2 2.10 Moves for Evaluating Scholarly Information

Evaluating scholarly information takes more than just verifying that it has been peer reviewed, and then reading the title and abstract. Reading and evaluating a scholarly source can help determine if it is accurate, reliable, and relevant. In addition to using SIFT, there are some other strategies and considerations that can be useful when evaluating scholarly information.

Review the source

When reviewing scholarly resources, start by investigating the publisher or publication venue. Their reputations can tell you a lot about whether you should trust what you find there. A warning sign could be if several sources call the journal or publisher “predatory,” which often means that articles or books are published with no review and at great cost to the author.

For journal articles, start by investigating the journal. Google and Wikipedia can usually help you find more information. Look for the journal’s website to find its editorial policies, which will tell you whether the articles in that journal are peer reviewed. If you’re unsure after that, then dig in to investigate the publisher of the journal. Positive things to look for include whether the journal is affiliated with or published by a well-known scholarly or professional society or a respected university. When you’re unsure whether or not your source is something you should use, contact your librarian.

For books, go straight to investigating the publisher to learn more about their reputation. As with journals, when a book’s publisher is associated with a university or scholarly society, it’s usually a sign that the contents are trustworthy. Some scholarly books contain chapters written by multiple authors, compiled by an editor. Be careful not to assume that the editor on the cover of the book is the author of the individual chapters. Make sure to check the credentials of the author of the specific chapter you want to use, rather than trusting that each chapter is credible just because of who the editor is.

In the end, the usefulness of a scholarly resource will depend on two things: if the source is authoritative and if its content meets your needs.

Consider its timeliness

When evaluating a source to include in a paper or project, you also need to consider when your source was published. Depending on your topic or assignment, you may need something published within the last five or ten years, as can be the case when researching recent events or medical information. If you’re researching the public’s reaction to a historical event, it may be necessary to consult an older source. Consider the requirements of your assignment. Does timeliness or currency matter for this topic? If you’re not sure, ask your instructor. Also think about when the theory or idea was first introduced. If it has been around for a long time, it has had more opportunity to be criticized, overturned, built upon, or reinforced.

Review its methods

If the source has an abstract and conclusion, read those first to get an idea of what the authors are trying to say. Then dig into the methods section to see how the authors came to those conclusions. Be on alert for things like methods that are not explained (e.g., only stating “We ran a qualitative analysis”) or that you don’t understand and may need to look up. Reviewing a paper’s methods can give you a deeper understanding of how the authors got their results and will put their findings into a better context.

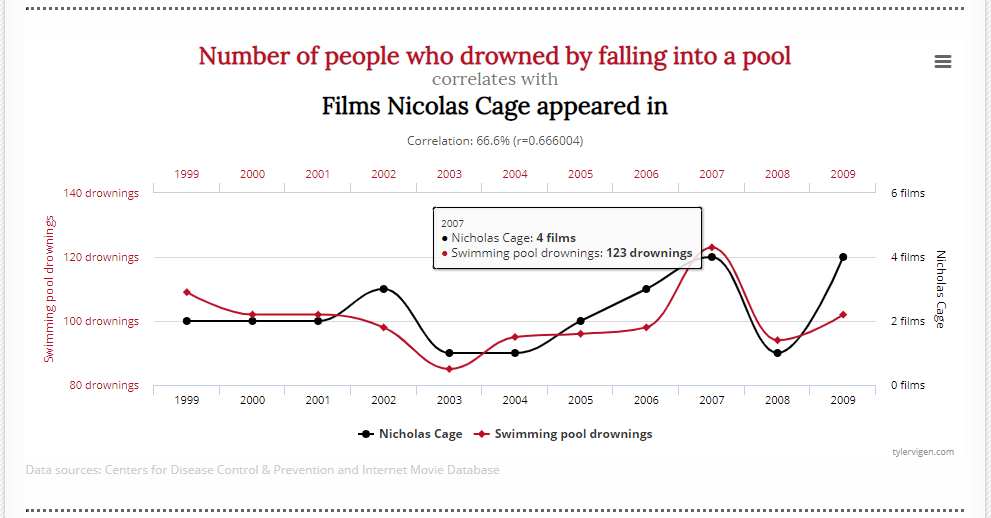

Understand the graphics

Examine the graphics being presented in your source to understand how they relate to the data. Consider whether results are being accurately represented. One thing to watch out for is if only a subset of data is shown in a graphic. For example, a graph may exclude data that doesn’t reinforce the author’s conclusions.[1] This can impact your understanding of the results.

Correlation does not equal causation

Even when all the data is displayed in the graphic, there might be conclusions drawn from it that don’t make sense. Trends can seem to form patterns or overlap (correlation) without actually being related in any way. Good research tests whether there is truly a connection where one change causes another (causation).

Is Nicolas Cage’s presence in movies really impacting the number of swimming pool drownings? Is the number of pool drownings impacting the number of Nicolas Cage movies made per year? No! These two variables were chosen because they line up, not because there is actually any connection between them. Remember this when you’re looking at scholarly graphics, as well — though they may not be nearly as entertaining.

- Calling Bullshit by Carl Bergstrom and Jevin West https://callingbullshit.org/tools/tools_misleading_axes.html ↵