The Male Reproductive System

Scrotum and Testes

The majority of the male reproductive system is external, located in the perineum region between the upper part of the two thighs. Male external genitalia include the scrotum, its contents, and the penis.

Scrotum

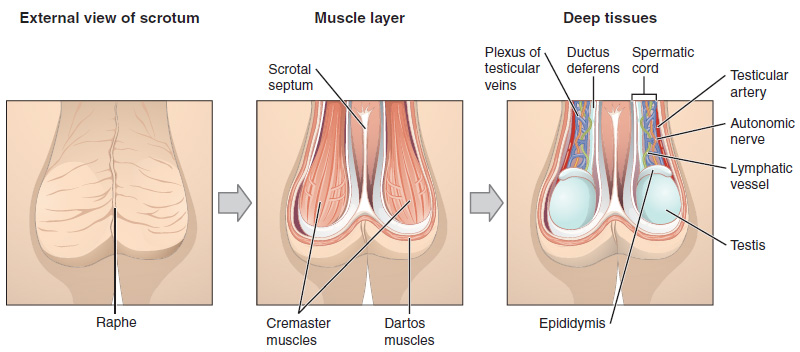

The scrotum is a skin-covered, highly-pigmented muscular sac containing the testes. The scrotum extends from the body behind the penis (Figure 1). This location is important in sperm production, which occurs within the testes and proceeds more efficiently when the testes are kept 2 to 4°C below core body temperature. The scrotum is homologous to the labia majora in the female during fetal development.

The dartos muscle is a subcutaneous smooth muscle that makes up the wall of the scrotum. It continues internally to make up the scrotal septum that divides the scrotum into two compartments, each housing one testis. Descending from the internal oblique muscle of the abdominal wall are the two cremaster muscles, which cover each testis like a muscular net. By contracting simultaneously, the dartos and cremaster muscles can elevate the testes in cold weather (or water), moving the testes closer to the body and decreasing the surface area of the scrotum to retain heat. Alternatively, as the environmental temperature increases, the scrotum relaxes, moving the testes farther from the body’s core and increasing the scrotal surface area, which promotes heat loss. Externally, the scrotum has a raised medial thickening on the surface called the raphae defines the separation between the two scrotal sacs.

Spermatic Cord

The spermatic cord is a cord-like structure in the male reproductive system that communicates between the abdominal cavity and scrotum and transmits to the testes and genital ducts. It consists of several parts:

- The extension of abdominal muscles forms the cremaster muscle and fascia that covers the spermatic cord.

- The testicular artery: a branch of the abdominal aorta to supply the testes.

- Pampiniform plexus: a network of veins surrounding the testicular artery and helps to counter current arterial heat and make sure the testes at cooler environment.

- The Autonomic nerves: fibers that supply the genitalia.

- Vas deference (Ductus deference): a duct that connects to the testis and carries sperm up to the ejaculatory duct in the pelvis.

Testes

The testes (singular = testis) are the male gonads, the primary sex organ in the male reproductive system. They produce both sperms, in addition to the production and secretion of androgens and the male sex hormone, testosterone. Testes are active throughout the reproductive lifespan of the male.

The testes are paired oval structures, each approximately 4 to 5 cm in length and housed within the scrotum. During fetal development, the testes develop as abdominal organs. In the seventh month of the developmental period, each testis moves to descend into the scrotal cavity. At birth, testes reach their final destination in the scrotal sacs. This process is called the “descent of the testis.”

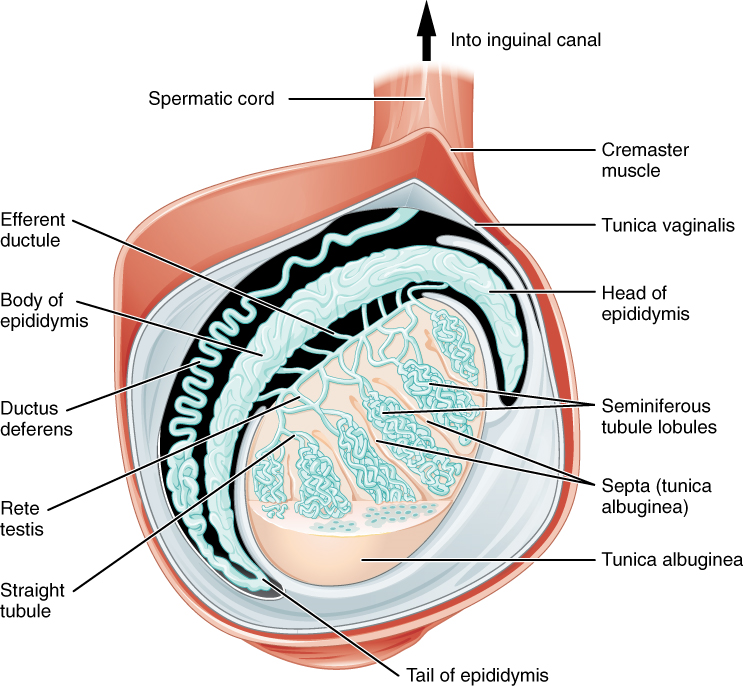

During their migration to the scrotum, the testes are enclosed in part by the peritoneum membrane. As they descend into the scrotum, the anterior and lateral surfaces of each testis remain covered by the peritoneal membrane, the tunica vaginalis layer, a serous membrane that has both a parietal and a thin visceral layer of the peritoneum (Figure 2).

Clinical Correlation

Cryptorchidism

Cryptorchidism is a clinical term used when one or both of the testes fail to descend into the scrotum prior to birth. Undescended testes will lead to male infertility and inability to produce sperms, as the testes require a cooler environment for the manufacture of sperms. It may also be associated with testicular tumors. Usually, testes descend during the first year of life on their own; however, to reduce the risk, it is much better to be brought into the scrotum in infancy by a surgical procedure called orchiopexy.

Hydrocele

Fluid accumulation between the two layers of tunica vaginalis leads to swelling of the scrotum, a condition known as hydrocele. It is a common condition in newborns and usually disappears without treatment by age 1. Transillumination, through shining a light through the scrotum, will show clear fluid surrounding the testes. A simple and easy diagnostic method to distinguish fluid accumulation from other causes of scrotum enlargement. Older boys and adult men can develop a hydrocele due to inflammation or injury within the scrotum.

Beneath the tunica vaginalis is the tunica albuginea, a tough, white, dense connective tissue layer covering the testis itself. Not only does the tunica albuginea cover the outside of the testis, but it also invaginates to form septa that divide the testis into lobes and lobules. Around 250 lobules are developed. Each lobule contains four convoluted seminiferous tubules, where sperms develop. In the posterior surface, Tunica albuginea projects deeper into the interior of the testis as the mediastinum testis, through which blood vessels, lymphatic vessels, and some nerves enter and leave the testis.

Seminiferous Tubules

The seminiferous tubules are the tightly coiled tubules that form the bulk of each testis. They are composed of two types of cells: the sperm developing Spermatogenic cells and the supporting cells known as Sustentacular cells (Figure 3).

Spermatogenic Cells

These are a population of dividing germ cells that continuously produce sperm beginning at puberty. Germ cells development progresses from the basement membrane at the perimeter of the seminiferous tubule toward its lumen.

The least mature cells, the spermatogonia (singular = spermatogonium), line the basement membrane inside the tubule. Spermatogonia are the stem cells of the testis, which means that they are still able to differentiate into a variety of different cell types throughout adulthood. Spermatogonia divide to produce primary and secondary spermatocytes, then spermatids, which produce formed sperm. The process that begins with spermatogonia and concludes with the production of sperm is called spermatogenesis.

The formed sperm are released into the duct system of the testis. Specifically, from the lumens of the seminiferous tubules to straight tubules (or tubuli recti), and from there into a fine meshwork of tubules called the rete testes. Sperms leave the rete testes, and the testis itself, through the 15 to 20 efferent ductules that cross the tunica albuginea.

Sustentacular (Sertoli Cells)

The elongated, pyramid-shaped, non-dividing supportive cells that surround all stages of the developing sperm cells are called Sustentacular or Sertoli cells. They extend physically around the germ cells from the peripheral basement membrane of the seminiferous tubules to the lumen. They provide support and nourishment to spermatogenic cells, and phagocytose the degenerating cells during spermatogenesis.

The sustentacular cells are connected by tight, form-occluding junctions, creating a diffusion barrier called the blood–testis barrier. The barrier maintains a luminal environment favorable for sperm maturation. It keeps bloodborne substances from reaching the germ cells and, at the same time, keeps surface antigens on developing germ cells from escaping into the bloodstream and prompting an autoimmune response.

Under the influence of FSH, Sertoli cells also function to secrete androgen-binding protein (ABP) that increases the concentration of testosterone within the seminiferous tubules and facilitates the process of spermatogenesis. They also secrete inhibin, a hormone that controls testosterone and sperm production at the higher brain centers.

Figure 3. Spermatogenic and Sertoli cells

Germinal epithelium of the testicle.

1. basal lamina

2. spermatogonia

3. primary (1st-order) spermatocyte

4. secondary (2nd-order) spermatocyte

5. developing spermatid

6. mature spermatid

7. Sertoli cell

8. tight junction (blood-testis barrier)

Interstitial Space

Between the seminiferous tubules, there is interstitial space and tissues. Within the interstitial tissue, interstitial cells, also known as Leydig cells, are located. Leydig cells, under the influence of LH hormones, get activated and secrete testosterone (androgenic hormone), the main male sex hormone. Testosterone circulates in the blood and, once reaches its target organs, stimulates puberty. It works on skeletal muscles, causing protein synthesis and muscle enlargement. It also stimulates Growth Hormone (GH) secretion, increasing bone growth in adolescence. Testosterone is responsible for the promotion and maintenance of secondary sex characteristics. In the brain, plasma testosterone increases the sex drive. Testosterone acts at Sertoli cells and stimulates spermatogenesis and sperms production. During fetal development, testosterone works at the Wolffian duct to promote the development of male reproductive structures.

Blood Vessels Around Testes

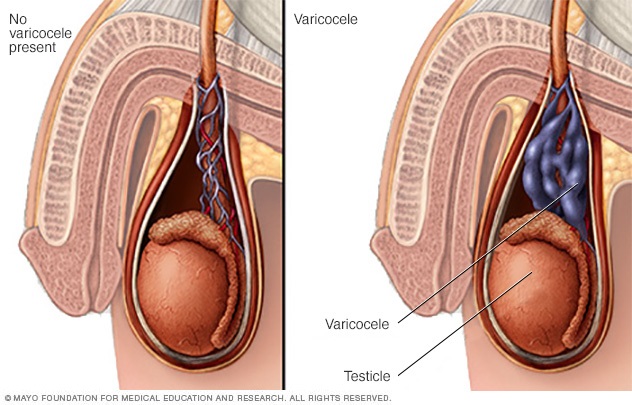

The testes get nourishment and oxygenated blood through the testicular artery, a direct branch of the abdominal aorta, as they develop as abdominal organs. In the spermatic cord, the testicular artery is surrounded by a group of veins, Pampiniform plexus, that drain waste and return deoxygenated blood back to the testicular vein in the abdomen (Figure 4). This pampiniform plexus reduces the temperature around the testes and works as a countercurrent heat-exchange system to cool down the arterial blood before it enters the testis.

Clinical Correlation

Varicocele

Varococoele are enlarged dilated pampiniform plexus veins that surround the testes. The veins feel like cords or worms within the scrotal sac and may be visible on the surface of scrotum. This may be caused by an upper venous drainage obstruction in the pelvis or abdomen, which leads to the stagnation of blood around the testes, impeding their heat-regulatory system and leaving the testes in a hot environment. Varicoceles cause low sperm production and decreased sperm quality, and are a common cause of male infertility (Figure 5).

Take Home Message

- The testes are kept cooler than core body temperature within the scrotum.

- Sperms synthetize within the somniferous tubules in the testes at the puberty.

- Leydig cells produce testosterone within the interstitial space, while Sartori cells stimulate its uptake within the seminiferous tubules and stimulate the process of spermatogenesis.

- The blood testes barrier favors sperm maturation and prevents contact with the immune system.

Image Sources

- Figure 1. “The Scrotum and Testes” is from OpenStax Anatomy & Physiology 2E, licensed CC BY 4.0. Access for free at OpenStax Anatomy and Physiology 2E online.

- Figure 2. “Anatomy of the Testis” is from OpenStax Anatomy & Physiology 2E, licensed CC BY 4.0. Access for free at OpenStax Anatomy and Physiology 2E online.

- Figure 3. “Germinal epithelium testicle” is from Uwe Gille via Wikimedia Commons, licensed CC BY SA 3.0.

- Figure 5. “Varicocele” is © Mayo Foundation. Used here as a thumbnail image for educational purposes under fair use.