Suprasegmentals

8 Prominence

John M. Levis

- To familiarize teachers with how prominence is signaled in English

- To enhance teachers’ ability to teach prominence to students

- To demonstrate why prominence is important in promoting intelligible speech

- To introduce teachers to how word categories function in attracting prominence

- To provide exercises for producing and perceiving prominence

8.1 What is prominence?

Prominence is a special blend of intonation and stress. It gives English speech a characteristic sound shape and simultaneously communicates several distinct types of discourse meanings. Prominence has a number of names in discussions of English pronunciation, including sentence stress (Grant, 2012), primary phrase stress (Dickerson, 1989; Hahn, 2004), nuclear stress (Jenkins, 2000), pitch accent (Ladd, 1996), highlighting (Kenworthy, 1987), and focus (Levis & Grant, 2003).

Prominence is part of the pronunciation of phrases (or thought groups). We speak in phrases, and the end of one phrase (perhaps to take a quick breath) is succeeded by a new group whose words include repeated and new content. Typically, there is one prominent syllable per thought group. The prominence can be signaled by an upward or downward movement in pitch on the stressed syllable of the prominent word, greater length on that syllable, and/or clear articulation of the vowels and consonants. Prominence typically occurs near the end of the thought group, most often on the last content word (noun, verb, adjective, or adverb). In the sentence below, a phrase from a personal narrative, the prominent syllable on the word “wearing” follows the typical placement of prominence and is marked primarily by syllable length and more careful enunciation.

“…what the students at their school were WEARing.”

Why is prominence important in English pronunciation?

Prominence is important because it helps listeners follow the developing message of a speaker. The common themes of speakers and listeners are created by using the voice to emphasize particular words and de-emphasizing words that are no longer as important. This helps listeners to understand better and to feel more positively toward the speaker. Laura Hahn, in her 2004 study using three versions of a short lecture given by a Korean L1 teaching assistant, showed that undergraduate students remembered more of the message when prominence was placed on the expected words in the lecture than when it was misplaced or not used at all. She also found that the students liked the lecturer more when their prominence was correctly pronounced.

In another influential research study, Jennifer Jenkins found that prominence was important for intelligibility when two nonnative (or bilingual) speakers of English were speaking to each other. In her set of core features for pronunciation teaching, prominence placement was the only suprasegmental feature that was part of the core. These findings mean that prominence is critically important for both native and nonnative listeners, and that expected placement of prominence makes both native and nonnative speakers more intelligible when they speak.

Where to place prominence – The Default Setting

Prominence creates a normal sound shape for English speech. Listeners expect prominence in certain places as a default placement, and speakers almost always place prominence in those places. (Almost always…having an expected placement also helps call attention to special meanings for prominence when it does not fall where it is expected.) The expected placement means that the prominent syllable is almost always near the end of a phrase, often the last word of a phrase, and it is the beginning of a final pitch pattern at the end of the phrase. In 1969, the famous linguist David Crystal discovered that this default pattern for prominence occurred 90% of the time in normal English speech. The prominent syllable is also almost always in a content word (e.g., noun, verb, adjective). So, the default pattern says that the last content word in a phrase will receive prominence. For the sentences preceding the audio snippets below, the CAPITALIZED syllable receives the prominence.

“The highlands of Scotland have roaming CATtle.”

“Is that the last movie that made you LAUGH?”

“It’s absolutely GORgeous there!”

“Companies do that to save money QUICKly.”

Listen to the sentence and identify where to place prominence.

8.2 Representing Prominence

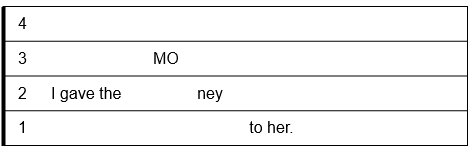

A non-technological way of representing prominence is to visualize it as part of a modified musical staff with different pitch levels from 1 (low) to 4 (high).

Few teaching materials emphasize this default prominence pattern even though it dominates normal English speech. But it is worth teaching it by helping students to hear it, to expect it, and to produce it in their own speech. It’s what listeners expect to hear and leads to easy comprehensibility.

Sometimes, as in sentence 4, other words and syllables follow the prominent syllable. These words need to be pronounced with a low pitch. We call this de-accenting, and it’s a very important part of using prominence correctly because it helps make the prominent syllable noticeable by not calling attention to possible competitor words that come later in the phrase.

Where do you expect the prominence in these sentences? Underline the word that you think will receive prominence in each phrase.

“This food is nutritious and delicious.”

“It all worked out pretty well.”

“He said he didn’t do it.”

“It was hard because of all the craziness there.”

In summary, default prominence placement generally follows well-defined patterns that involve

- word types (content words are most likely to have prominence)

- placement in the phrase (prominence is typically toward the end of the phrase)

- stress placement (primary stressed syllables in longer words will be prominent)

These patterns show up in longer stretches of spoken language as well, not just in individual sentences. This TED talk, “How students of color confront imposter syndrome,” starts in this way (with / marking the spoken phrases that the speaker uses). The final content word in each spoken phrase is underlined, and almost all of these receive prominence. This is how English speech is shaped. Only four phrases have prominence before the last content word, and two of these are compounds (building stoops, domino playing).

So, my journey began / in the Bronx, New York, / in a one-bedroom apartment, / with my two sisters / and immigrant mother. / I loved our neighborhood. / It was lively. / There was all this merengue blasting, / neighbors socializing on building stoops / and animated conversations / over domino playing. / It was home, / and it was sweet. / But it wasn’t simple. / In fact, / everyone at school knew the block where we lived, / because it was where people came to buy weed / and other drugs. / And with drug-dealing comes conflict, / so we often went to sleep / to the sound of gunshots. /

When learners can shape their English speech in this way, they will immediately become more intelligible because their speech will fit with the ways that listeners are used to listening.

8.3 Marking New Information and Deaccenting Given Information

Prominence placement is sensitive to the information value of words in discourse. In a well-known pedagogical example of prominence placement in English, Linda Grant wrote a short text about pollution for her pronunciation book, Well Said (2012, p. 114). The text is shown below, with / marks dividing thought groups. If we just look at three repeated words in the text, pollution, scientists, and problem, we see that normal prominence placement initially falls on pollution in the first phrase. After that, pollution ends the 3rd and 5th thought groups, but does not receive prominence again. Instead, the prominence falls on the next content word that is close to the end of the thought group (i.e., defined, impact). Afterwards, pollution is largely represented by the pronoun it, and never receives prominence again. The repeated word scientists (thought groups, 7, 8) behaves the same way that pollution does. Finally, the word problem occurs in thought groups 7, 8, 11, 13, 15, and it is phrase final in the last three. But it never receives prominence.

1 Let’s continue our discussion of polLUtion. / 2 YESterday / 3 we deFINED pollution. / 4 ToDAY / 5 we’ll talk about the IMpact of pollution / 6 its far-reaching efFECTS. / 7 Many people think pollution is just a problem for SCIentists / 8 but it’s NOT just a problem for scientists. / 9 It affects EVeryone. / 10 Because it affects human LIVES, / 11 it’s a HEALTH problem. / 12 Because it affects PROperty, / 13 it’s an ecoNOmic problem. / 14 And because it affects our appreciation of NAture, / 15 it’s an aesTHEtic problem.”

When talking about a topic over a period of time, important words (like pollution in the paragraph above) can occur many times. After the first time, they are unlikely to receive prominence again because new words will enter the conversation and present new information. In these cases, prominence occurs on the new words.

Prominence placement on new information is often complicated because repeated words can be repeated as pronouns (e.g., pollution = it), and because old information usually moves earlier in sentences so that new information can occur at the end.

Native speakers of English use prominence to signal new information naturally, but it takes a lot of concentration and thought for L2 speakers to understand how new information works.

Prominence – Marking Contrasting Categories

An important function of prominence is to call attention to contrasts and comparisons. For example, if a native speaker of English heard someone say the following, with prominence on GIRLS, it would call to mind a different category that is related to (and being contrasted with) girls, that is, boys. This use of prominence is called contrastive stress.

- The work was finally finished by the GIRLS in the class. (Interpretation: the boys didn’t help)

Contrastive stress depends on the meaning that a speaker intends to communicate and the categories that they intend to evoke in the listener’s mind. Dwight Bolinger, the famous linguist, wrote that contrastive stress occurs when “two or more items are counterbalanced and preferences indicated for some group member or members. It [contrastive stress] is the most conspicuous of all the occurrences of phonetic highlighting by reason of its frequency and the extra oomph that we put into it, and because our attention is focused in a way that makes us aware of our speech and not just of our meaning” (1961, p. 83).

Sometimes speakers make the contrasts explicit, and sometimes they don’t, as in the examples below (from Muller Levis & Levis, 2020, p. 318).

Explicit: It’s easier to walk DOWN the stairs than UP the stairs.

Implicit: I can’t believe I fell UP the stairs this time. (implicit contrast to DOWN)

In general, contrastive stress is present when explicit comparisons are being called to mind as in alternative questions) or when non-final prominence occurs for no clear reason other than calling attention to some type of category.

Alternative questions:

Which would you rather have, CAKE or COOKies?

Should we go to New YORK or BOSton?

Non-final prominence:

CaliFORnia sounds really good to me.

Implicit meaning: I think California, not somewhere else, is best.

Teaching prominence for contrasts does not necessarily require reading aloud because learners can often understand the reasons for using prominence through the use of visuals. Levis and Grant (2003, p. 18) suggested using Venn diagrams or charts to promote the use of contrastive stress, as shown below.

| Feature | Automobile A | Automobile B |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 3 years old | 6 years old |

| Cost | $8,500 | $6,500 |

| Size (seats) | 4 passengers | 5 passengers |

| Size (trunk) | large trunk | small trunk |

| Make | American-made | German-made |

| Gas mileage | 25 miles per gallon/highway | 35 miles per gallon/highway |

| Reliability | very reliable | not very reliable |

Levis and Muller Levis (2018) suggest using pictures that promote the use of contrasts, along with teaching lexical frames to make using contrastive stress easier. In the next example, learners can compare the two pictures which have only one obvious contrast.

Repeated Questions and Shifting Prominence

Another use of prominence involves repeated questions, an interactive pattern that occurs with many kinds of formulaic questions. In the common greeting routine below, the same question is asked by Person 1 and Person 2, but the placement of prominence changes when Person 2 asks the question. Because the content of the pronoun “you” has changed when Person 2 asks the question, Person 2 uses prominence to call attention to the change. (If prominence stays the same, it creates confusion about whether Person 2 was actually listening to Person 1.)

- Person 1: How ARE you? Person 2: Great! How are YOU?

These kinds of repeated questions occur frequently, and they involve many different formulaic questions (e.g., “Where are you from?”, “What are you doing?”, etc.). Like contrastive stress, these types of prominence changes can be taught without understanding other types of prominence placement.

8.4 Prominence on Function Words

Prominence almost always falls on content words (i.e., nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs). It rarely occurs on function words (such as articles, auxiliary verbs, prepositions, and the verb BE), but there are times that it does: in contrasts and in utterances that have no content words, such as Where are you from? or It wasn’t on. In other words, thought groups have to have a prominent syllable, even if it’s on a function word.

Where do you expect the prominence in these sentences? Identify the word that you think will receive prominence in each phrase, then listen to check your answers.

Where was it from?

They’re not around.

Was it off?

You aren’t on it?

Another common use of prominence on function words is to mark contrasts, as in the example from Levis and Muller Levis (2018). If a speaker is trying to compare the two pictures of the black cat, they will naturally place prominence on the prepositions (i.e., the cat in the first picture is ON the table, but in the second picture, the cat is UNDER the table). Other examples of function word contrasts would be in sentences like “I didn’t say YOU should do it, I said SHE should do it.”

Other Exceptions to Default Prominence Placement

Cruttenden (1990) includes three other types of sentence types that are exceptional in prominence placement: event sentences, sentences with final adverbials, and adjective WH-objects. These types of sentences don’t occur often, but when they do, they are noticed by teachers and learners who hear that prominence placement doesn’t follow the rules that are otherwise very reliable.

Event Sentences (an expected verb does not get prominence)

AMAZON just showed up. (Explanation: The regular delivery truck was expected)

Your MOTHER called. (Explanation: This is what your mother usually does.)

Final Adverbials (some final adverbials just set a context or a comment but are not important)

I’ll MEET you there. (Adverbial there doesn’t add any important information)

I can’t DO it, unfortunately (The final adverbial is not very informative)

Adjective Wh-objects (The Wh-object is moved to the front of the question)

What BOOKS did you buy? (Based on knowing they bought some books)

Which CLASSES are you taking? (Based on knowing they are taking some classes)

8.5 Technology Corner

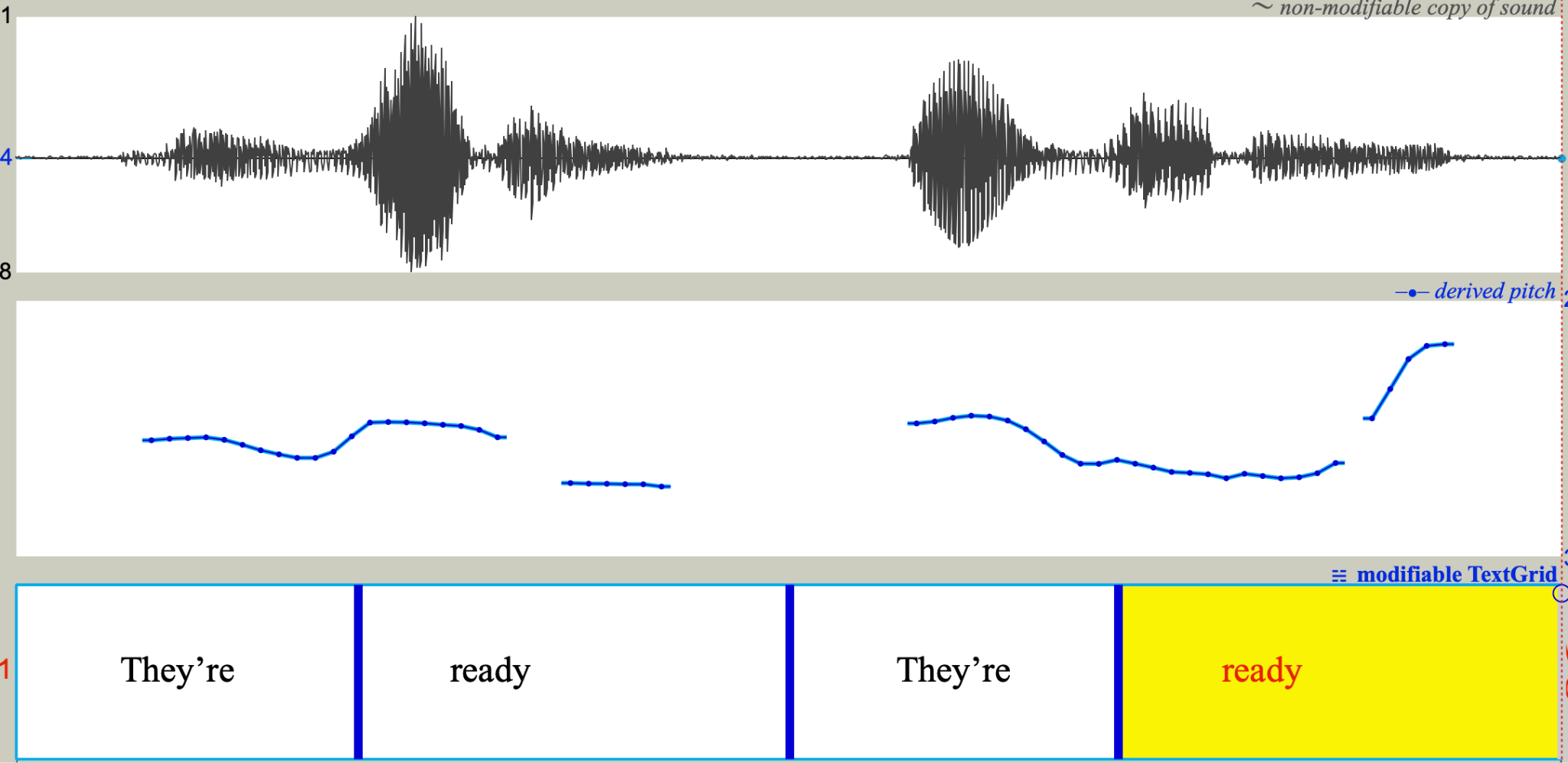

To illustrate prominence, both when the pitch goes up and when it goes down, it is helpful to use Praat with the pitch tracking shown. In the example below, the sentence “They’re ready” is shown both as a statement and as a question. The statement has a jump up in pitch on “ready” (before the pitch falls to the end of the sentence), and the question has a drop in pitch from “They’re” to “ready” before the pitch rises at the end of the sentence.

Kazoos, another type of old-fashioned technology, are also effective in teaching prominence. The use of kazoos can help the learner pay attention to pitch by masking the other aspects of pronunciation. An illustration of the use of kazoos is shown in the video below.

8.6 ProFUNciation – Why Prominence Matters

In a common greeting routine, it’s important to change prominence when returning a question. Otherwise, the other person will think you were not listening to them.

- Person 1: How ARE you?

- Person 2: How ARE you?

- Person 1: ???? (Confused)

English speakers are used to hearing names with final prominence. Otherwise, they don’t hear them. So even though you know how to say your own name, unless you wrap it in a package of English prominence placement, English-speaking listeners will not “hear” you.

Unexpected prominence

- Person 1: My name’s JONAS Garcia.

- Person 2: I’m sorry, could you repeat that, please?

- Person 1: (feels frustrated)

Expected prominence

- Person 1: My name’s Jonas GarCIa.

- Person 2: Nice to meet you. I’m Jason CLARKson.

- Person 1: (can now continue the conversation)

8.7 Activities

Description and Analysis

Exercise 8-1. Four Explanations

Directions: The teacher can choose one or more of the explanations for what prominence is and how it is used in communication in English.

In English phrases and sentences, at least one word is always emphasized or prominent. In the examples, the prominent word is the last one in each sentence.

My name’s Angela SMITH

But most people call me ANGIE

I’m originally from CHICAGO

Prominence involves several features in English. Most importantly, the emphasized word in a sentence has a change in pitch that makes it different from the words before it. The pitch change occurs on the stressed syllable of the emphasized word. After the pitch change, the voice then returns to its normal level.

My name’s Angela SMITH

But most people call me ANGIE

I’m originally from CHICAGO

Explanation 2

Prominence gives a particular melodic shape to English speech. Listeners expect this shape, so using the expected shape makes it easier to understand speech.

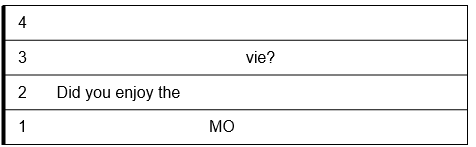

Prominence usually falls on the last word, but only if the last word is a CONTENT WORD, that is, a NOUN, VERB, ADJECTIVE, or ADVERB. Other types of words (like prepositions or pronouns) are not usually prominent in speech. In the two sentences below, the first ends in a CONTENT WORD (SISTER), but the second ends in a pronoun, so the prominence would go on the last CONTENT WORD (MONEY).

Compare:

- I gave the money to your SISTER.

- I gave the MONEY to her.

Explanation 3: Identifying Content Words

It’s important to be able to identify CONTENT WORDS in speech. They are the most common place for prominence.

Underline the CONTENT WORDS in the sentences.

In introductions / the family name receives prominence.

If you use only your first name / then emphasize it.

Answers

In introductions / the family name receives prominence.

If you use only your first name / then emphasize it.

When the last word in a spoken sentence is not a CONTENT WORD, as in “I gave the money to her”, it is especially important to drop the voice pitch after the prominent syllable. This makes it easy for listeners to pay attention to only one prominent syllable at the end.

Explanation 4: Visualizing Prominence

One way of visualizing prominence is to use a kind of musical staff with different pitch levels from 1 (low) to 4 (high).

Does prominence always have an increase in pitch?

In questions that end in a rising pitch, the prominent syllable usually drops in pitch. This makes it easier to notice the final rise in pitch.

Listening Discrimination

Exercise 8-2. Identifying Prominence.

Directions: Play the recording and have learners identify the word that receives prominence. Go over the answers and play the recordings again to help hear prominence more clearly.\

She couldn’t have done that.

There was some damage on it.

Did you remember to call her?

What time is it?

I don’t know where he is.

The car is still outside.

Exercise 8-3. Identifying Prominence in Small Talk

Directions: Listen and identify the prominence placement in the small-talk questions. Then practice shadowing the question with the same prominence pattern.

What’s your name?

Where did you grow up?

What are you studying?

Where do you work?

How do you like (your city or state) ?

Where do you want to travel?

What’s your favorite sport?

Exercise 8-4. Identifying Prominent Syllables.

Directions: Listen to each name of a famous person or place and identify the prominent syllable in each.

Tracy Chapman

Taylor Swift

Brad Paisley

Johnny Depp

Paul McCartney

Jennifer Lopez

Chicago, Illinois

Los Angeles

London, England

Beijing, China

Seoul, Korea

Sydney, Australia

Exercise 8-5. Prominence in a TEDTalk.

Directions: Listen from John O’Donnell’s TEDTalk, starting at 7:28. Identify the prominent word in the following sentences from the talk

- We are now at a very interesting point.

- Technology like this is simple.

- It’s boring.

- It can go to scale fast.

Exercise 8-6. Predicting Prominence in a speech.

In the following speech, the first 10 spoken sentences are transcribed. Identify the last CONTENT WORD in each spoken sentence. Then listen and decide if it is pronounced with prominence. What does this tell you about normal, default prominence placement?

- I get a deep sense of HOPE

- when I look at this BRICK.

- It’s going to spend the next 50 years of its life cutting CO2,

- and bricks LIKE it

- are going to CUT

- 15 PERCENT

- of world CO2.

- So let’s TALK about that,

- but FIRST,

- we have to talk about FIRE.

Controlled Production

Exercise 8-7. Prominence on Names (adapted from Wayne Dickerson)

Directions: Communication works best when speakers put prominence on the words that listeners expect to be prominent. For names, this means prominence on the stressed syllable of the last part of the name. If the name has one part, it will be prominent If the name has two or more parts, it will still have prominence on the last part of the name.

| Example 1

Example 2 |

HonoLUlu

PAris |

Honolulu, HaWAIʻi

Paris, FRANCE |

|---|

Match the city with its state. Place prominence on the last part of the name.

Exercise 8-8. Shifting Prominence on Names.

Directions: Person 1 says a city from the list. Person 2 says the city and the state. Example:

- Person 1: DENver

- Person 2: Denver, ColoRAdo

Exercise 8-9. Learning World Cities and Countries

Directions: Find out how people say the name of the capital of your country and the name of your country. How is this different from what you would say to pronounce it?

Exercise 8-10. Saying Personal Names

Directions: Say these names with prominence on the last part of the name. Change the prominence in each row to keep prominence at the end.

General Rule. Personal Names are said the same way that names of cities, states, and countries are. Practice saying names with final word prominence.

| First Name | First and Last Name | Title, (First and) Last Name |

| JOshua | Joshua GREEN | Dr. Joshua GREEN |

| EMily | Emily JOHNson | Ms. JOHNson |

| First Name | First and Last Name | Title, (First and) Last Name |

| Robbie | Robert Martin | Mr. Martin |

| Suzanne | Suzanne Anderson | Mrs. Suzanne Anderson |

| William | Bill Johnson | Professor Johnson |

| Gabriel | Gabe Martinez | Dr. Bergstrom |

| Benjamin | Ben Anderson | President Anderson |

Exercise 8-11. Prominence Dialogue Reading

Directions: Listen to the dialogues. Then in pairs, read the dialogues. Place prominence on the final content word in each sentence.

A Gift (Dialogue 1)

Chen: Bill, could you give me some advice?

Chris: I’d be glad to. What do you need?

Chen: I’m invited to dinner at Professor Wilson’s house. What should I take?

Chris: Flowers are always a good idea. But not too expensive.

Chen: That sounds good. What’s a good price to pay?

Chris: Not more than 20 dollars.

Chen: Where can I get them?

Chris: Probably the grocery store is best. Get them wrapped in paper.

Chen: Thanks. I’ll get them right before I go.

The Gift – Next day (Dialogue 2)

Chris: So how was the dinner?

Chen: It was nice. The flowers were a good gift. Professor Wilson liked them.

Chris: What did you eat?

Chen: Some kind of soup. I forget what it was called. And bread and cheese.

Chris: You sound surprised.

Chen: In my country, soup is always just the beginning. Here it was the main course.

Chris: Hopefully you didn’t end up hungry.

Chen: No, I was just confused. But the dessert was great.

Exercise 8-12. Prominence on Choices

Directions: In pairs, listen to, then read the dialogue between the man in the bar and the bartender. Pay attention to how prominence falls on choices in the questions asked by the bartender.

Sometimes, prominence has a special placement on more than one word. One situation this happens is when asking choice questions, as in this dialogue adapted from a comic strip. In each choice question, the bartender would place prominence on both choices.

Man in bar

I’ll take a beer.Alcohol, of course.

Domestic

I guess Dark.

Whatever happened to stopping in for a quick one?

Bartender

ALcohol or NON-alcohol?

IMPORTED or DOMESTIC?

LIGHT or DARK?

BOTTLE or DRAFT?

Exercise 8-13. Prominence on new information

Directions: In pairs, listen to and then read the dialogue between the two roommates. Make sure the prominence is placed on the new information. Follow these Instructions to prepare for the dialogue.

- Identify the last content word in each sentence.

- Identify if the last content word has already been mentioned.

- If yes, then find the last new word that has not been mentioned.

- Mark prominence on that word.

- Read the dialogue with another student.

Midterm Anxiety (Two roommates)

Roommate 1: Shoot! I’ve really got to study. Where’d I put my book?

Roommate 2: Which book?

Roommate 1: My calculus book.

Roommate 2: Maybe you put it on the bookshelf.

Roommate 1: I never put it on the bookshelf!

Roommate 2: You could look in your bedroom.

Roommate 1: I’ve already looked in the bedroom. This place is a mess. I can’t find anything around here.

Roommate 2: Hey, wait a second. You have the book in your hand.

Exercise 8-14. Jazz Chant

Jazz Chants were created by Carolyn Graham in the 1970s. They are good practice activities for grammar, fluency, and pronunciation. This Jazz Chant has a set of double prominences, one early in the phrase and the other late. This helps to practice prominence placement.

Directions: Read the Jazz Chant aloud with prominence placed at the end of each sentence.

A Bad Day (Carolyn Graham, Jazz Chants, 1978)

I overslept and missed my train,

Slipped on the sidewalk

In the pouring rain,

Sprained my ankle,

Skinned my knees,

Broke my glasses,

Lost my keys,

Got stuck in the elevator,

It wouldn’t go.

Kicked it twice

and stubbed my toe,

Bought a pen

that didn’t write,

Took it back

and had a fight,

Went home angry,

Locked the door,

Crawled into bed,

Couldn’t take any more..

Guided & Communicative Production

Exercise 8-15. Self-Introductions

Directions: Introduce yourself to someone else. Place prominence on the last part of each name. Use the dialogue frame below or modify it to make your own dialogue.

-

- Hi, I’m _______________________.

- Hi, it’s nice to meet you.

I’m _____________________.

Where are you from? - I’m from _____________________.

- Cool. I’m from __________________. It’s in _____________.

Exercise 8-16. Small Talk and Repeated Questions

Background information – Conversation often includes small talk with questions that are appropriate with someone you don’t know well. In English, this is a common question.

John: Hi, Chris. How are you DOING?

Chris: Hi John. I’m fine.

How are YOU doing?

Directions: Discuss which of the following questions are appropriate to ask other people, especially strangers. Which of these questions are appropriate in English? In your culture?

How much do you weigh?

What do you like to do?

How much money do you make?

What do you like to do?

What do you think of this weather?

What do you think of this weather?

How much did that cost?

Where is a good place to shop?

Where is a good place to shop?

What sports do you like?

What is your religion?

Where are you from?

How old are you?

Where are you from?

What’s your favorite food?

Exercise 8-17. Repeated Questions

Directions: Read the self-introduction dialogue and pay attention to prominence in the repeated question, Where are you from? Introduce yourself to someone else using the dialogue as a frame, but use your own information.

Person 1: Hi, my name’s John. John Lewis.

Person 2: Hi, I’m Zoë Reed

Where are you FROM?

Person 1: I’m from Iowa. A town called Ames.

Where are YOU from?

Person 2: I’m from Boston.

Exercise 8-18. Comparing two pictures (Levis & Muller Levis, 2018)

Directions: Use contrastive prominence to compare the two house pictures. For example, if you were comparing two pictures of a cat, you would say:

“In the FIRST picture, the cat is ON the table, but in the SECOND, the cat is UNDER the table.”

To express contrasts, it may help to use some of the following language.

- The first house is ________, but the second house is __________.

- The house in the first picture has _________, but the house in the second picture has __________.

- One house is _________________, but the other house is __________________.

- This house _________________. That house _______________.

- The house on the left ________________. The house on the right _______________.

Exercise 8-19. Making an announcement.

Directions: Imagine that you are the spokesperson for a student organization on campus and that you are meeting those interested in the club for the first time. Study the information for about a minute. Then, talk to the people interested in your organization by giving them important information about the organization.

Group: Amnesty International

When: Wednesdays, 7-8:30

Place: 104 Frank Thompson Building

Special Sessions: Research on Current Issues (specific issues announced each Wednesday)

Mondays, 3-5 Natural Resources Library

Rallies: Monday, April 1

Guest Speaker: Dr. John Layaman, Director of Washington D.C. Chapter. To be

held outside the Student Center at 12:00. Bring a lunch

Wednesday, April 17

Staff Awareness Day- Activities from 12:00-2:00

Final Words

“Get involved so that all people and groups will enjoy the freedom and rights they deserve!”

Exercise 8-20. Correcting Wrong Information.

Speaking to a group (Corrected version)

Directions: Imagine that you are the spokesperson for a student organization on campus and that you are meeting for the second time. There have been unforeseen changes about when the club will meet. Give the information by correcting the mistaken information.

Group: Amnesty International

When: Every other Wednesday (not every Wednesday)

8-9:30 p.m. (not 7-8:30)

Place: 204 Frank Thompson Building (not 104)

Special Sessions: Research on Current Issues (specific issues announced each Wednesday)

Mondays, 3-5 Natural Resources Library

First Monday of the month, 3:30-5:30

Rallies: Monday, April 1 (Tuesday, April 2)

Guest Speaker: Dr. John Layaman, Director of Washington D.C. Chapter. To be

held outside the Student Center at 12:00. Bring a lunch

Wednesday, April 17

Staff Awareness Day- Activities from 12:00- 1:00 (not 2:00)

Final Words

“Remember, we need your involvement!”

8.8 References

Bolinger, D. (1961). Contrastive accent and contrastive stress. Language, 37, 83-96. https://doi.org/10.2307/411252

Crystal, D. (1969). Prosodic systems and intonation in English. Cambridge University Press.

Dickerson, W. B. (1989). Stress in the speech stream: The rhythm of spoken English. University of Illinois Press.

Graham, C. (1978). Jazz chants: Rhythms of American English for students of English as a second language. Oxford University Press.

Grant, L. (2012). Well said, 3rd ed. Cengage.

Hahn, L. D. (2004). Primary stress and intelligibility: Research to motivate the teaching of suprasegmentals. TESOL Quarterly, 38(2), 201-223. https://doi.org/10.2307/3588378

Halliday, M. (1967). Intonation and grammar in British English. The Hague: Mouton. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783111357447

Jenkins, J. (2000). The phonology of English as an international language. Oxford University Press.

Kenworthy, J. (1987). Teaching English pronunciation. Longmans.

Ladd, D. R. (1996). Intonational Phonology (Vol. 79). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511808814

Levis, J. M., & Grant, L. (2003). Integrating pronunciation into ESL/EFL classrooms. TESOL Journal, 12(2), 13-19. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1949-3533.2003.tb00125.x

Levis, J., & Muller Levis, G. (2018). Teaching high-value pronunciation features: Contrastive stress for intermediate learners. CATESOL Journal, 30(1), 139-160. https://doi.org/10.1075/jslp.23049.lev

Muller Levis, G., & Levis, J. M. (2020). Teaching contrastive stress for varied speaking levels. In O. Kang, S. Staples, K. Yaw, & K. Hirschi (Eds.), Proceedings of the 11th Pronunciation in Second Language Learning and Teaching conference, ISSN 2380-9566, Northern Arizona University, September 2019 (pp. 316–325). Ames, IA: Iowa State University.