Chapter 1. The Adaptive Apparel Designer’s Guide to Research

Introduction

Chapter 1 covers the first step of the design process—research, with specific attention to how it can be conducted for the adaptive apparel market. Types of research addressed include market analysis, consumer research, and materials research. In the section on market analysis, we provide a brief historical overview of adaptive apparel, identify major categories of available adaptive apparel products, and point out gaps in the adaptive apparel market. Resources that will aid designers in their research process include sections on (a) descriptions of disabilities and their impact on dressing and clothing needs, (b) an illustrated glossary of clothing adaptations organized by wearer’s needs, and (c) a client communication guide. Finally, a section on selecting the right textile for adaptive apparel needs rounds out the research process.

Research: Collect Relevant Information

Apparel design research involves market analysis research, consumer research, and materials research. The following sub-sections will briefly describe how research informs and guides the apparel design process.

Market analysis

Market analysis research is important to the apparel design process as it helps the designer to understand what products exist in the market and gaps to be filled. Designers can use the internet to identify existing products and consumers’ views of these products. Information may come from retailers’ websites, customer reviews on these websites, and other social media or blogs.

Consumer research

Consumer research is important to the apparel design process as it helps the designer understand the potential product users and their needs. Designers can research the size of the market and user needs. They can use research data from government and organizations relevant to their product. They may also seek information directly from users through interviews, focus groups, or surveys.

Materials research

Materials research is important to the apparel design process as it helps the designer identify potential materials to use in the product. It can also help them evaluate and choose among material options. Designers may use the internet to identify retailers of fabrics and notions. Designers may utilize textile testing standards and methods to test potential materials for viability in the intended use. Information gathered in the market analysis, and consumer research may be useful in understanding what materials are currently used, how consumers evaluate them, and what unmet consumer needs may exist regarding materials.

Market Analysis of Adaptive Apparel Brands and Products

This section of the chapter will provide a brief overview of the history of adaptive apparel followed by brands that offer adaptive apparel and some specific adaptive apparel products, which are organized by adaptive need.

Brief historical overview of adaptive apparel

Adaptive apparel is uniquely designed for people with special needs or older people with difficulty dressing. More than 40 million people in the U.S. have a disability. Specifically, approximately 14 million have difficulties with essential daily activities such as dressing. Considering the marginalized population, designing and developing specialized apparel products can meet their particular clothing needs. However, the apparel industry has believed that the adaptive apparel market represents a consumer market with limited buying power and designs that require significant customization to accommodate the consumer group with disabilities. Recently, Tommy Hilfiger® succeeded in providing mass-produced adaptive apparel products and overcame the limitations. As a result, Tommy Hilfiger® launched the first mainstream adaptive apparel line for children in 2016. The mainstream apparel brand made unique adaptations to its existing manufacturing processes to ensure adaptive design innovations. After the success of the children’s adaptive line, the brand expanded the adaptive line, including men and women.

Shortly after, with the growing awareness to include people with disabilities, other mainstream brands such as Target®, Nike®, or Zappos® entered this new market segment with their collections. Nike® introduced the Nike FlyEase shoe. Zappos® created the Zappos adaptive division for people with disabilities. Target® created the Cat & Jack children’s wear line and has expanded its adaptive offerings into other categories including men and women. Currently, the adaptive apparel market is considered a relatively new, yet quickly growing market, and is estimated to continue growing to roughly a $400 billion industry segment by 2026 (Gaffney, 2019).

Adaptive apparel brands

With growing awareness of consumers with disabilities, more and more brands, including mainstream brands, started to enter the adaptive apparel market. A wide range of factors influences adaptive apparel brands such as age, types of disabilities, or level of independence. Some adaptive apparel brands focus on older adults who experience severe levels of difficulties in dressing, so some of their products were designed for use of their caregivers. Some brands provide their own fashion collections to accommodate a particular consumer group such as wheelchair users. Future designers need to be prepared for a market encompassing diverse abilities. Researching the existing market for people with disabilities can provide examples and suggestions for adaptive features on clothing. The table below includes brands available online that offer adaptive apparel goods along with their current website links.

| Brand | Website |

| Buck & Buck | www.buckandbuck.com |

| Care | www.careapparel.com |

| Abilitee | abilitee.com |

| Special Kids Company | specialkids.company |

| Independence Day Adaptive | www.independencedayclothing.com |

| Easy Access Clothing | www.easyaccessclothing.com |

| Lift Vest | www.liftvest.com |

| Professional Fit Clothing | www.professionalfit.com |

| Simplatex | www.simplantex.co.uk |

| Silverts | www.silverts.com |

| Specialty For You | www.speciallyforyou.net |

| Wardrobe Wagon | www.wardrobewagon.com |

| Tommy Adaptive | usa.tommy.com/en/tommy-adaptive |

| Zappos Adaptive | www.zappos.com/adaptive-clothing |

Adaptive Apparel Products

There are different ways in which a designer can approach a design solution for adaptive apparel. Three of the major design adaptations commonly seen in the adaptive apparel market can be categorized as: (a) magnetic closures; (b) adjustable openings; and (c) fabric that supports sensory comforts. These three major categories are explained in more detail below, but other design approaches and considerations exist for specialized functional dressing needs.

Magnetic closures

Magnetic closures are one of the innovative approaches adopted by product developers in the adaptive apparel market. Wearers can effortlessly manipulate closures by replacing traditional buttons with magnets, making dressing easier. Magnets can be used with mock buttons to provide a classic appearance for such items as men’s dress shirts. This design feature is especially useful for people with dexterity issues that limit their limb strength, speed, endurance, and coordination (e.g., arthritis).

Tommy Adaptive, the adaptive apparel line of Tommy Hilfiger, use this feature for easy open and close. The magnetic closures that discreetly hides magnets but represents the traditional button shape.

https://youtu.be/JbnEqzB0VKU

The magnetic zipper is also one of the innovative adaptive features. This magnetic zipping system (MagZip) enables people to easily zip with one hand. This feature helps people with low dexterity. MagZip is used by brands such as Tommy Hilfiger, Moncler, and Under Armour.

Adjustable openings

Adaptive apparel brands develop their products easily wearable by designing the openings such as pant legs, sleeves, and waistbands adjustable. Snaps, Velcro, or zippers are used make the openings easily adjustable. For example, wearers can easily get in and out of pants when the waist opening is wider with an extended side slit.

Sensory comfort

Some adaptive apparel brands also focus on sensory comfort. Products currently available in the marketplace are usually made of sensory-friendly materials such as soft or stretchy fabrics or use flat seams and replace standard tags with tagless options to allow more comfort on the skin. Those apparel products target those with sensory issues who are sensitive to certain textures and materials (e.g., people with autism spectrum diagnoses).

Gaps in the market

Despite the fashion industry’s multiple commitments to and initiatives targeting greater diversity and inclusion, it’s been slow to embrace adaptive fashion (Webb, 2022, para. 2).

Even though the adaptive apparel market is expected to continuously grow, the current offerings of the market are not diversified well, and their design options are limited. In addition, as the current adaptive market focuses on the needs of those with disabilities (e.g., wheelchair users), the market still needs to consider various clothing needs to include people with various types and levels of capabilities. Future designers need to understand diverse clothing needs of people with disabilities and to be prepared to create fashionable and functional clothing for all.

Disabilities’ Impact on Dressing and Clothing Needs

This section of the chapter outlines and discusses functional needs of adaptive apparel organized by challenges or specialized functions that the user may need to perform daily duties. One example of functional need section includes openings in garments that may aid in donning and/or doffing due to low range of motion of the user. This section contains information as well as dressing challenges and design considerations for:

- low grip strength,

- simple to use,

- extra wide opening,

- easy to reach,

- sensory comfort,

- thermal comfort, and

- ability to hold medical equipment.

Functional need: “Low grip strength”

Disabilities and Clothing needs:

Various disabilities such as cerebral palsy, arthritis, muscular dystrophy, multiple sclerosis, or paralysis affect movement, muscle, and posture. People with those disabilities experience stiff muscles, exaggerated reflexes, lack of balance and muscle coordination, or writhing movements. The physical difficulties eventually impact dexterity associated with smaller movements that occur in the wrists, hands, fingers, feet, and toes. People with low dexterity have difficulty manipulating closures such as zippers or buttons.

Dressing Challenges:

- Decreased muscle strength impacts the ability to manipulate fasteners and closures.

- For example, some Velcro that requires a high level of strength to manipulate, because of their stiffness’s, may not be easy to use for people with low dexterity or older adults who do not have strong grip strength.

Design Considerations:

- The use of a closure should not require much concentration and strength.

- The size and roughness of a closure affect the amount of force required to operate it. If a button or zipper pull tab is small and slippery, it is hard to grasp, hold, and manipulate them for individuals with moderate to severe dexterity difficulty.

- Protrusion, an extension of an object above the surface, also affects the wearer’s ability to manipulate a closure. For example, a ring or piece of fabric attached to a zipper can help users detect and grasp the zipper slider and make zipping/unzipping easier.

Functional Need: “Simple to use”

Disabilities and Clothing needs:

Cognition is holding attention, concentrating, processing information, or communicating and remembering. Autism, dyslexia, dyscalculia, or intellectual disabilities are related to cognition. It is recommended to avoid complex fastening mechanisms that require concentration and greater operating force to make garments as inclusive as possible.

Dressing Challenges:

- For example, hook and eye may require many steps of manipulation and higher levels of concentration. Therefore, manipulating the closure may be challenging for older adults or people with low cognition and dexterity.

Design Considerations:

- One of the principles of Universal Design is simple and intuitive use. The principle suggests that the use of the design should be easy to understand, regardless of the user’s experience, knowledge, language skills, or current concentration level.

- Magnetic zippers require low concentration because the magnets of the closure enable them to automatically match the teeth and help the wearer easily pull up the zipper together.

Functional Need: “Open extra-wide”

Disabilities and Clothing needs:

Many people with physical disabilities experience difficulty dressing. The dressing motion requires a high level of ability to balance, stand, and lift the body parts and extra concentration and effort.

Dressing Challenges:

- People with low mobility or low dexterity can spend a extended period of time to put on and take off clothing due to the need for additional support to stabilize or balance themselves or to use tool(s) to assist in dressing due to standard opening sizes in garments. This extra time spent in challenging dressing situations can lead to personal frustration and physical fatigue.

- Standard garment openings can also be a challenge for caregivers of people with low mobility or low dexterity as they assist the person with dressing. This can involve the caregiver moving limbs of the person or carrying the full weight of the person to put on or take off the garment. This extra physical load that the caregiver provides can be strenuous for them while also potentially putting the person they are providing care to in straining positions.

Design Considerations:

- Using stretch fabrics or elastic band on the entry points (e.g., elastic waistband) can accommodate greater movement flexibility.

- Adding slits or additional closures (e.g., snap closures at both shoulders) to the waist and leg opening can provide greater flexibility for easier body movement.

- Installing a full length of closures (e.g., snaps, Velcro, or zippers) on the side seam(s) can enhance the flexibility of the opening.

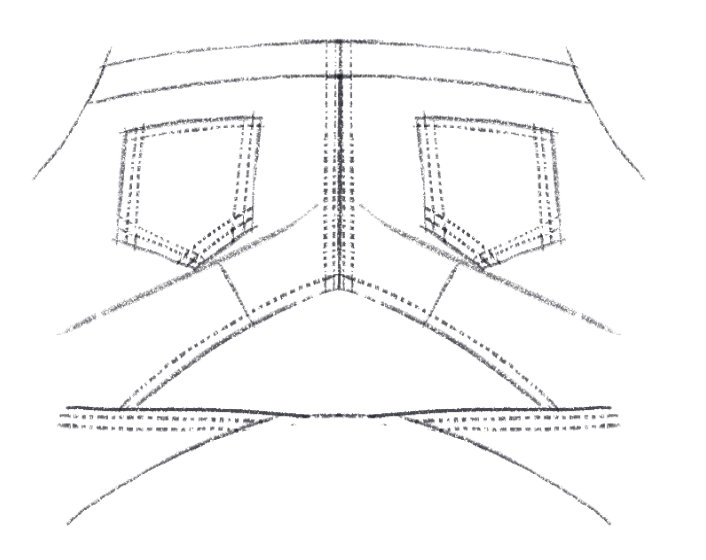

Functional Need: “Easy to reach”

Disabilities and Clothing needs:

People with disabilities such as cerebral palsy, arthritis, muscular dystrophy, and multiple sclerosis have difficulty in mobility due to the decreased ability of body, muscles, and posture movements. Additionally, people with limb differences have limitations on reaching.

Dressing Challenges:

- For example, the zipper located in the left side seam of a skirt may not be reachable to those with a right upper extremity amputation.

- If a pocket is installed at the bottom of a pair of jeans, the design feature may not be easy to use for those experiencing cerebral palsy.

Design Considerations:

- To make wearers easily put on and take off garments, closures should be located along an arc that the hand can reach quickly and without extra exertion.

Functional Need: “Sensory comfort”

Disabilities and Clothing needs:

People who have tactile defensiveness (or sensory sensitivity) are more sensitive to touch than others. Especially, these symptoms may be experienced by adults and children with specific learning difficulties, learning disability, autistic spectrum diagnosis, or other developmental diagnoses. Those individuals may not like the feeling of certain fabrics or texture, tags or seams on clothing, or even wearing socks or shoes.

Dressing Challenges:

- For wheelchair users, back pockets may cause sensory sensitivity because they spend much of the time during a day with a seated position.

- Additionally, back pockets can also lead to pressure sores that can lead to significant health challenges (e.g., hospitalization due to pressure sore infection).

- For adults and children who are neurodivergent, textile selection, construction (e.g., seam type), and labeling of apparel garments can lead to sensory challenges.

Design Considerations:

- When designing apparel products, protrusive elements (e.g., metal clips) or abrasive fabrics need to be avoided.

- For some sensory comfort needs, using compression materials may be desirable.

- Alternative construction/seam and labeling approaches (e.g., flat seams and tagless labels)

- Using stretchable fabric can facilitate ease of movement and wearers may feel more comfortable.

Functional Need: “Thermal protection”

Disabilities and Clothing needs:

Wheelchair users, when the temperature varies during the day, take more time than others to change their clothes or move into a building to maintain their thermal comfort.

Dressing Challenges:

- When there is a dramatic change of temperature, people who have paraplegia or are not able to feel the changing temperature in their body parts, especially lower extremities, cannot feel if they are becoming too cold or hot.

Design Considerations:

- To regulate body temperature by preventing the transfer of heat, apparel products should use some fabric that can quickly react the thermal changes.

- Garments that can be easily worn and removed are useful for those experiencing this challenge but also can properly protect body temperature.

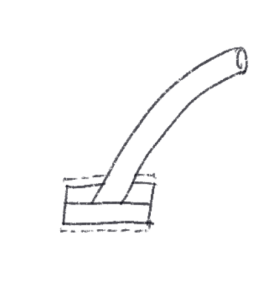

Functional Need: “Ability to hold medical equipment”

Disabilities and Clothing needs:

Some individuals use medical devices and the device’s tube or device itself needs to be associated with their clothing. For one example, Left Ventricular Devices (LVD) are surgically placed into the heart to keep the heart pumping for the individuals who are experiencing heart failure. These devices require that an individual carry a battery pack with them.

Dressing Challenges:

- There are currently apparel products that have been made to hold battery packs (for LVD, and other medical needs that require battery association) but these apparel products are limited in options and can be expensive.

- Additionally, proper garment that can be associated with the devices/or tubes is also limited.

Design Considerations:

- Adding pockets (e.g., in-seam pockets) and make a couple of holes on the existing garments can easily solve this problem.

This content was provided by Morgan Tweed, CPACC. Morgan is an Accessibility Specialist in Architecture and Landscape Architecture. Morgan has participated as a client in apparel design class projects focusing on adaptive apparel.

General Advice for Design

People with disabilities have lives, events, and jobs. They don’t want to look bad. Most clothing for people with disabilities tends to look like night clothes or hospital wear. Adaption doesn’t have to look frumpy! Don’t fall into that lazy trap.

Ask if they want to take visual attention away from their disability, highlight it, or ignore it as a factor. Some people want to be seen separately from their disability; some choose to embrace it. You don’t want to make assumptions here.

Ask if they consider something an asset or an inconvenience. Example: A large-chested person may not want a push up bra.

Specific Advice for Design by Disability

There are many different design adaptions that may help depending on the situation. Below are some of the major adaptations that should be considered. Keep in mind that this is not an exhaustive list by any means, and everyone may have different needs. There are many other things to consider, but this gives you a good layout of some of the main things to watch out for.

| Disability | Advice for consumer-friendly design |

| Vision differences |

|

| Deafness and Hard of Hearing |

|

| Sensitive skin and skin conditions

|

|

| Neurodivergent |

|

| Wheelchair users |

|

| Other mobility aids and mobility needs |

|

| For size differences |

|

| For weight differences |

|

| For unique shapes |

|

| For swelling |

|

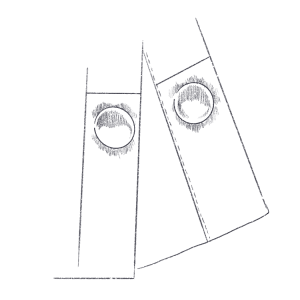

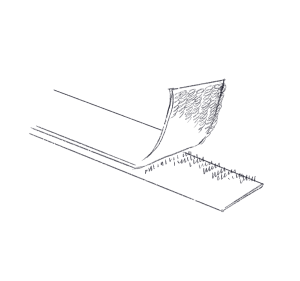

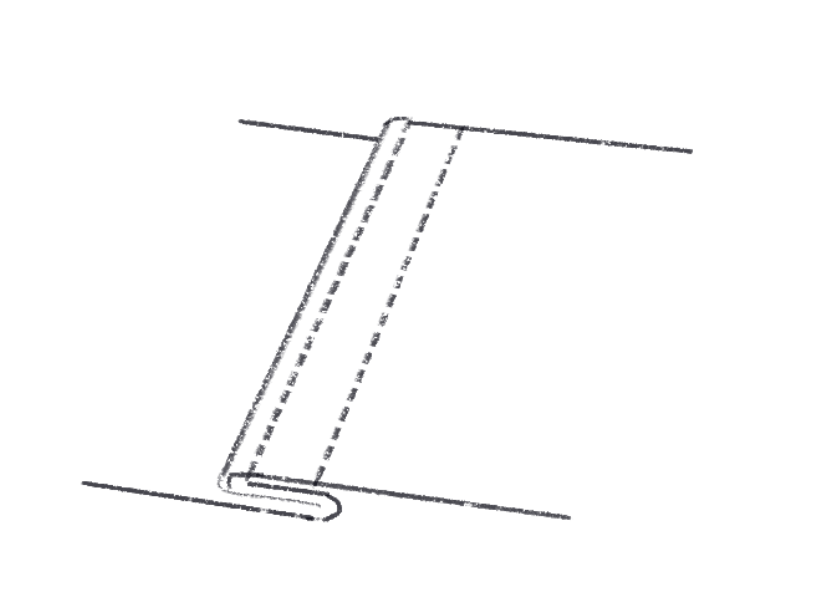

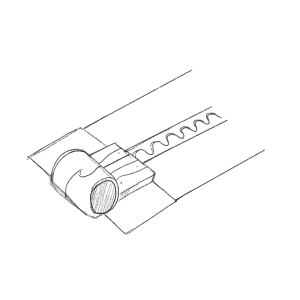

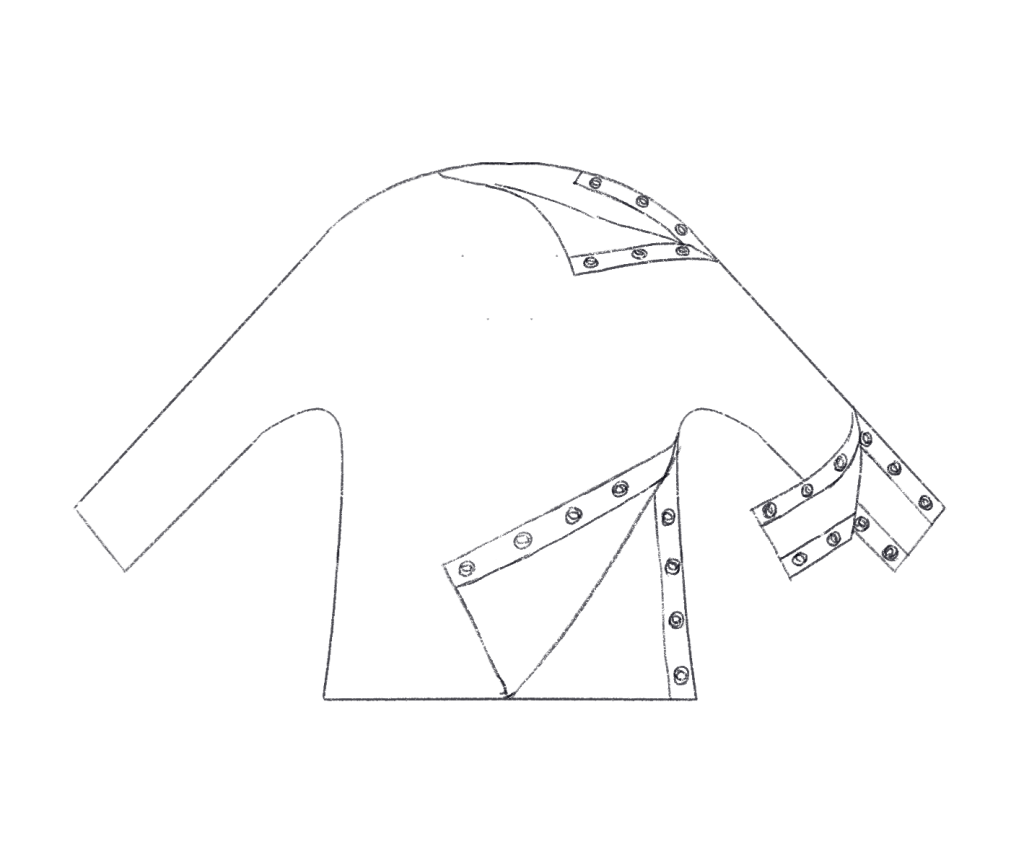

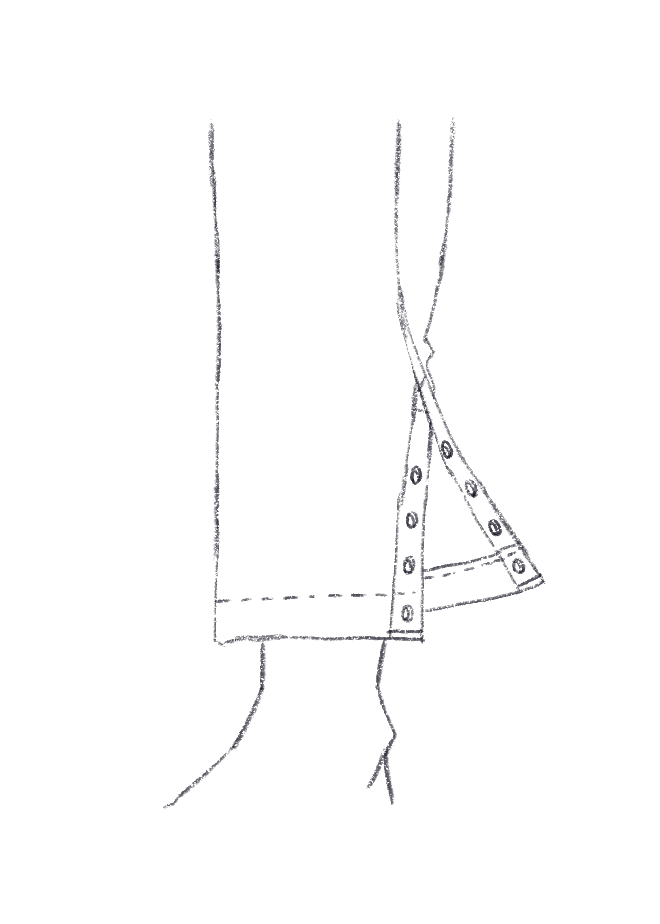

Illustrated Glossary of Clothing Adaptations Organized by Wearer’s Needs

In the illustrated glossary of clothing adaptations section, figures have been created to help visually communicate apparel components or notions that can be considered in the apparel design process to address functional needs for adaptive users. These visuals are organized following the same structure as above a) low grip strength, b) simple to use, c) extra wide opening, d) easy to reach, e) sensory comfort, f) thermal comfort, and g) ability to hold medical equipment.

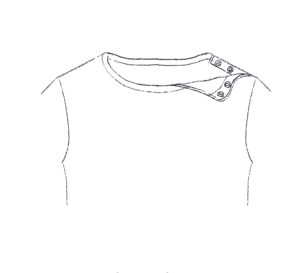

Low grip strength

Simple to use

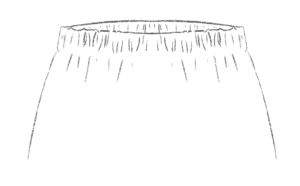

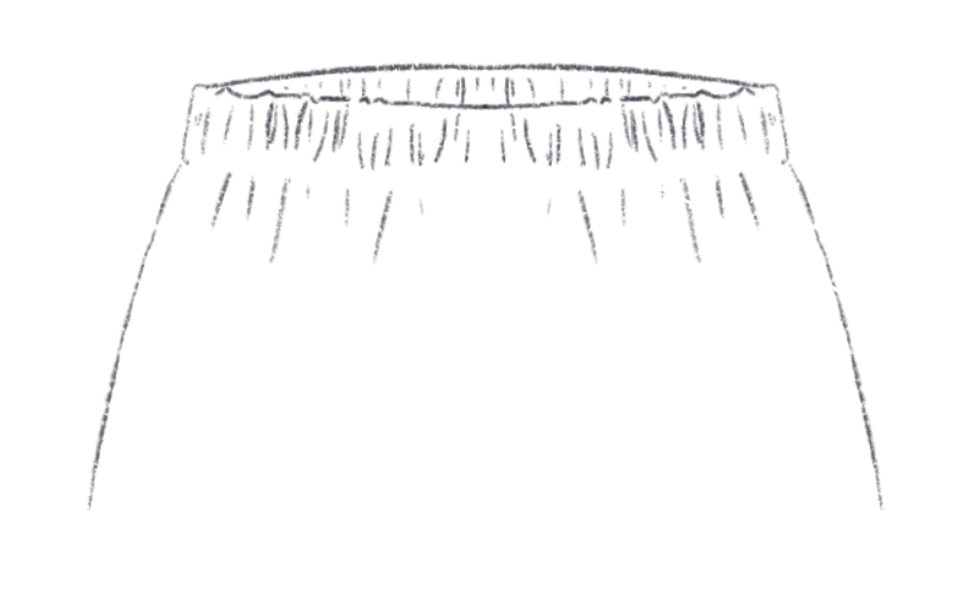

Open extra-wide

Ease of movement (lower body) – bend, squat, climb, etc.

Sensory comfort

Thermal protection

Ability to hold medical equipment

Client communication guide, including use of person-first language

Language around adaptive apparel is something to be mindful of to show consideration to the person who has a disability. This section of the chapter discusses use of person-first language as well as a guides for interviewing persons with a disability.

People first language is used to speak appropriately and respectfully about an individual with a disability. People first language emphasizes the person first not the disability. For example, when referring to a person with a disability, refer to the person first by using phrases such as: “a person who …”, “a person with …” or, “person who has…” Below are suggestions on how to communicate with and about people with disabilities. Additional online resources are available through the National Institution of Health.

| People First Language | Language to Avoid |

| A person with a disability | The disabled, handicapped |

| A person without a disability | Normal (referring to a person without a disability as normal insinuates that persons with disabilities are not normal) person, a healthy person |

| A person who uses a wheelchair | Confined or restricted to a wheelchair, wheelchair-bound |

| A person with a physical disability | Crippled, lame, deformed, invalid, spastic |

| A person with cerebral palsy | CP diagnosis |

General information about interviewing clients for adaptive apparel design

Interviews with clients with disabilities can expand a designer’s knowledge of the environmental factors that affect the use of apparel products. Through the direct communication with interviewees, designers can gain a wealth of information of the problems involved. Defining the problems, as the first phase of the design process, can create an understanding of all the information acquired through research. This is one of the most critical tasks of designing.

According to Watkins and Dunne (2015), three important factors need to be clarified in order to define a functional apparel design problem:

- Who are the users?

- What is the activity?

- What are the environmental conditions under which apparel will be used?

Then, specific goals for the apparel being developed (e.g., thermal protection, mobility) are stated and determined.

Novice interviewers often lead interviewees and thus prejudice their responses. What people do and what they say they do are often at odds; therefore, interviews may not provide accurate information. Designers need to be more professional, get trained for interviewing, and become familiar with appropriate interview techniques.

Specific information about interviewing clients with disabilities

- Use people-first language (e.g., “an individual with a disability” compared to “a disabled individual”).

- Speak normally, without patronizing the person.

- Disabilities can affect people in different ways, even when one person has the same type of disability as another person.

- Some disabilities may be hidden or not easy to see.

- Don’t make assumptions regarding someone’s capabilities or attitude toward their disability.

- Ask before you help.

- You may always ask a person how they would like you to refer to their disability.

- Wheelchairs, walkers, and crutches are mobility aids. Without the use of these mobility aids the person may be restricted from participation in their community.

- Assistive technology is a product or equipment used to increase, maintain, or improve a person’s functional capabilities.

- Many blind, deaf, or persons who are hard of hearing consider the words “visually impaired” or “hearing impaired” to be offensive. Blind means without the sense or use of sight. Deaf means unable to hear. They do not wish to be identified as diminished in strength or value as the word “impaired” denotes.

This content was provided by Morgan Tweed, CPACC. Morgan is an Accessibility Specialist in Architecture and Landscape Architecture. Morgan has participated as a client in apparel design class projects focusing on adaptive apparel.

The following should be considered prior to any working session with the client, such as an interview, design session, or fitting.

Before the Meeting:

You should find out about their needs while you are working with them. The person that you are fitting might have never been in a clothing fitting situation before or have had clothes designed for them. Let them know what your usual process is then ask them what about that they might need changed.

- If they need to bring help them to maneuver and get around, this should be set up ahead of time.

- If they have parts of their body that they do not want exposed, set up expectations for what you need to access. They can wear more form fitting clothing or avoid certain areas.

A huge portion of adaption is respecting the time. Most disabilities take up time and effort. They must be scheduled around. Since, sometimes fitting and design sessions can take a bit of time, it is helpful to warn them of this additional time need in advance. This is very useful for:

- People that have neurodivergences know what to expect.

- People with timed medicines know if they need to bring medicines with them.

- People who have timed food, like those with blood sugar concerns or eating disorders.

- People that are dependent on others for travel.

The Meeting Space:

You want to make sure that they can get there and be comfortable in the space, so these are important things to consider:

- Is there accessible parking or public transit access?

- Is the path to get to the space is accessible to people who use wheelchairs and crutches?

- Are there tactile paths on the concrete?

- Is there is an accessible entrance with smooth paths, gentle slopes/ramps?

- Is there wayfinding?

- Are there signs with braille or high contrast?

- Are there automatic or button operated doors? If not, are they hard to open? You may need to go open them for your client.

- Are the doorways that they must go through are wide enough? (32” is standard) Do the doors have high thresholds?

- Is the room large enough for a shopping cart to be turned around? This is a good way to visualize if someone can get a larger wheelchair in.

- Are there accessible bathrooms?

General Advice for Consumer Research Interviews:

Working with people in the disabled community, no matter what the field, is about respect, information, and adapting. No two people with disabilities are going to be the same. Even people with similar disability types might have different needs. So, before you get anything started, right off the bat, ask them what adaptions they’ll need. But you can’t put it all on them either. Prior to the interview conduct background consumer research of user needs. Conduct market analysis and materials research to understand currently available designs and materials. This will give you some items to discuss with your client and understand how they evaluate these potential solutions.

Don’t use what you’ve learned from other disabled people you have met or designed for to claim you know what they need. It is never a good idea and feels dismissive. No two experiences are the same. Also don’t assume a temporary experience like having a broken leg is the same.

Listen to them. If they aren’t comfortable with the design or method, change it.

Specific Advice for Adaptations to Consumer Research Interviews by Disability

Once they are there and ready, there are many different adaptions that may help depending on the situation. Here are some of the major adaptations that should be considered. Keep in mind that this is not an exhaustive list by any means, and everyone may have different needs.

| Disability | Advice for Direct Consumer Research |

| Vision differences |

|

| Deafness and Hard of Hearing

|

|

| Sensitive skin and skin conditions

|

|

| Neurodivergent

|

|

| Wheelchair users |

|

| Other mobility aids |

|

| For weight differences |

|

| For unique shapes |

|

| For swelling

|

|

Remember: If in doubt, ask, be respectful, be patient, and design for disabled people, not around disabled people.

Materials Research: Textiles (Selection and Rationale)

In this section of the chapter, textiles (fabrics) are reviewed for considerations regarding selecting materials for adaptive apparel design. Additionally, resources for more in-depth information on textile performance and textile science are provided. A brief overview of the importance of selecting the right textile for worn products

Selecting proper textiles for designing apparel products considering people with disabilities is critical. The target consumer’s lifestyle needs to be considered to understand how a garment will be used and laundered and its expected level of wear and tear. Especially, those people are often more sensitive to feel fabrics, especially those who have tactile defensiveness.

Textiles for adaptive apparel

Thermal protection

One of the primary functions of textiles is to insulate the body to prevent transfer of heat. Improving the thermal protection of apparel products by adding layers or use fabrics of thermal resistance is essential. Concerning the thermal issues, people with disabilities, for example, wheelchair users might have some limitations in choosing outwear apparel because they sit in a wheelchair, and it is difficult to react the climate change. A combination of textile layers and the air gap prevents thermal energy transfer to the skin.

Comfort

The flexible nature of textiles is of great importance to apparel which needs to move with the human body. The need for increased ease through the armhole area and cross back to enhance comfort and mobility relative to the donning and doffing process is identified as another priority for people with disabilities. Easily stretchable/flexible or knitted fabrics are favored because stiff materials make donning and doffing difficult.

Easy care

Daily clothing tasks such as laundering, ironing, or storing garments is important for everyone. However, those are challenging for people with disabilities because of their physical difficulties. Some adaptive apparel brands use stain-, water-, or wrinkle-resistant fabrics, making it easy to care for the products.

Breathability

Fabric breathability is the ability to remove moisture created during perspiration (one of the most common problems), which implies optimal moisture absorption and air circulation. This fabric characteristic is critical for those who have disabilities and have difficulties changing their garments frequently or are vulnerable to heat or climate changes.

- Complete Textile Glossary (https://www.fashiontrendsetter.com/downloads/Fiber_Dictionary.pdf): This PDF glossary by Celanese Acetate LLC is over 200 pages and offers detailed definitions for fibers and fiber-related processes as well as black and white illustrations.

- Cotton Works (https://www.cottonworks.com/en/): The Cotton Works program is an industry resource for a professional or emerging professional in the apparel and textile industry. Develop expertise for every stage of product development and marketing by diving into our comprehensive resource with data and research, market and trend analysis, timely webinars, and informative videos.

- Fabric Link, Fabric University, Course Curriculum (https://www.fabriclink.com/university/index.cfm): This site provides general information about fibers including a brief fiber history page, fiber producers and trademarks, characteristics of textile fibers, a dictionary of fabric terms, fabric care tips, fiber identification through burn test instructions and consumer alert/fabric recalls. It also provides brief descriptions of 150 high-performance products listed alphabetically.

- FIT Gladys Marcus Library – textiles (https://fitnyc.libguides.com/periodicals-by-subject/textiles): Fashion Institute of Technology Library provides an organized list of periodicals, textbooks, or resources related to textile and design.

- Textile Hive (https://www.textilehive.com/): This site provides an online textile collective and archive.

Assembling Research

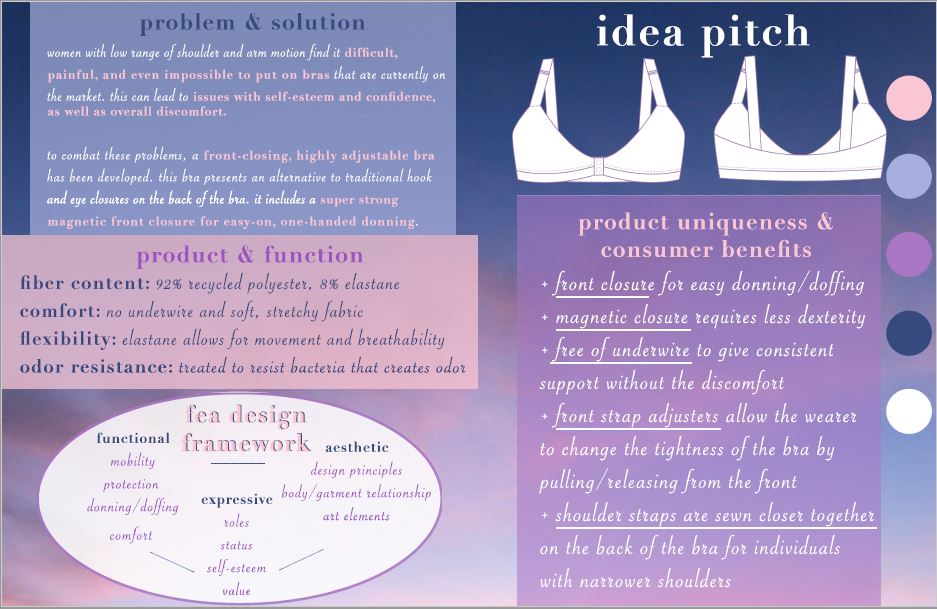

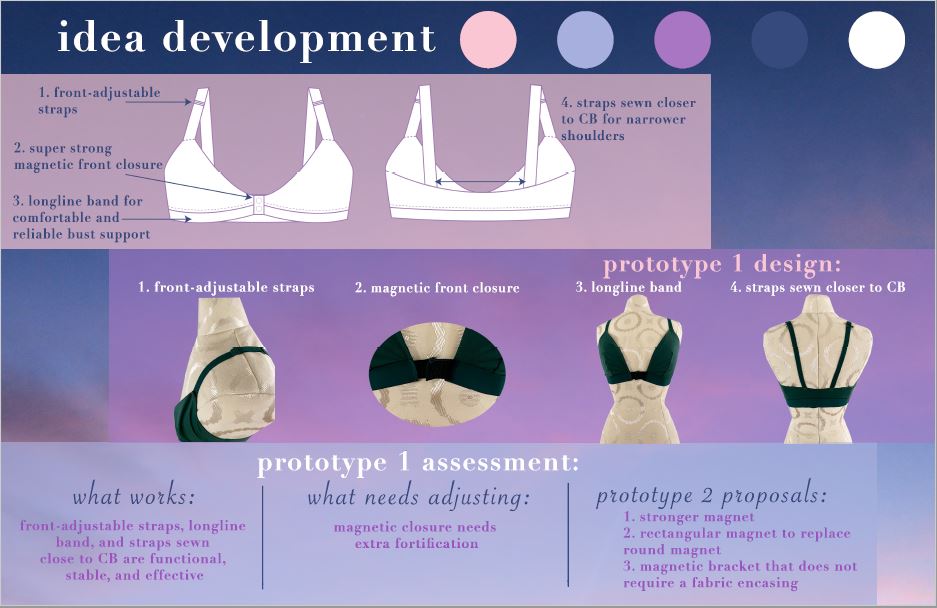

Once the designer has collected all the relevant research to inform future stages of the design process, they may find it helpful to assemble data into visuals to help them to not only remain focused during their ideation phase, but also to communicate their design justifications to other/stakeholders. Visuals can take on different forms, such as tables, charts, word clouds, technical drawings with call outs, or other dynamic graphics, or a combination of multiple visuals. Materials and visuals may be more informal, such as in a sketchbook, or more formal, such as a presentation board. Below are two visuals (presentation boards) that communicate design research conducted and how it informed the design ideation process and sample-making phase for an adaptive apparel design.

You can access a long image description for the visual above in the footnotes of this page.[1]

You can access a long image description for the visual above in the footnotes of this page.[2]

References

McBee-Black, K. (2022). “Making Life Easier”: A Case Study Exploring the Development of Adaptive Apparel Design Innovations from a User-Centered Approach. Fashion Practice, 14(2), 203–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/17569370.2022.2031011

McBee-Black, K. (2021). The Role of an Advocate in Innovating the Adaptive Apparel Market: A Case Study. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal, 0887302X211034745.

Kosinski, K., Orzada, B., & Kim, H.-S. (2018). Commercialization of Adaptive Clothing: Toward a Movement of Inclusive Design. International Textile and Apparel Association Annual Conference Proceedings. https://www.iastatedigitalpress.com/itaa/article/id/1208/

Farha, L. (2021). Identifying the gap between adaptive clothing consumers and brands. University of Delaware. See p. 5 (adaptive clothing brands for kids)

Na, H.-S. (2007). Adaptive Clothing Designs for the Individuals with Special Needs. In Journal of the Korean Society of Clothing and Textiles (Vol. 31, Issue 6, pp. 933–941). https://doi.org/10.5850/jksct.2007.31.6.933

Casey, C. (2020, March 19). Do your D&I efforts include people with disabilities? Harvard Business Review. Retrieved from https://hbr.org/2020/03/do-your-di-efforts-include-people-with-disabilities

Bhattarai, A. (2021). No seams, buttons or tags: Retailers are rethinking back-to-school clothing for students with disabilities. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2021/08/06/adaptive-clothing-target-kohlsjcpenney/

Webb, B. (2022, July 13). The Farfetch of adaptive fashion? High-end marketplace Adaptista’s big ambitions. Vogue. Retrieved from https://www.voguebusiness.com/fashion/the-farfetch-of-adaptive-fashion-high-end-marketplace-adaptistas-big-ambitions

Feedback Survey

Feedback Survey

We welcome your feedback as a user of this OER or potential collaborator on Adaptive Apparel Design work. Please click on this survey link or use your personal device to scan the QR code that will then link you to the online survey.

- An infographic with the title: "Idea pitch." Four major sections are presented: Problem and solution, product and function, fea design framework, and product uniqueness and consumer benefits. Problem and solution section: Women with low range of shoulder and arm motion find it difficult, painful, and even impossible to put on bras that are currently on the market. This can lead to issues with self-esteem and confidence, as well as overall discomfort. To combat these problems, a front-closing, highly adjustable bra has been developed. This bra presents and alternative to traditional hook and eye closures on the back of the bra. It includes a super strong magnetic front closure for easy-on, one-handed donning. Product and function section: Fiber content: 92% recycled polyester, 8% elastane. Comfort: no underwire and soft, stretchy fabric. Flexibility: elastane allows for movement and breathability. Odor resistance: treated to resist bacteria that creates odor. FEA design framework section: Functional: mobility, protection, donning/doffing, and comfort. Expressive: roles, status, self-esteem, and value. Aesthetic: design principles, body/garment relationship, and art elements. Product uniqueness and consumer elements section: Front closure for easy donning/doffing; magnetic closure requires less dexterity; free of underwire to give consistent support without the discomfort; front strap adjusters allow the wearer to change the tightness of the bra by pulling/releasing from the front; shoulder straps are sewn closer together on the back of the bra for individuals with narrower shoulders. ↵

- An infographic with the title: "Idea development." Three major sections are presented: a technical flat of the proposed design, photos of the prototype design, and an assessment of the prototype. The technical flat design has 4 callouts: 1. front-adjustable straps, 2. super strong magnetic front closure, 3. longline band for comfortable and reliable support, 4. straps sewn closer to CB for narrower shoulders. The prototype design section showcases photos of the mockup, a simple black bra containing the elements mentioned in the first section. The prototype assessment section reviews what works, what needs adjusting, and proposals for a second prototype. What works: front-adjustable straps, longline band, and straps sewn close to CB are functional, stable, and effective. What needs adjusting: magnetic closure needs extra fortification. Prototype 2 proposals: a stronger magnet, a rectangular magnet to replace the round magnet, and a magnetic bracket that does not require a fabric encasing. ↵

an assessment of the potential market for your work, including the consumer base, competing businesses, and overarching landscape surrounding your product or service.

a type of market analysis which focuses on the base of potential customers for your product or service.

the assessment and identification of materials relevant to a business' apparel design.