The Female Reproductive System

Uterus and Uterine Cervix

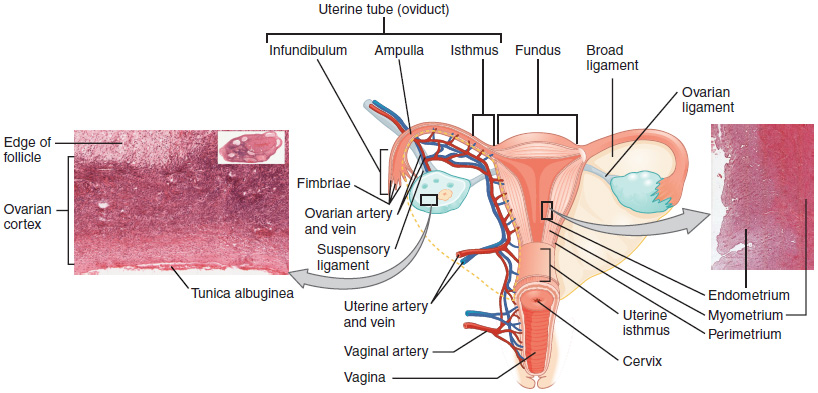

The uterus is a pear-shaped, thick-walled muscular organ within the pelvic cavity that nourishes and supports the growing embryo (Figure 1). Its average size is approximately 5 cm wide by 7 cm long (approximately 2 in by 3 in) when a female is not pregnant, and it possesses a lumen that is continuous with the uterine tubes.

Uterus has four sections. The portion of the uterus superior to the opening of the uterine tubes is called the fundus. The middle section of the uterus is called the body of the uterus (or corpus). The cervix is the narrow inferior portion of the uterus that projects into the vagina. The isthmus is a constricted segment 1 cm long between the body and cervix, which is the preferred site for surgical delivery by cesarean section.

Uterine position

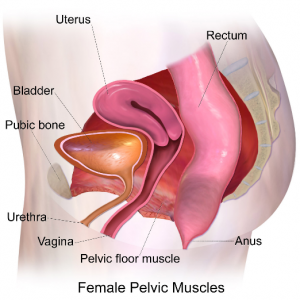

The uterus is normally located between the rectum and urinary bladder, superior to the vagina and angled antero-superior across the superior surface of the urinary bladder, a position referred to as anteverted (Figure 2).

Support of the Uterus

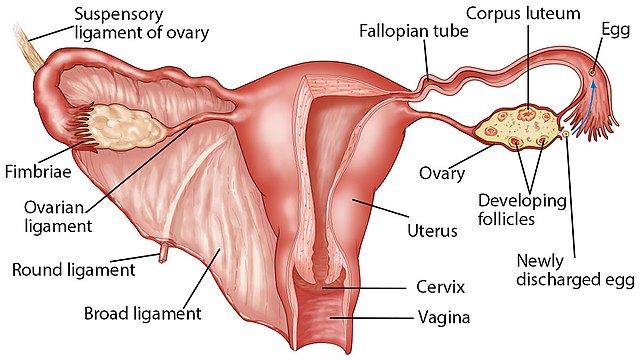

Several ligaments (Figure 3) maintain the position of the uterus position within the abdominopelvic cavity:

- The broad ligament, a fold of peritoneum, serves as a primary support for the uterus, extending laterally from both sides of the uterus and attaching it to the pelvic wall.

- The round ligament, a rope-like band of connective tissue, attaches to the uterus near the uterine tubes and extends to the labia majora.

- Transverse ligament (cardinal ligament), holds the cervical part of the uterus to the lateral pelvic wall. Uterine vessels run through the cardinal ligaments.

- Uterosacral ligament, stabilizes the uterus posteriorly by its connection from the cervix to the sacrum.

- The intact pelvic floor muscle, the Levator ani muscles, covers the external pelvis and holds the uterus in place to prevent it from dangling into the perineal region.

Clinical Correlation

Back Pain

During the menstrual cycle or growing fetus in pregnancy leads to pain in the lower back, usually referred to overstretch of the uterosacral ligament and increasing the pressure over the sacrum.

Retro-verted Uterus

When the uterus is tilted posteriorly toward the rectum instead of facing forward, this is called a retro-verted position. Individuals with a retro-verted uterus may not have any symptoms at all, or they may experience back pain during menstruation (Dysmenorrhea) or pain during sexual intercourse (Dyspareunia). Pregnancy could proceed normally; however, a retroverted uterus can be associated with infertility, though other possible causes of infertility should be ruled out first.

Uterine Prolapse

Weakness of the uterine support muscles and ligament may lead to protrusion of the uterus through the vagina, uterine prolapse (Figure 4). Prolapse may be mild with no symptoms, or it may lead to discomfort and severe symptoms that interfere with daily life.

Symptoms of uterine prolapse may include:

- A sensation of heaviness or pulling in the pelvis.

- Soft tissue protruding from the vagina.

- Urinary problems, such as urine leakage (incontinence) or urine retention.

- Trouble having a bowel movement.

- Feeling as if one is sitting on a small ball or as if something is falling out of the vagina.

- Sexual concerns, such as a sensation of looseness in the tone of one’s vaginal tissue.

Uterine Pouches

The peritoneal folds around the uterus and various pelvic organs lead to two major dead-end recesses or pouches. The Vesicouterine pouch, a space between the uterus and the urinary bladder, and the Rectouterine pouch or (Gouglas pouch), a space between the uterus and the rectum, the most dependent point where infection and fluid might be collected.

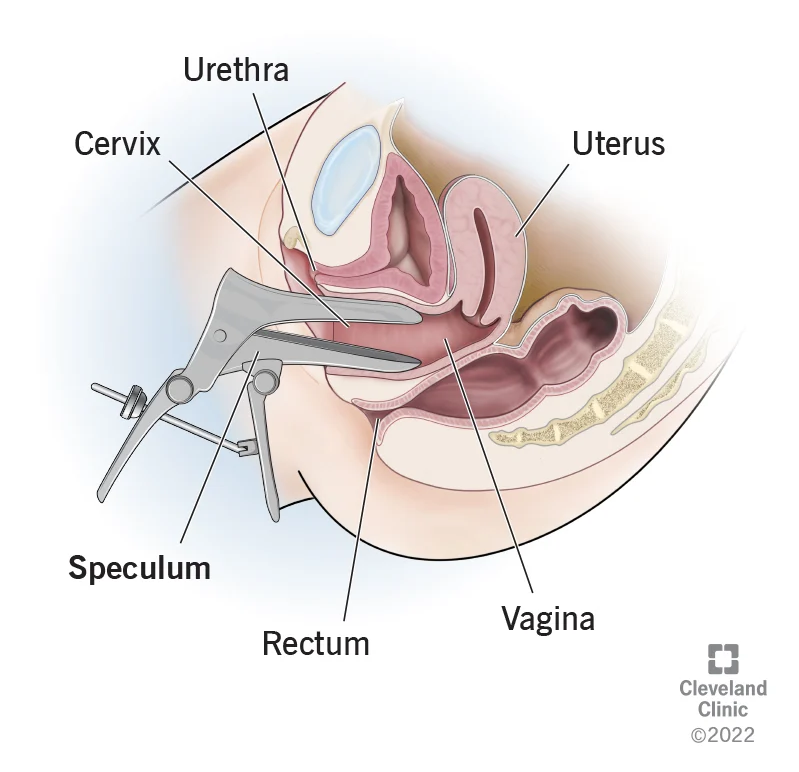

Culdocentesis (Figure 5) is the procedure in which peritoneal fluid is obtained from the female Rectouterine pouch.

This procedure involves the introduction of a needle to the posterior vaginal fornix wall to reach the Douglas pouch and aspirate the peritoneal fluid. Culdocentesis helps to collect, analyze fluid, and aid in clinical diagnosis.

The Uterine Wall

The wall of the uterus is made up of three layers (Figure 1). The most superficial layer is the serous membrane, or the perimetrium, which consists of epithelial tissue covering the uterus’ exterior portion. The middle layer, or myometrium, is a thick layer of smooth muscle responsible for uterine contractions. Most of the uterus is myometrial tissue, and the muscle fibers run horizontally, vertically, and diagonally, allowing the powerful contractions that occur during labor and the less powerful contractions (or cramps) that help to expel menstrual blood during menstruation. Anteriorly directed myometrial contractions also occur near the time of ovulation and are thought to possibly facilitate the transport of sperm through the female reproductive tract.

The innermost layer of the uterus is called the endometrium. The endometrium contains a connective tissue lining, the lamina propria, which is covered by the epithelial tissue that lines the lumen. The endometrium consists of two layers: the stratum basalis (the basal layer) and the stratum functionalis (the functional layer).

The stratum basalis layer is the part of the lamina propria adjacent to the myometrium; this layer does not shed during menses. The stratum functionalis layer is thicker and contains the glandular portion of the lamina propria and the endothelial tissue that lines the uterine lumen. This layer grows and thickens in response to increased levels of estrogen and progesterone. In the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle, branches off of the uterine artery called spiral arteries supply this thickened stratum functionalis. This inner functional layer provides the proper site of implantation for the fertilized egg. If fertilization did not occur, the stratum functionalis layer of the endometrium sheds during menstruation.

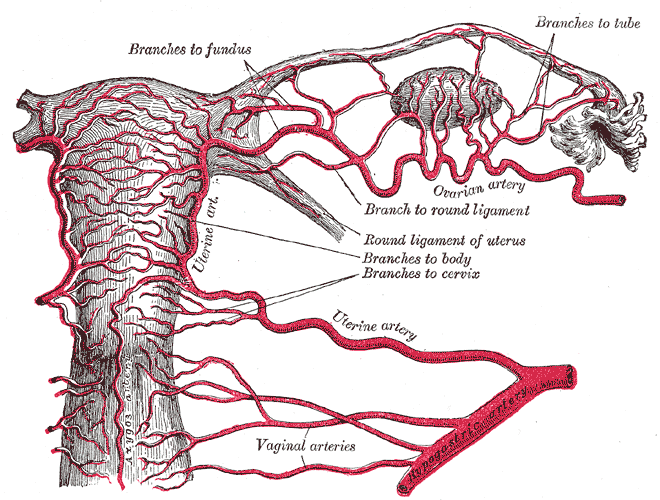

Uterine Vessels

The uterus gets its blood supply through the uterine artery, a branch of the internal iliac artery which runs through the cardinal ligament. The uterine artery supplies the myometrium and gives straight arteries branches that run close to the base of the endometrium to supply the stratum basale. The arteries become spiral and more helical arteries run along the whole length of the functionalis layer of the endometrium. Spiral arteries elongate and become tortuous with the effect of hormones and rupture and shed blood with each menstrual cycle (Figure 6).

Uterine Cervix

The uterine cervix opens to the vagina through external os and the junction between the uterine cervix, the and uterine body is marked by internal os. The pathway between the internal and external ostia is called the cervical canal or endocervix. The cervical wall is thinner than the wall of the body of the uterus, with few smooth muscle layers. The portion of the uterine cervix extending into the vagina is called the ectocervix.

The cervical canal is lined by columnar epithelial mucosal glands that secrete thick, mucous, acidic secretions. These secretions fill and seal the cervical canal and form a mucous plug, which prevents the penetration of pathogens to the uterus. At the midpoint of the menstrual cycle, under the influence of high systemic plasma estrogen concentrations, these secretions became thin and watery in nature, and help to facilitate entry of sperms through the reproductive tract.

The ectocervix is lined by stratified squamous epithelia cells. During a pap smear (Figure 7), cells from your cervix are gently scraped away and examined to detect potentially precancerous and cancerous processes. Abnormal growth changes in the type of epithelia is a concern, and intervention is aimed at preventing the progression of disease.

Take Home Message

- The uterus is anteverted and its wall consists of the perimetrium, myometrium, and endometrium.

- The endometrium consists of the stratum basalis and functionalis layers.

- The uterine cervix is thinner than the body of the uterus as it has fewer smooth muscles. It is lined by mucosal glands that secrete acidic and mucous secretions, and a mucous plug.

- Changes in cervical lining mucosa taken during pap smears can detect precancerous conditions.

Image Sources

- Figure 1. “Ovaries, Uterine Tubes, and Uterus ” is from OpenStax Anatomy & Physiology, licensed CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction (Micrographs provided by the Regents of University of Michigan Medical School © 2012).

- Figure 2. “Pelvis floor” is from Bruce Blaus via Wikimedia Commons, licensed CC BY SA 4.0.

- Figure 3. “Uterus and its supportive ligaments” is from Zealthy via Wikimedia Commons, licensed CC BY SA 4.0.

- Figure 4. “Uterine prolapse” is from Bruce Blaus via Wikimedia Commons, licensed CC BY SA 4.0.

- Figure 5. “Culdocentesis” is from Health Education to Villages, as allowed by their reproduction policy.

- Figure 6A. “Blood supply of the female reproduction system” is from Gray’s Anatomy. Public domain.

- Figure 6B. “Uterine arterial vasculature” is from Mikael Häggström via Wikimedia Commons. Public domain.

- Figure 7. “Pap smear” is © The Cleveland Clinic. Used for educational purpose under fair use.