Emerging and Early Adulthood

Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French

Historically, early adulthood spanned from approximately 18 years (the end of adolescence) until 40 to 45 years (beginning of middle adulthood). More recently, developmentalists have divided this age period into two separate stages: Emerging adulthood followed by early adulthood. Although these age periods differ in their physical, cognitive, and social development, overall the age period from 18 years to 45 years is a time of peak physical capabilities and the emergence of more mature cognitive development, financial independence, and intimate relationships.[1]

Emerging Adulthood

Emerging adulthood is the period between the late teens and early twenties; ages 18-25 years, although some researchers have included up to age 29 years in the definition.[2] Jeffrey Arnett (2000) argues that emerging adulthood is neither adolescence nor is it young adulthood.[3] Individuals in this age period have left behind the relative dependency of childhood and adolescence, but have not yet taken on the responsibilities of adulthood. “Emerging adulthood is a time of life when many different directions remain possible, when little about the future is decided for certain, when the scope of independent exploration of life’s possibilities is greater for most people than it will be at any other period of the life course” (p. 469).[4]

Arnett has identified five characteristics of emerging adulthood that distinguishes it from adolescence and young adulthood.[5]

- It is the age of identity exploration. In 1950, Erik Erikson proposed that it was during adolescence that humans wrestled with the question of identity. Yet, even Erikson (1968) commented on a trend during the 20th century of a “prolonged adolescence” in industrialized societies. Today, most identity development occurs during the late teens and early twenties rather than adolescence. It is during emerging adulthood that people are exploring their career choices and ideas about intimate relationships, setting the foundation for adulthood.

- Arnett also described this time period as the age of instability.[6] Exploration generates uncertainty and instability. Emerging adults change jobs, relationships, and residences more frequently than other age groups.

- This is also the age of self-focus. Being self-focused is not the same as being “self- centered.” Adolescents are more self-centered than emerging adults. Arnett reports that in his research, he found emerging adults to be very considerate of the feelings of others, especially their parents. They now begin to see their parents as people not just parents, something most adolescents fail to do.[7] Nonetheless, emerging adults focus more on themselves, as they realize that they have few obligations to others and that this is the time where they can do what they want with their life.

- This is also the age of feeling in-between. When asked if they feel like adults, more 18 to 25 year-olds answer “yes and no” than do teens or adults over the age of 25.[8] Most emerging adults have gone through the changes of puberty, are typically no longer in high school, and many have also moved out of their parents’ home. Thus, they no longer feel as dependent as they did as teenagers. Yet, they may still be financially dependent on their parents to some degree, and they have not completely attained some of the indicators of adulthood, such as finishing their education, obtaining a good full-time job, being in a committed relationship, or being responsible for others. It is not surprising that Arnett found that 60% of 18 to 25 year-olds felt that in some ways they were adults, but in some ways they were not.[9]

- Finally, emerging adulthood is the age of possibilities. It is a time period of optimism as more 18 to 25 year-olds feel that they will someday get to where they want to be in life. Arnett suggests that this optimism is because these dreams have yet to be tested.[10],

For example, it is easier to believe that you will eventually find your soul mate when you have yet to have had a serious relationship. It may also be a chance to change directions, for those whose lives up to this point have been difficult. The experiences of children and teens are influenced by the choices and decisions of their parents. If the parents are dysfunctional, there is little a child can do about it. In emerging adulthood, people can move out and move on. They have the chance to transform their lives and move away from unhealthy environments. Even those whose lives were happier and more fulfilling as children, now have the opportunity in emerging adulthood to become independent and make decisions about the direction they would like their life to take.

Cultural Variations

The five features proposed in the theory of emerging adulthood originally were based on research involving about 300 Americans between ages 18 and 29 from various ethnic groups, social classes, and geographical regions.[11] To what extent does the theory of emerging adulthood apply internationally?

The answer to this question depends greatly on what part of the world is considered. Demographers make a useful distinction between the developing countries that comprise the majority of the world’s population and the economically developed countries that are part of the Organization for Economic Co- operation and Development (OECD), including the United States, Canada, Western Europe, Japan, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand. The current population of OECD countries (also called developed countries) is 1.2 billion, about 18% of the total world population.[12] The rest of the human population resides in developing countries, which have much lower median incomes, much lower median educational attainment, and much higher incidence of illness, disease, and early death. Let us consider emerging adulthood in other OECD countries as little is known about the experiences of 18- 25 year-olds in developing countries.

The same demographic changes as described above for the United States have taken place in other OECD countries as well. This is true of participation in postsecondary education, as well as median ages for entering marriage and parenthood.[13] However, there is also substantial variability in how emerging adulthood is experienced across OECD countries. Europe is the region where emerging adulthood is longest and most leisurely. The median ages for entering marriage and parenthood are near 30 in most European countries.[14]

Europe today is the location of the most affluent, generous, and egalitarian societies in the world, in fact, in human history.[15] Governments pay for tertiary education, assist young people in finding jobs, and provide generous unemployment benefits for those who cannot find work. In northern Europe, many governments also provide housing support. Emerging adults in European societies make the most of these advantages, gradually making their way to adulthood during their twenties while enjoying travel and leisure with friends.

The lives of emerging adults in developed Asian countries, such as Japan and South Korea, are in some ways similar to the lives of emerging adults in Europe and in some ways strikingly different. Like emerging European adults, emerging adults in Asian tend to enter marriage and parenthood around age 30 years.[16] Like emerging adults in Europe, emerging adults in Japan and South Korea enjoy the benefits of living in affluent societies with generous social welfare systems that provide support for them in making the transition to adulthood, including free university education and substantial unemployment benefits.

However, in other ways, the experience of emerging adulthood in Asian OECD countries is markedly different than in Europe. Europe has a long history of individualism, and today’s emerging adults carry that legacy with them in their focus on self-development and leisure during emerging adulthood. In contrast, most Asian cultures have a shared cultural history emphasizing collectivism and family obligations.

Although Asian cultures have become more individualistic in recent decades, as a consequence of globalization, the legacy of collectivism persists in the lives of emerging adults. They pursue identity explorations and self-development during emerging adulthood, like their American and European counterparts, but within narrower boundaries set by their sense of obligations to others, especially their parents.[17] For example, in their views of the most important criteria for becoming an adult, emerging adults in the United States and Europe consistently rank financial independence among the most important markers of adulthood. In contrast, emerging adults with an Asian cultural background especially emphasize becoming capable of supporting parents financially as among the most important criteria.[18] [19] This sense of family obligation may curtail their identity explorations in emerging adulthood to some extent, as they pay more heed to their parents’ wishes about what they should study, what job they should take, and where they should live than emerging adults do in the West.[20]

When Does Adulthood Begin?

According to Rankin and Kenyon (2008), historically the process of becoming an adult was more clearly marked by rites of passage.[21] For many individuals, marriage and becoming a parent were considered entry into adulthood. However, these role transitions are no longer considered as the important markers of adulthood.[22] Economic and social changes have resulted in increase in young adults attending college and a delay in marriage and having children.[23] [24] Consequently, current research has found financial independence and accepting responsibility for oneself to be the most important markers of adulthood in Western culture across age and ethnic groups.[25]

In looking at college students’ perceptions of adulthood, Rankin and Kenyon (2008) found that some students still view rites of passage as important markers.[26] College students who had placed more importance on role transition markers, such as parenthood and marriage, belonged to a fraternity/sorority, were traditionally aged (18–25), belonged to an ethnic minority, were of a traditional marital status; i.e., not cohabitating, or belonged to a religious organization, particularly for men. These findings supported the view that people holding collectivist or more traditional values place more importance on role transitions as markers of adulthood. In contrast, older college students and those cohabitating did not value role transitions as markers of adulthood as strongly.

Obesity

Although at the peak of physical health, a concern for early adults is the current rate of obesity. Results from the 2015 National Center for Health Statistics indicate that an estimated 70.7% of U.S. adults aged 20 and over are overweight and 37.9% are obese.[27] Body mass index (BMI), expressed as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared (kg/m2), is commonly used to classify overweight (BMI 25.0–29.9), obesity (BMI greater than or equal to 30.0), and extreme obesity (BMI greater than or equal to 40.0). The 2015 statistics are an increase from the 2013-2014 statistics that indicated that an estimated 35.1% were obese, and 6.4% extremely obese.[28] In 2003-2004, 32% of American adults were identified as obese. The CDC also indicated that one’s 20s are the prime time to gain weight as the average person gains one to two pounds per year from early adulthood into middle adulthood. The average man in his 20s weighs around 185 pounds and by his 30s weighs approximately 200 pounds. The average American woman weighs 162 pounds in her 20s and 170 pounds in her 30s.

The American obesity crisis is also reflected worldwide.[29] Although obesity is seen throughout the world, more obese men and women live in China and the USA than in any other country. Figure 2 illustrates how waist circumference is also used as a measure of obesity. Figure 3 demonstrates the percentage of growth for males and females identified as obese between 1960 and 2012.

Causes of Obesity

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2016), obesity originates from a complex set of contributing factors, including one’s environment, behavior, and genetics. Societal factors include culture, education, food marketing and promotion, the quality of food, and the physical activity environment available. Behaviors leading to obesity include diet, the amount of physical activity, and medication use. Lastly, there does not appear to be a single gene responsible for obesity. Rather, research has identified variants in several genes that may contribute to obesity by increasing hunger and food intake. Another genetic explanation is the mismatch between today’s environment and “energy-thrifty genes” that multiplied in the distant past, when food sources were unpredictable. The genes that helped our ancestors survive occasional famines are now being challenged by environments in which food is plentiful all the time. Overall, obesity most likely results from complex interactions among the environment and multiple genes.

Obesity Health Consequences

Obesity is considered to be one of the leading causes of death in the United States and worldwide. According to the CDC (2016) compared to those with a normal or healthy weight, people who are obese are at increased risk for many serious diseases and health conditions including:[30]

- All-causes of death (mortality)

- High blood pressure (Hypertension)

- High LDL cholesterol, low HDL cholesterol, or high levels of triglycerides (Dyslipidemia)

- Type 2 diabetes

- Coronary heart disease

- Stroke

- Gallbladder disease

- Osteoarthritis (a breakdown of cartilage and bone within a joint)

- Sleep apnea and breathing problems

- Some cancers (endometrial, breast, colon, kidney, gallbladder, and liver)

- Low quality of life

- Mental illness such as clinical depression, anxiety, and other mental disorders

- Body pain and difficulty with physical functioning

A Healthy, but Risky Time

Doctor’s visits are less frequent in early adulthood than for those in midlife and late adulthood and are necessitated primarily by injury and pregnancy.[31] However, the top five causes of death in emerging and early adulthood are non-intentional injury (including motor vehicle accidents), homicide, and suicide with cancer and heart disease completing the list.[32] Rates of violent death (homicide, suicide, and accidents) are highest among young adult males, and vary by race and ethnicity. Rates of violent death are higher in the United States than in Canada, Mexico, Japan, and other selected countries. Males are more likely to die in auto accidents than are females.[33]

Alcohol Abuse

A significant contributing factor to risky behavior is alcohol. According to the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), 88% of people ages 18 or older reported that they drank alcohol at some point in their lifetime; 71% reported that they drank in the past year; and 57% reported drinking in the past month.[34] Additionally, 6.7% reported that they engaged in heavy drinking in the past month. Heavy drinking is defined as drinking five or more drinks on the same occasion on each of five or more days in the past 30 days. Nearly 88,000 people (approximately 62,000 men and 26,000 women) die from alcohol-related causes annually, making it the fourth leading preventable cause of death in the United States. In 2014, alcohol-impaired driving fatalities accounted for 9,967 deaths (31% of overall driving fatalities).

The NIAAA defines binge drinking when blood alcohol concentration levels reach 0.08 g/dL. This typically occurs after four drinks for women and five drinks for men in approximately two hours. In 2014, 25% of people ages 18 or older reported that they engaged in binge drinking in the past month. According to the NIAAA (2015) “Binge drinking poses serious health and safety risks, including car crashes, drunk-driving arrests, sexual assaults, and injuries. Over the long term, frequent binge drinking can damage the liver and other organs,” (p. 1).[35]

Alcohol and College Students

Results from the 2014 survey demonstrated a difference between the amount of alcohol consumed by college students and those of the same age who are not in college.[36] Specifically, 60% of full-time college students’ ages 18–22 drank alcohol in the past month compared with 51.5% of other persons of the same age not in college. In addition, 38% of college students’ ages 18–22 engaged in binge drinking; that is, five or more drinks on one occasion in the past month, compared with 33.5% of other persons of the same age. Lastly, 12% of college students’ (ages 18–22) engaged in heavy drinking; that is, binge drinking on five or more occasions per month, in the past month. This compares with 9.5% of other emerging adults not in college.

The consequences for college drinking are staggering, and the NIAAA (2016) estimates that each year the following occur:

- 1,825 college students between the ages of 18 and 24 die from alcohol-related unintentional injuries, including motor-vehicle crashes.

- 696,000 students between the ages of 18 and 24 are assaulted by another student who has been drinking.

- Roughly 1 in 5 college students meet the criteria for an Alcohol Use Disorder.

- About 1 in 4 college students report academic consequences from drinking, including missing class, falling behind in class, doing poorly on exams or papers, and receiving lower grades overall. (p. 1)

- 97,000 students between the ages of 18 and 24 report experiencing alcohol-related sexual assault or date rape.

The role alcohol plays in predicting acquaintance rape on college campuses is of particular concern. “Alcohol use in one the strongest predictors of rape and sexual assault on college campuses,” (p. 454).[37] Krebs, Lindquist, Warner, Fisher and Martin (2009) found that over 80% of sexual assaults on college campuses involved alcohol.[38] Being intoxicated increases a female’s risk of being the victim of date or acquaintance rape.[39] Females are more likely to blame themselves and to be blamed by others if they were intoxicated when raped. College students view perpetrators who were drinking as less responsible, and victims who were drinking as more responsible for the assaults.[40]

Factors Affecting College Students’ Drinking

Several factors associated with college life affect a student’s involvement with alcohol.[41] These include the pervasive availability of alcohol, inconsistent enforcement of underage drinking laws, unstructured time, coping with stressors, and limited interactions with parents and other adults. Due to social pressures to conform and expectations when entering college, the first six weeks of freshman year are an especially susceptible time for students. Additionally, more drinking occurs in colleges with active Greek systems and athletic programs. Alcohol consumption is lowest among students living with their families and commuting, while it is highest among those living in fraternities and sororities.

College Strategies to Curb Drinking

Strategies to address college drinking involve the individual-level and campus community as a whole. Identifying at-risk groups, such as first year students, members of fraternities and sororities, and athletes has proven helpful in changing students’ knowledge, attitudes, and behavior regarding alcohol.[42] Interventions include education and awareness programs, as well as intervention by health professionals. At the college-level, reducing the availability of alcohol has proven effective by decreasing both consumption and negative consequences.

Non-Alcohol Substance Use

Illicit drug use peaks between the ages of 19 and 22 and then begins to decline. Additionally, 25% of those who smoke cigarettes, 33% of those who smoke marijuana, and 70% of those who abuse cocaine began using after age 17.[43] Emerging adults (18 to 25) are the largest abusers of prescription opioid pain relievers, anti-anxiety medications, and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder medication.[44] In 2014 more than 1700 emerging adults died from a prescription drug overdose. This is an increase of four times since 1999. Additionally, for every death there were 119 emergency room visits.

Daily marijuana use is at the highest level in three decades.[45] For those in college, 2019 data indicate that 5.9% of college students smoke marijuana daily, while only 2% smoked daily in 1994. For non-college students of the same age, the daily percentage is over twice as high (approximately 15%). Additionally, daily cigarette smoking is lower for those in college as only 7.9% smoked in the past month, while for those not in college was 16%.[46]

Rates of violent death are influenced by substance use which peaks during emerging and early adulthood. Drugs impair judgment, reduce inhibitions, and alter mood, all of which can lead to dangerous behavior. Reckless driving, violent altercations, and forced sexual encounters are some examples. Drug and alcohol use increase the risk of sexually transmitted infections because people are more likely to engage in risky sexual behavior when under the influence. This includes having sex with someone who has had multiple partners, having anal sex without the use of a condom, having multiple partners, or having sex with someone whose history is unknown. Lastly, as previously discussed, drugs and alcohol ingested during pregnancy have a teratogenic effect on the developing embryo and fetus.

Beyond Formal Operational Thought

According to Piaget’s theory, adolescents acquire formal operational thought as they. The hallmark of this type of thinking is the ability to think abstractly or to consider possibilities and ideas about circumstances never directly experienced. Thinking abstractly is only one characteristic of adult thought, however. If you compare a 15 year-old with someone in their late 30s, you would probably find that the latter considers not only what is possible, but also what is likely. Why the change? The adult has gained experience and understands why possibilities do not always become realities. They learn to base decisions on what is realistic and practical, not idealistic, and can make adaptive choices. Adults are also not as influenced by what others think. This advanced type of thinking is referred to as postformal Thought.[47]

In addition to moving toward more practical considerations, thinking in early adulthood may also become more flexible and balanced. Abstract ideas that the adolescent believes in firmly may become standards by which the adult evaluates reality. Adolescents tend to think in dichotomies; ideas are true or false; good or bad; and there is no middle ground. However, with experience, the adult comes to recognize that there is some right and some wrong in each position, some good or some bad in a policy or approach, some truth and some falsity in a particular idea. This ability to bring together salient aspects of two opposing viewpoints or positions is referred to as dialectical thought and is considered one of the most advanced aspects of postformal thinking.[48] Such thinking is more realistic because very few positions, ideas, situations, or people are completely right or wrong. So, for example, parents who were considered angels or devils by the adolescent eventually become just people with strengths and weaknesses, endearing qualities, and faults to the adult.

Does everyone reach post-formal or even formal operational thought?

Formal operational thought involves being able to think abstractly; however, this ability does not apply to all situations or all adults. Formal operational thought is influenced by experience and education. Some adults lead lives in which they are not challenged to think abstractly about their world. Many adults do not receive any formal education and are not taught to think abstractly about situations they have never experienced. Further, they are also not exposed to conceptual tools used to formally analyze hypothetical situations. Those who do think abstractly, in fact, may be able to do so more easily in some subjects than others. For example, psychology majors may be able to think abstractly about psychology, but be unable to use abstract reasoning in physics or chemistry. Abstract reasoning in a particular field requires a knowledge base that we might not have in all areas. Consequently, our ability to think abstractly depends to a large extent on our experiences.

Attachment in Young Adulthood

Hazan and Shaver (1987) described the attachment styles of adults, using the same three general categories proposed by Ainsworth’s research on young children; secure, avoidant, and anxious/ambivalent.[49] Hazan and Shaver developed three brief paragraphs describing the three adult attachment styles. Adults were then asked to think about romantic relationships they were in and select the paragraph that best described the way they felt, thought, and behaved in these relationships (See Table 1).

|

Secure |

I find it relatively easy to get close to others and am comfortable depending on them and having them depend on me. I don’t often worry about being abandoned or about someone getting too close to me. |

|---|---|

|

Avoidant |

I am somewhat uncomfortable being close to others; I find it difficult to trust them completely, difficult to allow myself to depend on them. I am nervous when anyone gets too close, and often, love partners want me to be more intimate than I feel comfortable being. |

|

Anxious/Ambivalent |

I find that others are reluctant to get as close as I would like. I often worry that my partner doesn’t really love me or won’t stay with me. I want to merge completely with another person, and this sometimes scares people away. |

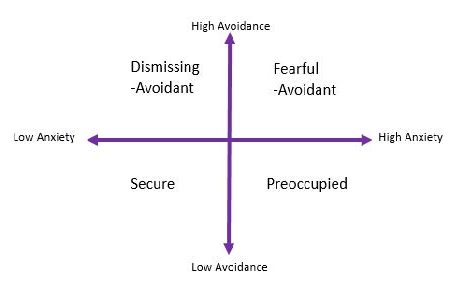

Bartholomew (1990) challenged the categorical view of attachment in adults and suggested that adult attachment was best described as varying along two dimensions; attachment related-anxiety and attachment-related avoidance.[51] Attachment-related anxiety refers to the extent to which an adult worries about whether their partner really loves them. Those who score high on this dimension fear that their partner will reject or abandon them.[52] Attachment-related avoidance refers to whether an adult can open up to others, and whether they trust and feel they can depend on others. Those who score high on attachment-related avoidance are uncomfortable with opening up and may fear that such dependency may limit their sense of autonomy. According to Bartholomew (1990) this would yield four possible attachment styles in adults; secure, dismissing, preoccupied, and fearful-avoidant (see Figure 5).[53]

Securely attached adults score lower on both dimensions. They are comfortable trusting their partners and do not worry excessively about their partner’s love for them. Adults with a dismissing style score low on attachment-related anxiety, but higher on attachment-related avoidance. Such adults dismiss the importance of relationships. They trust themselves but do not trust others, thus do not share their dreams, goals, and fears with others. They do not depend on other people and feel uncomfortable when they have to do so.

Those with a preoccupied attachment are low in attachment-related avoidance, but high in attachment-related anxiety. Such adults are often prone to jealousy and worry that their partner does not love them as much as they need to be loved. Adults whose attachment style is fearful-avoidant score high on both attachment-related avoidance and attachment-related anxiety. These adults want close relationships, but do not feel comfortable getting emotionally close to others. They have trust issues with others and often do not trust their own social skills in maintaining relationships.

Research on attachment in adulthood has found that:

- Adults with insecure attachments report lower satisfaction in their relationships.[54]

- Those high in attachment-related anxiety report more daily conflict in their relationships.[55]

- Those with avoidant attachment exhibit less support to their partners.[56]

- Young adults show greater attachment-related anxiety than do middle-aged or older adults.[57]

- Some studies report that young adults show more attachment-related avoidance,[58] while other studies find that middle-aged adults show higher avoidance than younger or older adults.[59]

- Young adults with more secure and positive relationships with their parents make the transition to adulthood more easily than do those with more insecure attachments.[60]

Do people with certain attachment styles attract those with similar styles?

When people are asked what kinds of psychological or behavioral qualities they are seeking in a romantic partner, a large majority of people indicate that they are seeking someone who is kind, caring, trustworthy, and understanding, that is the kinds of attributes that characterize a “secure” caregiver.[61] However, we know that people do not always end up with others who meet their ideals. Are secure people more likely to end up with secure partners, and, vice versa, are insecure people more likely to end up with insecure partners? The majority of the research that has been conducted to date suggests that the answer is “yes.” Frazier, Byer, Fischer, Wright, and DeBord (1996) studied the attachment patterns of more than 83 heterosexual couples and found that, if the man was relatively secure, the woman was also likely to be secure.[62]

One important question is whether these findings exist because (a) secure people are more likely to be attracted to other secure people, (b) secure people are likely to create security in their partners over time, or (c) some combination of these possibilities. Existing empirical research strongly supports the first alternative. For example, when people have the opportunity to interact with individuals who vary in security in a speed-dating context, they express a greater interest in those who are more secure rather than those who are more insecure.[63] However, there is also some evidence that people’s attachment styles mutually shape one another in close relationships. For example, in a longitudinal study, Hudson, Fraley, Vicary, and Brumbaugh (2012) found that, if one person in a relationship experienced a change in security, the person’s partner was likely to experience a change in the same direction.[64]

Do early experiences as children shape adult attachment?

The majority of research on this issue is retrospective; that is, it relies on adults’ reports of what they recall about their childhood experiences. This kind of work suggests that secure adults are more likely to describe their early childhood experiences with their parents as being supportive, loving, and kind.[65] A number of longitudinal studies are emerging that demonstrate prospective associations between early attachment experiences and adult attachment styles and/or interpersonal functioning in adulthood. For example, Fraley, Roisman, Booth-LaForce, Owen, and Holland (2013) found in a sample of more than 700 individuals studied from infancy to adulthood that maternal sensitivity across development prospectively predicted security at age 18.[66] Simpson, Collins, Tran, and Haydon (2007) found that attachment security, assessed in infancy in the strange situation, predicted peer competence in grades one to three, which, in turn, predicted the quality of friendship relationships at age 16, which, in turn, predicted the expression of positive and negative emotions in their adult romantic relationships at ages 20 to 23.[67]

It is easy to come away from such findings with the mistaken assumption that early experiences “determine” later outcomes. To be clear: Attachment theorists assume that the relationship between early experiences and subsequent outcomes is probabilistic, not deterministic. Having supportive and responsive experiences with caregivers early in life is assumed to set the stage for positive social development. But that does not mean that attachment patterns are set in stone. In short, even if an individual has far from optimal experiences in early life, attachment theory suggests that it is possible for that individual to develop well-functioning adult relationships through a number of corrective experiences, including relationships with siblings, other family members, teachers, and close friends. Security is best viewed as a culmination of a person’s attachment history rather than a reflection of his or her early experiences alone. Those early experiences are considered important, not because they determine a person’s fate, but because they provide the foundation for subsequent experiences.

Relationships with Parents/Caregivers and Siblings

In early adulthood the parent-child relationship has to transition toward a relationship between two adults. This involves a reappraisal of the relationship by both parents and young adults. One of the biggest challenges for parents/caregivers, especially during emerging adulthood, is coming to terms with the adult status of their children. Aquilino (2006) suggests that parents who are reluctant or unable to do so may hinder young adults’ identity development.[68] This problem becomes more pronounced when young adults still reside with their parents. Arnett (2004) reported that leaving home often helped promote psychological growth and independence in early adulthood.[69]

Sibling relationships are one of the longest-lasting bonds in people’s lives. Yet, there is little research on the nature of sibling relationships in adulthood.[70] What is known is that the nature of these relationships change, as adults have a choice as to whether they will maintain a close bond and continue to be a part of the life of a sibling. Siblings must make the same reappraisal of each other as adults, as parents have to with their adult children. Research has shown a decline in the frequency of interactions between siblings during early adulthood, as presumably peers, romantic relationships, and children become more central to the lives of young adults. Aquilino (2006) suggests that the task in early adulthood may be to maintain enough of a bond so that there will be a foundation for this relationship in later life.[71] Those who are successful can often move away from the “older-younger” sibling conflicts of childhood, toward a more equal relationship between two adults. Siblings that were close to each other in childhood are typically close in adulthood,[72] and in fact, it is unusual for siblings to develop closeness for the first time in adulthood. Overall, the majority of adult sibling relationships are close.[73]

Erikson: Intimacy versus Isolation

Erikson’s sixth stage focuses on establishing intimate relationships or risking social isolation.[74] Intimate relationships are more difficult if one is still struggling with identity. Achieving a sense of identity is a life-long process, as there are periods of identity crisis and stability. However, once identity is established intimate relationships can be pursued.[75]

These intimate relationships include acquaintanceships and friendships, but also the more important close relationships, which are the long-term romantic relationships that we develop with another person, for instance, in a marriage.[76]

- This chapter is adapted from Lifespan Development by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French, licensed CC BY NC SA. https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-lifespandevelopment/ ↵

- Society for the Study of Emerging Adulthood (SSEA). (2016). Overview. Retrieved from http://ssea.org/about/index.htm ↵

- Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55, 469-480. ↵

- Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55, 469-480. ↵

- Arnett, J. J. (2006). G. Stanley Hall’s adolescence: Brilliance and non-sense. History of Psychology, 9, 186-197. ↵

- Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55, 469-480. ↵

- Arnett, J. J. (2006). G. Stanley Hall’s adolescence: Brilliance and non-sense. History of Psychology, 9, 186-197. ↵

- Arnett, J. J. (2001). Conceptions of the transitions to adulthood: Perspectives from adolescence to midlife. Journal of Adult Development, 8, 133-143. ↵

- Arnett, J. J. (2001). Conceptions of the transitions to adulthood: Perspectives from adolescence to midlife. Journal of Adult Development, 8, 133-143. ↵

- Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55, 469-480. ↵

- Arnett, J. J. (2004). Conceptions of the transition to adulthood among emerging adults in American ethnic groups. In J. J. Arnett & N. Galambos (Eds.), Cultural conceptions of the transition to adulthood: New directions in child and adolescent development. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. ↵

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). (2011). Human development report. NY: Oxford University Press. ↵

- UNdata (2010). Gross enrollment ratio in tertiary education. United Nations Statistics Division. Retrieved November 5, 2010, from http://data.un.org/Data.aspx?d=GenderStat&f=inID:68 ↵

- Douglass, C. B. (2007). From duty to desire: Emerging adulthood in Europe and its consequences. Child Development Perspectives, 1, 101–108. ↵

- Arnett, J.J. (2007). The long and leisurely route: Coming of age in Europe today. Current History, 106, 130-136. ↵

- Arnett, J. J. (2011). Emerging adulthood(s): The cultural psychology of a new life stage. In L.A. Jensen (Ed.), Bridging cultural and developmental psychology: New syntheses in theory, research, and policy (pp. 255–275). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ↵

- Phinney, J. S. & Baldelomar, O. A. (2011). Identity development in multiple cultural contexts. In L. A. Jensen (Ed.), Bridging cultural and developmental psychology: New syntheses in theory, research and policy (pp. 161-186). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ↵

- Arnett, J. J. (2003). Conceptions of the transition to adulthood among emerging adults in American ethnic groups. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 100, 63–75. ↵

- Nelson, L. J., Badger, S., & Wu, B. (2004). The influence of culture in emerging adulthood: Perspectives of Chinese college students. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 28, 26–36. ↵

- Rosenberger, N. (2007). Rethinking emerging adulthood in Japan: Perspectives from long-term single women. Child Development Perspectives, 1, 92–95. ↵

- Rankin, L. A. & Kenyon, D. B. (2008). Demarcating role transitions as indicators of adulthood in the 21st century. Who are they? Journal of Adult Development, 15(2), 87-92. doi: 10.1007/s10804-007-9035-2 ↵

- Arnett, J. J. (2001). Conceptions of the transitions to adulthood: Perspectives from adolescence to midlife. Journal of Adult Development, 8, 133-143. ↵

- Rankin, L. A. & Kenyon, D. B. (2008). Demarcating role transitions as indicators of adulthood in the 21st century. Who are they? Journal of Adult Development, 15(2), 87-92. doi: 10.1007/s10804-007-9035-2 ↵

- Arnett, J. J., & Taber, S. (1994). Adolescence terminable and interminable: When does adolescence end? Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 23, 517–537. ↵

- Arnett, J. J. (2004). Conceptions of the transition to adulthood among emerging adults in American ethnic groups. In J. J. Arnett & N. Galambos (Eds.), Cultural conceptions of the transition to adulthood: New directions in child and adolescent development. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. ↵

- Rankin, L. A. & Kenyon, D. B. (2008). Demarcating role transitions as indicators of adulthood in the 21st century. Who are they? Journal of Adult Development, 15(2), 87-92. doi: 10.1007/s10804-007-9035-2 ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015). Obesity and overweight. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/obesity-overweight.htm ↵

- Fryar, C. D., Carroll, M. D., & Ogden, C. L. (2014). Prevalence of overweight, obesity, and extreme obesity among adults: United States, 1960-1962 through 2011-2012. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/obesity_adult_11_12/obesity_adult_11_12.htm ↵

- Wighton, K. (2016). World’s obese population hits 640 million, according to largest ever study. Imperial College. Retrieved from http://www3.imperial.ac.uh/newsandeventspggrp/imperialcollege/newssummary/news_311-3-2016-22-34-39 ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016). Adult obesity causes and consequences. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/obesity/adult/causes.html ↵

- Berger, K. S. (2005). The developing person through the life span (6th ed.). New York: Worth. ↵

- Heron, M. P., & Smith, B. L. (2007). Products - Health E Stats - Homepage. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved from ↵

- Frieden, T. (2011, January 14). Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report for the Centers for Disease Control. Center for Disease Control. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/su6001al.htm?s_su6001al_w ↵

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. (2016). Alcohol facts and statistics. Retrieved from http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/AlcoholFacts&Stats/AlcoholFacts&Stats.htm ↵

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. (2015). College Drinking. Retrieved from http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/CollegeFactSheet/CollegeFact.htm ↵

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. (2016). Alcohol facts and statistics. Retrieved from http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/AlcoholFacts&Stats/AlcoholFacts&Stats.htm ↵

- Carroll, J. L. (2016). Sexuality now: Embracing diversity (5th ed.). Boston, MA: Cengage Learning. ↵

- Krebs, C., Lindquist, C., Warner, T., Fisher, B., & Martin, S. (2009). College women’s experiences with physically forced, alcohol or other drug-enabled, and drug-facilitated sexual assault before and since entering college. Journal of American College Health, 57(6), 639-649. ↵

- Carroll, J. L. (2007). Sexuality now: Embracing diversity (2nd ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson Learning. ↵

- Untied, A., Orchowski, L., Mastroleo, N., & Gidycz, C. (2012). College students’ social reactions to the victim in a hypothetical sexual assault scenario: The role of victim and perpetrator alcohol use. Violence and Victims, 27(6), 957-972. ↵

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. (2015). College Drinking. Retrieved from http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/CollegeFactSheet/CollegeFact.htm ↵

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. (2015). College Drinking. Retrieved from http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/CollegeFactSheet/CollegeFact.htm ↵

- Volkow, N. D. (2004). Exploring the Whys of Adolescent Drug Use. United States, National Institute on Drug Abuse. Retrieved from http://www.drugabuse.gov/NIDA_notes/NNvol19N3/DirRepVol19N3.html ↵

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2015). College-age and young adults. Retrieved from https://www.drugabuse.gov/related- topics/college-age-young-adults/college-addiction-studies-programs ↵

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2015). College-age and young adults. Retrieved from https://www.drugabuse.gov/related- topics/college-age-young-adults/college-addiction-studies-programs ↵

- National Institutes of Health. (2020). Vaping, marijuana use in 2019 rose in college age adults. Retrieved from https://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/vaping-marijuana-use-2019-rose-college-age-adults ↵

- Sinnott, J. D. (1998). The development of logic in adulthood. NY: Plenum Press. ↵

- Basseches, M. (1984). Dialectical thinking and adult development. Norwood, NJ: Ablex Pub. ↵

- Hazan, C., & Shaver, P. (1987). Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52 (3), 511-524. ↵

- Adapted from Hazan, C., & Shaver, P. (1987) Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 511-524. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.52.3.511 ↵

- Bartholomew, K. (1990). Avoidance of intimacy: An attachment perspective. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 7, 147-178. DOI: 10.1037/0022-3524.61.2.226. ↵

- Fraley, R. C., Hudson, N. W., Heffernan, M. E., & Segal, N. (2015). Are adult attachment styles categorical or dimensional? A taxometric analysis of general and relationship-specific attachment orientations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109 (2), 354-368. ↵

- Bartholomew, K. (1990). Avoidance of intimacy: An attachment perspective. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 7, 147-178. DOI: 10.1037/0022-3524.61.2.226. ↵

- Butzer, B., & Campbell, L. (2008). Adult attachment, sexual satisfaction, and relationship satisfaction: A study of married couples. Personal Relationships, 15, 141-154. ↵

- Campbell, L., Simpson, J. A., Boldry, J., & Kashy, D. A. (2005). Perceptions of conflict and support in romantic relationships: The role of attachment anxiety. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88, 510-532. ↵

- Simpson, J. A., Rholes, W. S., Oriña, M. M., & Grich, J. (2002). Working models of attachment, support giving, and support seeking in a stressful situation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28, 598-608. ↵

- Chopik, W. J., Edelstein, R. S., & Fraley, R. C. (2013). From the cradle to the grave: Age differences in attachment from early adulthood to old age. Journal or Personality, 81 (2), 171-183 DOI: 10.1111/j. 1467-6494.2012.00793 ↵

- Schindler, I., Fagundes, C. P., & Murdock, K. W. (2010). Predictors of romantic relationship formation: Attachment style, prior relationships, and dating goals. Personal Relationships, 17, 97-105. ↵

- Chopik, W. J., Edelstein, R. S., & Fraley, R. C. (2013). From the cradle to the grave: Age differences in attachment from early adulthood to old age. Journal or Personality, 81 (2), 171-183 DOI: 10.1111/j. 1467-6494.2012.00793 ↵

- Fraley, R. C. (2013). Attachment through the life course. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF publishers. Retrieved from nobaproject.com. ↵

- Chappell, K. D., & Davis, K. E. (1998). Attachment, partner choice, and perception of romantic partners: An experimental test of the attachment-security hypothesis. Personal Relationships, 5, 327–342. ↵

- Frazier, P. A, Byer, A. L., Fischer, A. R., Wright, D. M., & DeBord, K. A. (1996). Adult attachment style and partner choice: Correlational and experimental findings. Personal Relationships, 3, 117–136. ↵

- McClure, M. J., Lydon., J. E., Baccus, J., & Baldwin, M. W. (2010). A signal detection analysis of the anxiously attached at speed-dating: Being unpopular is only the first part of the problem. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36, 1024–1036. ↵

- Hudson, N. W., Fraley, R. C., Vicary, A. M., & Brumbaugh, C. C. (2012). Attachment coregulation: A longitudinal investigation of the coordination in romantic partners’ attachment styles. Manuscript under review. ↵

- Hazan, C., & Shaver, P. (1987). Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52 (3), 511-524. ↵

- Fraley, R. C., Roisman, G. I., Booth-LaForce, C., Owen, M. T., & Holland, A. S. (2013). Interpersonal and genetic origins of adult attachment styles: A longitudinal study from infancy to early adulthood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104, 8817-838. ↵

- Simpson, J. A., Collins, W. A., Tran, S., & Haydon, K. C. (2007). Attachment and the experience and expression of emotions in adult romantic relationships: A developmental perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92, 355–367. ↵

- Aquilino, W. S. (2006). Family relationships and support systems in emerging adulthood. In J. J. Arnett & J. L. Tanner (Eds.), Emerging adults in America: Coming of age in the 21st century (pp. 193-217). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. ↵

- Arnett, J. J. (2004). Conceptions of the transition to adulthood among emerging adults in American ethnic groups. In J. J. Arnett & N. Galambos (Eds.), Cultural conceptions of the transition to adulthood: New directions in child and adolescent development. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. ↵

- Aquilino, W. S. (2006). Family relationships and support systems in emerging adulthood. In J. J. Arnett & J. L. Tanner (Eds.), Emerging adults in America: Coming of age in the 21st century (pp. 193-217). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. ↵

- Aquilino, W. S. (2006). Family relationships and support systems in emerging adulthood. In J. J. Arnett & J. L. Tanner (Eds.), Emerging adults in America: Coming of age in the 21st century (pp. 193-217). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. ↵

- Dunn, J. (1984). Sibling studies and the developmental impact of critical incidents. In P.B. Baltes & O.G. Brim (Eds.), Life-span development and behavior (Vol 6). Orlando, FL: Academic Press. ↵

- Cicirelli, V. (2009). Sibling relationships, later life. In D. Carr (Ed.), Encyclopedia of the life course and human development. Boston, MA: Cengage. ↵

- Erikson, E. H. (1950). Childhood and society. New York: Norton. ↵

- Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. New York: Norton. ↵

- Hendrick, C., & Hendrick, S. S. (Eds.). (2000). Close relationships: A sourcebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. ↵