Overview of the National Poultry Improvement Plan (NPIP)

What is the NPIP?

NPIP is a cooperative industry, state, and federal program that serves to safeguard, certify, and represent the health of US poultry (Figure 1). NPIP health status classifications are the officially recognized standard by which US poultry and egg industry participants demonstrate freedom from domestic and trade impacting diseases (Figure 2).

- Figure 1. National Poultry Improvement Plan (NPIP) logo

- Figure 2. Sampling of NPIP health status classification shields

The NPIP is an active and continuously evolving program implemented across all segments of the US poultry and egg industries.[1][2][3][4][5][6] The NPIP is coordinated by USDA APHIS Veterinary Services. It is informed and driven to meet the needs of the industries served, updated every two years by a formal congress of US poultry and egg industry stakeholders, administered by NPIP Official State Agencies, and implemented by NPIP program participants. NPIP approves diagnostic test methods, determines requirements for specified NPIP health status classifications, and certifies laboratories.

NPIP participants utilize the program to certify the health status of poultry flocks, slaughter plants (i.e., supply chains), products (i.e., eggs and chicks), and states in accordance to the definitions and standards set forth in the NPIP. NPIP health status classifications are commonly referenced, used, or required at points of sale, exhibition, interstate movement, and in support of international trade. Participation in the NPIP is voluntary and almost universal among commercial operations across the US. Participant names and NPIP classifications held are listed on the NPIP website (www. poultryimprovement.org, see the NPIP Participants by State/Territory and the H5/H7 Avian Influenza Monitored Program tabs).

Why does NPIP work?

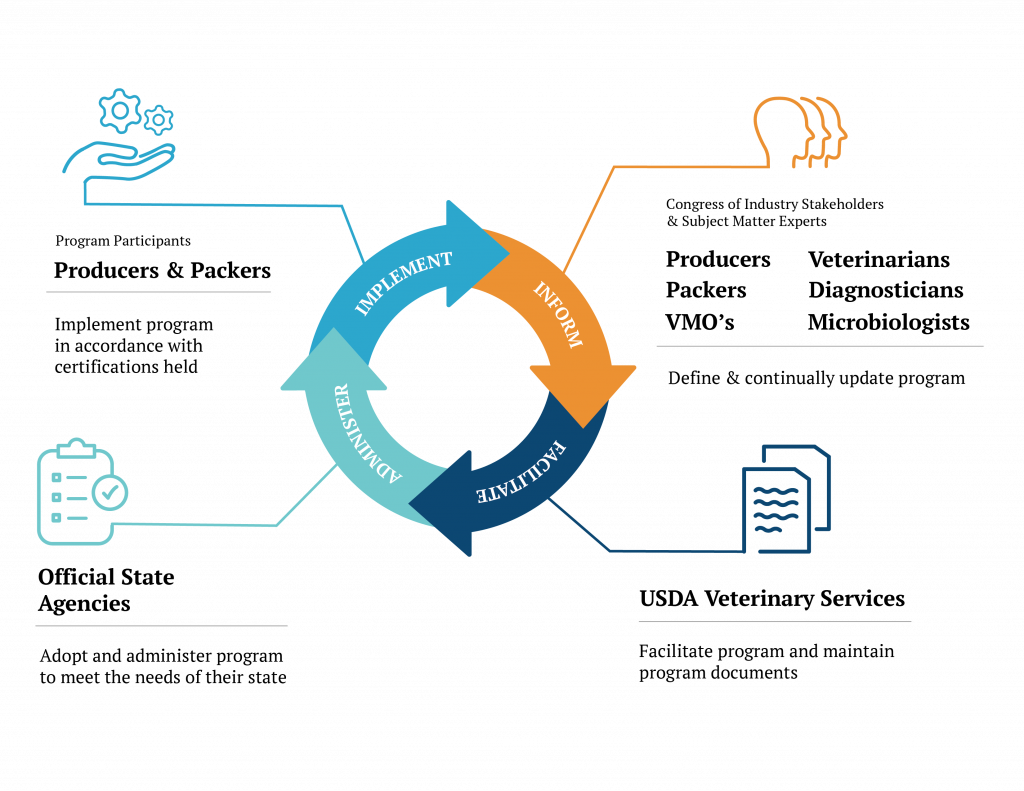

Figure 3, entitled Partnering to Safeguard and Better Animal Health, is our best effort to most succinctly describe NPIP’s ongoing system of operations across the US poultry and egg industries. A formal congress of industry stakeholders and subject matter experts define and continually update the program. USDA APHIS Veterinary Services coordinates the program and maintains program documents.

NPIP Official State Agencies adopt and administer the program to meet the needs of the industries in their state. Program participants (i.e., producers and slaughter facilities) implement the program in accordance with certifications held. The circular nature of the relationships between the congress of industry stakeholders and subject matter experts, USDA Veterinary Services, NPIP Official State Agencies, and program participants provides for the continuous improvement and updating of the program over the course of time.

In these authors’ opinion, this broadly inclusive and forward-looking operational structure has been a critical element to NPIP’s success, relevance, and ability to meet the changing needs of the US poultry and egg industries. NPIP’s operating structure enables the breadth and depth of species and industry specific know-how that exists across the full-spectrum of industry participants (e.g., producers, slaughter facilities, veterinarians, diagnosticians, microbiologists, and epidemiologists) to be utilized in deriving practical standards, definitions, and policies that serve to better poultry health and competitiveness of the US poultry and egg industries.

Participation in the NPIP has grown over time to now being almost universal among commercial operations. This critical mass of participation is unquestionably another essential element of NPIP’s long-standing impact on bettering the health of US poultry and associated industries. NPIP’s tripartite partnership (industry, state, and federal) and democratic approach used in the decision making process has a well-established record for delivering workable animal health assurance solutions for the US poultry and egg industries. Much of the burden and responsibility for bringing forth, debating, and directly addressing species- and industry-specific animal health issues of industry-wide significance are deferred from the federal and state veterinary medical officials and associated agencies working in isolation, to NPIP’s formal congress of industry stakeholders and subject matter experts. This approach lends itself towards a sense of shared ownership in NPIP’s officially recognized standards, definitions, policies, and health status classifications recognized across participants, participating states, USDA, and international trading partners.

NPIP’s origins, focus, and evolution

During the early 1900s, bacillary white diarrhea, caused by Salmonella enterica subspecies enterica serotype Pullorum (Salmonella Pullorum–also known as Pullorum Disease), killed 80% or more of the chicks in affected flocks in the United States. In 1913, a test was developed that identified infected birds so they could be eliminated from the flock. Individuals in the poultry industry soon recognized that the most effective way to control Pullorum Disease would be through a coordinated, nationwide effort. This effort led to the development of the NPIP which officially began in 1935.

The NPIP initially focused on testing for Pullorum Disease and improvement of breed-based genetics. Testing for Pullorum Disease and a similar disease, Fowl Typhoid (Salmonella Gallinarum), followed by removal of reactors, has been a very successful ongoing segment of the NPIP. Both diseases have been eliminated from the US commercial poultry industry, but this testing remains a cornerstone of the NPIP.[7]

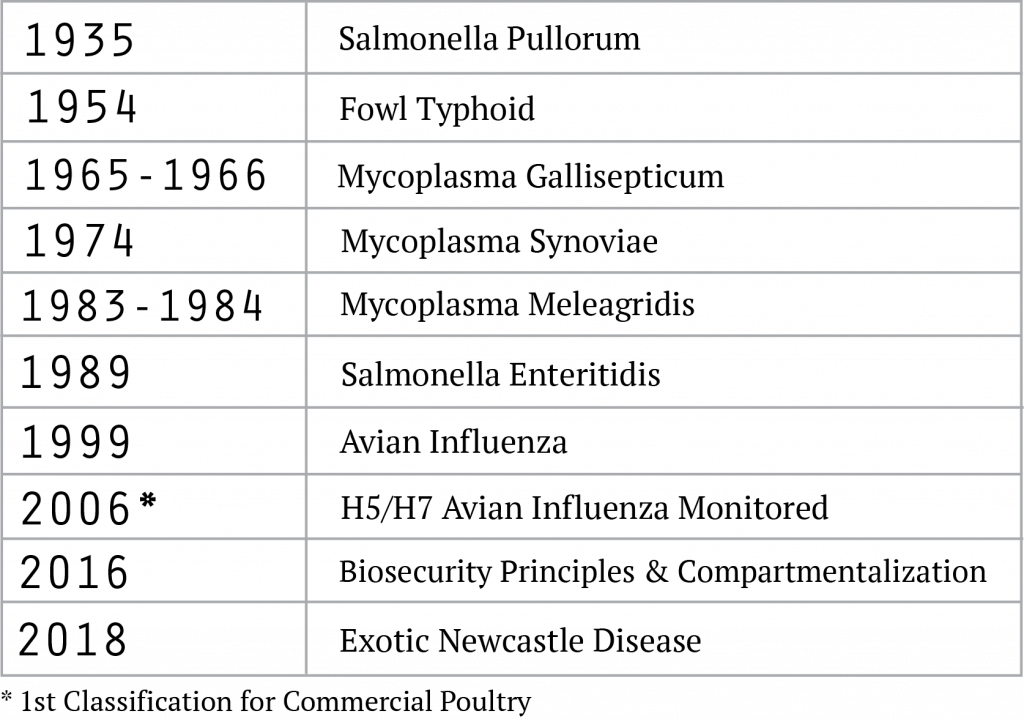

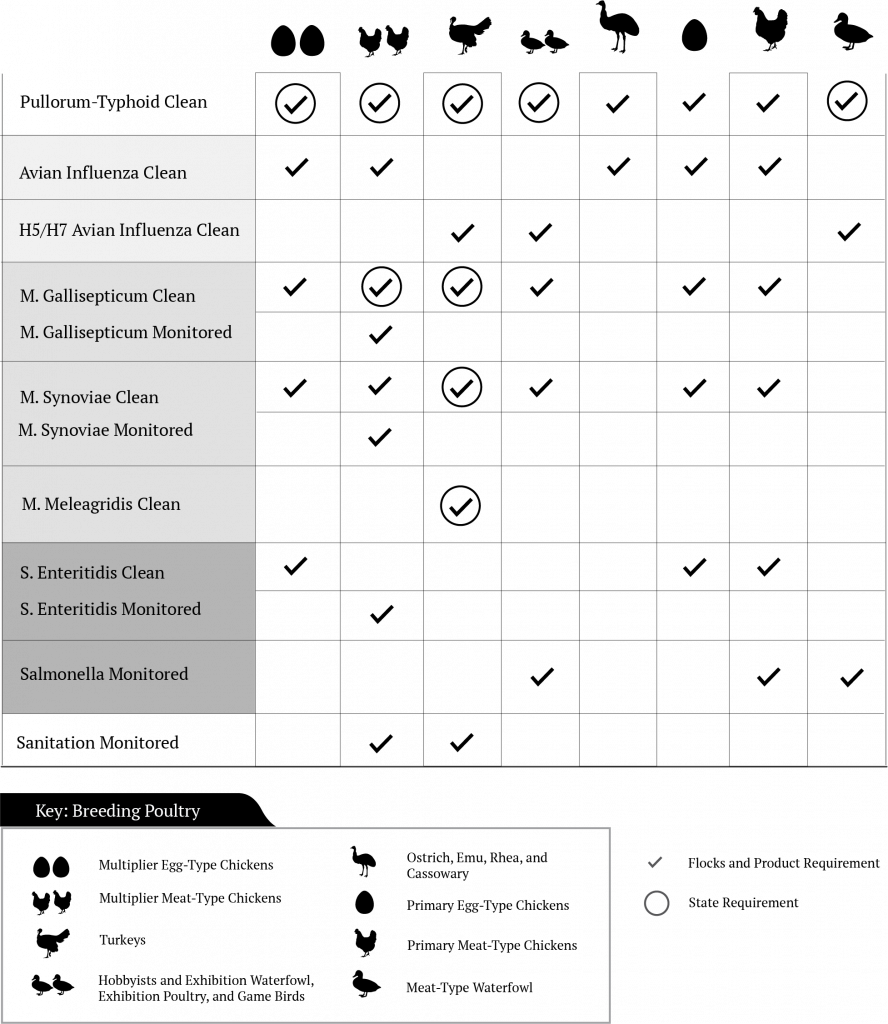

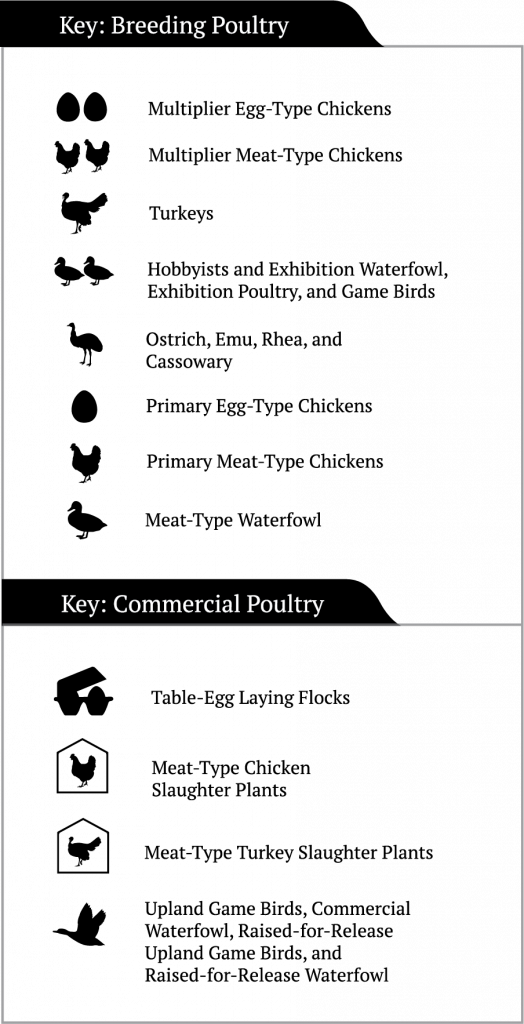

NPIP’s primary focus, dating back to its origins, centers on certifying Breeding Poultry as free of specified vertically transmitted diseases of high consequence. The number of diseases within NPIP’s scope, and associated health status classifications for Breeding Poultry, has expanded over time (Figure 4).[8] The current NPIP classifications for the various types of Breeding Poultry are shown in Figure 5.[9] These pathogen-specific NPIP health status classifications are broadly recognized and represent the foundation by which the health status of Breeding Poultry and their offspring are characterized at points of sale, exhibition, and for interstate and/or international commerce.

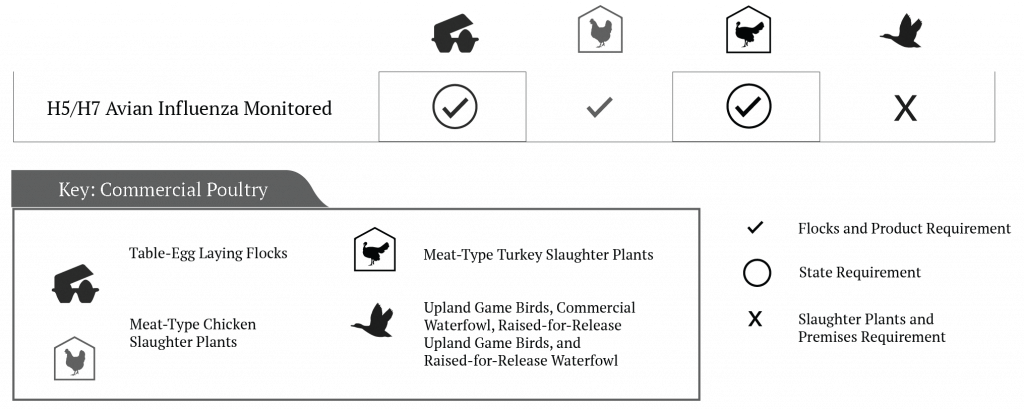

While NPIP’s history and mission are deeply rooted in the control and elimination of vertically transmitted diseases in Breeding Poultry, NPIP’s scope expanded significantly in 2006 to include an “H5/H7 Avian Influenza Monitored” classification. This classification was the first (and still the only) NPIP classification for Commercial Poultry (Figure 6).[10] A disruptive outbreak of a lowly pathogenic H7N2 Avian Influenza Virus (AIV) in the Shenandoah Valley and North Carolina in 2002, a more isolated outbreak of a highly pathogenic H5N2 AIV (HP-AIV) in Texas in 2004, coupled with increasing AIV-related concerns around the world, and the growing importance and value of export markets to the US poultry and egg industries, each contributed to this substantive change in NPIP’s scope.

Because HP-AIV is considered a foreign animal disease, response plans are outside the scope of the NPIP. Nevertheless, the H5/H7 Avian Influenza Monitored classification provides participating Commercial Poultry operations, in states and regions not affected by an AIV event of significance (i.e., HP-AIV or a lowly pathogenic AIV), an officially recognized mechanism for demonstrating freedom from disease. Thus, the H5/H7 Avian Influenza Monitored classification held by meat-type chicken and turkey slaughter plants, commercial table egg laying operations, and states have played a primary role in helping sustain export markets and interstate commerce from unaffected regions during times of an AIV outbreak of significance affecting Commercial Poultry in the US.

NPIP has an active, organized, scientific, thorough, and democratic process for vetting proposed modifications and updating the NPIP. Recent updates of significance (Figure 4) include the requirement that commercial operations have a biosecurity plan in place (2016), and more recently, Virulent Newcastle Disease (vND) was introduced into NPIP program language (2018).[11] The first update was prompted by lessons learned from the 2015 HP-AIV outbreaks centered in the upper Midwest, and the latter by concerns over the recent vND outbreaks in California and to broaden the scope of NPIP’s compartmentalization efforts.

Consistent with the guidelines set forth by the OIE (World Organization for Animal Health), NPIP has also recently been providing leadership towards developing a pathway for poultry operations to become officially recognized “compartments”. Through this effort, a primary breeder operation (Aviagen®) became the first commercial livestock or poultry operation in the US to become an officially recognized compartment (2018). This status positions operations to export their offspring or products during a time of animal health crisis in the US or within their state. Other US primary breeder operations that distribute poultry genetics domestically and abroad are further exploring the opportunity to become officially recognized compartments to support the future of their operations. Commercial Poultry are not presently pursuing compartmentalization consistent with OIE guidelines due to the costs, complexities, and feasibility of achieving this high standard. A more complete description of OIE compartmentalization guidelines are available in the OIE’s Terrestrial Animal Health Code Chapter 4.4 (Application for compartmentalization) on OIE’s website (oie.int). NPIP’s management guidelines and protocols for Avian Influenza compartmentalization for Primary Poultry Breeding Companies may also be another compartmentalization reference of interest (see NPIP Program Standards – Subpart F, available on NPIP website, poultryimprovement.org).

It should be recognized that compartmentalization, which provides a mechanism to demonstrate freedom of disease from specific sites or operations within affected regions, is distinct from, and far more difficult than, regionalization. Regionalization involves demonstrating evidence of freedom of disease in unaffected, or no longer affected, areas, or regions. The US and other trading partners have a history and precedent for respecting and honoring regions within an affected country as free of specified diseases. Disease control efforts within the US, and throughout the world, have long designated health status by region (counties, states, or provinces) over the course of large-scale disease control or eradication efforts.

NPIP administration and implementation

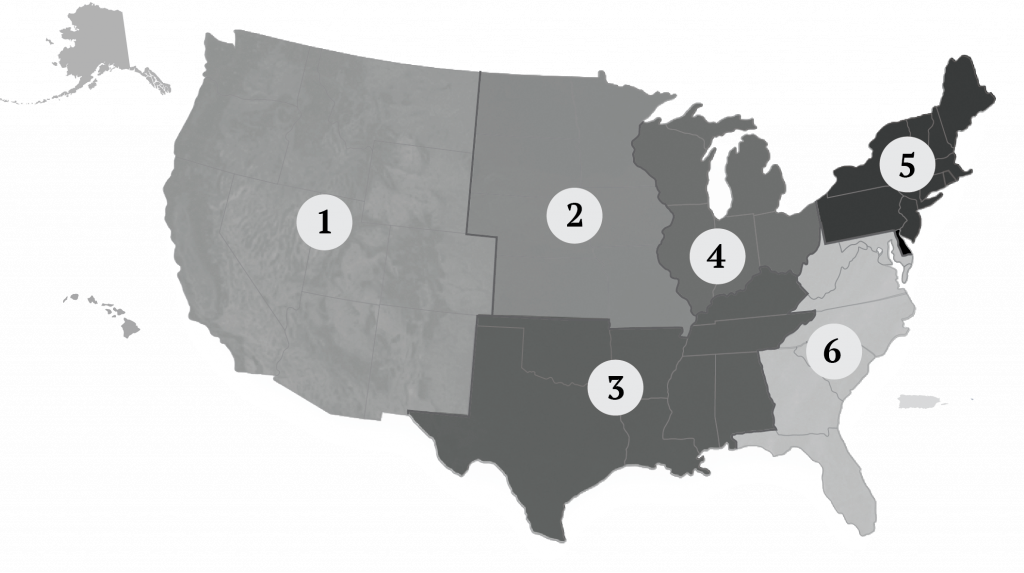

National administration

The NPIP national headquarters and its five USDA APHIS employees are located in Conyers, Georgia. Locating and operating NPIP’s small national administrative office in a poultry centric region of the country is an issue of importance to US poultry and egg industry stakeholders. Many international visitors and trading partners visit Georgia (e.g., NPIP national headquarters, Georgia Poultry Lab Network, Poultry Diagnostic and Research Center at the University of Georgia, USDA Southeast Poultry Research Laboratory, and a myriad of commercial poultry operations) to learn and better appreciate the poultry health control programs and poultry and egg industries in the US. The NPIP Senior Coordinator (the senior NPIP administrator) provides leadership for NPIP activities at the national level. The NPIP General Conference Committee consists of elected individuals (one at-large member and six regional representatives) who provide oversight and industry representation in the NPIP administration (Figure 7).

General Conference Committee members are volunteers elected to 4-year terms at the NPIP Biennial Conference and serve as the official advisory committee to the US Secretary of Agriculture on matters pertaining to poultry health. The NPIP Senior Coordinator reports directly to the USDA APHIS Director of Avian, Swine, and Aquatic Health Programs. The national NPIP office provides support to, and coordination among, the NPIP Official State Agencies.

The NPIP Technical Advisory Committee consists of a diverse group of subject matter experts from across the US that play a substantive role in vetting, and in some cases, crafting proposed updates to the NPIP. The Technical Advisory Committee consists of veterinarians, diagnosticians, microbiologists, and epidemiologists and has working groups within it often focused on specific pathogens, health status classifications, or particular areas of the NPIP.

State administration

The NPIP Official State Agency is the state authority recognized by the USDA to cooperate in the administration of the NPIP. Determination for participation in the NPIP is on a state-by-state basis. Currently, all 50 states and one US Territory (Puerto Rico) have a memoranda of understanding with USDA APHIS and participate in the NPIP. Each NPIP Official State Agency must implement the NPIP as stated in the Code of Federal Regulations (9 CFR) and NPIP Program Standards document. However, participating states can adopt and follow additional state-specific poultry health-related requirements that extend beyond the NPIP associated claims, requirements, and standards, in accordance with their state’s animal health administrative rules. States commonly reference, adopt, or defer to the definitions and standards set forth by NPIP.

While NPIP is nationwide in scope, each NPIP Official State Agency operates and administers the program in a manner that best meets the needs and interests of their state’s poultry and egg industries. This includes working with their respective poultry and egg industry association(s), state animal health officials, and state department of agriculture, to determine an operating and personnel reporting structure that works best for their state. NPIP Official State Agencies are typically housed within the state animal health official’s office, state department of agriculture, state poultry and egg industry association, or state-affiliated veterinary diagnostic laboratory. The “heavy lifting” involved in executing the NPIP is done by the NPIP Official State Agencies and NPIP participants. The NPIP Official State Agency maintains a list of active NPIP participants and database of all participants’ site-specific information, verifies participants are meeting the specified requirements of the classifications held or being applied for, and maintains an up-to-date list of the NPIP classifications held by each participant in their respective state.

NPIP definitions, standards, and documents

NPIP program definitions and affiliated documents are housed and detailed in Title 9 of the US Code of Federal Regulations (9 CFR) Parts 56, 145, 146, and 147 and the NPIP Program Standards document. The NPIP maintains links to these documents on its website (www.poultryimprovement.org).[12] NPIP program requirements to achieve each of the specific NPIP health status classifications are given in the 9 CFR for Breeding Poultry (Part 145) and Commercial Poultry (Part 146), respectively. The details of the NPIP-approved test methods and NPIP-related sanitary standards have historically been maintained in the 9 CFR (Part 147, subparts A – Blood testing procedures, B – Bacterial examination, C – Sanitary procedures, and D – Molecular examination procedures). More recently, the NPIP Program Standards document was created as a stand-alone document outside of the 9 CFR in an effort to streamline the process of keeping provisions current with the best technologies and practices available.

How is the NPIP updated?

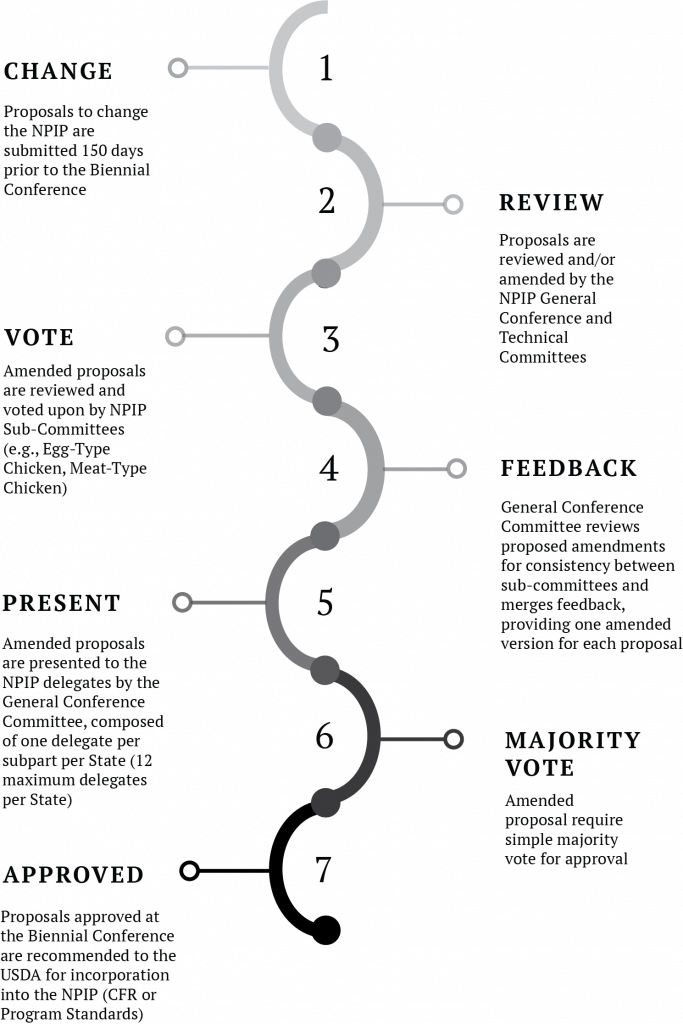

Proposed updates to the NPIP are reviewed and brought forward to a vote by a congress of US poultry and egg industry stakeholders at the NPIP Biennial Conference. Proposed changes must be submitted to the NPIP National Administrative Office at least 150 days prior to the NPIP Biennial Conference. Proposals are shared and reviewed by the NPIP Administrative Staff, NPIP Official State Agencies, NPIP General Conference Committee, and the appropriate subject matter experts in the NPIP Technical Advisory Committee prior to the Biennial Conference. NPIP Official State Agencies commonly host stakeholder meetings seeking input on proposed updates of significance within their state prior to the NPIP Conference. Similarly, NPIP Official State Agencies commonly formulate and discuss proposed updates to the NPIP among their peers and the NPIP National Administrative Office prior to the Biennial Conference. To provide some context to the amount of updating to the NPIP that occurs, 42 proposed updates to the 9 CFR and Program Standards were considered at the 2018 NPIP Biennial Conference. Thirty-six passed as amended, 6 proposals failed.[13]

The NPIP Biennial Conference functions as a formal, and extraordinarily efficient, legislative body. State delegates representing one or more segments (subparts) of the US poultry and egg industries consider, discuss, amend, and vote upon proposed changes to the NPIP (Figure 8).[14] The NPIP has various subparts that address provisions specific to a given segment of the US poultry and egg industries. A listing of the various subparts for Breeding Poultry (9 CFR, Part 145) and Commercial Poultry (9 CFR, Part 146) are listed in Figure 9. Voting rights are specified for each state and subpart. Delegates can only cast a formal vote on proposals with a direct impact on the specific subpart of the US poultry and egg industries they represent. A pictorial of the NPIP update process has been included for reference (Figure 10). If industry-related issues arise, the NPIP General Conference Committee can approve proposed changes to the NPIP on an interim basis, in accordance with standards set forth in the 9 CFR. However, all such interim changes are brought forth for official review, consideration, and vote at the next NPIP Biennial Conference.

Once proposals are approved at the NPIP Biennial Conference, the NPIP National Administrative Office puts together a work plan to submit to USDA APHIS, which is then posted in the Federal Register. The USDA maintains the right to accept or reject the recommendations from the NPIP Biennial Conference. If a proposal is not accepted, USDA’s reason(s) for rejection is published in the Federal Register, after which the poultry industry can provide comment. In addition, if USDA approval for a proposal is uncertain, the NPIP, state animal health officials, and poultry and egg industry stakeholders, may push forward a corresponding resolution that supports the proposal through various committees at the annual US Animal Health Association (USAHA) meeting. The acceptance rate of proposed updates to the NPIP approved at the NPIP Biennial Conference is extremely high. Rare instances of non-acceptance may include such things as proposed updates that infer USDA financial commitments that exceed the funds available. Such constraints are generally well known and openly discussed throughout the vetting process prior to, and at, the NPIP Biennial Conference.

NPIP funding

Funding for the administration and implementation of the NPIP within each state (e.g., NPIP Official State Agency program administration, as well as NPIP participant compliance and diagnostic testing-related costs) varies significantly among states, but commonly comes from multiple sources (e.g., NPIP participants, USDA APHIS cooperative agreements, state departments of agriculture, and state poultry and egg industry organizations). While NPIP Official State Agencies vary substantially based upon the size and composition of the poultry and egg industries and maturity of the NPIP program in their respective state, states would commonly have 1 to 3 full-time equivalents (personnel time) involved in administering the NPIP their state.

The NPIP national headquarters and its core administrative functions are funded by federal dollars under the Avian Health Programs budget line for USDA APHIS. It costs approximately $500,000 to run the NPIP national administrative office each year. Federal dollars (usually $50,000 to $150,000) provided to NPIP Official State Agencies through cooperative agreements are commonly used to support some level of NPIP-associated surveillance testing, participant training, and outreach.

There are also some examples of the national industry organizations providing some funding to improve the overall performance and capabilities of the NPIP across the country. The US Poultry and Egg Association recently funded the development of a web-based national NPIP database which is being used by the NPIP Official State Agencies to electronically permit the movement of poultry and hatching eggs between states.

How does the NPIP differ from or complement the Secure Food Supply Plan for the US poultry and egg industries?

The motivation to develop what are now known as the Secure Food Supply Plans (i.e., Secure Poultry, Secure Pork, Secure Milk, and Secure Beef) began with the Iowa Egg Producers’ interest in establishing the ability to move and sell eggs from AIV-negative premises located within a HP-AIV control area. Drs. Jim Roth and Darrell Trampel, at the Iowa State University College of Veterinary Medicine, worked closely with the Iowa Egg Producers, Iowa Department of Agriculture and Land Stewardship (Dr. David Schmitt, State Animal Health Official), and the USDA to develop and implement a voluntary program called “FAST Eggs.” This pilot program was initiated in Iowa in 2008 and eventually evolved into the current suite of Secure Food Supply Plans.

The Secure Poultry Supply Plan aims to provide flocks within HP-AIV control areas a mechanism to demonstrate freedom from AIV, and safely move non-affected poultry and egg products out of HP-AIV control zones to slaughter, sale, or on for further growing. Specifically, the Secure Poultry Supply Plan provides guidance on testing, biosecurity, and other reporting requirements necessary to demonstrate freedom from AIV at a level of confidence sufficient for state animal health officials to permit movement of poultry or egg products out of a HP-AIV control area. Overall, the Secure Food Supply Plans are technical documents designed for use and reference in preparation for and during an animal health crisis. The scope of the Secure Food Supply Plans for the US poultry industry have targeted foreign animal diseases (FADs), and HP-AIV in particular. The term ‘trade impacting disease’ (TID) will be used to be synonymous with ‘foreign animal disease’ (FAD) for the remainder of this document. The Secure Food Supply Plan documents are housed and maintained by the Center for Food Security and Public Health at the Iowa State University College of Veterinary Medicine.

Decisions to use standards set forth in the Secure Food Supply Plans to permit the movement of animals or animal products out of a trade impacting disease (TID) control area during a time of animal health crisis most generally reside with the state animal health officials (state departments of agriculture) in the affected states, including the states of destination. Such decisions are made on a state-by-state basis and are commonly situation-based decisions made in the midst of the animal health disease crisis. Due to the HP-AIV outbreaks, poultry and egg producers, poultry veterinarians, and state animal health officials in the affected regions (with HP-AIV control areas), are the only segment of the greater US livestock and poultry industries with any first-hand experience in utilizing elements of the Secure Food Supply Plans during a formal trade impacting disease (TID) response. The pre-movement AIV PCR testing requirements, along with a lack of observable clinical signs, have been the primary elements of the Secure Poultry Supply Plan utilized to support the permitted movement of birds or eggs from AIV negative premises in HP-AIV control areas to date.

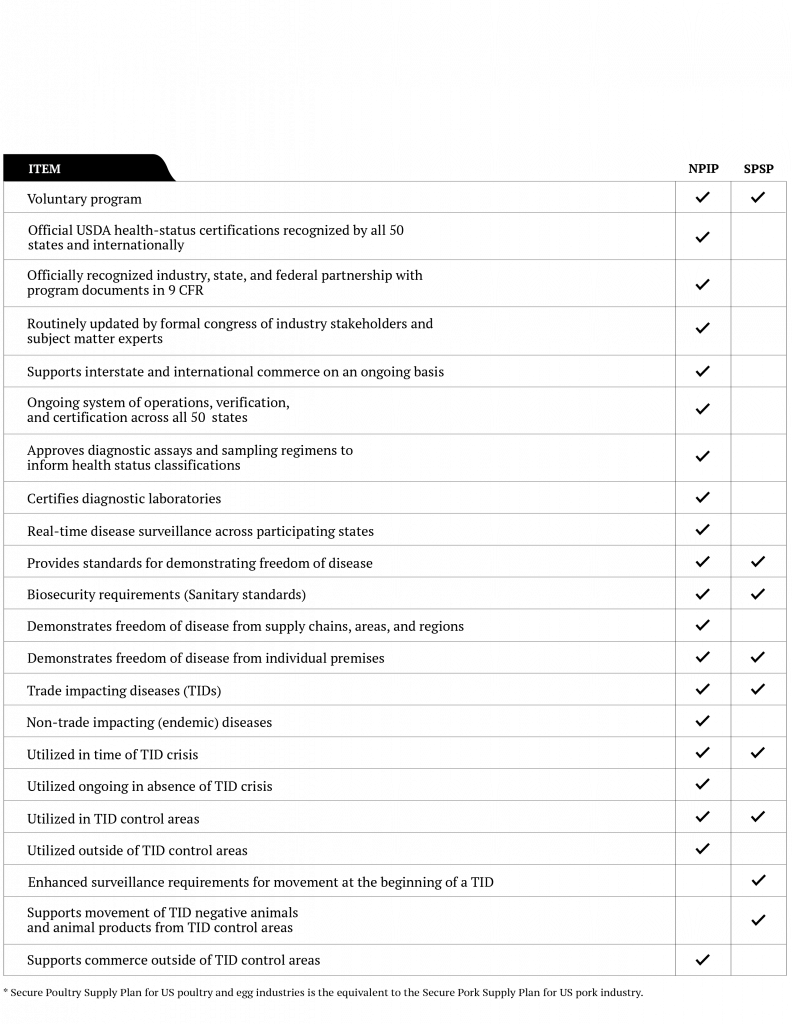

In contrast to the Secure Food Supply Plans, the NPIP is a long-standing industry, state, and federal partnership (i.e., a working organization with officially recognized documents and health status classifications and a network of ongoing implementation and certification) that provides common definitions and standards toward certifying the health of participating poultry flocks, products, and slaughter facilities across the US. The scope of NPIP health status certifications include both TIDs and non-TIDs. Thus, the NPIP provides a nationally and internationally recognized platform for flocks, slaughter facilities, and states to demonstrate freedom from a growing number of specified diseases in both peacetime and in times of animal health crisis. For example, the NPIP AIV certifications provide the foundation necessary for larger areas, regions, industry segments (subparts) and states to be recognized as H5/H7 Avian Influenza Monitored or Avian Influenza Clean. The recognition of such industry segments (subparts) and regions is a critical element in better positioning US poultry flocks and slaughter facilities in non-affected regions to maintain access to export markets and streamline interstate commerce during a time of animal health crisis in the US.

It should be appreciated that NPIP health status certifications are distinct from (but complementary with) the Secure Food Supply Plans for the US poultry and egg industries. The Secure Food Supply Plans aim to help sustain continuity of business by keeping unaffected animals and product moving through the production cycle and onto market during the time of an animal health crisis. In contrast, the NPIP provides a well recognized platform for demonstrating freedom from AIV across flocks, hatcheries, slaughter facilities, states and regions in support of helping non-affected regions, industry segments (subparts), or states access to export markets and facilitates ongoing interstate commerce. A more complete listing of some key differences, similarities, and synergies between the NPIP and the Secure Poultry Supply Plan are shown in Figure 11.

- National Poultry Improvement Plan Website. Available at: www.poultryimprovement.org. ↵

- Reynolds E. Iowa Poultry Association (Official State Agency of the NPIP for Iowa). Personal interview, August 6, 2018. ↵

- Brennan P, Kopp M, Lenz S, Marsh B. Indiana State Poultry Association (Official State Agency of the NPIP for Indiana), Indiana Board of Animal Health, Indiana Animal Disease Diagnostic Laboratory, and Purdue University, Personal interview, August 21, 2018. ↵

- Gharaiben S, Lauer D, Pollock S, Voss S. Minnesota Poultry Testing Laboratory (Official State Agency of the NPIP for Minnesota), Minnesota Board of Animal Health, and University of Minnesota. Personal interview, August 28, 2018. ↵

- Waltman D. Georgia Poultry Lab Network (Official State Agency of the NPIP for Georgia). Personal interview, September 19, 2018. ↵

- Heard D, Hegngi F, Lindsey C. National Office of the National Poultry Improvement Plan, Conyers, GA. Personal interview, September 20, 2018. ↵

- Center for Food Security and Public Health (CFSPH) and USDA-APHIS. National Veterinary Accreditation Program Module 17: National Poultry Improvement Plan (NPIP). Available at: https://nvap.aphis.usda.gov/NPIP/index.htm. ↵

- Center for Food Security and Public Health (CFSPH) and USDA-APHIS. National Veterinary Accreditation Program Module 17: National Poultry Improvement Plan (NPIP). Available at: https://nvap.aphis.usda.gov/NPIP/index.htm. ↵

- National Poultry Improvement Plan Website. Available at: www.poultryimprovement.org. ↵

- National Poultry Improvement Plan Website. Available at: www.poultryimprovement.org. ↵

- National Poultry Improvement Plan (NPIP) Biennial Conference. Franklin, TN. June 26–28, 2018. Biennial presentations available at: http://www.poultryimprovement.org/default.cfm. ↵

- National Poultry Improvement Plan Website. Available at: www.poultryimprovement.org. ↵

- National Poultry Improvement Plan (NPIP) Biennial Conference. Franklin, TN. June 26–28, 2018. Biennial presentations available at: http://www.poultryimprovement.org/default.cfm. ↵

- National Poultry Improvement Plan (NPIP) Biennial Conference. Franklin, TN. June 26–28, 2018. Biennial presentations available at http://www.poultryimprovement.org/default.cfm. ↵