Gametogenesis, Fertilization, and Implantation

Placenta Development

The placenta is a vital organ for fetal development. It arises from the trophoblastic layer of the blastocyst. At 14 days after fertilization, the cytotrophoblast, the trophoblast layer facing the fetal side, develops the chorion layer that wraps around the baby. The outer layer of the trophoblast, the syncytiotrophoblast, forms on the maternal side of the placenta.

The placenta gradually takes over the corpus luteum’s duties in the secretion of estrogen and progesterone. By the end of the first trimester, the placenta becomes the primary source of estrogen and progesterone and is responsible for the continuation of pregnancy, taking over the role of feeding the embryo.

The placenta usually connects to the conceptus via the umbilical cord, which contains the umbilical vessels. The spaces within the cord and around the blood vessels are filled with Wharton’s jelly, a mucous connective tissue. The umbilical cord and vessels aid in the transfer of oxygen, nutrients, and waste products without mixing maternal and fetal blood. Deoxygenated blood and waste leaves the fetus through two umbilical arteries, while nutrients and oxygen are carried from the mother to the fetus through a single umbilical vein. The umbilical cord is surrounded by the amnion. The placenta’s initial development as an organ is complete by weeks 14–16 after fertilization.

The placenta grows like an expanding disk. By week 20, the placenta covers half of the uterine wall and weighs about 200g. At term, it is about 700g and 20cm in diameter. The placenta is highly vascular and if the baby dies or is delivered, the placenta can keep growing.

Because blood cells cannot move across the placenta, the maternal and fetal blood do not co-mingle. This separation prevents the mother’s cytotoxic T cells from reaching and subsequently destroying the fetus, which bears “non-self” antigens. Further, it ensures the fetal red blood cells do not enter the mother’s circulation and trigger antibody development (if they carry “non-self” antigens) until the final stages of pregnancy or birth. This separation is why, even in the absence of preventive treatment, an Rh− mother doesn’t develop antibodies that could cause hemolytic disease in her first Rh+ fetus.

Although blood cells are not exchanged, the placenta is permeable to lipid-soluble fetotoxic substances: alcohol, nicotine, barbiturates, antibiotics, certain pathogens, and many other substances that can be dangerous or fatal to the developing embryo or fetus. For these reasons, pregnant women should avoid fetotoxic substances.

The placenta is normally attached and situated in the upper one-third of the anterior or posterior uterine wall within the endometrium. This placement is conducive to the growth and development of the embryo.

Clinical Correlation: Abnormal Attachment of the Placenta

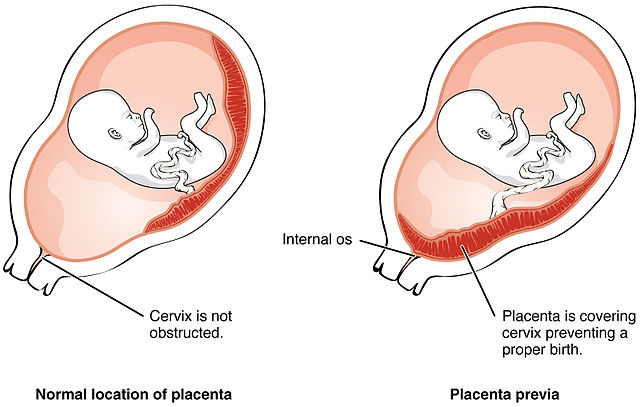

Placenta Previa

Implantation of the placenta occurs in the lower part of the uterus. A place can result in the partial or complete coverage of the cervical os. As the highly vascularized nature of the placenta, bleeding may occur with the growing uterus, and early or partial separation of the placenta may happen, and continuation of pregnancy will be jeopardy.

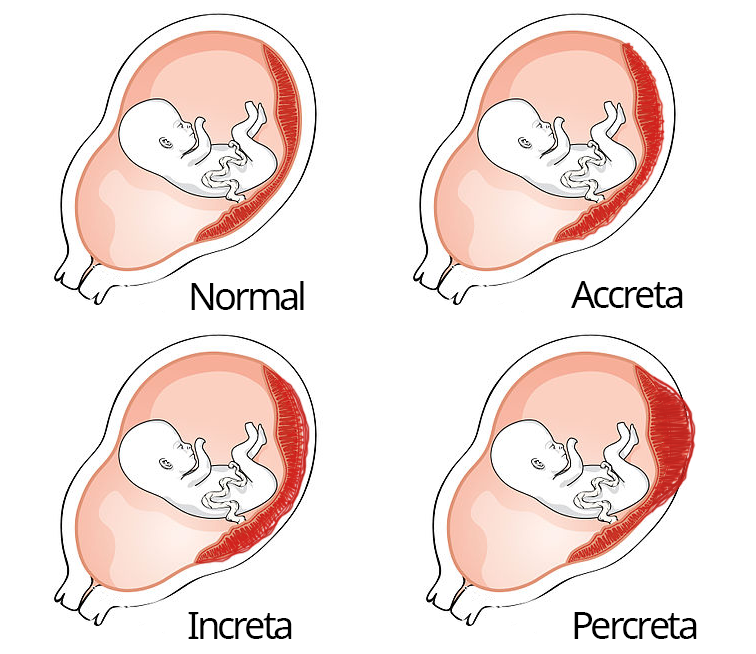

Placenta Accreta

A condition characterized by placenta attachment directly into the myometrium, placenta accreta is often caused by defective decidual endometrial layers, uterine inflammation, or old scar tissue from previous cesarean or uterine surgery. Tied placental implantation in the myometrium will impair placental separation after birth, resulting in massive bleeding and hemorrhage that may even lead to the death of the mother.

Take Home Message

- The placenta is a necessary organ for fetal growth.

- The placenta’s growth is independent of fetal growth.

- Attachment of placenta is typically in the upper 1/3 of the endometrium.

Image Sources

- Figure 1. “Placenta Previa” is from OpenStax Anatomy & Physiology 2E, licensed CC BY 4.0. Access for free at OpenStax Anatomy and Physiology 2E online.

- Figure 2. “Accreta, Increta, and Percreta placenta growth” is adapted by Abbey Elder from “Placenta Previa” in OpenStax Anatomy & Physiology 2E, licensed CC BY 4.0. Access for free at OpenStax Anatomy and Physiology 2E online.