Physical Development in Middle to Late Childhood

Suzanne Valentine-French; Martha Lally; Stephanie Loalada; Laura Overstreet; Julie Lazzara; Alisa Beyer; Diana Lang; and Naomi H. Dan Karami

- Describe physical growth during middle childhood.

- Prepare recommendations to avoid health risks in school-aged children.

- Define and apply conservation, reversibility, and identity in concrete operational intelligence.

- Explain changes in processing during middle childhood according to information processing theory of memory.

- Characterize language development in middle childhood.

- Compare preconventional, conventional, and postconventional moral development.

- Define and describe communication disorders and learning disabilities.

- Evaluate the impact of labeling on children’s self-concept and social relationships.

- Apply the ecological systems model to explore children’s experiences in schools.

- Examine social relationships in middle childhood.

Middle and late childhood

Middle and late childhood spans the ages between early childhood and adolescence, approximately ages 6 to 11. Children gain greater control over the movement of their bodies, mastering many gross and fine motor skills that eluded the younger child. Changes in the brain during this age enable not only physical development, but contributes to greater reasoning and flexibility of thought. School becomes a big part of middle and late childhood, and it expands their world beyond the boundaries of their own family. Peers start to take center-stage, often prompting changes in the parent-child relationship. Peer acceptance also influences children’s perception of self and may have consequences for emotional development beyond these years.

Overall Physical Growth

Rates of growth generally slow during these years. Typically, a child will gain about 4-6 pounds a year and grow about 2-3 inches per year.[1] They also tend to slim down and gain muscle strength and lung capacity making it possible to engage in strenuous physical activity for long periods of time. The beginning of the growth spurt, which occurs prior to puberty, tends to begin two years earlier for females than males. In the U.S., the mean age for the beginning of growth spurts for females is nine, while for males it is eleven. Children of this age tend to sharpen their abilities to perform both gross motor skills, such as riding a bike, and fine motor skills, such as cutting their fingernails. In gross motor skills (involving large muscles) males typically outperform females, while females tend outperform males in fine motor skills (small muscles). These improvements in motor skills are related to brain growth and experience during this developmental period.

Brain Growth

Two major brain growth spurts occur during middle/late childhood.[2] Between ages 6 and 8, significant improvements in fine motor skills and eye-hand coordination are noted. Then between 10 and 12 years of age, the frontal lobes become more developed and improvements in logic, planning, and memory are evident.[3] Myelination is one factor responsible for these growths. From age 6 to 12, the nerve cells in the association areas of the brain, that is those areas where sensory, motor, and intellectual functioning connect, become almost completely myelinated.[4] This myelination contributes to increases in information processing speed and reaction time. The hippocampus, responsible for transferring information from the short-term to long-term memory, also show increases in myelination resulting in improvements in memory functioning.[5] Children in middle to late childhood are also better able to plan, coordinate activity using both left and right hemispheres of the brain, and control emotional outbursts. Paying attention is also typically improved as the prefrontal cortex matures.[6]

Sports

Middle childhood seems to be a great time to introduce children to organized sports, and in fact, many parents do. However, it has been suggested that the emphasis on competition and athletic skill can be counterproductive and lead children to grow tired of the game and want to quit. In many respects, children’s activities are no longer children’s activities once some adults become overly involved and approach games as adults rather than children.

Sports are important for children. Children’s participation in sports has been linked to:

- Higher levels of satisfaction with family and overall quality of life in children,

- Improved physical and emotional development, and

- Better academic performance.

Studies have identified barriers to engaging in sports among children. Some of the barriers included enormous amounts of interaction with technology, cost, including traveling expenses, equity (limited access to minority children and children with special needs), and concerns about injuries from parents and untrained coaches.[7]

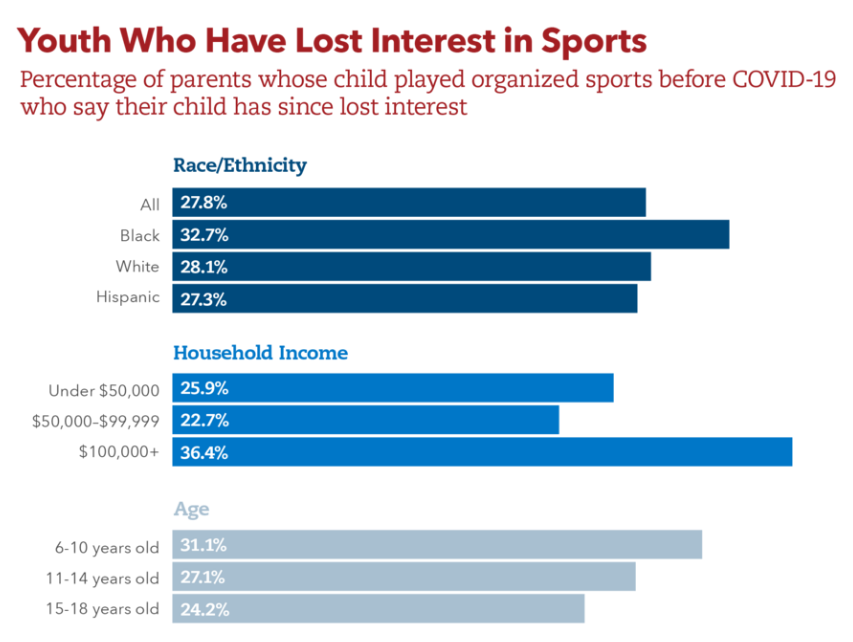

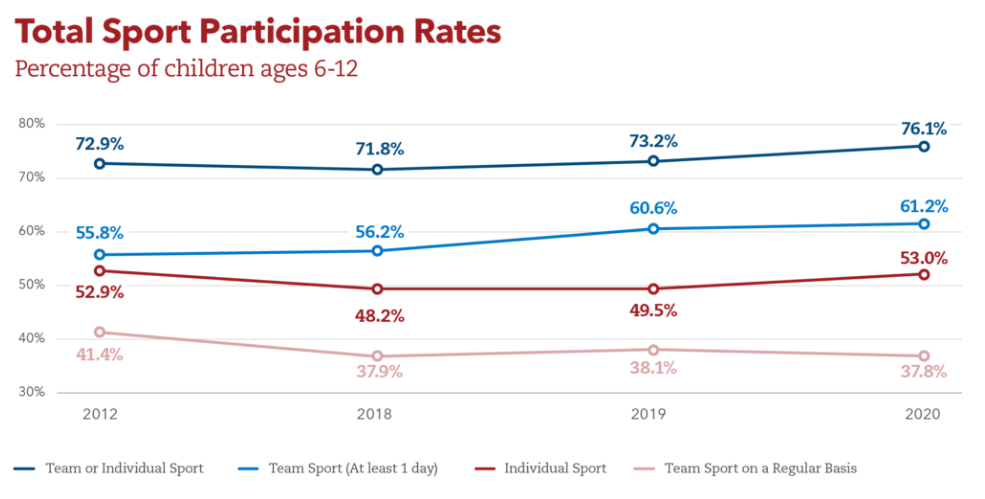

Many youth lost interest in sports even before the COVID pandemic. Figure 1 denotes disparities among children who have lost interest in sports. We also notice in Figure 2 that there is a decrease in the total sports participation rates in regards to team sports on a regular basis.[8]

Welcome to the world of e-sports

The recent Sport Policy and Research Collaborative (SPARC)[9] report on the “State of Play” in the United States highlights a disturbing trend. One in four children between the ages of 5 and 16 rate playing computer games with their friends as a form of exercise. In addition, e-sports, which as SPARC writes is about as much a sport as poker, involves children watching other children play video games.

Since 2008 there has also been a downward trend in the number of sports children are engaged in, despite a body of research evidence that suggests specializing in only one activity can increase the chances of injury, while playing multiple sports can be more protective.[10] A University of Wisconsin study found that 49% of athletes who specialized in a sport experienced an injury compared with 23% of those who played multiple sports.[11]

Physical Education: For many children, physical education in school is a key component in introducing children to sports. After years of schools cutting back on physical education programs, there has been a turn around, prompted by concerns over childhood obesity and related health issues.

Health Risks: Childhood Obesity

In the U.S., nearly 20 percent of children and adolescents were considered obese in 2017-2018.[12] This is defined as being at least 20 percent over their ideal weight.[13] The percentage of obesity in school-aged children has increased substantially since the 1960s, and it continues to increase. This is true in part because of the introduction of a steady diet of television and other sedentary activities. In the U.S., many have come to emphasize high fat, fast foods as a culture. Pizza, hamburgers, chicken nuggets, and prepackaged meals with soda have replaced more nutritious foods as staples.

One consequence of childhood obesity is that children run the risk of suffering orthopedic problems such as knee injuries and an increased risk of heart disease and stroke in adulthood. In addition, the number of cases of pediatric diabetes has risen dramatically in recent years.

Dieting is not really the solution to childhood obesity. If you diet, your basal metabolic rate tends to decrease thereby making the body burn even fewer calories in order to maintain the weight. Increased activity is much more effective in lowering weight and improving children’s health and psychological well-being. Exercise reduces stress; therefore, caregivers should take caution against emphasizing diet alone to avoid the development of any dieting obsession that can lead to disordered eating patterns. Again, increasing a child’s activity level is most helpful.

Behavioral interventions, including training children to overcome impulsive behavior, are being researched to help curtail childhood obesity.[14] Practicing inhibition has been shown to strengthen the ability to resist unhealthy foods. Caregivers can help children the best when they are warm and supportive without using shame or guilt. Caregivers can also act like the child’s frontal lobe until it is developed by helping them make correct food choices and praising their efforts.[15]

Sexual Development

Once children enter grade school (approximately ages 7–12), their awareness of social rules increases and they may become more modest and want more privacy, particularly around adults. Curiosity about adult sexual behavior also tends to increases—particularly as puberty approaches—and children may begin to seek out sexual content in television, movies, the internet, and printed material. Children approaching puberty may also start displaying romantic and sexual interest in their peers.

- Johns Hopkins Medicine (2022). The growing child: 3-year-olds. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/wellness-and-prevention/the-growing-child-3yearolds ↵

- Spreen, O., Rissser, A., & Edgell, D. (1995). Developmental neuropsychology. New York: Oxford University Press. ↵

- van der Molen, M., & Molenaar, P. (1994). Cognitive psychophysiology: A window to cognitive development and brain maturation. In G. Dawson & K. Fischer (Eds.), Human behavior and the developing brain. New York: Guilford. ↵

- Johnson, M. (2005). Developmental neuroscience, psychophysiology, and genetics. In M. Bornstein & M. Lamb (Eds.), Developmental science: An advanced textbook (5th ed., pp. 187-222). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum ↵

- Rolls, E. T. (2000). Memory systems in the brain. Annual Review of Psychology, 51(1), 599–630. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.51.1.599 ↵

- Markant, J. C., & Thomas, K. M. (2013). Postnatal brain development. In P. D. Zelazo (Ed.), Oxford handbook of developmental psychology. New York: Oxford University Press. ↵

- Sports and Fitness Industry Association (SFIA). (2018, June 15). Soccer participation in the United States. Medium. https://sfia.medium.com/soccer-participation-in-the-united-states-92f8393f6469 ↵

- The Aspen Institute Project Play. (n.d.). Youth Sports Facts: Participation rates. https://www.aspenprojectplay.org/youth-sports/facts/participation-rates ↵

- Sport Policy and Research Collaborative (2016). State of play 2016: Trends and developments. The Aspen Institute. https://www.aspeninstitute.org/publications/state-play-2016-trends-developments/ ↵

- Sport Policy and Research Collaborative (2016). State of play 2016: Trends and developments. The Aspen Institute. https://www.aspeninstitute.org/publications/state-play-2016-trends-developments/ ↵

- McGuine, T. A. (2016). The association of sport specialization and the history of lower extremity injury in high school athletes. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 48, 866. https://doi.org/10.1249/01.mss.0000487597.82416.4d ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021, April 5). Childhood obesity facts. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/childhood.html ↵

- Harvard School of Public Health. (n.d.) Child Obesity. https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/obesity-prevention-source/obesity-trends/global-obesity-trends-in-children/. ↵

- Lu, S. (2016). Obesity and the growing brain. Monitor on Psychology, 47(6), 40-43. ↵

- Liang, J., Matheson, B. E., Kaye, W. H., & Boutelle, K. N. (2014). Neurocognitive correlates of obesity and obesity-related behaviors in children and adolescents. International Journal of Obesity (2005) , 38(4), 494–506. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2013.142 ↵