Relevance and Considerations of Study Findings to US Pork Industry

What are some key differences and commonalities between the US pork and US poultry and egg industries?

When considering the relevance of the NPIP to the US pork industry, it is important to acknowledge both the key differences and commonalities that exist between the US pork industry and the US poultry and egg industries.

There are many biological and life cycle differences between poultry and swine. Such differences are key drivers in the dissimilarities between poultry, egg, and pork production and in the animal health challenges facing the respective industries. In general, the production cycle is shorter and the economic value of individual animals lower in poultry than in swine or other livestock species. Although there is arguably more diversity among the various types of commercial and non-commercial poultry and egg operations (e.g., layers, broilers, turkey, ducks, upland game birds, hobbyist breeding poultry), the commercial segments of the US poultry and egg industries (Breeding and Commercial Poultry) are generally more consolidated and vertically integrated than the commercial US pork industry. Interstate movement of poultry and swine for further growing and harvest are common and done en masse on a daily basis. However, Commercial Poultry supply chains tend to be more regional compared to their counterparts in the US pork industry.

Endemic diseases of high consequence (most notably viral diseases) are less impactful in commercial poultry operations (Breeding and Commercial Poultry) than in US Breeding Swine. The long-standing NPIP-related efforts to eliminate a vertically transmitted disease of significance from Breeding Poultry and the ability to remove the fertilized eggs from the hens prior to hatching (i.e., offspring are not exposed to infected females) are both significant factors in reducing the impact. Unwarranted lateral introductions of endemic diseases of high consequence into Breeding Poultry are rare events, as compared to the frequency of such episodes in US Breeding Swine.[1] That is, the infectious disease dynamics and risk for the introduction of endemic diseases of high consequence into breeding stock (most notably viruses) differ greatly between commercial swine and poultry operations in the US. The apparent differences in the level of risk and observed occurrences for laterally introducing diseases of high consequence into breeding stock may be one of the most significant health related differences.

However, the US pork industry has evolved in a direction that increasingly shares more commonalities than differences with the US poultry and egg industries. Commonalities include multi-site production, rearing animals in climate-controlled and bio-secure facilities, repeating systems of rearing, production, and inter-premises distribution of animals (supply chains), utilization of population medicine-based approaches towards controlling the health or pathogen status of herds or flocks, and an ever-increasing level of association between the slaughter plants and their suppliers of animals for harvest. The US pork and the poultry and egg industries have observed similar trends in the percentage of domestic production and value derived from exports (most notably in the broiler industry). This growth and corresponding dependence on maintaining access to export markets is a common and highly significant issue. The US pork and the US poultry and egg industries are under common social and consumer pressures related to housing standards, production methods employed, and use of antimicrobials. The US pork and US poultry industries are also primary competitors in the domestic and global marketplace.

Does the US pork industry have major animal health-related challenges that extend beyond the immediate influence of an individual producer, packer, or existing organization?

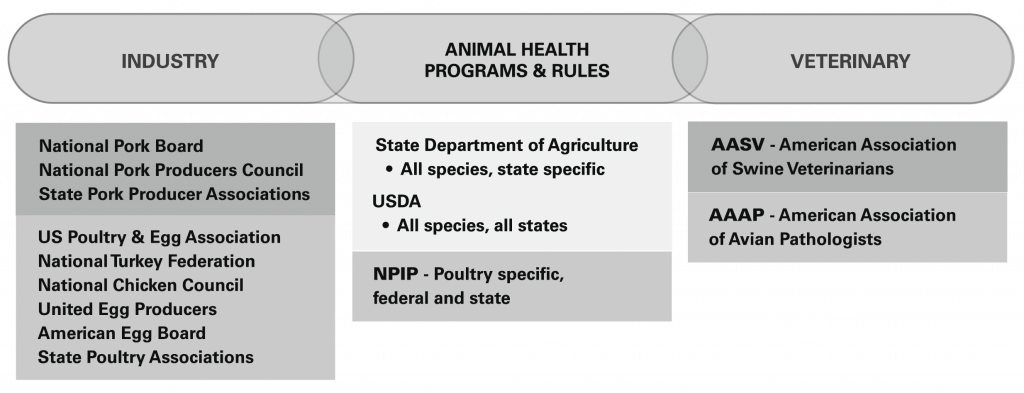

Assessment of industry need is an obvious question. The US pork and US poultry and egg industries share a number of similar species-specific animal industry and veterinary organizations (Figure 12). However, the NPIP has no peer in US animal agriculture. The NPIP is the only industry, state, and federal partnership in the US focused on species and industry specific animal health-related programs, definitions, standards, and rules. The NPIP is also unique in that its program definitions and standards are officially recognized at both state and federal levels.

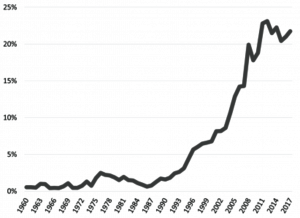

Trade impacting disease (TID) risks

The US pork industry has grown increasingly dependent on export markets over the past 25 years (Figure 13).[2] TID-related market risks and recurring endemic diseases of high consequence present major animal health challenges to all segments of today’s export-centric US pork industry. While the total amount of pork produced in the US has grown by approximately 100% since the mid-1970s, domestic consumption per capita has remained relatively unchanged.[3][4] Thus, a significant portion of the growth in the US pork industry since the early 1990s has been due to the purchase of pork by consumers outside of the US. Approximately 23% of US pork is exported on a carcass-weight basis, a 10-fold increase over historical averages. This growth in exports not only increases the demand for more tonnage of pork to be produced, but also significantly enhances the value of each pig sold via the distribution of the various parts, cuts, and products for sale to markets throughout the world. Since 2012, exports have represented more than 30% of the market value realized by US pork producers. Exports are one of the most significant factors, outside of demand growth in the US, influencing the overall size and profitability of the US pork industry. Estimates in recent years suggest that export markets add approximately $50 of value to each market hog sold in the US.[5]

The growth in (and resulting dependence on) export markets comes with a markedly different level of TID and geopolitical market risks. While geopolitical risks are beyond the scope of this report, animal health-related risks affecting access to export markets are very real and highly consequential. The internationally-recognized guidelines and standards related to the effect of animal health on the international trade of animal-based food products are established by the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE). OIE standards are widely recognized by willing and interested trading partners throughout the world. African Swine Fever (ASF), Classical Swine Fever (CSF), and Foot and Mouth Disease (FMD) are the three most relevant TIDs for swine. OIE guidelines generally prohibit the exportation of fresh pork products from regions or countries with commercial livestock operations infected with or vaccinated for ASF, CSF, or FMD. Thus, an outbreak of any of these three TIDs in the US can be expected to result in the immediate cessation of fresh pork exports. While each trading partner can make their own decisions on the importation of pork (irrespective of the ASF, CSF, or FMD status of the country or region of origin), the US commonly accepts and follows the standards set forth by the OIE. Likewise, US trading partners are likely to follow OIE guidelines for international trade, irrespective of the health status of US swine.

Clearly, a sudden cessation in US pork exports would have a dramatic and far-reaching impact across all segments of the US pork and related industries. Foreign animal disease preparedness is frequently discussed, but rarely results in tangible action(s) or measurable outcome(s). Managing the risk of TIDs is extraordinarily complicated, larger than any single approach, and beyond the ability of any individual, organization, or institution to control. Prevention, Response, and Recovery are each unique and critical components in managing the risk of TIDs. While Prevention and Response get much needed attention, Recovery efforts designed to demonstrate freedom from disease and reestablish export markets in officially recognized regions are often overlooked, despite the fact that Recovery from a TID incursion affecting the US pork industry is far more likely to be measured in months and years than in weeks.

Currently, there is no clearly documented, officially recognized, active (i.e., inclusive of officially enrolled and certified participants and premises), and ongoing program for the US pork industry that is ready to be rapidly scaled-up to support regionalization efforts following the detection of a TID in US livestock. The absence of a pre-existing and officially recognized system ready to establish evidence of freedom from a TID following the initial incursion and throughout the Recovery phase represents a significant risk to the entire US pork industry. Additionally, there is a general lack of understanding, clarity, and/or broadly understood dialogue as to the specifics related to response plans, indemnity eligibility, and payment for the producers initially affected by a TID requiring quarantine or mass euthanasia. Such lack of clarity among industry stakeholders creates an additional level of uncertainty, delays purposeful actions, and contributes to further disease spread because of delays in responding to a TID event.

Recurring endemic diseases (REDs) of high consequence

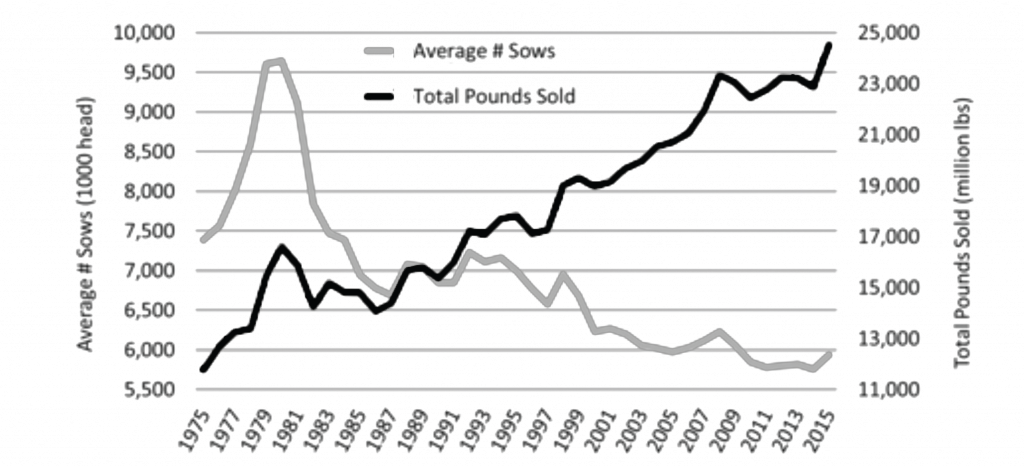

Levels of productivity in the US pork industry have continuously improved over time. Today, US pork producers generate about twice as much pork with 20% fewer sows than producers 40 years ago (Figure 14).[6][7] Likewise, tremendous progress has been made in the ability to confidently, repeatedly, and cost-effectively control or eliminate diseases of high consequence from individual farms and production networks. Much of this knowledge and capability has its origins in the US pork industry’s now 30-year-long effort against the effects of Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus (PRRSV). The recent lessons learned from the US pork industry’s Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus (PEDV) experience have also been insightful. The myriad of highly collaborative public/private research efforts and information sharing among veterinarians, pork producers, and researchers has greatly enhanced the understanding of the means by which diseases can be introduced into swine farms. In particular, there is a clearer understanding and appreciation for disease movement between farms via means other than the conventional routes of infected pigs and contaminated semen (e.g., transport vehicles, fomites, insects, feed, and aerosol transmission).

Such knowledge has prompted a previously unprecedented investment in biosecurity-related infrastructure and procedural related methodologies. These biosecurity investments have most appreciably been focused on reducing the risk of disease introduction into boar studs, breeding herds, and breeding stock replacement farm sites. Similarly, there have been great advances in the understanding of the shed and spread (circulation and transmission) of pathogens within a given farm site or premises. Such understanding has led to the now common health management practice of coupling breeding herd closure with strict all-in all-out (AIAO) pig flow and good sanitary procedures in farrowing facilities to eliminate a growing number of diseases from stand-alone breed-to-wean farms. In short, the ability to effectively diagnose and eliminate many infectious diseases of high consequence, without having to depopulate the breeding herd, from individual or related farm sites with AIAO pig flow is generally good.

However, the capabilities and advances outlined above have not translated to sustained success in containing or eliminating emerging or recurring endemic diseases (REDs) of significance (e.g., PRRSV, PEDV, and Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae) across broad areas or regions of the US. The recurring costs and many challenges associated with mitigating and managing the growing number of contagious REDs of high consequence represent a long-standing challenge to the US pork industry. The infectious disease burden and ongoing recirculation of such diseases is most evident in regions with significant growing pig populations. Disease transmission within and between commercial growing pig farm sites is common and provides a reasonable environment for diseases (most notably viruses) to be maintained and indirectly moved both locally and across vast distances to infect susceptible breeding stock.

The applied research efforts conducted by Lowe et al., shed great light as to how much cross- contamination of livestock trailers is occurring at the interface of the trailer and unloading dock at slaughter facilities. In essence, this research found that there were approximately 1.4× (3.35× higher risk if the immediate previous trailer was positive) more PEDV-positive trailers leaving the plant as there were coming into the plant.[8] This work strongly suggests un-sanitized trailers returning from slaughter plants are likely be a significant amplifier of PEDV via the unintended consequences of dragging virus back from the slaughter plants to unsuspecting groups of susceptible finishing pig populations. Such finishing pigs are more than capable of amplifying the virus in great numbers. These late-term finishing breaks of PEDV commonly associated with live haul transportation infections have also revealed the risks that high volumes of virus being shed late in finishing has on the subsequent groups of weaned pigs being placed into the same wean-to-finish facilities, most notably in winter months. It would seem highly probable that this same type of inter-herd transmission associated with finishing pig live haul is also occurring with other diseases of high consequence; albeit the acute clinical consequence of many other diseases in growing pigs (as compared to PEDV) can often be less visually obvious and/or delayed from the actual point of infection.[9] In short, the continuous area/regional spread of endemic diseases of high consequence are a very real and consequential challenge impacting the health of US swine. Such recurring disease challenges contribute to the ongoing investment in biosecurity and other preventative disease measures, increased costs of production, negative impacts on animal well-being, employee turnover, antimicrobial use, and ultimately the longer-term competitiveness in the broader global animal protein marketplace. There is limited historical precedent for the successful containment or elimination of a readily communicable disease of high consequence across broad regions of the US with significant pig populations in the absence of an officially recognized control or elimination program.

Potential roles or applications for an NPIP like program for US pork industry

As noted above, NPIP’s primary role since its inception has centered on bettering the health of US poultry through the control and elimination of specific diseases in Breeding Poultry.

Breeding Poultry have long used the NPIP health status classifications as a means of representing the health of their flocks and offspring at points of sale, exhibition, interstate movement, and international trade. The resulting industry expectations, demands, and requirements for obtaining birds from Breeding Poultry free of the specified vertically transmitted disease of high consequence continues to have a dramatic impact on the overall health and productivity of US Commercial Poultry. NPIP’s more recent (2006) divergence and expansion to include the H5/H7 Avian Influenza Monitored classification for Commercial Poultry plays a significant role in mitigating the TID-related market risks for the US poultry and egg industries.

Mitigating TID risks and providing a framework to facilitate larger-scale improvements in the health of US swine at a level beyond the reach or immediate influence of any individual pork producer or packer are potential applications of an NPIP like program (i.e., US Swine Health Improvement Plan) for the US pork industry. Collectively, this aim would serve to enhance the competitiveness and sustainability of the US pork industry in the domestic and global marketplace.

NPIP’s approach toward mitigating AIV-related market risks via the establishment of the H5/H7 Avian Influenza Monitored classification for Commercial Poultry and Avian Influenza Clean status for participating states would have significant value to the US pork industry in the event of an introduction of a TID such as ASF, CSF, or FMD. An officially recognized program, with health status classifications and standards to demonstrate freedom of specific TIDs in commercial pork production operations supplying slaughter facilities (supply chains) across states or regions, would be a valuable system to have in place during the Recovery phase of a TID outbreak. It should be understood diagnostic testing, traceability requirements, and sanitary standards are each critical components necessary for demonstrating evidence of freedom across supply chains, industry segments, areas, and regions.

OIE-level compartmentalization is not likely feasible for the vast majority of commercial pork production operations, given the complexity, costs, and requirements of the process. However, there is long-standing precedent domestically and internationally for trading partners to recognize states and regions as free of said diseases in affected countries (i.e., regionalization). The preemptive establishment of a USDA-certified program recognized and supported by participating states could provide the basis for scaling up the necessary testing in the advent of an outbreak to support efforts to demonstrate freedom of disease across specified market segments and legally recognized states and regions (regionalization). As mentioned earlier, well defined traceability and sanitary standards need to accompany the specified diagnostic testing requirements to sustainably support evidence of freedom across supply chains, industry segments, areas, and regions. In the same way as establishing common definitions and standards for establishing officially recognized health status classifications and/or demonstrating freedom of TIDs, a US Swine Health Improvement Plan could also provide the framework to make larger scale progress towards mitigating the effects of recurring endemic diseases (REDs) of high consequence across supply chains, industry segments, regions, and states.

Establishing a US Swine Health Improvement Plan may also be useful in advancing baseline traceability and sanitary (biosecurity) practices and standards that indirectly impact all commercial pork production operations in the US. Traceability and baseline sanitary (biosecurity) standards are critical elements in foreign animal disease preparedness (Prevention, Response, and Recovery), as well as in mitigating REDs of high consequence across areas and regions. Systems of traceability and sanitary standards associated with transporting commercial swine for breeding, further growing, or to points of concentration, are hallmark components of similar swine health programs implemented in Denmark and the Netherlands. The systems of traceability and live haul transportation sanitary standards implemented are irrespective of any pathogen specific claims, but represent core elements of their respective swine health programs.[10][11] The Danish and Dutch pork industries are heavily dependent on export markets, have significant populations of pigs in a relatively small geography, and have limited options for the use of antimicrobials.

NPIP provides the US poultry and egg industries a very structured, purposeful, and democratic forum of industry stakeholders, official state agencies, and the USDA to discuss, debate, and address issues of poultry health that have broad impact across the various segments of the US poultry and egg industries. Topics of discussion range from creating officially recognized differentiations between commercial and non-commercial poultry operations, determining the requirements for the various health status classifications, approving officially recognized diagnostic tests or regimens, to updating indemnity policies, eligibility, and payment rates. NPIP’s operational structure creates an ongoing forum for substantive and interactive dialogue, learning, awareness, understanding, and informed perspective, on issues specifically related to poultry health across industry stakeholders, states, and the USDA that would not otherwise occur across such a broad and representative body of industry stakeholders. Creating such a forum on US swine health among industry stakeholders, states, and the USDA would be another reason for establishing a US Swine Health Improvement Plan.

Potential structure of a US Swine Health Improvement Plan

The basic tenets of NPIP’s operational structure is one option, but a US Swine Health Improvement Plan could be established and operate under a different structure, depending upon the interests and desired outcomes of US pork industry stakeholders. Thus, a US Swine Health Improvement Plan could be developed and operated within the framework of the national and state pork industry organizations, through the creation of a new stand-alone private entity, or approached in a state-by-state manner via collaborative efforts between the pork producers, processors, and state department of agriculture (state animal health official) within a given state.

Developing and operating such a voluntary program within the framework of the existing national and state pork industry organizations or as a new stand-alone private industry entity would most likely provide for the most flexibility. There is clear precedent for facilitating and implementing voluntary pork quality assurance programs within the framework of the national and state based pork industry organizations.

Similarly, there is a long-standing precedent and history for leaders (e.g., program staff, members, and swine health committees) representing the national and state pork industry and swine veterinary organizations to routinely collaborate with, and provide industry perspective on, issues related to swine health to the respective USDA APHIS and state animal health officials. The swine health committees of the national and state pork industry organizations were intimately involved in collaborating with the USDA and their respective state animal health officials in the development of the program policies and procedures utilized to eliminate Pseudorabies virus (PRV) from the US on a state-by-state basis.

A private entity could be created for such a purpose with a board of directors to provide advisement, and operate the program in accordance with some type of recognized ISO (International Organization for Standard) like standard inclusive of the necessary third-party verifications.

The limitation of either of these “industry only” options is that any such efforts to claim an officially recognized health status across a given state or region (group of counties or states) would ultimately need to be endorsed by the state animal health official (state departments of agriculture) in each state making such a specified claim. The definitions and standards being used to make such claims of status would also need to be recognized by the USDA. State animal health officials (state departments of agriculture) are the responsible entities for representing regional based claims of health status in each state, whereas the USDA is often the responsible party for representing the health status of any collection of states, regions, or the entire US to international trading partners.

Producers and processors, in conjunction with their respective state animal health official (state departments of agriculture), could forge their own state-specific Swine Health Improvement Plans. A state-specific program would carry the benefit of having official recognition and impact within a given state. However, the utility and recognition of such standards, definitions, and health status classifications would likely be limited to and be unique to each state. It should be understood that the vast majority of animal health standards, rules, and authority resides within each state (e.g., state animal health official and state department of agriculture).

Modeling the operating structure of a US Swine Health Improvement Plan after the basic tenets of NPIP’s existing structure would carry the benefit of having a precedent and a working model that is well understood within the USDA and across all 50 states (e.g., state animal health officials and departments of agriculture). NPIP’s basic tenets include being informed and routinely updated by a democratic forum of industry stakeholders, facilitated by the USDA, adopted and implemented on a state-by-state basis by official state agencies, and voluntary to participants. NPIP’s cooperative industry, state, and federal partnership model also lends itself toward having more consistency across states and for having officially recognized health status classifications across supply chains, industry segments, regions, and states that are broadly supported and recognized by state animal health officials, USDA, and international trading partners.

What would be required to establish a US Swine Health Improvement Plan?

Moving this idea forward would require a collaborative, concerted, and sustained effort by US pork producers and pork processors interested in exploring, creating, and potentially participating in a US Swine Health Improvement Plan. The specific hurdles and milestones would largely depend on the approach (industry only vs. some type of formal industry, state, federal collaboration) and scope (state-specific plan vs. plan for use across states). Interests among pork producers and packing plants (supply chains) in one or more states would be the foundation needed to build this concept. Should there be interest in wanting to claim or defend a specified health status among commercial pork producers and packing plants (supply chains) within a given state or region, targeted outreach and a formal collaboration with the appropriate state animal health officials and the USDA would be critical. Federal and state level legislation would not be required to establish a voluntary program, but a significant push from interested US pork industry stakeholders, a core group of interested states, and approval by USDA APHIS leadership, would be required to move forward with a program officially recognized and/or facilitated by USDA APHIS. Adoption and participation in a USDA-affiliated program would be on state-by-state and participant-by-participant basis.

What would be the potential benefits and liabilities for establishing a US Swine Health Improvement Plan modeled after the basic tenants of NPIP’s industry, state, and federal partnership?

Benefits

Reduce trade impacting disease (TID)-related market risks

Establishing officially recognized health status classifications and well-defined systems and standards for demonstrating freedom of TIDs from commercial pork production farm sites and slaughter facilities across states and regions would be immediately helpful in the event of the discovery of a TID in the US. Proactively developing and implementing an industry-informed and functional system prior to a “TID event” would enable participants and states to readily scale up the necessary testing to demonstrate freedom of disease across specified regions and market segments throughout the Recovery Phase. As mentioned earlier, there is precedent for willing trading partners to recognize specific areas (regionalization) as being free of specified diseases within an affected country. Recognizing the health status of commercial livestock by region (counties, states, or provinces) has long been a critical component of making stepwise progress over the course of large-scale disease control or eradication efforts domestically and internationally.

Creating such a body and working system to establish and maintain officially recognized health status certifications across herds, supply chains, processing plants, areas, states, and regions could also provide a means of advancing traceability and sanitary standards across the US pork industry. Traceability and biosecurity are critical elements to all aspects of TID preparedness (Prevention, Response, and Recovery). On-farm biosecurity practices and sanitary standards associated with transporting swine for breeding, further growing, or to or from points of concentration, are critical control points for mitigating the spread of diseases of high consequence into and between farm sites. The infrastructure and systems necessary to consistently sanitize (i.e., clean or decontaminate) the masses of live haul trailers departing points of concentration are a well-recognized and costly animal health infrastructure-related challenge facing the US pork industry. The previously cited applied research completed by Lowe et al.[12] might indirectly suggest that live haul trailer sanitation may be one of the most critical elements in mitigating the unwarranted spread of a TID following an introduction into the US.

A more formal approach toward actively maintaining a current and up-to-date list of all commercial swine farm premises, and an officially recognized health status for one or more pathogens endemic to US swine, for all commercial farms across a state or sizable region, has not occurred since the PRV eradication program in the late 1990s and early 2000s.[13] The infrastructure for doing so across states has long since diminished. While the information management infrastructure used over the course of the PRV control and eradication effort involved many people and much paper, establishing a working system for maintaining an up-to-date list of premises, officially recognized health status(es), and swine movement information utilizing the information technologies of today, would be of tremendous benefit in any type of disease monitoring, response, control, recovery, or elimination effort. Fundamental and broadly applicable advances in traceability and biosecurity are infrastructure- and coordination-intensive endeavors with no short-term solutions. Instituting an active, working, and continually improving US Swine Health Improvement Plan could provide a platform for tangible progress toward enhancing all three phases of TID preparedness (Prevention, Response, and Recovery) across broad segments of the US pork industry.

Establishing a US Swine Health Improvement Plan would also prove useful in expediting the development and approval of well-informed and practical diagnostic testing regimens for demonstrating freedom of diseases in US Swine. Developing and approving diagnostic tests, sample types, and sampling strategies has long been central to NPIP’s mission. Such regimens play the central role in conferring NPIP health status classifications. Establishing and approving well-characterized diagnostic assays and practical testing regimens enhances the quality, consistency, and cost-effectiveness for conferring officially recognized health status classifications. Such efforts create consistency and set broadly recognized precedent and standards for specified health status classifications across farm sites, processing plants (supply chains), states, and regions. The collaborative nature of the industry, state, and federal partnership in approving diagnostic assays and testing regimens through the NPIP Technical Advisory Committee, composed of subject matter experts from throughout the US, has a long track-record of delivering practical and cost-effective diagnostic standards for officially-recognized health statuses in the US poultry and egg industries.

Facilitate larger scale efforts to mitigate the impact of recurring endemic diseases (REDs) of high consequence on US Swine

The same systems, structure, and approach for establishing officially recognized health status classifications across individual herds, packing plants (supply chains), regions, and states for TIDs could also be used as a pathway or platform for making stepwise progress toward mitigating the impact of specified recurring endemic diseases (REDs) of high consequence (e.g., PRRSV, PEDV, Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae) to US Swine. In addition to area regional or system specific disease monitoring or control applications, establishing officially recognized standards for representing the health status of Breeding and Growing Swine could be useful as a means of representing the health status of the stock at a point of sale or transfer. Similarly, advances in traceability and biosecurity (sanitary standards) would better position the US pork industry for making larger scale progress toward mitigating the impact of endemic diseases of high consequence. Reducing the impact of REDs of high consequence would ultimately improve the health of US swine and longer-term competitiveness of the US pork industry in the global animal protein marketplace.

Create and empower an officially recognized forum to inform and address federal and state agency policies, procedures, programs, or standards relating to US Swine health

Establishing a US Swine Health Improvement Plan modeled after the NPIP would create a formal, structured, and broadly represented democratic forum to engage in meaningful dialogue and directly influence swine health related programs and policies of high relevance to the US pork industry. NPIP has shown that substantive and focused dialogue shared among industry stakeholders (program participants), state agencies, and USDA can create an environment for more informed, timely, practical, and purposeful decisions to be made and industry impacting outcomes achieved.

As stated previously, the NPIP has no peer in US animal agriculture (Figure 12). The US poultry and egg industries’ long-standing engagement in the NPIP provides a unique position in that this broadly represented group of industry stakeholders (i.e., NPIP participants, NPIP Technical and General Conference Committee members, and voting delegates at the NPIP Biennial Conference) play a very direct role in forming, discussing, and addressing issues, definitions, and policies related to poultry health that have far reaching impact across the US poultry and egg industries. Such an empowered forum creates an opportunity for dialogue, movement, decision-making, and action on poultry health issues that extend beyond the influence of individual producers, processors, or states. The active and highly applied nature of the NPIP continually tests the relevancy of the program and requires the program to be continually updated and improved to address the changing needs of the industries (subparts) served. Topics can range from those directly included in the NPIP, to tangential poultry health-related items in which the USDA plays a role, such as TID response, indemnity policies, vaccine needs, and interstate and international commerce. NPIP’s industry, state, and federal partnership model is also unique in that its outcomes influence both federal and state level standards, definitions, and policies.

In contrast, the absence of an industry-driven and empowered body to establish nationally recognized definitions for swine health sets the stage for a state-by-state patchwork of local standards and definitions. This patchwork lacks the nationally- and internationally-recognized credibility needed to support pork exports from unaffected regions during a time of crisis. In short, the NPIP model of shared governance shifts much of the burden and responsibilities for developing, updating, and implementing swine health related standards, definitions, policies, and rules from the federal and state animal health agencies to an empowered body of industry stakeholders. Based on the history of NPIP, this approach would better position industry stakeholders to influence issues related to safeguarding, improving, and representing the health of US swine.

Outside of the poultry and egg industries, the US livestock industries and federal/state animal agricultural agencies are essentially one generation away from having participated in a large-scale disease control or eradication program. Given the minimal routine interaction between industry stakeholders and the federal and state agencies that exists in the absence of such a program, a “disconnect” and misunderstanding of the resources and capabilities available in such agencies naturally develops. While the US is fortunate in having the service of many capable and committed professionals in our state and federal animal health agencies, their resources are very limited as compared to the capabilities, capacity, and species-specific knowledge that resides in the industries being supported by such agencies. It should also be understood that such agencies are responsible for animal health programs, policies, and capabilities across many species and types (commercial and non-commercial) of livestock, poultry, equine, aquaculture, commercial companion animal breeding operations, and farm-raised cervids, mink, and other minor species. Initiating a US Swine Health Improvement Plan modeled in NPIP’s likeness would better leverage the expertise and capabilities that exists among US pork industry stakeholders in addressing the grand animal health related challenges facing the US pork industry.

Liabilities

Time and money

Much of the energies and resources required to develop and implement an NPIP like program for the US pork industry would be additive to the status quo. There may be an opportunity to leverage some of the resources within USDA and participating states’ departments of agriculture. Should the development of a US Swine Health Improvement Plan result in stepwise improvements in the systems of traceability utilized for monitoring swine movement and keeping premises level information current on an ongoing basis, these would be examples of where existing resources could be redirected, conserved, and improved. One recent success story of traceability-related efficiencies in the NPIP was the US Poultry and Egg Association’s funding of a web-based application used by the NPIP Official State Agencies to permit the interstate movement of poultry. However, the vast majority of the work and costs would be additive and borne by the participating states and participants. As stated earlier, NPIP Official State Agencies and NPIP participants carry the primary burden for maintaining, continuously improving, and implementing the NPIP. Initiating and implementing a US Swine Health Improvement Plan would require much industry driven leadership, time, sustained effort, and resources.

Uncomfortable discussions among peers and industry stakeholders

Deriving workable definitions, standards, policies, guidelines, or rules that are agreeable among any group of people in a democratic forum is not easy under any circumstances. Even when its members are all on the same team, share common interests, motivation, expertise, and goals for the long-term success of the industry and stakeholders they represent, democracy is not easy. NPIP’s Biennial Conference convenes to make decisions on program definitions, standards, and policies that have ongoing consequences on the health of US poultry and the US poultry and egg industries. The positive aspect is that such decisions are being driven, debated, and decided upon by industry stakeholders that share a common interest in the sustainability and success of the various states and segments of the US poultry and egg industry they represent. Thoughtful debate, compromise, practical and workable decisions, and error on the side of simplicity and flexibility, are common. The NPIP has been called a “democratic regulatory program” in which the producer is both the primary beneficiary and decision maker of the programs content and direction.[14]

Consequences of having requirements, standards, or rules

Obtaining and maintaining a recognized certification or classification that involves an individual or entity to meet or comply with a specified set of requirements has consequences. Consequences of achieving or complying with any type of prescribed minimum standards or rules can be positive, negative, operational, financial, or unintended in nature. The benefits of any decision, standard, practice, or participation in a program with specified requirements ultimately has to be weighed against its costs and consequences.

For most practical purposes, since the eradication of PRV from the US in 2004, there are few examples of specified health status, sanitary (biosecurity) practice, or vaccination related requirements or regulations having a significant impact on commercial pork production operations in the US. Thus, there is limited recent experience with legally binding constraints on day-to-day operations concerning pig movement or particular management practices due to the health status of individual farm sites or the status of the area or region of origin or destination. Such flexibilities and freedom of choice are highly valued. Over this same time, there has been a previously unprecedented amount of investment, proactive efforts, and management practices implemented by pork producers to protect and improve the health, productivity, and profitability of their operations.

The substantive investments in biosecurity-related infrastructure, siting of breeding stock in less pig dense locations, extensive acclimation and vaccination practices, and pathogen elimination efforts have largely been driven in efforts to reduce the impact of recurring endemic diseases (REDs) of high consequence (e.g., PRRSV, PEDV, and Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae) in US swine. These ongoing investments and health improvement practices and initiatives are at the sole discretion of each individual producer. In broad terms, industry-standard biosecurity related practices and efforts to prevent disease introductions into US Breeding Swine are among the highest in commercial livestock production globally. Such investments have come about in efforts to reduce the incidence of unwarranted lateral introductions of REDs of high consequence into breeding stock. Unwarranted lateral introductions of endemic diseases of high consequence outside of the conventional routes of introducing infected animals or semen continue to be significant and ongoing challenge.

- El-Gazzar M, Sato Y. Department of Veterinary Diagnostic and Production Animal Medicine, Iowa State University. Personal communication. 2018. ↵

- Schulz L. Department of Economics, Iowa State University. Personal communication. 2018. ↵

- National Pork Board. Pork Quick Facts. Available at: https://www.pork.org/facts/. ↵

- USDA. National Animal Statistics Service. Available at: https://www.nass.usda.gov/. ↵

- US Meat Export Federation. Latest Export Results available at: https://www.usmef.org/news-statistics/press-releases/november-beef-exports-remain-on-record-pace-headwinds-weigh-on-pork-exports/. ↵

- National Pork Board. Pork Quick Facts. Available at https://www.pork.org/facts/. ↵

- USDA. National Animal Statistics Service. Available at: https://www.nass.usda.gov/. ↵

- Lowe J, Gauger P, Harmon K, Zhang J, Connor J, Loula T, Levis I, Dufresne L, and Main R. Role of transportation in spread of Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus, United States. Emerging Infectious Disease. 2014. 20(5): 872–874. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2005.131628. ↵

- Main R. This is our time, the choices are yours. Proceedings of the 49th Meeting of the American Association of Swine Veterinarians (AASV). March 3–6, 2018. ↵

- Dahl J, Danish Agriculture and Food Council, Denmark, and Kjaer J, Boehringer-Ingelheim, USA. Personal interview, October 17, 2018. ↵

- van Dobbenburgh R, (Henry Schein), van Eijden G, (Dierenartsen Animal Care), Netherlands. Personal interview, October 30, 2018. ↵

- Lowe J, Gauger P, Harmon K, Zhang J, Connor J, Loula T, Levis I, Dufrense L, and Main R. Role of transportation in spread of Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus, United States. Emerging Infectious Disease. 2014. 20(5): 872–874. ↵

- Anderson LA, Black N, Hagerty TJ, Kluge JP, Sundberg PL. Pseudorabies (Aujeszky’s Disease) and Its Eradication: A Review of the U.S. Experience. USDA-APHIS Technical Bulletin. 2008. No. 1923. Available at: https://www.aasv.org/documents/pseudorabiesreport.pdf. ↵

- Brennan P, Indiana State Poultry Association (Official State Agency of the NPIP for Indiana), Personal communication. 2018. ↵