Mythical Creatures in Zoological Works

Amy Bishop

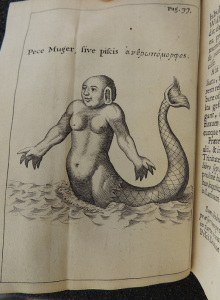

You know that feeling when you are flipping through an early book of natural history and you see illustrations of insects, armadillos, and…mermaids? No? Just me?

Truly, you never know what you are going to find when you look through early works of zoology. Mythical creatures aren’t limited to medieval bestiaries. Check out these other interesting creatures from books in our collections.

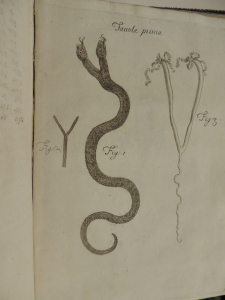

This two-headed snake-like creature is found in an Italian book on parasites from 1684.

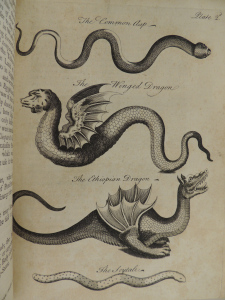

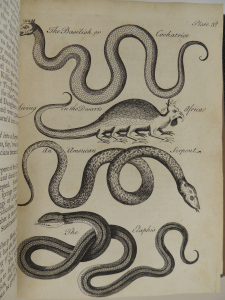

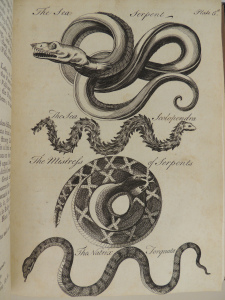

And for the Potterheads out there, Charles Owen’s An Essay Towards a Natural History of Serpents (1742) has many delights.

Winged dragons…

a basilisk…

and various sea serpents.

Owen has interesting things to say about all these serpents. Speaking of dragons, he cites ancient Greek and Roman historians who were said to have seen such beasts. The are supposed to be found in Europe, “between the Caspian and Euxine Sea,” as well as “the Atlantic Caves, and Mountains of Africa.” Surprisingly, “These also have been seen in Florida in America, where their Wings are more flaccid, and so weak, that they cannot soar on high” (192). “The Basilisk or Cockatrice,” he tells us, “is a Serpent of the Draconick Line, the Property of Africa, says Aelian, and denied by others: In shape, resembles a Cock, the Tail excepted” (78). He notes many traditional characteristics of the basilisk—again familiar to Potter fans: “his Eyes and Breath are killing,” “it goes half upright, the middle and posterior parts of the Body only touching the Ground,” and its venom “is said to be so exalted, that if it bites a Staff, ’twill kill the Person that makes use of it; but this is Tradition without a Voucher” (78–79).

Charles Owen (d. 1746), a Presbyterian minister, was following in the footsteps of the authors of early medieval bestiaries, who believed that animals as creatures created by God, were endowed with moral meaning for mankind. Thus, not being a scientist himself, he gathers together what others, particularly the ancient Greek and Roman authors, have written about the creatures and hopes that it “produces in the Reader a more exquisite Perception of God in all his Works” (vii). It comes as no surprise, then, that Owen frequently quotes from the Bible and refers to stories in which serpents play a role, or philosophizes on the symbolism of the serpent as with this passage from his section on dragons:

What is moral Evil but the Venom of the old Serpent? A Venom as pleasant to the Taste, as the forbidden Fruit to the Eye, but the End is Bitterness. And what are Incentives to Sin, but delusive Insinuations of the subtle Serpent? And what is Enjoyment, but a pleasing Illusion, which is no sooner grasp’d, but glides away as a Shadow, leaving behind it a wounded Conscience, direful Apprehensions and Prospects (193).

About this entry

Original Post: Rare Book Highlights: Mythical creatures in zoological works

Publication date: November 27, 2018

References

- Owen, Charles. An essay towards a natural history of serpents. London: Printed for the author, 1742.

- Redi, Francesco. Opuscula… Amsterdam, Apud Henricum Wetstenium, 1685-86.

- Redi, Francesco. Osservazioni di Francesco Redi … intorno agli animali viventi che si trovano negli animali viventi. Florence: P. Matini, 1684.