced interdental fricative [ð] (as in the, them, these, though), rarely seem to cause unintelligibility. In addition, this same sound is not always pronounced as [ð] by all native speakers of English, and L1 English listeners mostly understand variant pronunciations. In contrast, in a mispronunciation that affects intelligibility, some L2 learners of English struggle to pronounce the difference between /p/ and /b/ (e.g., pat-bat, lap-lab). In this case, the mispronunciation of /p/ and /b/ is much more likely to cause problems with intelligibility than the mispronunciation of [ð], and the Intelligibility Principle means that learners who have trouble with both will make much faster progress if /p/ and /b/ are prioritized.

Prioritizing intelligibility is important for all kinds of pronunciation features. For example, pronouncing word stress correctly is important in English because recognizing English words depends on recognizing the stress of the words. Word stress has been called the “islands of reliability” for listeners (Field, 2005), and both L1 and L2 listeners depend on these islands to navigate the stream of speech. This caused listeners in one study (Benrabah, 1997) to hear the word upset (stressed mistakenly on up) as absent. However, not all word stress errors cause a loss of intelligibility. For example, some L2 English speakers pronounce words like CONcentrate as concenTRATE, moving the main stress from the beginning of the word to the end. Because all the vowels are pronounced the same in both cases, English-speaking listeners do not struggle with stress errors in these types of words. So word stress should be prioritized, but only the word stress errors that cause problems.

1.4 Successful Pronunciation Teaching: The How of Pronunciation Teaching

Not only does teaching pronunciation include knowledge of pronunciation features and priorities, it also involves an understanding of how to apply that knowledge to promote student learning. This includes understanding typical ways to make English pronunciation make sense to L2 learners, whether that involves explaining new sounds and sound differences, helping learners to perceive new sounds accurately, or helping them learn how to actually produce sounds when they are concentrating on pronunciation or on meaning. One of the most well-known and usable frameworks for teaching pronunciation is the Communicative Framework of Celce-Murcia, Brinton and Goodwin (2010). The Communicative Framework has five components: Description and Analysis, Listening Discrimination, Controlled Production, Guided Production, and Communicative Production. The components can be used in any order, depending on the teacher’s goals or methods of teaching, but they can also be used in the order they are presented.

Description and Analysis recognizes that adult learners need to know why they are doing what they are doing. Unlike L2 children or first language learners, adult learners, because of their age, usually do not do well with figuring out language patterns simply by being exposed to input. They need explanations. They need visual help, such as IPA charts, sagittal diagrams, or computer simulations of speech to help them control their articulators. They need to know how new sounds are different from or similar to the sounds they are making. As a result, the role of Description and Analysis in pronunciation teaching is central to improvement.

Listening Discrimination, the framework’s second aspect, highlights perception’s importance in pronunciation learning. From very young ages, we all become very well attuned to the important sounds (phonemes) of our native languages, and we become increasingly unattuned to small differences between our language’s phonemes and how phonemes are pronounced in other languages. For example, English speakers recognize two phonemes, /t/ and /d/, which create different words such as toe/doe and let/led. Spanish also has /t/ and /d/ phonemes, but the ways that Spanish and English typically pronounce these sounds are different, as are the acoustic cues that allow native listeners in each language to process the sounds easily. And those differences are hard to hear for Spanish speakers learning English (or for English-speaking learners of Spanish).

Pronunciation is usually considered most important for speaking, and many teachers may be confused when we speak of listening discrimination as important for pronunciation. There are at least two reasons to pay attention to listening discrimination. First, many pronunciation problems occur because new languages have sounds that are difficult to hear accurately. Language learners bring their previous languages and ways of hearing the sounds in those languages when they learn to pronounce a new language. This means they will often hear inaccurately and not notice small, important distinctions in the new language that don’t exist in their existing languages. If they do not learn to notice and attend to these new differences, they are unlikely to ever pronounce them accurately. Second, part of pronunciation and part of intelligibility includes the listener being able to understand other speakers of the language in both careful and casual speech. Listening discrimination practice helps listeners communicate by noticing how other people’s pronunciation is used. As learners get better at knowing which sounds exist and hearing them, they are more able to communicate both in speech and in listening.

Controlled, Guided, and Communicative production differ in how much L2 learners can concentrate on pronunciation forms and meaning when they speak the new language. Controlled production exercises (e.g., read-aloud, listen and repeat) offer the most opportunity to attend to pronunciation form because the learner does not have to provide language spontaneously. At the opposite extreme, communicative production exercises focus on the communication of meaning. In this type of language activity, it is quite difficult for L2 speakers to concentrate on pronunciation because meaning is their dominant goal. Guided production, or what some have called “bridging exercises”, ask learners to attend to both pronunciation form and to meaning. In such exercises, meaning involves providing some language on one’s own with other language provided by the exercise (e.g., information gap exercises) so that learners can also partially focus on pronunciation forms. This book combines Guided and Communicative exercise categories because the distinction between the two is not always clear, nor is it always important. Both categories focus on meaning, and the difference between the two has to do with the extent to which they also attend to form, which is always central to pronunciation teaching.

These are not the only types of pronunciation activities, of course, as any examination of pronunciation activity books will show. Pronunciation activities can include games, physical movement, awareness-building exercises, the use of visuals, a focus on identity, ultrasound, computerized feedback, and many other creative approaches to instruction. However, the communicative framework is a useful template for understanding that most learners benefit from instruction that helps their brain comprehend the pronunciation goal, helps their ears learn to hear new sound categories, and helps their mouth to make new and unfamiliar movements.

1.5 Representing Sounds in English

Literate people are used to associating written language patterns with the sounds that they represent in spoken language, but no language has a perfect match between its spoken form and its written form. Spoken language varies depending on dialect, speech style, and social differences between speakers, but written language, especially more formal written language, shows very little variation, allowing us to read and understand writers who live far away from us or even those who have lived in a different time altogether (e.g., Shakespeare).

For learning pronunciation from written forms, it would be ideal to have a 1-to-1 correspondence between the way words are spelled and how the letters in the word are pronounced. Languages that approach the ideal, such as Spanish and Turkish, are considered to have “transparent” orthographies (spelling systems). Yet even in the most careful style of speech, transparent orthographies are never perfect. For example, the Spanish sounds spelled with <b, d, g> are always pronounced with the expected stop sounds [b, d, g] at the beginning of words. But when they occur between two vowel sounds, as in the words lobo, nada, agua, the <b, d, g> spellings represent different sounds: [β, ð, ɣ], which are fricatives made in the same area of the mouth as the expected stop sounds.

For other languages, these mismatches between spelling and pronunciation are much more frequent and make it difficult for L2 learners to know how an unfamiliar word should be pronounced. Languages like English, French, Irish Gaelic and Chinese have “opaque” orthographies that do not closely approach the 1-to-1 ideal that is helpful for using spelling systems for pronunciation learning. For example, the <ea> digraph in the words bear, beard, heard, heart, and speak are all pronounced as different vowels. In another example, the letter <c> has three different sounds in care, race, and racial. This mismatch (or multi-match) between spelling and sound is seen in a long poem called “The Chaos,” the first verse of which is reproduced below. In almost every line, there are (underlined) similar spellings that have different pronunciations. Sometimes, the same letters reflect different sounds, and sometimes, different letters reflect the same sound.

Dearest creature in creation, [kɹitʃɚ / kɹieɪʃən]

Study English pronunciation.

I will teach you in my verse [vɝs]

Sounds like corpse, corps, horse, and worse. [kɔɹps / kɔɹ / hɔɹs / wɝs]

I will keep you, Suzy, busy, [suzi / bɪzi]

Make your head with heat grow dizzy. [hɛd / hit]

Tear in eye, your dress will tear. [tɪɹ / tɛɹ]

So shall I! Oh hear my prayer.

In other words, navigating new spelling systems often gets in the way of accurate pronunciation. This seems especially true for English spelling. Even though English spelling is hard to navigate when learning to pronounce new words, it can be extremely helpful for learners to have a different writing system that reflects the ideal of 1-to-1 spelling and sound.

There are different ways to represent sounds, including symbols used by dictionaries. These symbols are often meant for native speakers and can sometimes be quite confusing for language learners. Merriam-Webster, for example, uses the symbol ā for the vowels in eight / ate and ä for the vowels in cot and bother. We will not use these symbols in this book. Instead, we will use symbols from the International Phonetic Alphabet, or IPA. The IPA is best known for its symbols used to represent consonant sounds and vowel sounds. Any single language has only a small subset of the possible sounds that are known to be meaning distinguishers in all languages in the world. North American English, for example, has about 25 consonant phonemes and 15 vowel phonemes. Spanish, on the other hand, has around 17 consonant phonemes and just 5 vowel phonemes.

Consonant Sounds

Most consonant sounds in the world’s languages, and all consonants in English, can be described by a combination of three characteristics: What touches in the mouth (i.e., place of articulation), how air from the lungs is released (i.e., manner of articulation), and what happens in the vocal folds (that is, whether sounds are voiced or voiceless). For example, in the consonant chart below, the /p/ has the characteristics of being bilabial, voiceless, and a stop (the air is stopped before it is released). It differs from /b/ in voicing and from /m/ in voicing and manner of articulation (the air in /m/ is released through the nose, making /m/ a nasal sound).

| MANNER | VOICING | Bilabial | Labiodental | Interdental | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Glotal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stop | Voiceless | p | t | k | ʔ | |||

| Stop | Voiced | b | d | g | ||||

| Fricative | Voiceless | f | θ | s | ʃ | h | ||

| Fricative | Voiced | v | ð | z | ʒ | |||

| Affricate | Voiceless | tʃ | ||||||

| Affricate | Voiced | dʒ | ||||||

| Nasal | Voiced | m | n | ŋ | ||||

| Lateral (Liquid) |

Voiced | l | ||||||

| Rhotic (Liquid) |

Voiced | r (ɹ) | ||||||

| Glide | Voiced | w | j | (w) |

Some sounds in the chart have parentheses around them. These are sounds that are noticeable markers of accent but are not meaningful. For example, [ɾ] is a tap sound (it touches behind the teeth very quickly) that is spelled by the <t> in kitty and <d> in ladder. In standard pronunciation for British English, on the other hand, the <t> in kitty is pronounced like a [t] and the <d> in ladder is pronounced as [d], where the tongue touches behind the teeth for a longer period of time. The glottal, or [ʔ] sound, on the other hand, can be heard at the beginning of each syllable in “uh, oh!” and for the <t> spellings in words like cotton and button.

Vowel Sounds

The spelling and sound mismatch is particularly large for English for vowels. Written English has five (or six, counting <y>, which usually behaves like the letter <i> when it is a vowel) vowel letters, but North American English has around 15 vowel sounds. Descriptions of British English describe closer to 20 vowel sounds. In addition, the written symbols <a, e, i, o, u> are used for different sounds than the same-looking phonetic symbols. Having only five vowel letters to represent 15 vowel sounds means that English spelling also doubles up on vowel letters to represent sounds. For example, the spellings <ea>, <ou>, <ai, ay>, and <oo> are frequent in English spelling, but like single letters, they also represent different sounds.

|

Spelled symbol

|

Sound Values

|

|---|---|

|

<ea>

|

speak [i], steak [eɪ], heart [ɑ], heard [3r]

|

|

<ou>

|

rough [ʌ], bough [aʊ], cough [ɑ] or [ɔ], coupon [u], though [oʊ] |

|

<ai>, <ay>

|

maid [eɪ], plaid [æ], said [ɛ], Hawaiʻi [aɪ], play [eɪ]

|

|

<oo>

|

cook [ʊ], food [u], blood [ʌ] |

The vowel sounds connected to English spelling are also affected by stress patterns. Words of two syllables or more usually have at least one unstressed syllable, and overwhelmingly, these unstressed vowels are pronounced with the same vowel sound. This sound is called schwa, and it is represented by the symbol [ə] which sounds like “uhh”, the sound made when people don’t know what to say. The schwa sound can be spelled with any vowel letter or combination of letters. For example, schwa occurs n the second (unstressed) syllables of each of the following words: common, toxic, minus, petal, noxious, pellet, nation, ocean. Mismatches between letters and sounds and the effect of stress make it important for us to have symbols that directly represent vowel sounds in English. These symbols are shown in the special phonetics chart for vowels below. Vowels have different features than consonants, so they need a different chart that shows where the tongue is (Front, Central, Back), how open the jaw is (High, Mid, Low), and whether the lips are rounded (in English, the back vowel /u/, /ʊ/, /oʊ/, /ɔ/, and /ɔɪ/ are rounded).

| Vowel features | Front | Central | Back |

|---|---|---|---|

| High | /i/ feed /ɪ/ fib |

/u/ boot /ʊ/ book |

|

| Mid | /eɪ/ fade /ɛ/ fed |

/3r/ /ər/ curd keeper /ʌ/ /ə/ cut about |

/oʊ/ boat |

| Low | /æ/ fad | /ɔ/ bought (can also be said /ɑ/) /ɑ/ cot (can also be said /ɔ/) |

|

| Diphthongs | /aɪ/ cried /aʊ/ cloud |

/ɔɪ/ boy |

There is one final important issue to mention for North American English: the cot-caught merger. The vowels in cot (/ɑ/) and caught (/ɔ/) were historically distinguished from each other in North America. For some dialects, they still are. But for at least half of the US population, there is no difference in pronunciation for these words, with /ɑ/ the usual pronunciation. In Canada, there is also no difference, but /ɔ/ is the normal pronunciation. Fortunately, this merger almost never causes misunderstandings, so it is fine for language learners to use whichever vowel is most comfortable for them.

1.6 References

Benrabah, M. (1997). Word-stress–a source of unintelligibility in English. International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching (IRAL), 35(3), 157-165. https://doi.org/10.1515/iral.1997.35.3.157

Celce-Murcia, M., Brinton, D. M., & Goodwin, J. M. (2010). Teaching pronunciation: A course book and reference guide. Cambridge University Press.

Derwing, T. M., Munro, M. J., Foote, J. A., Waugh, E., & Fleming, J. (2014). Opening the window on comprehensible pronunciation after 19 years: A workplace training study. Language Learning, 64(3), 526-548.

Field, J. (2005). Intelligibility and the listener: The role of lexical stress. TESOL quarterly, 39(3), 399-423. https://doi.org/10.2307/3588487

Flege, J. E. (1995). Second language speech learning: Theory, findings, and problems. In W. Strange (Ed.), Speech perception and linguistic experience: Issues in cross-language research, (pp. 233-277). York Press.

Jenkins, J. (2000). The phonology of English as an international language. Oxford University Press.

Lee, J., Jang, J., & Plonsky, L. (2015). The effectiveness of second language pronunciation instruction: A meta-analysis. Applied Linguistics, 36(3), 345-366. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amu040

Levis, J., & Sonsaat, S. (2017). Pronunciation teaching in the early CLT era. In O. Kang, R. Thomson & J. Murphy (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of contemporary English pronunciation (pp. 267-283). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315145006-17

Munro, M. J., & Derwing, T. M. (1995). Foreign accent, comprehensibility, and intelligibility in the speech of second language learners. Language Learning, 45(1), 73-97. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-1770.1995.tb00963.x

Scovel, T. (2000). A critical review of the critical period research. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 20, 213-223. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0267190500200135

Levis, J. M. (2005). Changing contexts and shifting paradigms in pronunciation teaching. TESOL Quarterly, 39(3), 369-377. https://doi.org/10.2307/3588485

Thomson, R. I., Derwing, T. M., & Munro, M. J. (2024). How long can naturalistic L2 pronunciation learning continue in adults? A 10-year study. Language Awareness, 33(2), 201-223. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658416.2023.2227559

Zielinski, B. W. (2008). The listener: No longer the silent partner in reduced intelligibility. System, 36(1), 69-84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2007.11.004

Zuengler, J. (1989). Identity and IL Development and Use1. Applied Linguistics, 10(1), 80-96. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/10.1.80