Suprasegmentals

9 Intonation: Tune

John M. Levis

- To familiarize teachers with how intonation is signaled in English

- To enhance teachers’ ability to teach intonation to students

- To demonstrate why intonation is important in promoting intelligible speech

- To introduce teachers to how intonation adds meaning to different grammatical structures

- To provide exercises for producing and perceiving final intonation

9.1 What is intonation?

Intonation refers to the “distinctive use of patterns of pitch, or melody” to communicate meaning in a language (David Crystal, reported in Chun, 2002, p. 4). Intonation, in this definition, involves the use of pitch to communicate a speaker’s stance toward what they are saying. Intonation can also be defined in terms of distinct linguistic categories. Final intonation refers to rising vs. falling final pitch or combinations of rising and falling pitch that communicate meaning. Intonation contributes meaning to individual phrases and sentences, but intonation is particularly important at the discourse level (in how the meanings expressed by sentences fit together). For example, when speakers (especially younger speakers) sometimes use frequent rising pitch at the ends of their phrases while they are talking at length about a topic, a phenomenon called Uptalk (Warren, 2016) or Upspeak (Bradford, 1997), they are using this intonation for a discourse purpose. The rising intonation engages listeners and also tells them that the speaker is not yet finished with their narration. In addition, the use of Uptalk can serve as a marker of group identity. Of course, it also can be annoying to some listeners who accuse speakers of talking in questions, even when they are making statements, but the use of Uptalk serves communicative purposes in how some groups of people communicate.

There are many intonation patterns that have been described for English, such as the calling contour, which has a high pitch on the stressed syllable, then steps down to a low pitch at the end of the name (e.g., AlexANder! SUsan! JOhn!) or the children’s chant (Johnny has a girlfriend!), which has a set of pitch steps that almost everyone recognizes as being unpleasantly teasing.

Calling Contour

AlexANder! SUsan! JOhn!

Children’s Chant

Johnny has a girl friend.

These stylized intonation contours were also important for researchers in learning how to describe English intonation (Ladd, 1978; Liberman, 1975), but for learners of English, and for teachers, there are only a few patterns that cover almost everything they need. These patterns include rising, falling, falling-rising, and level intonation. These different patterns can be represented by arrows pointing in the direction that the pitch moves at the end of the spoken sentence. Rising intonation has an upward movement () and falling intonation a downward movement (). Falling-rising combines these two movements, and level intonation has no movement. The intonation expert David Brazil says that level intonation is used when a speaker is treating the language as an object, not as real communication. For example, if someone has said the same thing many times (e.g., in taking money at a ticket booth), they may sound rather bored, with lots of level intonations.

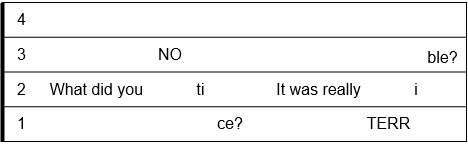

Final intonation starts from the final prominent syllable and continues to the end of each spoken sentence. In the example sentences, both start with a prominent syllable (in CAPS) then continue with falling (on NOTice) or rising intonation (on TERRible).

Intonation is signaled by several acoustic parameters, including duration, intensity, and pitch. Pitch is the most important. For teaching, it is helpful to simply help learners pay attention to pitch. Pitch is noticeable to most learners (even though some will struggle to name what they are hearing). Pitch is measured via the fundamental frequency, or F0, of speech. Listeners hear and react to intonation more globally, paying attention to how pitch highlights certain words (see Chapter 8), how pitch range seems more extreme or compressed than usual for a speaker, and how pitch moves at the ends of spoken sentences. This pitch movement at the ends of spoken sentences is what we are calling final intonation or tune.

9.2 Why is Intonation Important?

Intonation is especially important for teaching and learning because it adds an independent source of meaning to the messages that speakers communicate. This meaning can tell listeners whether speakers are asserting information as being true or false, whether they are open to multiple answers or expect one answer, whether they are uncertain, or if their attitude toward what they are saying is detached and uncommitted.

Every spoken sentence has to end with some type of intonation. When combined with other spoken sentences, the blend of intonation patterns used by speakers makes it easier or harder for listeners to understand what is being said, causes listeners to judge speakers positively or negatively, and supports or conflicts with other aspects of meaning that are communicated. Intonation helps listeners understand whether speakers are saying something that needs a response, whether speakers are still talking and intend to say more, or whether speakers are asserting something that does not require a response.

Intonation occurs at the end of every spoken phrase or sentence. Listeners expect that intonation will help them understand what speakers are trying to say. In one study of the teaching language of Chinese teaching assistants, or TAs, in a US university, Lucy Pickering (2001) found that the Chinese TAs used a lot more falling intonation than American TAs when they lectured. The undergraduate students found the Chinese TAs hard to listen to because they seemed to be asserting too much information. The greater use of rising intonation by the American TAs, however, made the undergraduates feel that the teachers were more approachable and that the information they presented was more accessible to them.

9.3 Intonation and Meaning

Although intonation creates a special and independent type of meaning in speech, it combines with other aspects of language to create meaning. Meaning is also created by speakers by their choice of words, the grammar they use, and how they pronounce things, including their intonation. The meaning of intonation has been described in terms of speaker attitudes (Pike, 1945) or emotions (Banziger & Scherer, 2005), but these types of meaning are too vague to be of tremendous use in teaching (Levis, 1999).

Intonation has an indirect connection to grammar (Levis, 1997), with both areas of language structure contributing to speech’s meaning. In other words, grammar and intonation have independent contributions to meaning. Different types of intonation contours can be used with all types of grammatical structures (incomplete sentences, declarative, yes/no, and WH questions, etc.) depending on the types of meaning that speakers want to communicate. Similarly, every grammatical structure can be spoken with different intonations, giving speakers a great deal of flexibility in communicating meaning. Whether your voice rises or falls can add different meanings to your message, especially with incomplete sentences or statements, both of which are more flexible in terms of intonation’s meaning.

With other grammatical structures, such as questions, intonation choices add subtle yet important meanings that can change the kind of message listeners understand. For example, on a yes/no question, rising intonation may communicate openness to any answer, while falling intonation may communicate an expectation that the speaker already knows the answer (Thompson, 1995). In both cases, the speaker has asked the same yes/no question, but the intonation suggests whether the speaker expects a certain type of answer.

9.4 Common Intonation Challenges

Intonation can be hard to learn in a second language, and teachers may find it challenging to teach. Unlike phonemes, intonation is not represented by our writing system, except very indirectly through punctuation choices. It is also sometimes hard to identify, even for native speakers who use it successfully. For example, when I (John) was first learning about intonation, I would say that pitch rose when it fell and vice versa. Rising-falling intonation I could usually identify because of meaning, but it took a long time for me to feel comfortable with being able to identify pitch movements. Some learners of English may have the same challenges.

Other challenges with intonation happen when there is a mismatch in either form or meaning between a learner’s native language and English. It is important to remember that intonation is similar to vowel and consonant sounds in that it communicates meanings that may be hard for language learners to hear if their own language doesn’t make use of the distinction that is important in English. Madalena Cruz-Ferreira demonstrated this in a 1987 study of Brazilian Portuguese and English L2 learners who identified whether two sentences had the same intonation, and whether differences in intonation had different meanings.

Cruz-Ferreira found that listeners were successful in identifying differences that were the same across languages, such as the use of intonation to create thought group differences, as in the next example in which phrase grouping leads to a different interpretation of who “They” refers to.

They’ve left the children vs. They’ve left / the children.

In situations in which English uses a form that has no parallel meaning in Portuguese, such as the falling-rising intonation contour on “not…any” sentences, language learners struggled to identify or interpret the sentences. The fall-rise here means that they admit students but are selective, as if the sentence said “just any.” The fall means they don’t admit students at all.

They don’t admit ANy students (fall-rise) vs. They don’t admit ANy students (fall)

A learner’s native language may also use the same form as English, but for a different meaning. In such a case, the learner hears the intonation perfectly well but cannot successfully interpret its meaning. Cruz-Ferreira gives examples of this for English speakers of Portuguese as an L2Finally, in another case where learners may not be able to interpret meanings when they hear differences, Portuguese speakers could not interpret attitudes behind differences in pitch range. The sentence “Where have you left your KEYS?”, when spoken with a flat pitch range on KEYS, had a grumpy overtone, but when spoken with an extended pitch range, it was heard as a neutral question. The Portuguese speakers heard the difference in form but did not understand its meaning.

9.5 Tips for Teaching Intonation

Intonation is best taught when its forms and meanings are noticeable to language learners. Because the pitch movements of final intonation start after the pitch movement of prominence, it can be challenging for language learners to distinguish the two movements. In the sentence below, the pitch rises on the prominent syllable, GO, then falls to the end of the sentence. Heard together, learners may notice the rise on GO but not the fall to the end of the sentence, or may hear both pitch movements as a single unit. In the British tradition, this would be interpreted as a falling nuclear tone.

I wanted to GO there with her.

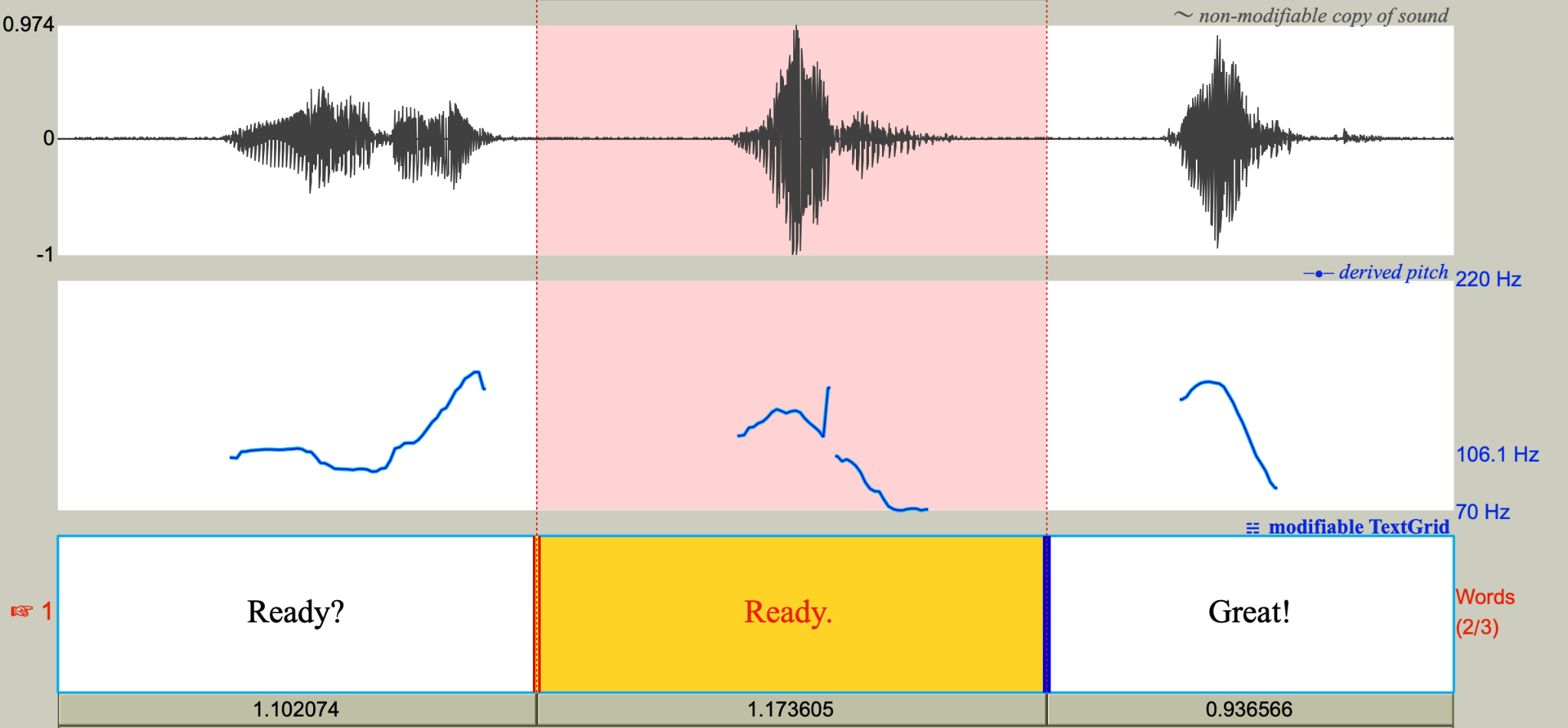

Because of this potential conflict, we find it easiest to introduce final intonation using single words, or short sentences, in which the Prominence and Final Intonation are heard as one unit, and the final Intonation is easy to hear, as in the dialogue. (These ideas for using short sentences are based on a still excellent 1971 article on teaching intonation by Virginia French Allen.) The question mark on the first word reflects rising intonation, whereas the next two “short sentences” have to be spoken with falling intonation. Such use of short sentences also reflects how many spoken sentences actually occur in English, in which speakers don’t use complete sentences when they are not needed.

A: Ready?

B: Ready.

A: Great!

9.6 Technology Corner

There is abundant research evidence that visualizing pitch helps language learners. Since the early 1980s, studies have shown that visualizing the acoustic movement of pitch leads to better learning of intonation by language learners (e.g., de Bot & Mailfert, 1982). For example, using Praat, one of many freely available means to visualize pitch, the dialogue above could look like Figure X. The first line shows the rising intonation of Ready? and the next two utterances show falling intonation.

Having a program that further allows learners to match their own production to a model production provides feedback on intonation that leads to better learning (e.g., Hardison, 2004; Jiang & Chun, 2023).

A more low-tech approach to technology is the use of kazoos, as described in the prominence chapter. Kazoos, which mask the segmental content of utterances, are excellent in making any kind of pitch movement noticeable. A number of studies have demonstrated that language learners may pay more attention to the words and grammar than to how sentences use suprasegmentals to communicate differences in meaning. For example, Pennington and Ellis (2000), played sets of words and phrases to Cantonese speakers that differed in intonation. The listeners, who were used to paying attention to pitch in their native language, were quite unsuccessful in hearing intonation in English. Even when they were told what to listen for, they remained unsuccessful in noticing most of the intonation differences, at least in the short time of the study.

9.7 ProFUNciation – Why Intonation Matters

In 1982, John Gumperz, a prominent sociolinguist in the UK, reported on a situation he was asked to investigate in a British Air cafeteria. At that time, the cafeteria workers served other airline employees who were responsible for the maintenance and flying of the planes. These employees were angry at the cafeteria employees, who they thought were rude. The cafeteria servers, who were mostly Indian and Pakistani immigrant women, were angry at the employees who came through their lines, accusing them of being racist. Gumperz observed and listened, and found that the center of the hostility had to do with intonation. When the servers offered to those going through the lines things like gravy (for their meat or potatoes), they used falling intonation. Those going through the line interpreted this falling intonation as saying “Here is gravy, take it or leave it” whereas a rising intonation would have sounded polite, e.g., “Would you like gravy?” The servers, on the other hand, thought they were being polite. In their native languages, it was polite to offer food using falling not rising intonation. What is interesting is that no one until Gumperz realized that this was an intonation problem. Everyone thought it was a social problem, and the people on both sides of the problem understood the conflict as a reflection of their deep-seated social beliefs about the other people involved in the conflict.

In another example, Bob Ladd, an internationally known intonation researcher (he is from the US but has taught for years in the UK), told a story one time of being at a restaurant in the US. At the end of the meal he asked “Can I have the check, please?” with a polite falling-rising intonation – Polite, that is, in the UK. His server reacted negatively to the request as insistent and pushy, like he had already asked before and was now annoyed. Ladd soon realized what he had done, and he changed his request to rising intonation in line with American norms. Again, the intonation was not heard by the listener as a pronunciation error but as a social failing. This indicates that wrong intonation may cause more serious problems with intelligibility than just not understanding a word!

ProFUNciation – Video

9.8 Activities

Description/Analysis

Exercise 9-1. Intonation Forms and Functions

Background. Final Intonation is the use of pitch variations to communicate meaning. Intonation has different forms (which direction the pitch moves) and functions (what the form means). Two of the most common final intonation tunes are rising and falling.

Directions: Listen to how the pitch changes at the end of each sentence,

I’m going to China! (F) Did you hear? (R)

You’re going to China? (R) When? (F)

Explanation: Final Intonation has a number of tunes that are common in English.

- A movement in pitch up (rising), down (falling) or a combination of these pitch movements (falling-rising). Pitch can also not move (level).

- Intonation is the end of each spoken phrase or sentence

Final Intonation communicates different types of meaning in English.

- It calls attention to the end of the spoken sentence

- It signals openness (rising) or assertion (falling)

- It can signal incompletion (falling-rising, level) or completion (fall, rise) of an utterance

Exercise 9-2. Intonation contours in English

Directions: Listen to each short sentence and notice the way final intonation is different.

| Rising | Falling | Falling-Rising | Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ready? | Ready. | I’d like to help… | I don’t like that |

Exercise 9-3. Final Intonation

Directions: The teacher uses the information to describe intonation. The numbers represent relative levels of pitch (1 = lowest, 2 = normal, 3 = highest). The media includes recordings of each example sentence.

Final intonation in English usually follows one of 5 patterns. Not all are equally important. Most can occur on a wide variety of grammatical structures (such as statements., yes/no questions, WH questions, incomplete sentences). The numbers refer to pitch levels: 2 is normal pitch, 3 is higher, and 1 is lower.

2-3-1 (Rising) falling: This pattern rises to a higher pitch on the prominent syllable, then falls to a relatively low pitch. Example sentence: He didn’t do it.

2-3 Rising: This pattern rises to a high pitch at the end. Example sentence: He didn’t do it?

2-3-1-2 Falling-Rising: This pattern gives a sense of incompleteness, of not being finished with the utterance. Example sentence : He didn’t do it…

2-2 Level: This is a level pattern. It sounds bored or uninvolved. It can also signal incompleteness. Example sentence : He didn’t do it —

Listening Discrimination

Exercise 9-4. Identifying intonation (adapted from Rita Wong, 1987)

Directions: List the following words on the board, or use others. Make your own list that is marked with either rises or falls for each word. Read and ask the students to determine whether the pitch is rising or falling. Mark an up or down arrow on the board for the correct answer.

ready

yes

no

problems

babysitter

what

trouble

problems

some

coming

stay

maybe

Exercise 9-5. Rising and Falling intonation of Wh questions

Directions: Listen to the two dialogues. What is different about the intonation of Where in the dialogues?

A: So what are you going to do for Christmas break?

B: I’m going to California.

A: Where?

B: San Francisco

A: So what are you going to do for Christmas break?B: I’m going to California.

A: Where?

B: California.

Where? with rising intonation means ___________________

Where? with falling intonation means __________________

Controlled Practice

Exercise 9-6. Short Sentence Dialogues (Rising and Falling intonation)

Background: Introducing intonation is most successful with short sentences because the communicative power of intonation is most noticeable in these short sentences. These types of dialogues are easy to write, and they reflect how people who know each other well usually speak because they include only enough information for their meaning, letting intonation carry part of the communication.

Directions: In pairs, read one of the dialogues. Decide how the intonation for each line is pronounced and why. Then read the dialogue for the class.

Situation: Two college students are in the library. A is at a table and B comes up to speak to A.

- A: Studying?

- B: Yeah.

- A: What?

- B: Chemistry.

- A: Hard?

- B: No. Boring.

Situation: Mr. Brown and his family arrive at a restaurant. The host/hostess greets them.

- A: Reservations?

- B: Yes.

- A: Your name?

- B: Henderson.

- A: Outside?

- B: Please.

- A: Follow me.

Situation: Roommates are getting ready to go out..

- A: Finally. I’m ready!

- B: Really?

- A: Sure. Come on.

- B: Where?

- A: The movies.

- B: Which theater?

- A: Don’t know. Movies 12?

- B: Too expensive.

- A: North Grand?

- B: Sure. Let’s go.

Situation: A customer is in a coffee shop. The waiter comes up to serve him.

- A: Coffee?

- B: Pardon?

- A: Cup of coffee?

- B: Sure.

- A: Milk?

- B: Let me think…Black, please.

Situation: A husband and wife are getting ready to go out.

- A: Coming?

- B: Almost.

- A: When?

- B: Soon.

- A: Soon?

- B: Five minutes?

- A: Can you hurry?

- B: I’m trying.

Exercise 9-7. Intonation of WH Questions

Directions: Use the short dialogues to practice the different forms and functions of intonation for Wh questions. Person X starts. Then person Y chooses either rising or falling intonation, and Person X has to respond with the correct response. If the response is not what Person Y intended, discuss where things went wrong.

Dialogue Set A

X: They moved their headquarters near campus.

- Y: Where? (R)

- X: Near campus.

- Y: Where? (F)

- X: On Western Avenue.

Dialogue Set B

X: I left it on the bus.

- Y: Where did you leave it? (R)

- X: On the bus.

- Y: Where did you leave it? (F)

- X: Under my seat.

Dialogue Set C

X: The next home game is this weekend.

- Y: When? (R)

- X: This weekend.

- Y: When? (F)

- X: On Saturday afternoon.

Dialogue Set D

X: I’ll call you in the morning.

- Y: When? (R)

- X: In the morning.

- Y: When? (F)

- X: Around 9:30.

Dialogue Set E

X: A hurricane hit the West Coast.

- Y: Where? (R)

- X: The West Coast

- Y: Where? (F)

- X: California.

Guided and Communicative Practice

Exercise 9-8. Conversation practice (Rising and falling intonation)

Directions: Practice having a conversation with another person. Use short sentences of one or two words each. Do not write your conversation down. One person starts the conversation with one of the words under “Openers”. The other person responds with an appropriate word from any of the columns. (You may also use other words, especially names.) Continue the conversation (using your own words) until someone says something that does not make sense or until someone uses a long sentence.

Remember that a change in intonation will change the meaning of your short sentences. For example, “Ready” with rising intonation means “Are you ready?” With falling intonation, “Ready” means something like “I’m ready”.

Openers

- Coming

- Going

- Ready

- Trouble

- Fun

- Happy

- Difficult

- Easy

- Good

- Bad

- no

- Yeah

- Kind of

- Almost

- Soon

- Later

- Come on

- Not really

- Really

- Very

Other words

- Boring

- Why

- When

- What

- Where

- Who

- How long

- Not yet

- Hurry

- Quick

- Because

- Don’t know

- To class

- Home

- My grade

- Movies

- Chemistry

- 5 minutes

- OK

- Sure

Example Conversations

Conversation 1

- Student 1: Ready

- Student 2: Really?

- Student 1: Sure.

- Student 2: Come on

- Student 1: Where?

- Student 2: Movies.

- Student 1: What?

- Student 2: Don’t know

Conversation 2

- Student 1: Coming?

- Student 2: Almost.

- Student 1: When?

- Student 2: Soon.

- Student 1: Soon?

- Student 2: 5 minutes?

- Student 1: Hurry

- Student 2: OK

Exercise 9-9. Twenty Questions

Directions: This is a challenge in which one person thinks of something or someone, and the other person has to ask yes/no questions to try to figure out what the first person is thinking about.

Example: I’m thinking of someone in this room. You ask questions until you can guess who it is. Your questions must begin with IS/ARE.

Examples: Is it a man/woman? Are her eyes blue? Are her shoes red? Is her hair blonde?

Exercise 9-10. Branching Dialogue: WH Questions

Background: This dialogue has challenges because each person does not see the other person’s sentences. They have multiple choices for their own response, but the conversation has to make sense.

Speaker A

Directions: Speaker A begins the dialogue. Speaker B chooses a response with a sentence on their paper. Speaker A listens and chooses the most appropriate response as a reply. Speaker B then chooses the most appropriate response, and so on. After finishing, try the dialogue again with different responses or switch roles. Some WH questions have rising intonation and some have falling.

A: I’m leaving tomorrow to visit my friend.

B:

A1: My friend. I told you about her, didn’t I?

A2: Linda. I told you about her, didn’t I?

B:

A1: Linda. She lives near Washington. I’ll be there for a week.

A2: Yeah. We’ll probably go to Washington on Friday.

B:

A1: A week or so. I think I’ll come back next Thursday.

A2: I’m sorry. I wasn’t listening. WHAT did you ask me again? (Please repeat)

B:

A1: The afternoon. There’s a really great Indian restaurant we want to go to. It’s got great food! And it’s pretty cheap, too!

A2: We’re going to the Smithsonian, and it’s really big.

A3: Oh no, I forgot. I guess I’ll have to come back earlier.

B:

Speaker B

Directions: Speaker A begins the dialogue with a sentence on their paper. Speaker B chooses one response. Speaker A chooses the most appropriate response as a reply. Speaker B then chooses the appropriate response and so on. After finishing, try the dialogue again with different responses or switch roles. Some WH questions have rising intonation and some have falling.

A:

B1: Who? (Please repeat. I didn’t hear you)

B2: Who? (Please give me more information about your friend)

A:

B1: Oh, yeah. I remember now. What’s her name?

B2: Oh, yeah. She lives in Washington, doesn’t she?

A:

B1: How long will you be there? (Speaker B is surprised)

B2: When? In the morning or in the afternoon?

A:

B1: Did you remember that there’s an honor society dinner next Wednesday?

B2: Are you going to Washington in the morning or the afternoon?

B3: That sounds like fun. Where in Washington will you go?

A:

B1: I’ve never been to the Smithsonian. I hear you can stay there for days.

B2: Sounds wonderful! I love Indian food. You’ll have to tell me about it.

B3: The dinner doesn’t start until 7:00. You can leave around lunch, and still get back in time.

9.9 References

Allen, V. F. (1971). Teaching intonation, from theory to practice. TESOL Quarterly, 5(1), 73-81. https://doi.org/10.2307/3586113

Bänziger, T., & Scherer, K. R. (2005). The role of intonation in emotional expressions. Speech Communication, 46(3-4), 252-267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.specom.2005.02.016

Bradford, B. (1997). Upspeak in British English. English Today, 13(3), 29-36. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0266078400009810

Chun, D. M. (2002). Discourse Intonation in L2. John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/lllt.1

Cruz-Ferreira, M. (1987). Non-native interpretive strategies for intonational meaning: An experimental study. In J. Leather & A. James (eds.), Sound patterns in second language acquisition (pp. 103-20). https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110878486-007

De Bot, K., & Mailfert, K. (1982). The teaching of intonation: Fundamental research and classroom applications. TESOL Quarterly, 16(1), 71-77. https://doi.org/10.2307/3586564

Hardison, D. M. (2004). Generalization of computer assisted prosody training: Quantitative and qualitative findings. Language Learning & Technology, 8(1), 34-52.

Jiang, Y., & Chun, D. (2023). Web-based intonation training helps improve ESL and EFL Chinese students’ oral speech. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 36(3), 457-485. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2021.1931342

Ladd, D. R. (1978). Stylized intonation. Language, 54(3), 517-540. https://doi.org/10.1353/lan.1978.0056

Levis, J. M. (1999). Intonation in theory and practice, revisited. TESOL Quarterly, 33(1), 37-63. https://doi.org/10.2307/3588190

Liberman, M. Y. (1975). The intonational system of English. (Doctoral dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology).

Pickering, L. (2001). The role of tone choice in improving ITA communication in the classroom. TESOL Quarterly, 35(2), 233-255. https://doi.org/10.2307/3587647

Pike, K. L. (1945). The intonation of American English. University of Michigan Press.

Thompson, S. (1995). Teaching intonation on questions. ELT Journal, 49(3), 235-243. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/49.3.235

Warren, P. (2016). Uptalk: The phenomenon of rising intonation. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9781316403570

Wong, R. (1987). Teaching pronunciation: Focus on English rhythm and intonation. Language in Education: Theory and Practice, No. 68.