1940s: Skinner

OpenStax and Diana Lang

B.F. Skinner: Operant Conditioning

Psychologist B.F. Skinner saw that classical conditioning is limited to existing behaviors that are reflexively elicited, and doesn’t account for new behaviors such as riding a bike.[1] He proposed a theory about how such behaviors come about. Skinner believed that behavior is motivated by the consequences we receive for the behavior: reinforcements and punishments. His idea that learning is the result of consequences is based on the law of effect, which was first proposed by psychologist Edward Thorndike. According to the law of effect, behaviors that are followed by consequences that are satisfying to the organism are more likely to be repeated, and behaviors that are followed by unpleasant consequences are less likely to be repeated.[2] Essentially, if an organism does something that brings about a desired result, the organism is more likely to do it again. If an organism does something that does not bring about the desired result, the organism is less likely to do it again. An example of the law of effect is employment. One of the reasons (and often the main reason) we show up for work is because we get paid to do so. If we stop getting paid, we will likely stop showing up—even if we love our job.

| Classical Conditioning | Operant Conditioning | |

|---|---|---|

| Conditioning approach | An unconditioned stimulus (such as food) is paired with a neutral stimulus (such as a bell). The neutral stimulus eventually becomes the conditioned stimulus, which brings about the conditioned response (salivation). | The target behavior is followed by reinforcement or punishment to either strengthen or weaken it so that the learner is more likely to exhibit the desired behavior in the future. |

| Stimulus timing | The stimulus occurs immediately before the response. | The stimulus (either reinforcement or punishment) occurs soon after the response. |

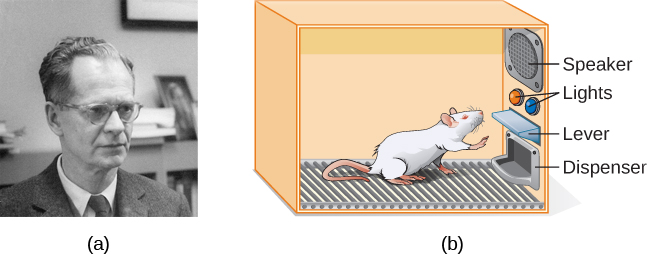

Working with Thorndike’s law of effect as his foundation, Skinner began conducting scientific experiments on animals (mainly rats and pigeons) to determine how organisms learn through operant conditioning.[3] He placed these animals inside an operant conditioning chamber, which has come to be known as a “Skinner box” (See Figure 1.). A Skinner box contains a lever (for rats) or disk (for pigeons) that the animal can press or peck for a food reward via the dispenser. Speakers and lights can be associated with certain behaviors. A recorder counts the number of responses made by the animal.

Watch this brief video clip to learn more about operant conditioning: Skinner is interviewed, and operant conditioning of pigeons is demonstrated.

In discussing operant conditioning, we use several everyday words—positive, negative, reinforcement, and punishment—in a specialized manner. In operant conditioning, positive and negative do not mean good and bad. Instead, positive means you are adding something, and negative means you are taking something away. Reinforcement means you are increasing a behavior, and punishment means you are decreasing a behavior. Reinforcement can be positive or negative, and punishment can also be positive or negative. All reinforcers (positive or negative) increase the likelihood of a behavioral response. All punishers (positive or negative) decrease the likelihood of a behavioral response. Now let us combine these four terms: positive reinforcement, negative reinforcement, positive punishment, and negative punishment (Table 2.).

| Reinforcement | Punishment | |

|---|---|---|

| Positive | Something is added to increase the likelihood of a behavior. | Something is added to decrease the likelihood of a behavior. |

| Negative | Something is removed to increase the likelihood of a behavior. | Something is removed to decrease the likelihood of a behavior. |

Reinforcement

The most effective way to teach a person or animal a new behavior is with positive reinforcement. In positive reinforcement, a desirable stimulus is added to increase a behavior.

For example, let’s say you tell your five-year-old son, Jerome, that if he cleans his room, he will get a toy. Jerome quickly cleans his room because he wants a new art set. Some people might say, “Why should I reward my child for doing what is expected?” However, we are constantly and consistently rewarded in our lives. Our paychecks are rewards, as are high grades or acceptance into our preferred schools. Being praised for doing a good job or for passing a driver’s test are also rewards. Positive reinforcement as a learning tool is extremely effective. It has been found that one of the most effective ways to increase achievement in school districts with below-average reading scores was to pay the children to read.

An example of this can be seen in Dallas, where second-grade students in Dallas were paid $2 each time they read a book and passed a short quiz about the book. The result was a significant increase in reading comprehension.[4] What do you think about this program? If Skinner were alive today, he would probably think this was a great idea. He was a strong proponent of using operant conditioning principles to influence students’ behavior at school. In fact, in addition to the Skinner box, he also invented what he called a teaching machine that was designed to reward small steps in learning—an early forerunner of computer-assisted learning.[5] His teaching machine tested students’ knowledge as they worked through various school subjects. If students answered questions correctly, they received immediate positive reinforcement and could continue; if they answered incorrectly, they did not receive any reinforcement. The idea was that students would spend additional time studying the material to increase their chance of being reinforced the next time.

In negative reinforcement, an undesirable stimulus is removed to increase a behavior. For example, car manufacturers use the principles of negative reinforcement in their seatbelt systems, which go “beep, beep, beep” until you fasten your seatbelt. The annoying sound stops when you exhibit the desired behavior, increasing the likelihood that you will buckle up in the future. Negative reinforcement is also used frequently in horse training. Riders apply pressure—by pulling the reins or squeezing their legs—and then remove the pressure when the horse performs the desired behavior, such as turning or speeding up. The pressure is the negative stimulus that the horse wants to remove.

Punishment

Many people confuse negative reinforcement with punishment in operant conditioning, but they are two very different concepts. Remember that reinforcement, even when it is negative, always increases a behavior. In contrast, punishment always decreases a behavior. In positive punishment, you add an undesirable stimulus to decrease a behavior. An example of positive punishment is reprimanding a student to get the student to stop texting in class. In this case, a stimulus (the reprimand) is added in order to decrease the behavior (texting in class). In negative punishment, you remove a pleasant stimulus to decrease a behavior, such as something the child enjoys (e.g., a toy or a scheduled outing). Time-outs are a very common form of negative punishment — they momentarily take away children’s access to something they enjoy.

Punishment, especially when it is immediate, is one way to decrease undesirable behavior. For example, imagine your four-year-old son, Brandon, runs into a busy street to get his ball. You give him a time-out (positive punishment) and tell him never to go into the street again. Chances are he will not repeat this behavior. While strategies like time-outs are common today, in the past children were often subject to physical punishment, such as spanking. It’s important to be aware of some of the drawbacks of using physical punishment on children. Within the context of parenting, it is important to note that the term “punishment” doesn’t mean that the consequence should be harmful.

In fact, experts caution that punishments like spanking can cause more harm than good. [6] First, punishment may teach fear. Brandon may become fearful of the street, but he also may become fearful of the person who delivered the punishment—you, his parent. Similarly, children who are punished by teachers may start to fear the teacher and try to avoid school.[7] Consequently, most schools in the United States have banned corporal punishment. Second, punishment may cause children to become more aggressive and prone to antisocial behavior and delinquency.[8] They see their parents resort to spanking when they become angry and frustrated, so, in turn, they may act out this same behavior when they become angry and frustrated. For example, because you spank Brenda when you are angry with her for her misbehavior, she might start hitting her friends when they will not share their toys.

While positive punishment can be effective in some cases, Skinner suggested that the use of punishment should be weighed against the possible negative effects. Today’s psychologists and parenting experts favor reinforcement over punishment—they recommend that you catch your child doing something good and reward her for it.

Shaping

In his operant conditioning experiments, Skinner often used an approach called shaping. Instead of rewarding only the target behavior, in shaping, we reward successive approximations of a target behavior. For instance, parents can break a task into smaller more “attainable” steps. These smaller steps should be in sequence of completing the entire desired task. As children start a step, or show improvements on a step, they should be praised and rewarded. As children master each step, they should again be praised and rewarded and then encouraged to the next step. This process of successive approximations is followed until a child masters the entire task. This takes time, but it is a proven method of shaping a child’s behavior via rewarding and praising ongoing improvements.

Why is shaping needed? Remember that in order for reinforcement to work, the organism must first display the behavior. Shaping is needed because it is extremely unlikely that an organism will display anything but the simplest of behaviors spontaneously. In shaping, behaviors are broken down into many small, achievable steps. The specific steps used in the process are the following:

- Reinforce any response that resembles the desired behavior.

- Then reinforce the response that more closely resembles the desired behavior. You will no longer reinforce the previously reinforced response.

- Next, begin to reinforce the response that even more closely resembles the desired behavior.

- Continue to reinforce closer and closer approximations of the desired behavior.

- Finally, only reinforce the desired behavior.

Shaping is often used to teach a complex behavior or chain of behaviors. Skinner used shaping to teach pigeons not only relatively simple behaviors such as pecking a disk in a Skinner box, but also many unusual and entertaining behaviors, such as turning in circles, walking in figure eights, and even playing ping pong; this technique is commonly used by animal trainers today. An important part of shaping is stimulus discrimination. Recall Pavlov’s dogs—he trained them to respond to the tone of a bell, and not to similar tones or sounds. This discrimination is also important in operant conditioning and in shaping behavior.

Here is a brief video of Skinner’s pigeons playing ping pong.

It is easy to see how shaping is effective in teaching behaviors to animals, but how does shaping work with humans? Let us consider parents whose goal is to have their child learn to clean his room. They use shaping to help him master steps toward the goal. Instead of performing the entire task, they set up these steps and reinforce each one. First, he cleans up one toy. Second, he cleans up five toys. Third, he chooses whether to pick up ten toys or put his books and clothes away. Fourth, he cleans up everything except two toys. Finally, he cleans his entire room.

Primary and Secondary Reinforcers

Rewards such as stickers, praise, money, toys, and more can be used to reinforce learning. Let us go back to Skinner’s rats again. How did the rats learn to press the lever in the Skinner box? They were rewarded with food each time they pressed the lever. For animals, food would be an obvious reinforcer.

What would be a good reinforcer for humans? For your daughter Sydney, it was the promise of a toy if she cleaned her room. How about Joaquin, the soccer player? If you gave Joaquin a piece of candy every time he made a goal, you would be using a primary reinforcer. Primary reinforcers are reinforcers that have innate reinforcing qualities. These kinds of reinforcers are not learned. Water, food, sleep, shelter, sex, and touch, among others, are primary reinforcers. Pleasure is also a primary reinforcer. Organisms do not lose their drive for these things. For most people, jumping in a cool lake on a very hot day would be reinforcing and the cool lake would be innately reinforcing—the water would cool the person off (a physical need), as well as provide pleasure.

A secondary reinforcer has no inherent value and only has reinforcing qualities when linked with a primary reinforcer. Praise, linked to affection, is one example of a secondary reinforcer, such as when you called out “Great shot!” every time Joaquin made a goal. Another example, money, is only worth something when you can use it to buy other things—either things that satisfy basic needs (food, water, shelter—all primary reinforcers) or other secondary reinforcers. If you were on a remote island in the middle of the Pacific Ocean and you had stacks of money, the money would not be useful if you could not spend it. What about the stickers on the behavior chart? They also are secondary reinforcers.

Sometimes, instead of stickers on a sticker chart, a token is used. Tokens, which are also secondary reinforcers, can then be traded in for rewards and prizes. Entire behavior management systems, known as token economies, are built around the use of these kinds of token reinforcers. Token economies have been found to be very effective at modifying behavior in a variety of settings such as schools, prisons, and mental hospitals.

Everyday Connection: Behavior Modification in Children

Parents and teachers often use behavior modification to change a child’s behavior. Behavior modification uses the principles of operant conditioning to accomplish behavior change so that undesirable behaviors are switched out for more socially acceptable ones. Some teachers and parents create a sticker chart, in which several behaviors are listed. Sticker charts are a form of token economies, as described in the text. Each time children perform the desired behavior, they get a sticker, and after a certain number of stickers, they get a prize, or reinforcer. The goal is to increase acceptable behaviors and decrease misbehavior. Remember, it is better to reinforce desired behaviors than to use punishment. In the classroom, the teacher can reinforce a wide range of behaviors, from students raising their hands, to walking quietly in the hall, to turning in their homework. At home, parents might create a behavior chart that rewards children for things such as putting away toys, brushing their teeth, and helping with dinner. In order for behavior modification to be effective, the reinforcement must be connected with the behavior, the reinforcement must matter to the child, and the process must be performed consistently over time.

Time-out is another popular technique used in behavior modification with children. When a child demonstrates an undesirable behavior, she is removed from the desirable activity at hand. For example, say that Sophia and her brother Mario are playing with building blocks. Sophia throws some blocks at her brother, so you give her a warning that she will go to time-out if she does it again. A few minutes later, she throws more blocks at Mario. You remove Sophia from the room for a few minutes. When she comes back, she doesn’t throw blocks.

There are several important points to consider if you plan to implement time-out as a behavior modification technique. First, make sure the child is being removed from a desirable activity and placed in a less desirable location. If the activity is something undesirable for the child, this technique will backfire because it is more enjoyable for the child to be removed from the activity. Second, the length of the time-out is important. The general rule of thumb is one minute for each year of the child’s age. Sophia is five; therefore, she sits in time-out for five minutes. Setting a timer helps children know how long they have to sit in time-out. Third, using this method should be dependent upon the child’s cognitive and social development, not merely the child’s chronological age. Finally, as a caregiver, keep several guidelines in mind over the course of a time-out: remain calm when directing your child to time-out; ignore your child during time-out (because caregiver attention may reinforce misbehavior), and give the child a hug or a kind word when the time-out is over.

Reinforcement Schedules

Remember, the best way to teach a person or animal a behavior is to use positive reinforcement. For example, Skinner used positive reinforcement to teach rats to press a lever in a Skinner box. At first, the rat might randomly hit the lever while exploring the box, and out would come a pellet of food. After eating the pellet, what do you think the hungry rat did next? It hit the lever again and received another pellet of food. Each time the rat hit the lever, a pellet of food came out. When an organism receives a reinforcer each time it displays a behavior, it is called continuous reinforcement. This reinforcement schedule is the quickest way to teach someone a behavior, and it is especially effective in training a new behavior. Let’s look at a dog learning to sit. Each time the dog sits, you give the dog a treat. Timing is important here: you will be most successful if you present the reinforcer immediately after the dog sits so that the dog can make an association between the target behavior (sitting) and the reinforcement (getting a treat).

Watch this video clip of veterinarian Dr. Sophia Yin shaping a dog’s behavior using the steps outlined above.

- Behavior is motivated by the consequences of that behavior.

- Behaviors with satisfying consequences are often repeated, while behaviors with unpleasant consequences are often avoided.

- Conditioning can be done through positive reinforcement, negative reinforcement, positive punishment, and negative punishment.

- Reinforcement increases a behavior; punishment decreases a behavior.

- Shaping is slowly reinforcing behaviors that are more and more similar to the ideal goal behavior.

- This chapter was adapted from OpenStax Psychology, and is used under a CC BY 4.0 license. Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/4abf04bf-93a0-45c3-9cbc-2cefd46e68cc@12.2. ↵

- Thorndike, E. L. (1911). Animal intelligence: Experimental studies. Macmillan Company. ↵

- Skinner, B. F. (1938). Behavior of organisms. Appleton-Century-Crofts. ↵

- Fryer, R. G. Jr. (2010). Financial incentive and student achievement: Evidence from randomized trials. National Bureau of Economic Research. Working Paper No. 15898. DOI 10.3386/w15898 ↵

- Skinner, B. F. (1961). Teaching machines. Scientific American, 205(3), 90-112. https://doi.org/10.2307/1926170. ↵

- Murphy, R. (2017). What is ‘negative punishment’? Definition and real-world examples. https://www.care.com/c/stories/11980/what-is-negative-punishment-definition-and-real-world-examples/. ↵

- Gerschoff, E. T. (2013). Spanking and child development: We know enough now to stop hitting our children. Child Development Perspectives, 7(3), 133-137. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12038 ↵

- Gershoff, E. T. (2002). Corporal punishment by parents and associated child behaviors and experiences: A meta-analytic and theoretical review. Psychological Bulletin, 128(4), 539–579. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.128.4.539 ↵

The notion that a behavior that is followed by consequences satisfying to the organism will be repeated and behaviors that are followed by unpleasant consequences will be discouraged.

A form of learning in which the stimulus/experience happens after the behavior is demonstrated.

Implementation of a consequence in order to increase a behavior.

Adding a desirable stimulus to increase a behavior.

Taking away an undesirable stimulus to increase a behavior.

Implementation of a consequence in order to decrease a behavior.

Adding an undesirable stimulus to stop or decrease a behavior.

Taking away a pleasant stimulus to decrease or stop a behavior.

Rewarding successive approximations toward a target behavior.

A reinforcer which has innate/inborn/instinctual reinforcing qualities (e.g., food, water, shelter, sex).

A reinforcer which has no inherent value unto itself and only has reinforcing qualities when linked with something else (e.g., money, gold stars, poker chips).

Rewarding a behavior every time it occurs.