1.7 The Flow of Information

A factor you may not have considered when starting your research is time. It’s important to know when something happened because that can help you determine both how much and what type of information might exist on your topic. The closer you are to the actual date something happened, the less information there is likely to be on that topic. By the same token, the further away you are from the event in time, the more likely it is that more information and publications may be available. This concept is called the flow of information.

Primary Sources

The first information available about a particular happening usually attempts to describe or report the event on the same day or very soon after it happens. These types of information sources are often called primary sources because they are the first accounts and often provide eye-witness perspectives. (Note that some disciplines in the sciences define primary sources as publications describing original research.)

Common types of primary sources include web and newspaper articles from the time of the event, diaries, news transcripts, photographs, and citizen videos.

Here’s an example:

On June 12, 2009, election protests began in Iran. Worldwide observers noted that the protesters made extensive use of Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube to communicate what was happening.

On June 12, 2009, election protests began in Iran. Worldwide observers noted that the protesters made extensive use of Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube to communicate what was happening.

Television news coverage of the events began at once.

On June 14, 2009, an entry on the protests was created by anonymous users in Wikipedia.

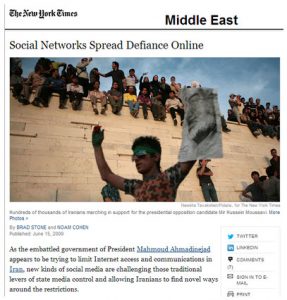

The New York Times newspaper published an article and photo on the topic on June 15, 2009.

On Twitter, thousands of #IranElection tweets documented the developing situation. All of these are examples of primary source, produced while the protests were actually occurring.

In general, you can expect to find information on the web, television news, and social media in the first few days after a newsworthy event. As weeks go by, other information sources begin to emerge, adding new perspectives and information on the topic. Articles in news magazines and popular consumer magazines (such as Time, The New Yorker, Newsweek, People Magazine, Smithsonian, The Economist, etc.) – the types of magazines you can easily find in supermarkets, superstores like Walmart and Target, and most bookstores – appear next.

In our example, on July 27, 2009, Newsweek published a short article on the election protests and media use in Iran; The Economist and other popular consumer magazines also began publishing short articles and opinion pieces around this time. So, additional sources of information started being published months later, joining the mix of primary sources discussed earlier.

Secondary Sources

As more time passes, more information and scholarly research on noteworthy events becomes available. Often the focus of this new material is to understand or analyze the event, or to put it in context historically, by comparing it to other issues, trends, or movements.

These types of analytical, after the fact, information sources are called secondary sources. These typically look back in time and analyze the original event in much greater depth and context. Common types of secondary sources include books, research articles, and encyclopedia articles. (Some disciplines may define secondary sources mostly as books and encyclopedia articles.)

Let’s return to the example of the 2009 election protests in Iran.

In 2010, one of the first peer-reviewed journal articles on the topic appeared in the International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Society (iJETS). Many other peer-reviewed journals published research articles on the topic from 2012 to the present. Also in 2010, scholarly book chapters began to be published on the protests, and in 2011, brief mentions of the event began to appear in some encyclopedias (such as Encyclopedia of Social Movement Media).