Labor and Birth

Labor and Birth

Labor involves the continuous dilation of the cervix accompanied by contractions over several different stages. Usually, labor comes at the end of a woman’s third term of pregnancy; however, under certain circumstances, it may come earlier. The form and fashion that labor occurs in is not universal to every person. Some mothers will give birth naturally, and others will undergo a cesarean birth. In addition, some mothers will opt for medicine to reduce pain during pregnancy while others will not. We will be discussing the following: signs of labor, hormones of labor, stages of labor, natural versus cesarean birth, medications and tools used during labor, and complications associated with labor and birth.

Signs of Labor

There are several indications of the onset of labor. These signs are mainly observed in the cervix, abdomen, and vagina. Some of these signs are commonly known such as “water breaking” and Braxton Hicks contractions, but there are several other more subtle signs. Here, we will go through each of the most common signs that labor is imminent.

Lightening

Lightening is the process of the baby moving inferiorly, or deeper, into the pelvis. The time at which this happens varies between individuals. For instance, in those that are having their first child, lightening can occur several weeks or just a few hours before labor. Conversely, in those that have already had a child, lightening occurs very close to labor. Indications of lightening are increased pressure in the pelvis, increased frequency of urination, and decreased shortness of breath.

Braxton Hicks

Braxton Hicks contractions do not indicate that labor is imminent. In fact, Braxton Hicks are known as “false labor pains.” Braxton Hicks do not come at a regular pace but are somewhat sporadic. They also do not cause dilation of the cervix like true contractions do.

Rupture of Membranes (ROM)

Rupture of Membranes is the technical phrase for saying that a mother’s water has broken. The phrase “water has broken” means that the amniotic sac has ruptured, releasing fluid and indicating that labor is imminent. Not all women experience this the same. Some experience a burst of water, and others have a slow stream or trickle. Once a mother’s water has broken, it is important that she immediately go to the hospital to minimize the risk of infection.

Cervical Changes

The cervix undergoes several changes to get ready for delivery through the birthing canal. These changes include ripening, effacement, and dilation. Ripening is cervical softening, effacement is cervical thinning, and dilation is cervical opening. Dilation is a term commonly heard throughout pregnancy as the doctor measures the amount of dilation to the cervix over time until full dilation has been reached and it is time to deliver.

Additional Signs

There are several additional signs of labor. For instance, vaginal discharge tends to thicken as labor nears. This is due to the mucous plug from the cervix getting displaced into the vaginal canal, and is often an indication that the cervix is starting to dilate. Sometimes, there is some blood in this discharge, which is common. Another sign of labor is nesting, a set of behaviors from the mother that involve an excess need to organize, clean, and prepare everything before the baby arrives. Additionally, a slight drop in weight can signal labor.

Hormones of Labor

There are several hormones involved in the onset of labor. Here, we will go through each of the hormones and what purpose they serve. Corticoptropin-Releasing Hormone (CHR) is a hormone released from the hypothalamus during labor stress that supports the development of the hormone Corticotropin (ACTH). ACTH is produced by the pituitary gland, and stimulates cortisol production by the adrenal glands, which leads to the release of estrogen that prepares the mother for childbirth. DHEA-sulfate, which is a steroid, comes into play in the last stage of pregnancy as an estrogen substrate.

Other more common hormones that come into play in preparation for labor are estrogen, progesterone, and prostaglandins. Estrogen is produced by the ovaries and fetal placenta. It helps to soften the cervix in preparation for dilation, and is involved in the manufacture of prostaglandins that participate in uterine muscle contraction. Progesterone is produced by the placenta and inhibits uterine contractions. A significant drop in progesterone during pregnancy is what initiates labor at the placental site by no longer inhibiting uterine contractions.

The ratio of estrogen to progesterone is important during labor. Prostaglandins are produced by tissue cells, and their main function is to help promote labor by stimulating the uterus muscle to contract. Fetal cortisol levels are also important, as they stimulate the production of enzymes that help regulate the development of placental alternatives, such as the lungs and liver, after birth.[1]

Lastly, oxytocin is a hormone produced by the pituitary gland and placenta. Oxytocin release helps stimulate the contraction of the uterine muscles and increase prostaglandin release to further increase contractions and dilate the cervix. There are oxytocin receptors located in both the myometrium and parietal decidua of the uterus. There are several different types of oxytocin that play a role in labor: placental, pituitary, and synthetic. Labor initiation is assisted by placental oxytocin. Contractions and prostaglandin release are further coaxed by a physician when they administer synthetic oxytocin. Upon every contraction, pituitary oxytocin is released and assists in decreasing pain, anxiety, and stress in the person going through labor. In fact, this form of oxytocin stimulates the parasympathetic nervous system to offset the sympathetic nervous system during labor. Pituitary oxytocin also increases activity in the reward centers of the brain which produces feelings of pleasure.[2]

Stages of Labor

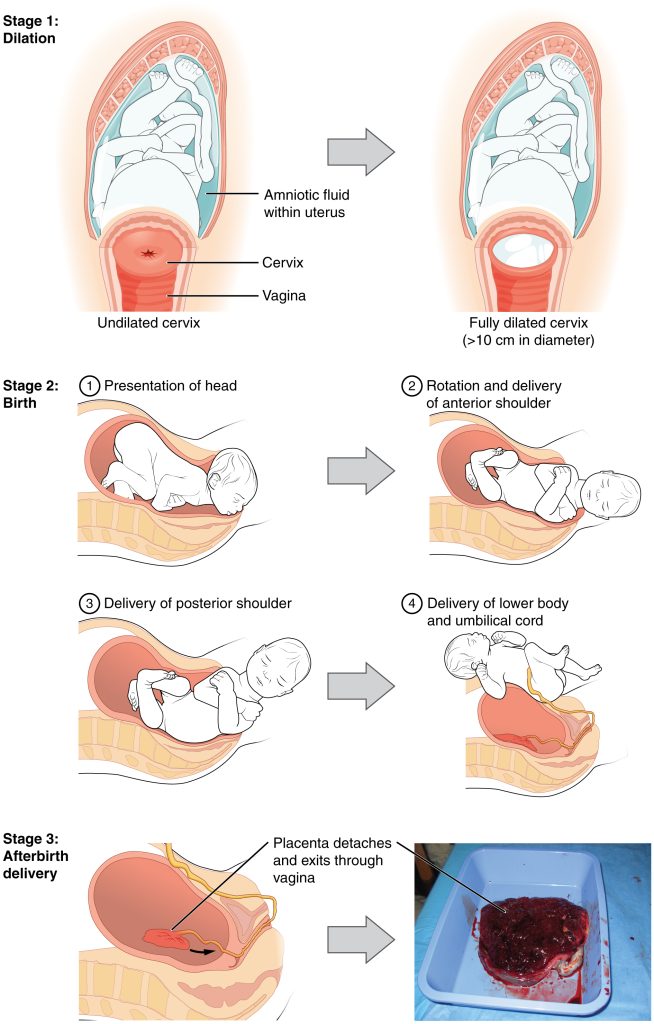

Stage 1: Cervical Effacement and Dilation

The first stage of labor is the longest, lasting approximately 20 hours for individuals who are giving birth for the first time and less than 14 hours for those who have given birth before. The first stage of labor is composed of two different phases: latent and active.

During the latent phase, the cervix dilates from 0 to 6 cm. During the active phase, the cervix dilates from 6 to 10 cm (full dilation). If there is a halt to cervical change or contractions after 4 or 6 hours respectively, this is a sign of labor complications.

Stage 2: Expulsion of the Fetus

The second stage of labor involves the process of the fetus exiting through the birthing canal. This stage can last approximately 2 hours for those who are giving birth for the first time or up to 30 minutes for those who have given birth before. During this stage, contractions typically last for 1 minute with 2 to 3 minute periods of relaxation in between. The baby will start to “crown” during this stage, with the head approaching the exterior of the birthing canal. Since the skull bones of the baby are not fused, their head may appear cone-shaped. In a normal birth, the baby’s head will be delivered first, followed by its shoulders. Once the shoulders pass through, the rest of the body should deliver easily as the shoulders are the widest part to pass through the birthing canal. Once the baby has been delivered, it will take its first breath or be stimulated to cry and take its first breath. In an uncomplicated delivery, the umbilical cord will be cut within minutes of delivery. If the delivery had complications, there will be a further assessment on whether or not to cut the umbilical cord right away.

Stage 3: Birthing of the Placenta

The third and final stage of labor involves the delivery of the placenta. This process usually takes no longer than 30 minutes to complete. If it takes longer than 30 minutes, there is an increased risk of hemorrhage. During this stage, oxytocin is still at work stimulating contractions of the uterus to get the placenta to detach and exit the birthing canal. There are several signs that the placental birthing process has started, and these include the elongation of the umbilical cord, fundus position, and a short increase in blood flow from vagina. Once the placenta has been birthed, there are several options for how it might be used. For example, the hemopoietic cells of the placenta might be used in cancer patients. It can also be frozen and used if the baby falls ill later on.

Different Types of Birth

Natural Birth

A natural birth is a birth through the vagina with no additional medical procedures. Natural birth can occur with or without medicine. Without medicine, breathing and relaxation techniques can be used to relax the mother as much as possible during labor. Medicine can also be used during a natural birth, such as an epidural, to reduce pain for the mother. There are several risks associated with a natural birth, which include but are not limited to tearing, infection, and loss of blood. There are additional risks in labor when an epidural is used, including infection, nerve damage, and seizures.

Cesarean Birth

An alternative to a natural birth is a cesarean birth (or c-section), which involves medical intervention via abdominal and uterine surgery to remove the baby from the womb. There are several reasons why a cesarean birth may be performed instead of a natural birth, including but not limited to unprogressive labor, baby in distress, abnormal baby positioning, multiple gestation birth, umbilical cord prolapse, placental issues, a previous c-section, or health concerns. Cesarean birth is a surgical procedure and it does have some more risk associated with it than a natural birth. This risk includes infection, clotting, blood loss (hemorrhage), and associated surgical injuries. However, cesarean births are not uncommon. In fact, in 2021, there were 1,174,545 deliveries via c-section and 2,486,856 deliveries via natural birth.[3]

Image Sources

- Figure 1. “Stages of Childbirth” is from OpenStax Anatomy & Physiology, licensed CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction

- Liggins, Graham Collingwood. “The Role of the Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal Axis in Preparing the Fetus for Birth.” American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, vol. 182, no. 2, Feb. 2000, pp. 475–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-9378(00)70241-9. ↵

- Dawood M.Y., Raghavan, K.S., Pociask, C., & Fuchs, F. "Oxytocin in human pregnancy and parturition." Obstet Gynecol. vol. 51, no. 2, Feb. 1978, pp. 138-43. PMID: 622223. ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Birth-Methods of delivery. National Center for Health Statistics. 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/delivery.htm ↵