The Booker T. Washington—W.E.B. Du Bois Debate

Amy Bishop

- Booker T Washington. Portrait from the first edition of The Negro Problem.

- Portrait of W.E.B. Du Bois from the first edition of The Negro Problem.

It is the turn of the 20th century. The Civil War is almost 40 years in the past, and Jim Crow laws are passed in Southern states to enforce racial segregation, while Black Americans encounter racism and discrimination across the country. A debate is going on within the Black community about how to respond to these conditions.

Booker T. Washington and vocational education

In 1895, Black intellectual and educator Booker T. Washington gave a speech at the Cotton States and International Exposition in Atlanta, Georgia, in which he urged Black Americans to temporarily accept segregation and disenfranchisement in exchange for economic opportunity and free vocational education funded by the white community. He believed that if Black men trained for vocational jobs, they could take advantage of the technological developments of the day and make economic progress. By attaining economic independence through hard work, thrift, and patience, he believed that eventually Black Americans would win the acceptance of the white community and thus be granted full civil rights. Critics of Washington’s speech dubbed it the ‘Atlanta Compromise.’

Washington’s speech was not published (though you can read the transcript at the Library of Congress), but his views on education for Black men (remember, this was at a time when a woman’s place was considered to be in the home) are captured in his essay, “Industrial Education for the Negro,” published in The Negro Problem in 1903. He writes that, following the Civil War, Black Americans tried to distance themselves from their past as enslaved people through higher education in the liberal arts:

There were young men educated in foreign tongues, but few in carpentry or in mechanical or architectural drawing. Many were trained in Latin, but few as engineers and blacksmiths. Too many were taken from the farm and educated, but educated in everything but farming. For this reason they had no interest in farming and did not return to it. And yet eighty-five per cent of the Negro population of the Southern states lives and for a considerable time will continue to live in the country districts (p. 13).

He saw the loss of vocational knowledge as a loss of economic opportunity to the population, and he believed that a purely liberal education only prepared Black men for jobs that they had no opportunity to acquire. This guided his decisions as the head of the Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute, now Tuskegee University, in designing the curriculum:

Almost from the first Tuskegee has kept in mind—and this I think should be the policy of all industrial schools—fitting student for occupations which would be open to them in their home communities (pp. 23–24).

Critiques by W.E.B. Du Bois

On the opposite side of the debate is W.E.B. Du Bois, a Black intellectual who was born and raised in Massachusetts and became the first Black man to earn a Ph.D. from Harvard University. Where Washington advised patience and submission, Du Bois called on members of the Black community to agitate for civil rights. He also argued that higher education, not simply vocational education, was necessary to create Black leaders that would uplift the whole Black community.

Du Bois was Washington’s most outspoken critic. His essay, “The Talented Tenth,” follows Washington’s in The Negro Problem. In direct rebuttal to Washington’s contention that liberally educated Black men cannot find jobs they are qualified for, Du Bois writes:

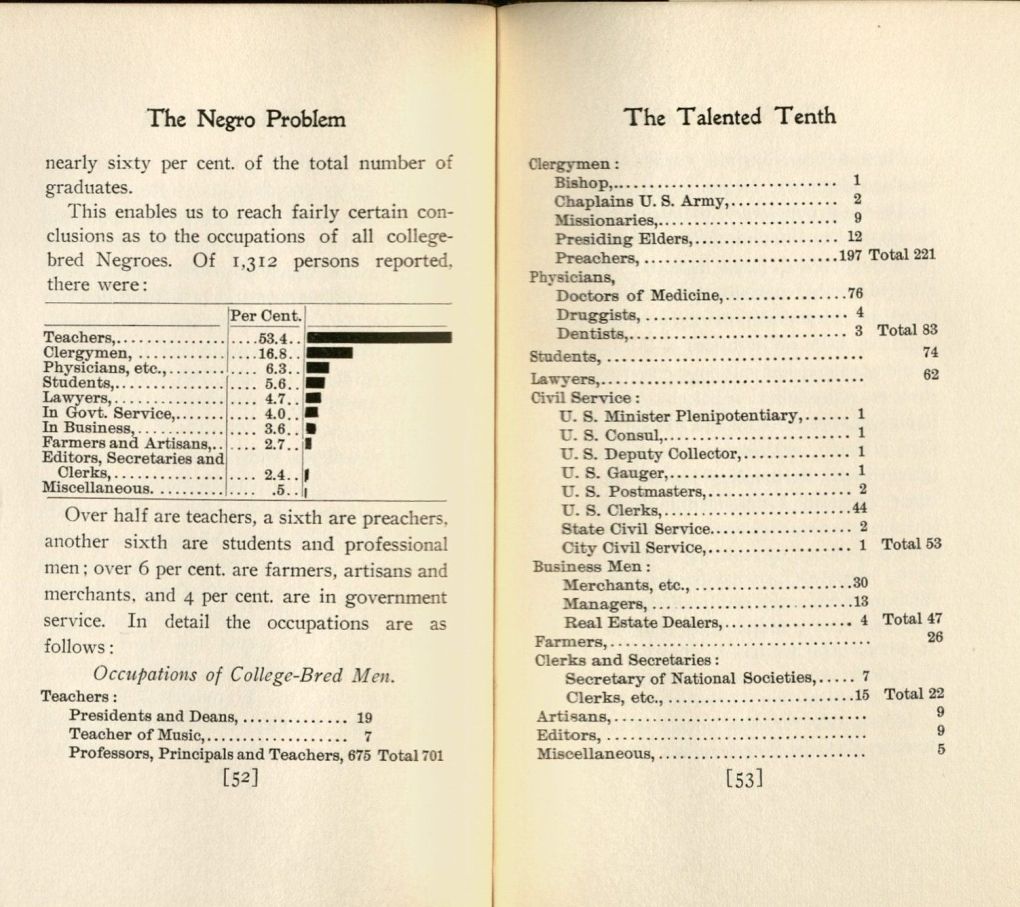

The most interesting question, and in many respects the crucial question, to be asked concerning college-bred Negroes, is: Do they earn a living? It has been intimated more than once that the higher training of Negroes has resulted in sending into the world of work, men who could find nothing to do suitable to their talents. Now and then there comes a rumor of a colored college man working at menial service, etc. Fortunately, returns as to occupations of college-bred Negroes, gathered by the Atlanta conference, are quite full—nearly sixty per cent. of the total number of graduates (pp. 51–52).

Du Bois’s most famous book The Souls of Black Folk, a collection of fourteen essays, includes one with the title, “Of Mr. Booker T. Washington and Others.” He critiques Washington’s broader plan of white appeasement and the regression it has brought:

Mr. Washington distinctly asks that black people give up, at least for the present, three things, —

First, political power,

Second, insistence on civil rights,

Third, higher education of Negro youth,—and concentrate all their energies on industrial education, the accumulation of wealth, and the conciliation of the South. This policy has been courageously and insistently advocated for over fifteen years, and has been triumphant for perhaps ten years. As a result of this tender of the palm-branch, what has been the return? In these years there have occurred:

1. The disfranchisement of the Negro.

2. The legal creation of a distinct status of civil inferiority for the Negro.

3. The steady withdrawal of aid from institutions for the higher training of the Negro (p. 51).

Both men were deeply concerned about the social and economic progress of Black Americans. Their backgrounds shed some light on the sharp differences in their approaches. Booker T. Washington was born into slavery in 1856 and taught himself to read as a child following the Civil War. Later, he worked his way through Hampton Normal Agricultural Institute in Virginia, now Hampton University. Du Bois, on the other hand, was born in 1868 in Massachusetts, where he attended school in a primarily white community. He attended Fisk University in Nashville, where he first encountered Jim Crow laws. Later, he became a leader in the Niagara Movement, a Black civil rights organization. When the group dissolved in 1909, Du Bois went on to co-found the NAACP.

What strikes me the most, as I write this blog post, is that the concerns of Washington and Du Bois are still relevant today. In the age of #BlackLivesMatter, this statement from Du Bois’s The Souls of Black Folk stands as a challenge and call to action:

…the burden belongs to the nation, and the hands of none of us are clean if we bend not our energies to righting these great wrongs (p.59).

About this entry

Original Post: Rare Book Highlights: the Booker T. Washington – W.E.B. Du Bois Debate

Publication Date: February 13, 2018

References

- Du Bois, W.E.B. The souls of black folk; essays and sketches. Chicago, A.C. McClurg & Co., 1903.

- Washington, Booker T., et al. The Negro problem; a series of articles by representative American Negroes of today. New York, James Pott & Company, 1903.