Physical Development in Late Adulthood

Diana Lang; Nick Cone; Sonja Ann Miller; Daniel Dickman; Urtano Annele; K. Jyvakorpi Satu; and E. Strandberg Timo

In this section, you’ll learn more about physical changes in late adulthood. We are continually learning more about how to promote greater health during the aging process.[1]

Watch this clip from Marco Pahor, a professor in the University of Florida department of aging and geriatric research, as he discusses his research about ways physical activity affects the mobility of older adults and how it may result in longer life, lower medical costs, and increased long-term independence.

Defining Late Adulthood: Age or Quality of Life?

We are considered in late adulthood from the time we reach our mid-sixties until death. Because we are living longer, late adulthood is getting longer. Whether we start counting at 65, as demographers may suggest, or later, there is a greater proportion of people alive in late adulthood than anytime in world history. A 10-year-old child today has a 50 percent chance of living to age 104. Some demographers have even speculated that the first person ever to live to be 150 is alive today.

About 15.2 percent of the U.S. population or 49.2 million Americans are 65 and older.[2] This number is expected to grow to 98.2 million by the year 2060, at which time people in this age group will comprise nearly one in four U.S. residents. Of this number, 19.7 million will be age 85 or older. Developmental changes vary considerably among this population, so it is further divided into categories of 65 plus, 85 plus, and centenarians for comparison by the census.[3]

Demographers use chronological age categories to classify individuals in late adulthood. Developmentalists, however, divide this population in to categories based on physical and psychosocial well-being, in order to describe one’s functional age. The “young old” are healthy and active. The “old old” experience some health problems and difficulty with daily living activities. The “oldest old” are frail and often in need of care. A 98 year old woman who still lives independently, has no major illnesses, and is able to take a daily walk would be considered as having a functional age of “young old”. Therefore, optimal aging refers to those who enjoy better health and social well-being than average (Figure 2).

Normal aging refers to those who seem to have the same health and social concerns as most of those in the population. However, there is still much being done to understand exactly what normal aging means. Impaired aging refers to those who experience poor health and dependence to a greater extent than would be considered normal. Aging successfully involves making adjustments as needed in order to continue living as independently and actively as possible. This is referred to as selective optimization with compensation. Selective Optimization With Compensation is a strategy for improving health and well being in older adults and a model for successful aging. It is recommended that seniors select and optimize their best abilities and most intact functions while compensating for declines and losses. This means, for example, that a person who can no longer drive, is able to find alternative transportation, or a person who is compensating for having less energy, learns how to reorganize the daily routine to avoid overexertion. Perhaps nurses and other allied health professionals working with this population will begin to focus more on helping patients remain independent by optimizing their best functions and abilities rather than on simply treating illnesses. Promoting health and independence are essential for successful aging.

Systematic examination of old age is a new field inspired by the unprecedented number of people living long enough to become elderly. Developmental psychologists Paul and Margret Baltes have proposed a model of adaptive competence for the entire life span, but the emphasis here is on old age. Their model SOC (Selection, Optimization, and Compensation) is illustrated with engaging vignettes of people leading fulfilling lives, including writers Betty Friedan and Joan Erikson, and dancer Bud Mercer. Segments of the cognitive tests used by the Baltes in assessing the mental abilities of older people are shown. Although the video clip show below is old and dated, it remains an intellectually appealing video in which the Baltes discuss personality components that generally lead to positive aging experiences.

Try It

Age Categories

Senescence, or biological aging, is the gradual deterioration of functional characteristics (Figure 3).[4]

The Young Old—65 to 74

These 18.3 million Americans tend to report greater health and social well-being than older adults. Having good or excellent health is reported by 41 percent of this age group.[5] Their lives are more similar to those of midlife adults than those who are 85 and older. This group is less likely to require long-term care, to be dependent or to be poor, and more likely to be married, working for pleasure rather than income, and living independently. About 65 percent of men and 50 percent of women between the ages of 65-69 continue to work full-time.[6]

Physical activity tends to decrease with age, despite the dramatic health benefits enjoyed by those who exercise. People with more education and income are more likely to continue being physically active. And males are more likely to engage in physical activity than are females. The majority of the young-old continue to live independently. Only about 3 percent of those 65-74 need help with daily living skills as compared with about 22.9 percent of people over 85. Another way to consider this is that 97 percent of people between 65-74 and 77 percent of people over 85 do not require assistance! This age group is less likely to experience heart disease, cancer, or stroke than the old, but nearly as likely to experience depression.[7]

The Old Old—75 to 84

This age group is more likely to experience limitations on physical activity due to chronic disease such as arthritis, heart conditions, hypertension (especially for women), and hearing or visual impairments. Rates of death due to heart disease, cancer, and cerebral vascular disease are double that experienced by people 65-74. Poverty rates are 3 percent higher (12 percent) than for those between 65 and 74. However, the majority of these 12.9 million Americans live independently or with relatives. Widowhood is more common in this group-especially among women.

The Oldest Old—85 plus

The number of people 85 and older is 34 times greater than in 1900 and now includes 5.7 million Americans. This group is more likely to require long-term care and to be in nursing homes. However, of the 38.9 million American over 65, only 1.6 million require nursing home care. Sixty-eight percent live with relatives and 27 percent live alone.[8][9]

The Centenarians

Centenarians, or people aged 100 or older, are both rare and distinct from the rest of the older population (Figure 4). Although uncommon, the number of people living past age 100 is on the rise; between the year 2000 and 2014, then number of centenarians increased by over 43.6%, from 50,281 in 2000 to 72,197 in 2014.[10] In 2010, over half (62.5 percent) of the 53,364 centenarians were age 100 or 101.[11]

This number is expected to increase to 601,000 by the year 2050.[12] The majority is between ages 100 and 104 and eighty percent are women. Out of almost 7 billion people on the planet, about 25 are over 110. Most live in Japan, a few live the in United States and three live in France (National Institutes of Health, 2006). These “super-Centenarians” have led varied lives and probably do not give us any single answers about living longer. Jeanne Clement smoked until she was 117. She lived to be 122. She also ate a diet rich in olive oil and rode a bicycle until she was 100. Her family had a history of longevity. Pitskhelauri[13] suggests that moderate diet, continued work and activity, inclusion in family and community life, and exercise and relaxation are important ingredients for long life.

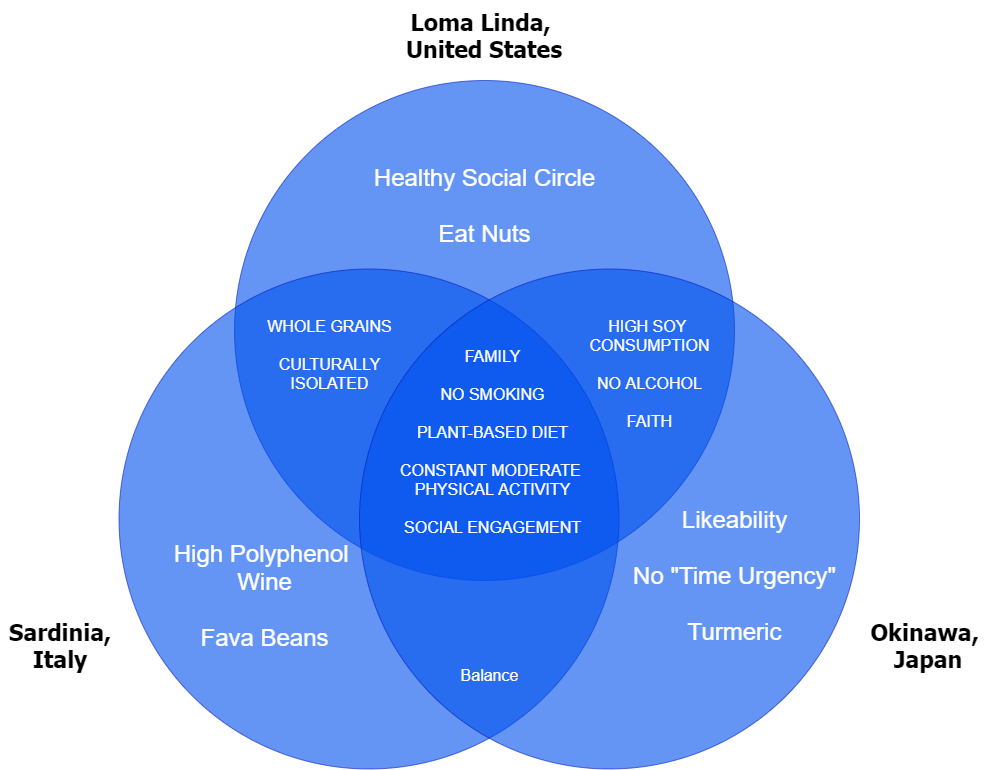

Recent research on longevity reveals that people in some regions of the world live significantly longer than people elsewhere. Efforts to study the common factors between these areas and the people who live there is known as blue zone research (Figure 5). Blue zones are regions of the world where Dan Buettner claims people live much longer than average. The term first appeared in his November 2005 National Geographic magazine cover story, “The Secrets of a Long Life.” Buettner identified five regions as “Blue Zones”: Okinawa (Japan); Sardinia (Italy); Nicoya (Costa Rica); Icaria (Greece); and the Seventh-day Adventists in Loma Linda, California. He offers an explanation, based on data and first hand observations, for why these populations live healthier and longer lives than others.

The people inhabiting blue zones share common lifestyle characteristics that contribute to their longevity. The Venn diagram below highlights the following six shared characteristics among the people of Okinawa, Sardinia, and Loma Linda blue zones. Though not a lifestyle choice, they also live as isolated populations with a related gene pool.

- Family, put ahead of other concerns

- Less smoking

- Semi-vegetarianism, when the majority of food consumed is derived from plants

- Constant moderate physical activity as an inseparable part of life

- Social engagement, when people of all ages are socially active and integrated into their communities

- Legumes are commonly consumed

In his book, Buettner provides a list of nine lessons, covering the lifestyle of blue zones people:

- Moderate, regular physical activity

- Life purpose

- Stress reduction

- Moderate caloric intake

- Plant-based diet

- Moderate alcohol intake, especially wine

- Engagement in spirituality or religion

- Engagement in family life

- Engagement in social life

Try It

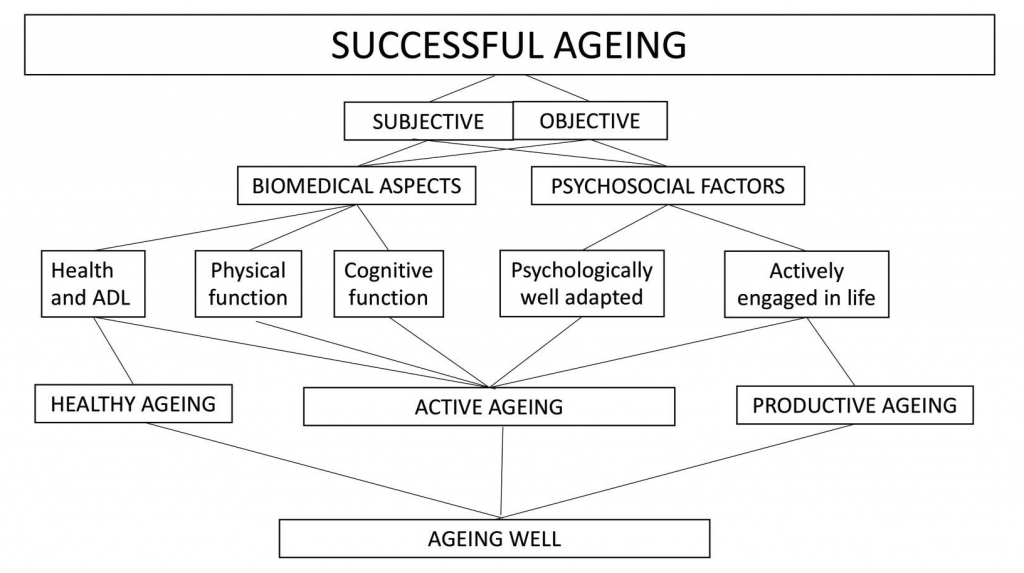

Successful Aging

“Successful aging” is a concept that describes the quality of aging. Studies continually use a variety of definitions for “successful aging.” For this book, “successful aging” is defined as encompassing the physical, functional, social, and psychological health domains of an individual.[14][15][16][17] Because a variety of terms and dimensions of successful aging are used, we have included Figure 6 as a brief overview.

Most definitions of “successful aging” also include objective measurements of outcomes based on an individual’s overall health and functionality.[18]

Although definitions of successful aging are value-laden, Rowe and Kahn[19] defined three criteria of successful aging that are useful for research and behavioral interventions. They include:

- Relative avoidance of disease, disability, and risk factors, like high blood pressure, smoking, or obesity

- Maintenance of high physical and cognitive functioning

- Active engagement in social and productive activities

For example, research has demonstrated that age-related declines in cognitive functioning across the adult life span may be slowed through physical exercise and lifestyle interventions.[20]

Another way that older adults can respond to the challenges of aging is through compensation. Specifically, selective optimization with compensation is used when the elder makes adjustments, as needed, in order to continue living as independently and actively as possible.[21] When older adults lose functioning, referred to as loss-based selection, they may first use new resources/technologies or continually practice tasks to maintain their skills. However, when tasks become too difficult, they may compensate by choosing other ways to achieve their goals. For example, a person who can no longer drive needs to find alternative transportation, or a person who is compensating for having less energy, learns how to reorganize the daily routine to avoid over-exertion.

- This chapter was adapted from select chapters in Waymaker Lifespan Development, authored by Sonja Ann Miller and Daniel Dickman for Lumen Learning and available under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike license. The section on Successful Aging is adapted from "Definitions of successful ageing: A brief review of a multidimensional concept" by Urtano Annele, K. Jyvakorpi Satu, and E. Strandberg Timo, available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Some selections from Lumen Learning were adapted from previously shared content from Laura Overstreet's Lifespan Psychology, Wikipedia, and The Noba Project. ↵

- US Census Bureau. (2018, April 10). The Nation's Older Population Is Still Growing, Census Bureau Reports. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2017/cb17-100.html ↵

- US Census Bureau. (2018, August 03). Newsroom. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/facts-for-features/2017/cb17-ff08.html ↵

- Senescence. (n.d.). https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/senescence ↵

- Chapman, D. P., Williams, S. M., Strine, T. W., Anda, R. F., & Moore, M. J. (2006, February 18). Preventing Chronic Disease: April 2006: 05_0167. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2006/apr/05_0167.htm ↵

- He, W., Sengupta, M., Velkoff, V., & DeBarros, K. (n.d.). U. S. Census Bureau, Current Popluation Reports, P23‐209, 65+ in the United States: 2005 (United States, U. S. Census Bureau). www.census.gov/prod/1/pop/p23‐190/p23‐190.html ↵

- He, W., Sengupta, M., Velkoff, V., & DeBarros, K. (n.d.). U. S. Census Bureau, Current Popluation Reports, P23‐209, 65+ in the United States: 2005 (United States, U. S. Census Bureau). www.census.gov/prod/1/pop/p23‐190/p23‐190.html ↵

- He, W., Sengupta, M., Velkoff, V., & DeBarros, K. (n.d.). U. S. Census Bureau, Current Popluation Reports, P23‐209, 65+ in the United States: 2005 (United States, U. S. Census Bureau). www.census.gov/prod/1/pop/p23‐190/p23‐190.html ↵

- Newsroom: Facts for Features & Special Editions: Facts for Features: Older Americans Month: May 2010. (2011, February 22). Census Bureau Home Page. http://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/facts_for_features_special_editions/cb10-ff06.html ↵

- Jiaquan, X. (2016). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Mortality Among Centenarians in the United States, 2000─2014. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db233.pdf. ↵

- US Census Bureau. (2018, August 03). Newsroom. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/facts-for-features/2017/cb17-ff08.html ↵

- Newsroom: Facts for Features & Special Editions: Facts for Features: Older Americans Month: May 2010. (2011, February 22). Census Bureau Home Page. http://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/facts_for_features_special_editions/cb10-ff06.html ↵

- Berger, K. S. (2005). The developing person through the life span (6th ed.). New York: Worth. ↵

- Cosco, T. D., Prina, A. M., Perales, J., Stephan, B. C. M., & Brayne, C. (2014). Operational definitions of successful aging: a systematic review. International Psychogeriatrics, 26(3), 373–381. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610213002287 ↵

- Fries, J. F. (1980). Aging, natural death, and the compression of morbidity. The New England Journal of Medicine, 303(3), 130–135. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM198007173030304 ↵

- Martin, P., Kelly, N., Kahana, B., Kahana, E., Willcox, B. J., Willcox, D. C., & Poon, L. W. (2015). Defining successful aging: a tangible or elusive concept? The Gerontologist, 55(1), 14–25. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnu044 ↵

- Depp, C. A., & Jeste, D. V. (2006). Definitions and predictors of successful aging: A comprehensive review of larger quantitative studies. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry: Official Journal of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, 14(1), 6–20. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.jgp.0000192501.03069.bc ↵

- Fernández-Ballesteros, R. (2019). The concept of successful aging and related terms. In The Cambridge Handbook of Successful Aging (pp. 6–22). Cambridge University Press. ↵

- Rowe, J. W., & Kahn, R. L. (1997). Successful aging. The Gerontologist, 37(4), 433–440. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/37.4.433 ↵

- Rowe, J. W., & Kahn, R. L. (1997). Successful aging. The Gerontologist, 37(4), 433–440. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/37.4.433 ↵

- Baltes, B. B., & Dickson, M. W. (2001). Using life-span models in industrial-organizational psychology: The theory of selective optimization with compensation. Applied Developmental Science, 5(1), 51–62. https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532480xads0501_5 ↵