Introduction

English Language Learners and Emergent Bilinguals

Ji-Yeong I and Ricardo Martinez

Determine if each of the following statements are True or False. Make sure you answer all four questions.

Did you find the True or False statements interesting? Now we will ask you to brainstorm the following questions to get ready to read this chapter:[1]

BUMBLEBEE Pre-reading Questions

(Building Understanding in Mathematics By Leveraging Emergent Bilinguals’ as Equals in Education)

- How do you define English language learners?

- How does your school or district define/identify English language learners?

- What challenges and obstacles do you think English language learners encounter in an English-only school and how do you think it impacts their lives? What do you think causes those challenges?

Why ELLs?

English language learners (ELLs)—the students whose fluent languages do not include English—often face multiple academic learning challenges when English is the only instructional language in their schools or when their school has no support for their native language.

The issues surrounding ELLs are complicated and have multiple layers. It is not only about language. The naïve belief—obtaining English proficiency will resolve ELLs’ educational issues—may lead to naïve teaching approaches for ELLs, such as providing simple translation or holding grade-level curricula until they master English. The misguided approach for teaching ELLs may result in the continuous gap of the mean scores in nation-wide mathematics assessments (NAEP, 2013, 2015, 2017) between ELLs and non-ELLs.

Our first step to unravel the complicated issue is to understand who ELLs are.

Who Are ELLs?

It is difficult to define ELLs because the existing definitions of ELLs vary by states, districts, and schools. The inconsistency increases when we add the different assessment tools used to identify ELLs and the variations in the identification of ELLs.

“A prerequisite for understanding English learners is a systematic analysis of their demographic characteristics and of whether and how these characteristics differ from those of their non-EL peers. These are NOT simple matters.” (NASEM, 2017, p. 63)

The US Department of Education provides this interactive online document to explain the characteristics of ELL students. While keeping in mind that the dataset includes many limits, which are addressed in the document. Explore the information contained in the Our Nation’s English Learners.

If you like to learn more about the demographics of ELLs, refer to this recent document, Promoting the Educational Success of Children and Youth Learning English (NASEM, 2017), especially Chapter 3, “The Demography of the English Learner Population.”

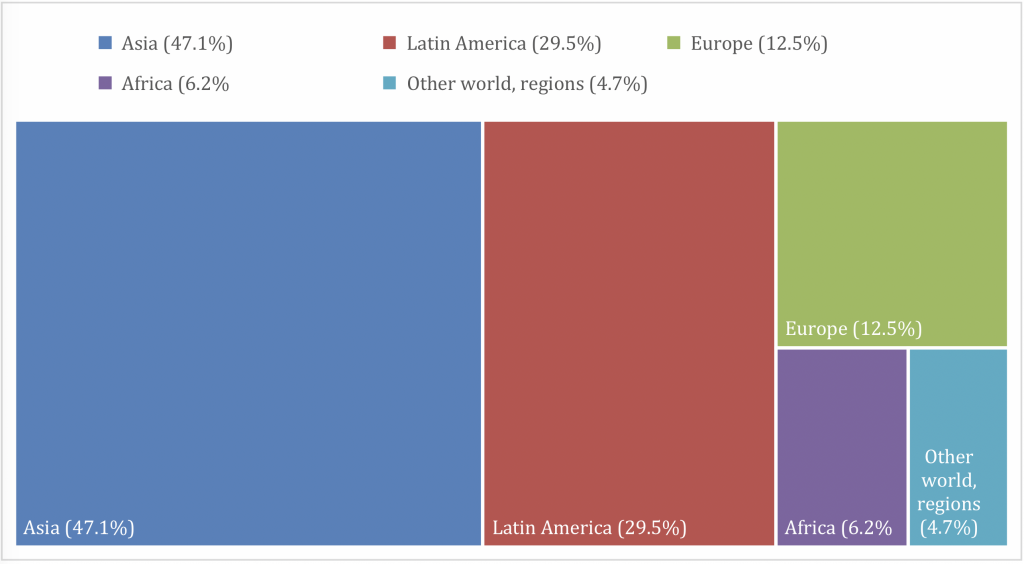

We will share some interesting facts from this document. The figure below shows where the new immigrants originally came. While mass media have focused on immigrants from Latin America, the largest group of recent immigrants are from Asian countries (approximately 50% as Figure 1 shows). Asian Americans are now the fastest-growing, highest-income, and best-educated racial/ethnic group in the U.S. (Pew Research Center, 2012).

It is well known that the majority of ELLs in the US are US-born. However, the distributions vary along with age. It is important to note the following two implications from NASEM (2017).

- Not all high school foreign-born ELLs are newcomers. Foreign-born ELLs arrive in the U.S. at a younger average age (4.97 years) relative to foreign-born non-ELs (7.6 years), but their ELL status stays until they are in high school. This implies “foreign-born ELs appear to find themselves in disadvantaged structural contexts that limit their access to services needed to improve their English proficiency” (p. 74).

- The US-born ELLs are almost 50% of the ELL population at age 18. For 18 years, they do not receive enough opportunities to access to achieve English proficiency (and/or academic success) in the current US school structure).

The NASEM (2017) Chapter 3 summarizes three core facts of the ELL populations (p. 98), which are shared here.

- The cultures, languages, and experiences of English learners are highly diverse and constitute assets for their development, as well as for the nation.

- Many English learners grow up in contexts that expose them to a number of risk factors (e.g., low levels of parental education, low family income, refugee status, homelessness) that can have a negative impact on their school success, especially when these disadvantages are concentrated.

- As the population of English learners continues to diversify, limitations of current data sources compromise the capacity to provide a more comprehensive description of the population’s characteristics for policy makers, administrators, and teachers who have responsibilities for their education.

Why Emergent Bilinguals?

You must notice various terms are used for ELLs: LEP, English learner (ELs), ESL, ELD, etc. We need to choose one term to have clear conversations throughout this book. So, let’s begin with the story behind these names.

Before 2015, the USA federal government officially used “Limited English Proficient (LEP)” to call individuals who do not speak English as their primary language and who have a limited ability to read, speak, write, or understand English. No Child Left Behind (NCLB) had described these students as those “whose difficulties in speaking, reading, writing, or understanding the English language may be sufficient to deny the individual the ability to meet the State’s proficient level of achievement on State assessments” (2001). The official definition in Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) is of students “ages 3–21, enrolled in elementary or secondary education, born outside of the United States or speaking a language other than English in their homes, and not having sufficient mastery of English to meet state standards and excel in an English-language classroom” (Title III, Elementary and Secondary Education Act [ESEA], as cited in National 23 Research Council, 2011, p. 5). In 2015, ESSA simply called these students English Learners (ELs). Still, ELL or EL is a common term used in many states, including Iowa.

Recently, researchers (e.g., Ofelia García) have challenged these labels by suggesting to transform our view towards these culturally and linguistically diverse students. Let’s check the following facts first.

- As García noted (2006a), ELLs are “only the tail of the elephant,” 2.7 million of the 10.9 million bilingual and multilingual children in the U.S.

- “By focusing only on the elephant’s tail, or those students who are not proficient in English, we lose sight of the incredible potential of the millions of bilingual and multilingual children in this country who can become national resources in building a peaceful coexistence within a global society and helping the United States remain economically viable in an increasingly multilingual world.” (García & Kleifgen, 2010, pp. 10-11)

When we use ELLs and ELs, we easily forget or neglect the fact that they are bilingual (or even multilingual). Emergent Bilinguals are suggested since these students are becoming bilinguals. The word “bilingual/multilingual” implies a positive and intellectual asset. While the terms LEP/ELL/EL focus on what the students cannot do, this term Emergent Bilingual focuses on what they can do even before they become fluent in English.

Here is the reason that García and Kleifgen (2018) prefer to use Emergent Bilingual in their book Educating emergent bilinguals: Policies, programs, and practices for English learners.

State and local educational authorities prefer the term English language learner (ELL) or English learner (EL) because these are protected labels. That is, once students are given this label, their English learning needs are recognized and funds are allotted to their education. But the ELL/EL label has serious limitations: It devalues other languages and puts the English language in a sole position of legitimacy. It also focuses solely on the development of what is referred to as “academic English,” ignoring other parts of students’ language and education.

We prefer, and use here, the term emergent bilingual because it has become obvious to us that much educational inequity is derived from obfuscating the fact that a meaningful education will not only turn these English learners into English proficient students but more significantly, into bilingual and multilingual students and adults. Emergent bilingual most accurately indexes the type of student who is the object of our attention–– those whose bilingualism is still emerging. (p. 27)

We also prefer to use Emergent Bilingual who will be Proficient Bilingual sooner or later. Here we use “bilingual” as an inclusive term that includes multilingual who can use more than two languages. With using Emergent Bilingual, we (teachers, parents, policymakers, educators, and people) can pursue different educational goals. Rather than merely learning English and becoming a fluent English speaker, our educational goal for Emergent Bilinguals is to support them to be Proficient Bilinguals and successful academic learners by providing them with a high-quality curriculum because they have the potential to accomplish by using both languages.

Here’s one more emphasis on using Emergent Bilinguals, which is related to Chapter 7.

Giving emergent bilinguals a name that does not focus on their limitations means that their family and community language practices are seen as an educational resource. Instead of assigning blame to parents and community for language practices that may not include English, the school can begin to see the parents and community as the experts in the students’ linguistic and cultural practices, which are the basis of all learning. As a result, family and community members will be able to participate in the education of their students from a position of strength, not from a position of limitations. (García & Kleifgen, 2018, p.28)

We used ELLs in the beginning because ELL is the official term in many states and we want to avoid any possible confusion of using other terms. After this point, we will use Emergent Bilinguals in this book. We may sometimes use ELL or EL for a specific reason in our context, but we want to make it clear that Emergent Bilingual is the main term we use for this book.

Why don’t you go back to the beginning of this chapter and try the True or False activity? With the knowledge you obtained from reading this chapter, you may have a different result.

Overview of the Book

This book consists of three parts. The goal of the first part is building fundamental knowledge such as defining terms, exploring how theoretical backgrounds evolved, and the main framework. In this introduction, we provide the definition of English language learners and introduce Emergent Bilinguals as a shared language that will be used in the entire book.

Chapter 1 describes the multiple challenges Emergent Bilinguals generally experience in mathematics classrooms. Through the challenges, we can see that mathematics is built on a certain culture and language system and how teaching and learning mathematics is related to language. When we accept the political and cultural nature of mathematics and understand the role of language in learning mathematics, we can recognize why Emergent Bilingual students struggle in mathematics classrooms. The dual challenges of learning mathematics and English is not the only barrier Emergent Bilinguals experience in school. The pervasive deficit view towards Emergent Bilinguals may seriously influence their learning.

Chapter 2 points out this issue and explores culturally sustaining pedagogy, which is a core lens of this book. From the theoretical background of culturally sustaining pedagogy to culturally responsive mathematics teaching lesson analysis tool, this chapter aims to shine the intersection of culturally sustaining pedagogy, Emergent Bilinguals, and mathematics.

The second part of the book focuses on teaching practices designed for Emergent Bilinguals in mathematics classrooms. Chapter 3 is all about teaching strategies. We try to make connections between the provided examples of teaching strategies and previously introduced principles and theoretical lenses.

Chapter 4 is particularly devoted to participation in mathematical discussions. The power distribution between teachers and students and Emergent Bilinguals and non-Emergent Bilinguals is discussed with questioning how to encourage all students’ participation. Another significant theory, translanguaging, is explored in Chapter 5, which is closely connected to culturally sustaining pedagogy. We believe translanguaging can shift and challenge the current teaching paradigm, especially with Emergent Bilinguals. Moreover, we discuss a way to help Emergent Bilinguals access word problems using language analysis, representations, and translanguaging approaches.

The last part of the book goes beyond school. Chapter 6 connects mathematical learning to students’ families and communities. We introduce the Community Cultural Wealth Model to explore various capitals that Emergent Bilinguals may have and teachers should be aware of in order to utilize them for teaching. For this structure, we strongly recommend readers follow the order of chapters and try to make connections among the contents of chapters. Each chapter will begin with Thinking Questions Before Reading and end with Thinking Questions After Reading. We made and present these questions in this way on purpose. To maximize your own learning, we hope you pause reading for a while to deeply think about these questions in each chapter.

BUMBLEBEE Post-reading Questions

- How are the facts you read in this chapter different from or similar to what you thought in the beginning?

- Do you have any changed perspectives or expectations related to Emergent Bilinguals through this module reading?

References

Committee on Fostering School Success for English Learners: Toward New Directions in Policy, Practice, and Research, Board on Children, Youth, and Families, Board on Science Education, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education, Health and Medicine Division, & National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2017). Promoting the Educational Success of Children and Youth Learning English: Promising Futures (R. Takanishi & S. L. Menestrel, Eds.). https://doi.org/10.17226/24677

García, O., & Kleifgen, J. A. (2018). Educating emergent bilinguals: Policies, programs, and practices for English learners (Second edition). New York: Teachers College Press.

Jensen, E.B., Knapp, A., Borsella, C., and Nestor, K. (2015). The Place of Birth Composition of Immigrants to the United States: 2000 to 2013. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau.

Pew Research Center. (2012). The Rise of Asian Americans. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center Social & Demographic Trends. Available: https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2012/06/The-Rise-of-Asian-Americans.pdf [June 20, 2016].

- Within the following chapters, you will encounter the acronym BUMBLEBEE and questions associated with it. BUMBLEBEE is an affirmative acronym which stands for “Building Understanding in Mathematics By Leveraging Emergent Bilinguals’ as Equals in Education.” Before reading each chapter, we will ask you some BUMBLEBEE pre-reading questions to help frame the chapter and draw upon your teaching philosophy. After reading the chapter, you will encounter some post-reading BUMBLEBEE questions to reflect on what you have learned and brainstorm how to move forward with this new knowledge. ↵