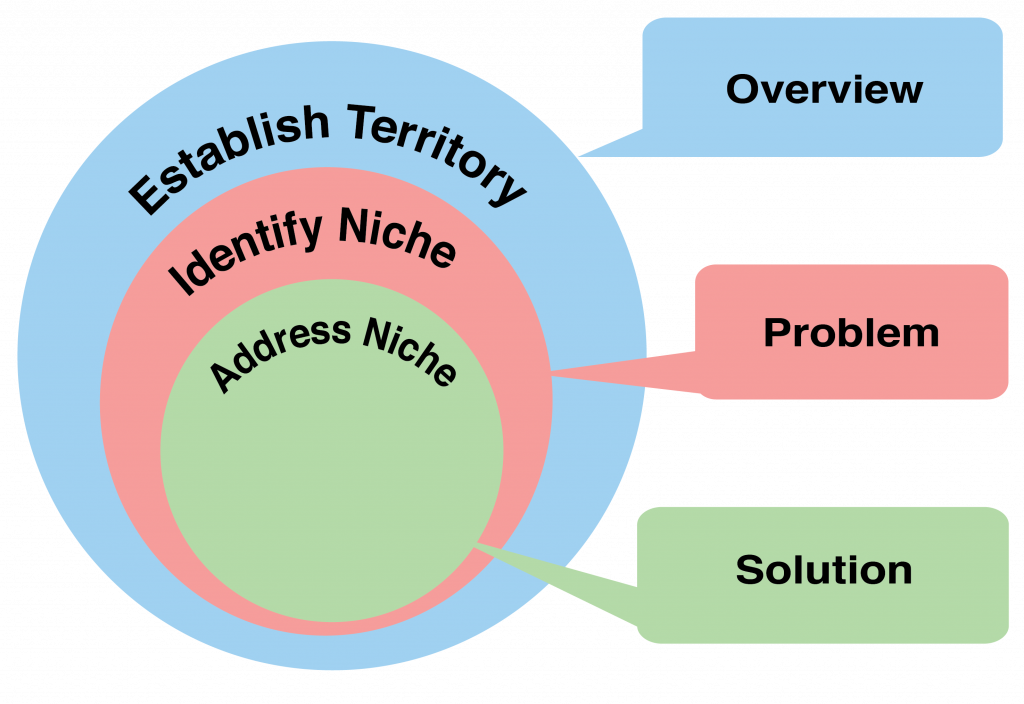

Chapter 3: Writing the Introduction Section

Introduction Goal 3: Addressing the Niche

This goal allows you to indicate how your work/research speaks to the niche that you have carved out for yourself. Usually, this is the last part of the Introduction – the part just before the research questions. However, please don’t forget that these are not “rules.” We are presenting guidelines based on linguistic research investigating published academic journal articles. As a writer, you decide how to organize your writing so that you accomplish these goals. In this last goal, you want to write directly about your purpose and values, and perhaps you’ll want to outline the structure or organization of your article. Basically, you define how your present study addresses the identified niche and how it contributes to the existing research. Also, you can explain – briefly – the outcomes of the project.

Below are some examples of Goal 3 from published research articles. Notice how the bolded parts help the writer to achieve the communicative goal of Addressing the Niche.

Examples

Examples

- This study investigates the construct of writing ability in English and Korean based on elementary school students’ responses to two tasks. Specifically, on the one hand, the study aims to validate the influence of four components of writing ability across both languages: namely, content, grammar, spelling, and text length in writing. On the other, it aims to assess the effect of two tasks on writing performance across both languages.[1]

- In this qualitative study, we interviewed and observed 11 high-reputation plant managers to find out what made them successful. We report their words and actions, and rarely did those managers mention the benefits of technology or the newest analytical tools. Rather, what we saw common among the plant managers in our study – even across several industries – was the effective application of well-honed political skill.[2]

- The coupling of neutrinos to this hydrodynamically unstable matter is central to the supernova problem. In this work, we present new, hitherto unpublished features of the only two-dimensional multi-group, multi-angle neutrino transport calculations of core-collapse supernova evolution ever performed. Results from these simulations were first published by Ott et al. (2008).[3]

In the Academic Phrasebank website, there are numerous examples of phrases and clauses that can be used to accomplish each of the goals we are presenting. Here are a few of them:

|

We’ll discuss more specific language resources (words, phrases, and clauses) that you can use to accomplish this goal at a later point in the chapter. For now, the main point is to understand that Goal 3 carves out a place for your research by pointing out how you are going to solve a problem or fill a gap.

Strategies for Introduction Goal 3

There are multiple ways you can effectively achieve the goal of addressing the niche into which your research fits:

- Introduce your research descriptively

- Announce the purpose of the study

- Present research questions

- Present research hypotheses

- Summarize methods

- Clarify definitions

- Announce principal outcomes

- State value

- Outline the structure

Let’s get a closer look at each strategy to understand how they work.

Introduction Goal 3 Strategy: Introduce Your Research Descriptively

This strategy concerns how writers note the main characteristics of their research. They provide information that highlights their goals and intentions. The strategy also specifically outlines how the objectives of the research address the niche.

Examples

Examples

- It transforms outcomes for each alternative into a common unit with a multi-attribute value (utility) function using weights that reflect the decision makers’ preferences. We report on an MCDA involving the 26 most important stakeholders in two Swiss cases; a general and a psychiatric hospital. Details of the MCDA methodology are given in ref 24 and of the ecotoxicological risk assessment in ref 20.[4]

- Using these data, in this article I examine the validity of the tests by analyzing what the teachers believed the tests measure and what they believed the tests’ impacts are. In essence, this paper investigates the social consequences of a large-scale testing program and scrutinizes not only the intended outcome but also the unintended side effects of the English language tests (Messick, 1989, p. 16). Because the testing in Michigan was required by the federal government?s No Child Left Behind (NCLB) Act, I begin by summarizing that law.[5]

To accomplish this, authors will often use highly contextualized words/phrases, such as this, the present study, we, I, now, and here, which you can see in bold in the examples above. However, you should be aware that this is not the announcement of the goals/aims of the study. This is a more general description of the research. If you would like to be more specific about your objectives, you can implement the strategy presented next.

Introduction Goal 3 Strategy: Announce the Purpose of the Study

This strategy clearly articulates the intentions of the researcher(s) by specifying how the objectives address gaps in the research. It is common for writers to use words, such as aim, purpose, goal, objective, target, etc., to directly state their intentions. The examples below show how this is realized in published articles from high-impact journals:

Examples

Examples

- When this process of mutual adjustment goes well, people may remark that they are ”in synch” or ”on the same wavelength.” One goal of the present article is to show that there is an important literal truth behind these colloquialisms. That is, as people converse and work together, major interpersonal issues–namely, agency and communion–come to have strongly entrained cyclical patterns, making partners’ behaviors as interlocked or interdependent, as if they were dancing together.[6]

- Although Ca2+ signaling in B cells is widely assumed to be essential, the importance of SOC influx for physiological B cell functions was unclear. To directly assess the involvement of SOC influx in B cells , we generated mice with B cell-specific deletions of Stim1 and Stim2. We found that STIM1 and STIM2 critically regulated BCR-induced SOC influx and proliferation in vitro, and yet they were dispensable for B cell development and antibody responses in vivo.[7]

You might also note that it’s common to see phrases with to + a verb (e.g., to show, to compare, to evaluate, etc.). The Academic Phrasebank website also provides some sentence starters:

|

Introduction Goal 3 Strategy: Present Research Questions

Presenting research questions is a strategy for directly stating what queries were made about the data. Authors do this in an effort to specify the focus of the research and to highlight main topics or words that can help the reader navigate the remainder of the manuscript.

Writers who choose to implement this step articulate their questions directly (with a question mark) or indirectly (a question in the form of a statement), both of which are shown below:

Examples

Examples

- From this perspective, strategic planning represents an inertial force that decreases the number of NPD projects. The purpose of our study is to provide empirical evidence on the debated role of strategic planning in generating NPD projects by answering the two questions: (1) does strategic planning increase or decrease the number of NPD projects? and (2) if so, how can a firm manage controllable organizational factors to mitigate the adverse effect of strategic planning on the number of NPD projects for better performance?[8]

- The increase in growth response due to irrigation was relatively small, with no significant increase in basal area (Albaugh et al. 2004). In this study, the questions we attempted to answer were whether the growth gains experienced from fertilization resulted in lower SG and percent latewood, as expected from previous studies; whether SG properties were affected by irrigation, implying the importance of water availability despite limited growth gains; and whether irrigation had an impact on the wood quality of fertilized trees different from that of unfertilized trees.[9]

Direct questions always use question-word order and end with a question mark (?). Some common ways to start a direct question include wh-words such as who, what when, where, how, and why, but research questions can commonly begin with other phrases such as: to what degree, do/did, have/has, etc. Indirect questions sometimes start with words such as whether or if.

Introduction Goal 3 Strategy: Present Research Hypotheses

Presenting research hypotheses is a way for writers to share what they have found or hope to find that is directly relevant to the objectives or questions of the study. Authors utilize this step to introduce the assumptions to be tested, clarify expectations of the findings, and speculate about potential outcomes.

To present their research hypotheses, authors use verbs like hypothesize, suggest, expect, predict, etc., the subjunctive mood (e.g., would expect, could be possible), and modal verbs such as could, might, and may. Consider the following examples:

Examples

Examples

- We focused on school support because of the significant role of environment in influencing human behaviors (Lewin, 1936). We believe that school support, a contextual factor, is intricately related to teacher motivation, a personal factor. [10]

- As previous research has demonstrated that the learners’ view towards a learning environment strongly influences their learning outcomes and learning process, it can be discussed whether program-defined adaptivity is not only effective because of the underlying learner models, but also because the adaptivity is perceived and experienced as such by the learners. In this study, we apply the cognitive mediational paradigm and hypothesize that perceptions of adaptivity mediate the relation between adaptive instruction and learners’ motivations and learning outcomes. [11]

You can use the verb hypothesize or the noun hypothesis, but be careful with replacing that word with synonyms, which could carry different connotations because of their nuanced meanings.

Introduction Goal 3 Strategy: Summarize Methods

The strategy summarizing methods allows writers to present their procedures for the first time. However, you should note that it is a summary of the methods and shouldn’t be too detailed. Here are some examples from published writing:

Examples

Examples

- Recently, Yu et al. (2008a, b) employed a novel EPS fractionation approach to obtain the pellets (cells) by extracting the EPS matrix. In this study, aerobic granules seeded with activated sludge flocs and pellets, respectively, were cultivated in two sequencing batch reactors (SBRs), then these two kinds of granules were both stored at 25 +/- 1 degrees Celsius for 3 weeks. The main purposes of this study were to investigate their responses to storage and explore the mechanism of stability loss.[12]

- We propose that HRO status can be achieved through a systematic process linked to top leadership. We empirically test this proposition by building a model for improving patient safety in hospitals. [13]

Note that this strategy can be implemented by using either passive or active voice. Both are correct, but the decision of whether to use one or the other is usually based on the discipline in which you do research. The Academic Phrasebank website provides other examples, and from the list below, you can see that there are a variety of forms that you can use to effectively realize this strategy:

|

Introduction Goal 3 Strategy: Clarify Definitions

Clarifying definitions is the strategy writers use when they need to inform the reader of terms or concepts as they are used in the research. By implementing this step, authors can explain the meaning of terminology, provide working definitions, and/or clarify concepts. Sometimes scholars use this strategy to demonstrate how the terms or concepts used in the paper are similar to or different from the way the terms are typically used in the field, which helps readers to avoid misinterpreting the wording. The definitions and/or terms used in the study may come from previous research, or they may be new terminology or phrasing that the author has coined. Look at the examples below to take note of how published writers make this happen in their manuscripts:

Examples

Examples

- Some organizations require great attention to preventing mistakes because errors could have serious implications to public safety. High reliability organizations (HROs) refer to organizations or systems that operate in complex and hazardous conditions and yet consistently achieve nearly error-free performance. They are termed HROs because they seem to function in a more reliable fashion than other similar organizations. [14]

- Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is defined as a group of vascular disorders that involve the heart as well as the vasculature. CVD remains the leading cause of death in developed nations and accounts for over one-third of all deaths within the United States each year [1] .[15]

If you’d like to explore more ways to clarify definitions, the Academic Phrasebank website not only provides a list of general ideas, but also includes more specific ways to define words for a variety of different communicative goals (e.g., indicating difficulties to define a term, referring to others’ definitions etc.). Here are a few starter sentences that might help you to envision how writers accomplish the strategy of defining terms, which contributes to addressing the niche:

|

Introduction Goal 3 Strategy: Announce Principal Outcomes

Below are some examples of the announcing principal outcomes strategy:

Examples

Examples

- Instead, the template-bridging effect of the membrane binding to the Gla domains of both fXa and PZ, together with the specific interaction of the two Gla domains shown previously by Rezaie and co-workers (6), were the most important factors in bringing about the PZ-dependent acceleration of fXa inhibition in the presence of phospholipid and Ca2+. Importantly, we found that a ZPI variant with P1 arginine reacted at a diffusion-limited rate with fXa. Reaction was predominantly as a substrate, as a result of rapid acylation and deacylation, and did not depend on PZ or other cofactors.[16]

- The goal of this study was to identify and test the importance of potential drivers of agricultural land abandonment and consequent natural vegetation re-growth, using a spatially explicit statistical model, based on an economic theoretical framework. There are three main findings of this study. Firstly, the research area in the municipality of Ancud, Chiloe Island, in Southern Chile has been proposed by Food and Agriculture Organization of The United Nations (FAO) as a Globally Important Agricultural Heritage System (GIAHS), which sustains itself on the permanence of traditional farming practices that are threatened by land abandonment.[17]

To announce the principal outcomes of their research, authors typically use verbs such as find, show, indicate, reveal, explain, demonstrate, determine, prove, establish, etc. Regardless of the verb you use, however, you want to be sure that you are previewing just the most important findings. You’ll have an entire section of the paper (the Results section) to provide the details.

Introduction Goal 3 Strategy: State Value

Stating the value of present research explains the significance of your research. It functions as a kind of argument that the study provides an important contribution to the field. Here are two examples:

Examples

Examples

- Therefore, this work’s intent was to study the bioaccumulation of the contaminants mentioned previously in the autochthonous black pig feeding substantially on natural pastures and reared under different extensive farming systems within the preserved area of the Regional Nebrodi Park of Sicily (Italy). The acquired information could provide answers to food safety issues for locally processed meat production and, at the same time, endorse the abovementioned sustainable farming practices, i.e., that outdoor and wild pigs be recognized as sensitive sentinels to monitor the overall quality of the environment (36).[18]

- The research we report here offers a possible explanation for why situational cues, such as numerical representation, might contribute to such performance outcomes. We propose that, by triggering objective experiences of identity threat (e.g., cognitive and physiological vigilance) and subjective experiences of identity threat (e.g., a decreased sense of belonging and decreased desire to participate in the setting), subtle situational cues may have powerful and far-reaching effects for potential targets of stereotypes and stigma.[19]

Many writers implement this strategy through the use of verbs such as can, could, might, or may in combination with verbs like offer, provide, generate, or contribute. Other authors use adjectives or adverbs such as possible, potential, likely, or probably. The Academic Phrasebank provides the following sentence starters as suggestions:

|

Introduction Goal 3 Strategy: Outline the Structure

Examples

Examples

- My results can therefore help to explain why models that treat product locations as fixed often do poorly at predicting how prices change after mergers (Peters, 2006; Whinston, 2006; Ashenfelter and Hosken, 2008) and why competitors may choose to lobby an antitrust authority to prohibit a merger even when synergies are unlikely. The article is structured as follows. The rest of the Introduction reviews the related literature. Section 2 describes the data and how I use playlists to measure differentiation. Section 3 presents the main results.[20]

- This article is structured as follows. The second section describes the study sites, the simulated cork oak silviculture models, the data collection, the private amenity valuation, and the afforestation net benefit estimation. The third section presents the main results. The fourth section closes with discussion and conclusions.[21]

Usually, writers who utilize this strategy begin with an overview sentence followed by a list of section-by-section content. The examples above use similar tactics to each other even though they are from very different disciplines. Additionally, the Academic Phrasebank website has a further list of ideas, as noted below:

|

So, there are quite a few strategies for accomplishing the third goal. Now, you will complete an exercise to see how well you can recognize the strategies in published articles.

Key Takeaways

Key Takeaways

The third goal of an Introduction section in a research article is Addressing a Niche. There are nine possible ways to achieve this:

- Introduce research descriptively

- Announce purpose of study

- Present research questions

- Present research hypotheses

- Summarize methods

- Clarify definitions

- Announce principal outcomes

- State value

- Outline the structure

Remember: It’s not necessary to implement all of these strategies. You can choose which ones work best for your own topic, style, and discipline.

- Bae, J., Bachman, L. (2010). “An investigation of four writing traits and two tasks across two languages”, Language Testing 27(2):213-234. ↵

- Smith, A., Plowman, D., Duchon, D., Quinn, A. (2009). “A qualitative study of high-reputation plant managers: political skill and successful outcomes”, Journal of Operations Management 27(6):428-443. ↵

- randt, T., Burrows, A., Ott, C., Livne, E. (2011). “Results from core-collapse simulations with multi-dimensional, multi-angle neutrino transport”, The Astrophysical Journal 728(1):8. ↵

- Lienert, J., Koller, M., Konrad, J., McArdell, C., Schuwirth, N. (2011). “Multiple-criteria decision analysis reveals high stakeholder preference to remove pharmaceuticals from hospital wastewater”, Environmental Science & Technology 45(9):3848-3857. ↵

- Winke, P. (2011). “Evaluating the Validity of a High‐Stakes ESL Test: Why Teachers’ Perceptions Matter”, TESOL Quarterly 45(4):628-660. ↵

- Sadler, P., Ethier, N., Gunn, G., Duong, D., Woody, E. (2009). “Are we on the same wavelength? Interpersonal complementarity as shared cyclical patterns during interactions.”, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 97(6):1005. ↵

- Matsumoto, M., Fujii, Y., Baba, A., Hikida, M., Kurosaki, T., Baba, Y. (2011). “The calcium sensors STIM1 and STIM2 control B cell regulatory function through interleukin-10 production”, Immunity 34(5):703-714. ↵

- Song, M., Im, S., Bij, H., Song, L. (2011). “Does Strategic Planning Enhance or Impede Innovation and Firm Performance?*”, Journal of Product Innovation Management 28(4):503-520. ↵

- Love-Myers, K., Clark, A., Schimleck, L., Dougherty, P., Daniels, R.. (2010). “The effects of irrigation and fertilization on specific gravity of loblolly pine”, Forest Science 56(5):484-493. ↵

- FiLam, S., Cheng, R. W., Choy, H. C. (2010). “School support and teacher motivation to implement project-based learning”, Learning and Instruction, 20, pp. 487-497. ↵

- Vandewaetere, M., Vandercruysse, S., Clarebout, G., “Learners’ perceptions and illusions of adaptivity in computer-based learning environments”, Education Tech Research Dev, pp. NA. ↵

- Xu, H., He, P., Wang, G., Yu, G., Shao, L. (2010). “Enhanced storage stability of aerobic granules seeded with pellets”, Bioresource Technology 101(21):8031-8037. ↵

- McFadden, K., Henagan, S., Gowen III, C. (2009). “The patient safety chain: Transformational leadership’s effect on patient safety culture, initiatives, and outcomes”, Journal of Operations Management 27(5):390-404. ↵

- McFadden, K., Henagan, S., Gowen III, C. (2009). “The patient safety chain: Transformational leadership’s effect on patient safety culture, initiatives, and outcomes”, Journal of Operations Management 27(5):390-404. ↵

- Wood, J., Shah, N., McKee, C., Hughbanks, M., Liliensiek, S., Russell, P., Murphy, C. (2011). “The role of substratum compliance of hydrogels on vascular endothelial cell behavior”, Biomaterials 32(22):5056-5064. ↵

- Huang, X., Dementiev, A., Olson, S., Gettins, P. (2010). “Basis for the specificity and activation of the serpin protein Z-dependent proteinase inhibitor (ZPI) as an inhibitor of membrane-associated factor Xa”, Journal of Biological Chemistry 285(26): 20399-20409. ↵

- Díaza, G. I., Nahuelhuala, L., Echeverríad, C., Maríne, S. (2011). “Drivers of land abandonment in Southern Chile and implications for landscape planning”, Landscape and Urban Planning, 99, pp. 207–217. ↵

- Brambilla, G., De Filippis, S., Iamiceli, A., Iacovella, N., Abate, V., Aronica, V., Di Marco, V., Di Domenico, A. (2010). “Bioaccumulation of dioxin-like substances and selected brominated flame retardant congeners in the fat and livers of black pigs farmed within the Nebrodi Regional Park of Sicily”, Journal of Food Protection® 74(2): 261-269. ↵

- Murphy, M., Steele, C., Gross, J. (2007). “Signaling threat how situational cues affect women in math, science, and engineering settings”, Psychological Science 18(10):879-885. ↵

- Sweeting, A. (2010). “The effects of mergers on product positioning: evidence from the music radio industry”, The RAND Journal of Economics 41(2): 372-397. ↵

- Ovando, P., Campos, P., Oviedo, J., Montero, G. (2010). “Private Net Benefits from Afforesting Marginal Cropland and Shrubland with Cork Oaks in Spain”, Forest Science 56(6): 567-577. ↵