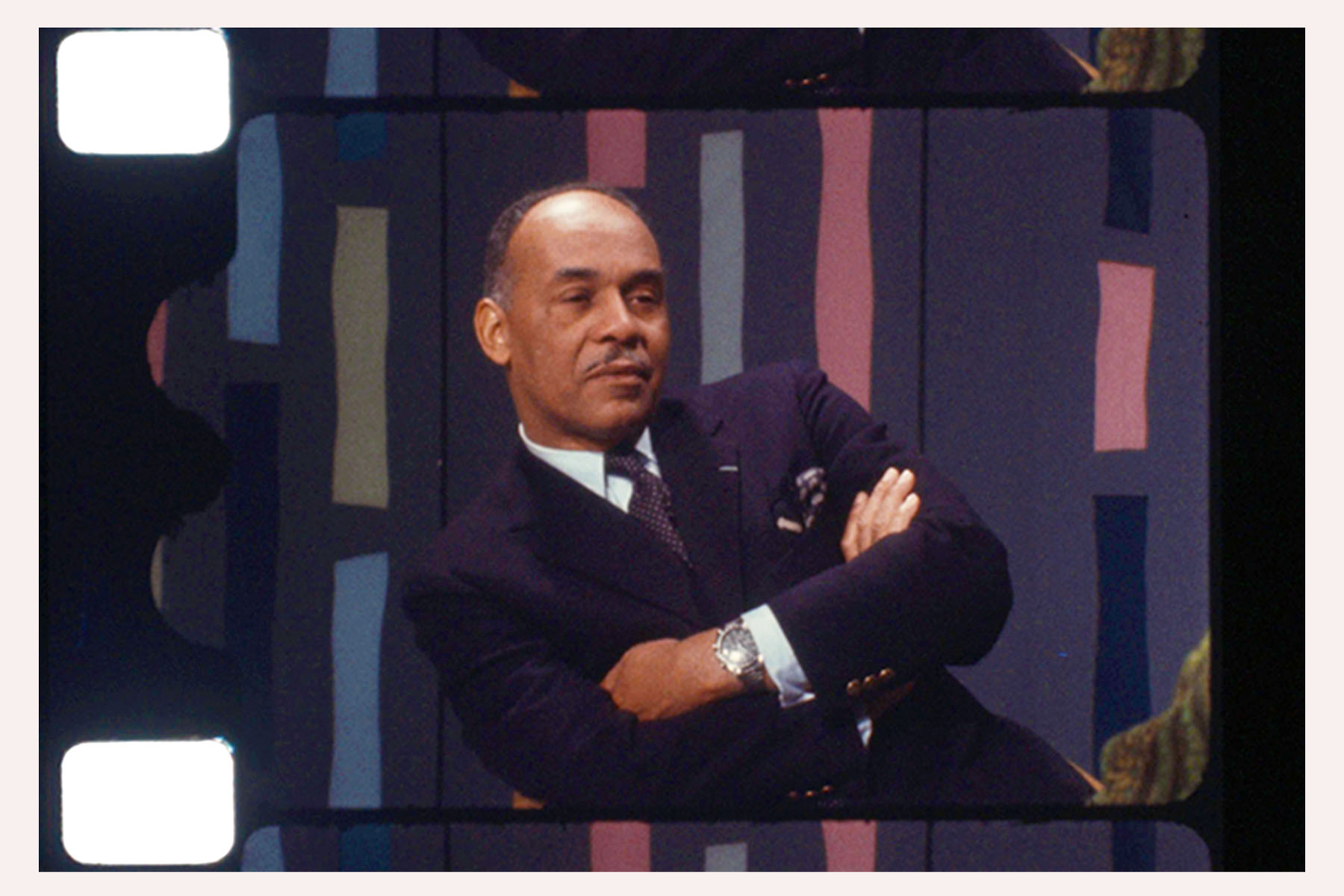

Ralph Ellison, Film, Jazz, and Cultural Memory Gaps

Rosie Rowe

On 18 March 1970, Ralph Ellison spoke at Iowa State University as part of the University’s Lecture Series program. Mr. Ellison was a 20th-century, African American author, whose first and only novel, Invisible Man, won the National Book Award. In spite of his renown, the lecture was not recorded (or, if it was, apparently did not survive). Nor have I been able to locate any documentation about his lecture. I’m left wondering how he would have engaged with the Iowa State audience. I wonder whether he spoke about his love of jazz and how music influenced his writing.

Charles ‘Buddy’ Bolden (1877–1931) was a well-known, African American coronet player and a progenitor of the jazz movement in New Orleans. His trombonist claimed that at least one cylinder phonograph was made of Bolden’s music at the turn of the century by a local New Orleans saloon owner, but no known recordings have survived. Major music industry labels—Edison, Columbia, and the Berliner—regularly paid white artists to record Black music. In fact, the earliest known jazz recording is a 1917 album by the Original Dixieland Jazz Band, an all-white group. So, despite its apparent uniqueness, labeling the Original Dixieland Jazz Band recording as a foundational document of jazz would be a misrepresentation of American history. In doing so, we would be ignoring the racism of the music industry that refused to record Black musicians and erasing the people and communities who were the actual creators of this American art form.

The loss of early jazz recordings—probably through neglect and mishandling—is one of the greatest examples we have of a cultural memory gap.

Cultural memory gaps within memory institutions are why modern archiving practices are slowly shifting toward intentionally collecting and prioritizing records of marginalized communities. This is why Black Archives, and other archives focused on marginalized communities, are so important. But we shouldn’t rely solely on these dedicated institutions to do ALL the collecting, prioritizing, and describing of these records. All archives must be responsible for hiring staff that can properly identify and interpret the records of marginalized communities. And as archivists, all of us share in the responsibility of preserving them.

Film and audio-visual (AV) records already have notoriously patchy documentation. What records have been collected have often not been effectively described. Combine that inherent lack of information with institutional and societal-level systems that, whether intentionally or unintentionally, erase the work of marginalized groups, and we are left with a huge cultural memory gap. We have little film and sound recordings from marginalized communities at Iowa State.

The scarcity of these records makes the ones that we do have even more valuable. I happened upon one of those valuable records while wrangling the Iowa State University Film Collections.

What we do know about Ralph Ellison’s visit to Iowa State is that Dorcas Speer, a WOI TV reporter, interviewed him before his lecture. That the interview was filmed, and that I was able to find it. This footage is from the WOI Radio and Television collection. We are working towards making WOI TV’s film collection more discoverable for researchers in the near future.

About this entry

Original Post: Ralph Ellison, Film, Jazz, and Cultural Memory Gaps

Publication Date: February 22, 2018

References

- Ellison, Ralph. The Invisible Man. Random House, 1952.

- The Black Film Center/Archive. Indiana University Bloomington. https://bfca.sitehost.iu.edu/home/.

- Iowa State University, WOI Radio and Television records, RS 5/6, Iowa State University Library Special Collections and University Archives.

- Original Dixieland Jazz Band. Livery Stable Blues, Victor, 1917.