Physical Development in Adolescence

Diana Lang; Nick Cone; Tera Jones; Lumen Learning; OpenStax College; Martha Lally; and Suzanne Valentine-French

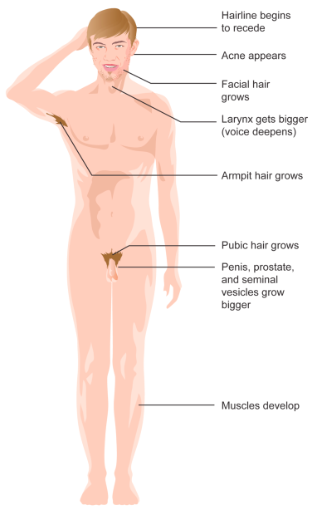

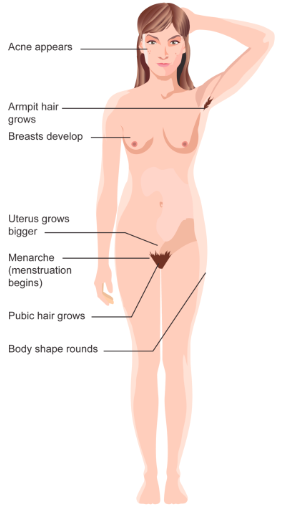

Physical changes of puberty mark the onset of adolescence.[1] These changes include a growth spurt in height, growth of pubic and underarm hair, and skin changes (e.g., pimples). Males experience growth in facial hair and a deepening of their voice. Females experience breast development and begin menstruating. These pubertal changes are driven by hormones, particularly an increase in testosterone for males and estrogen for females.

In the United States, puberty typically begins, on average, at age 10–11 years for females and 11–12 years for males. Pubertal changes take around three to four years to complete. While the sequence of physical changes in puberty is predictable, the onset and pace of puberty vary widely. Every person’s individual timetable for puberty is different and is primarily influenced by heredity; however, environmental factors—such as diet and exercise—also exert some influence.

Physical Growth Spurt

Adolescents experience an overall physical growth spurt. The growth proceeds from the extremities toward the torso. This is referred to as distal proximal development. First the hands grow, then the arms, and finally the torso. The overall physical growth spurt results in 10-11 inches of added height and 50 to 75 pounds of increased weight. The head begins to grow sometime after the feet have gone through their period of growth. Growth of the head is preceded by growth of the ears, nose, and lips. The difference in these patterns of growth result in adolescents appearing awkward and out-of-proportion. As the torso grows, so does the internal organs. The heart and lungs experience dramatic growth during this period.

During this stage, children are quite similar in height and weight. However, gender differences become apparent during adolescence. From approximately age 10 to 14, the average female is taller but not heavier than the average male. For females the growth spurt begins between 8 and 13 years old (average 10-11), with adult height reached between 10 and 16 years old. After that, the average male becomes both taller and heavier, although individual differences are certainly noted. Males tend to begin their growth spurt slightly later, usually between 10 and 16 years old (average 12-13), and typically reach their adult height between 13 and 17 years old. As adolescents physically mature, weight differences are more noteworthy than height differences. At eighteen years of age, those that are heaviest weigh almost twice as much as the lightest, but the tallest teens are only about 10% taller than the shortest.[2] Both nature (i.e., genes) and nurture (e.g., nutrition, medications, and medical conditions) can influence both height and weight.

Both height and weight can certainly be sensitive issues for some teenagers. Yet, neither socially preferred height nor thinness is the destiny for many individuals. Being overweight, in particular, has become a common, serious problem in modern society due to the prevalence of diets high in fat and lifestyles low in activity.[3]

Average height and weight are also related somewhat to racial and ethnic background. In general, children of Asian background tend to be slightly shorter than children of European and North American background. The latter in turn tend to be shorter than children from African societies.[4] Body shape differs slightly as well, though the differences are not always visible until after puberty. Asian background youth tend to have arms and legs that are a bit short relative to their torsos, and African background youth tend to have relatively long arms and legs. The differences are only averages as there are large individual differences as well.

Puberty is a period of rapid growth and sexual maturation. These changes begin sometime between 8 and 14. Puberty occurs over two distinct phases, and the first phase, adrenarche, begins at 6 to 8 years of age and involves increased production of adrenal androgens that contribute to a number of pubertal changes—such as skeletal growth.

Hormonal Changes

The second phase of puberty, gonadarche, begins several years later and involves increased production of hormones governing physical and sexual maturation. Puberty involves distinctive physiological changes in an individual’s height, weight, body composition, and circulatory and respiratory systems, and during this time, both the adrenal glands and sex glands mature. These changes are largely influenced by hormonal activity. Many hormones contribute to the beginning of puberty, but most notably a major rush of estrogen for females and testosterone for males. Hormones play an organizational role (priming the body to behave in a certain way once puberty begins) and an activational role (triggering certain behavioral and physical changes). During puberty, the adolescent’s hormonal balance shifts strongly towards an adult state; the process is triggered by the pituitary gland, which secretes a surge of hormonal agents into the blood stream and initiates a chain reaction.

Sexual Development

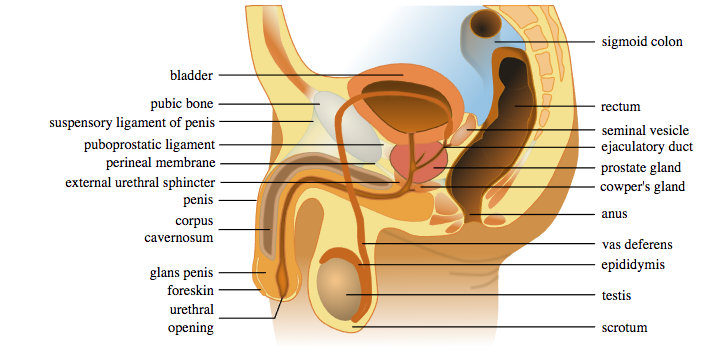

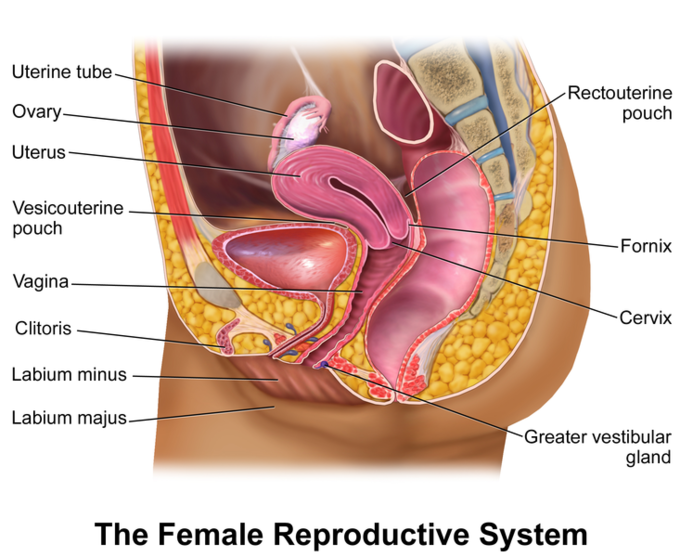

Typically, the growth spurt is followed by the development of sexual maturity. Sexual changes are divided into two categories: Primary sexual characteristics and secondary sexual characteristics. Primary sexual characteristics are changes in the reproductive organs. For males, this includes growth of the testes, penis, scrotum, and spermarche or first ejaculation of semen. This occurs between 11 and 15 years of age. Males produce their sperm on a cycle, and unlike the female’s ovulation cycle, the male sperm production cycle is constantly producing millions of sperm daily. The main sex organs for those assigned male at birth are the penis and the testicles, the latter of which produce semen and sperm (see Figure 1). For those assigned female at birth, primary characteristics include growth of the uterus and menarche or the first menstrual period. The female gametes, which are stored in the ovaries, are present at birth but are immature (see Figure 2). Each ovary contains about 400,000 gametes, but only 500 will become mature eggs.[5] Beginning at puberty, one ovum ripens and is released about every 28 days during the menstrual cycle. Stress and a higher percentage of body fat can bring menstruation at younger ages.

Secondary sexual characteristics are visible physical changes not directly linked to reproduction, but signal sexual maturity. For those assigned male at birth, this includes broader shoulders and a lower voice as the larynx grows. Hair becomes coarser and darker, and hair growth occurs in the pubic area, under the arms, and on the face (see Figure 3). For those assigned female at birth, breast development occurs around age 10, although full development takes several years. Hips broaden and pubic and underarm hair develops and also becomes darker and coarser (See Figure 4).

Acne: An unpleasant consequence of the hormonal changes in puberty is acne, defined as pimples on the skin due to overactive sebaceous (oil-producing) glands.[6] These glands develop at a greater speed than the skin ducts that discharges the oil. Consequently, the ducts can become blocked with dead skin and acne will develop. Experiencing acne can lead the adolescent to withdraw socially, especially if they are self-conscious about their skin or teased.[7]

Effects of Pubertal Age

The age of puberty is getting younger for children throughout most of the world. According to Euling et al.,[8] data are sufficient to suggest a trend toward an earlier breast development onset and menarche in those with female internal sex organs. A century ago the average age of someone with female internal sex organs to experience their first period (in the United States and Europe) was 16, while today it is around 13. Because there is no clear marker of puberty for those with male internal sex organs, it is harder to determine if males assigned at birth are maturing earlier too. In addition to better nutrition, less positive reasons associated with early puberty for those with internal female sex organs include increased stress, obesity, and endocrine disrupting chemicals.

Cultural differences are noted with Asian-American females, on average, developing last, while African American females tend to enter puberty the earliest. Hispanic females start puberty the second earliest, while European-American females tend to rank third in their age of starting puberty. Although African American females are typically the first to develop, they are less likely to experience negative consequences of early puberty when compared to European-American females.[9] Research has demonstrated mental health problems can be linked to children who begin puberty earlier than their peers. For females, early puberty is associated with depression, substance use, eating disorders, disruptive behavior disorders, and early sexual behavior.[10] Some early maturing females demonstrate more anxiety and less confidence in their relationships with family and friends and they compare themselves more negatively to their peers.[11]

Additionally, mental health problems are more likely to occur when a child is among the first in their peer group to develop. Because the preadolescent time is one of not wanting to appear different, early developing children stand out among their peer group and gravitate toward those who are older. For females, this results in them interacting with older peers who engage in risky behaviors such as substance use and early sexual behavior.[12] Males also see changes in their emotional functioning at puberty. According to Mendle, Harden, Brooks-Gunn, and Graber,[13] while most males experienced a decrease in depressive symptoms during puberty, males who began puberty earlier and exhibited a rapid tempo, or a fast rate of change, actually increased in depressive symptoms. The researchers concluded that the transition in peer relationships might be especially challenging for males whose pattern of pubertal maturation differs significantly from those of others their age. Consequences for males attaining early puberty was increased odds of cigarette, alcohol, or other drug use.[14]

Brain and Cognitive Changes

The human brain is not fully developed by the time a person reaches puberty. Between the ages of 10 and 25, the brain undergoes significant changes that have important implications for behavior. The brain reaches 90% of its adult size by the time a person is six or seven years of age. Thus, the brain does not grow in size much during adolescence. However, the creases in the brain continue to become more complex until the late teens. The biggest changes in the folds of the brain during this time occur in the parts of the cortex that process cognitive and emotional information. During adolescence, myelination and synaptic pruning in the prefrontal cortex increase, improving the efficiency of information processing, and neural connections between the prefrontal cortex and other regions of the brain are strengthened. However, this growth takes time and the growth is uneven. Additionally, changes in both the levels of the neurotransmitters dopamine and serotonin in the limbic system tend to make adolescents more emotional and more responsive to rewards and stress. In the next section, we will learn about changes in the brain and why teenagers sometimes engage in increased risk-taking behaviors and have varied emotions.

The Adolescent Brain: 7 Key Points to Understand

As you learn about brain development during adolescence, consider these key points[15]:

- The brain reaches its biggest size in early adolescence (see Figure 5).

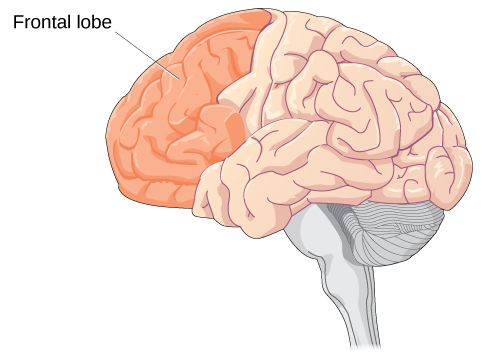

- The brain continues to mature even after it is done growing; it does not finish developing and maturing until the mid- to late 20s (see Figure 5). The front part of the brain, called the prefrontal cortex, is one of the last brain regions to mature. This area is responsible for skills like planning, prioritizing, and controlling impulses. Because these skills are still developing, teens are more likely to engage in risky behaviors without considering the potential results of their decisions.

- The teen brain is very plastic and ready to learn and adapt.

- Many mental disorders may begin to appear during adolescence due to the vast changes (e.g., brain, physical, emotional, and social) that tend to occur during this stage. Mental disorders such schizophrenia, anxiety, depression, bipolar disorder, and eating disorders tend to be diagnosed during this developmental period.

- Teen brains may be more vulnerable to stress because many teens respond to stress differently than adults, thus leading to stress-related mental health issues such as anxiety and depression. Mindfulness, which is a psychological process of actively paying attention to the present moment, may help teens cope with and reduce stress. More information on managing stress is available in the National Institute of Mental Health’s fact sheet, I’m So Stressed Out.[16]

- Teens need more sleep than children and adults. Research shows that melatonin (the “sleep hormone”) levels in the blood are naturally higher later at night and drop later in the morning in teens than in most children and adults. This difference may explain why many teens stay up late and struggle with getting up in the morning. Teens should get about 9 to 10 hours of sleep a night, but most teens do not get enough sleep. A lack of sleep at any age can make it difficult to pay attention, may increase impulsivity, and may increase the risk for irritability or depression.

- The teen brain is resilient.

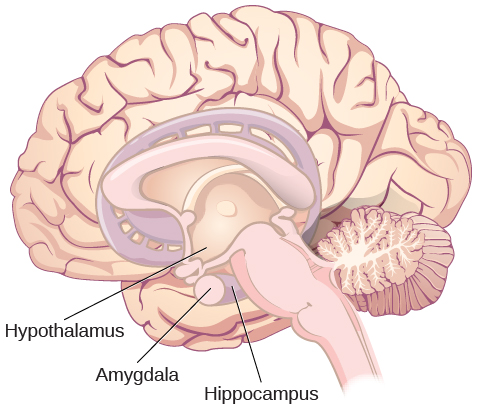

The limbic system is linked to the hormonal changes that occur during puberty and it develops years ahead of the front part of the brain, the prefrontal cortex (see Figure 6). Pubertal hormones target the amygdala (part of the limbic system) directly and powerful sensations become compelling.[17]Hormonal changes and the early development of the limbic system relates to novelty seeking, regulating emotions, determining rewards and punishments, and processing emotional experiences.

Changes in levels of neurotransmitters (dopamine and serotonin) in the limbic system can make adolescents more emotional and more responsive to rewards and stress compared to when they were younger. Dopamine is a neurotransmitter in the brain associated with pleasure and attuning to the environment during decision-making while serotonin, the “calming chemical,” eases tension and stress. During adolescence, dopamine levels in the limbic system (see Figure 7) increase and input of dopamine to the prefrontal cortex increases. This increased dopamine activity may have implications for adolescent risk-taking and vulnerability to boredom. Serotonin also puts a brake on the excitement and sometimes recklessness that dopamine can produce. If there is a defect in the serotonin processing in the brain, impulsive or violent behavior can result.

When the overall brain chemical system is working well, these chemicals tend to interact to balance out extreme behaviors. However, when stress, arousal, or sensations become extreme, the adolescent brain can be flooded with impulses that overwhelm the prefrontal cortex. As a result, adolescents may engage in increased risk-taking behaviors and emotional outbursts possibly because the frontal lobes of their brains are still developing. In addition to dopamine, the adolescent brain is affected by oxytocin, which facilitates bonding and makes social connections more rewarding.

The prefrontal cortex is one of the last brain regions to mature (see Figure 8). It is the area responsible for planning, prioritizing and controlling impulses and it is still maturing into early adulthood.[18] Brain scans confirm that cognitive control, revealed by fMRI studies, is not fully developed until adulthood because the prefrontal cortex is limited in connections and engagement.[19]

One of the world’s leading experts on adolescent development, Laurence Steinberg, likens this to engaging a powerful engine before the braking system is in place. The result is that many adolescents are more prone to risky behaviors than are children or adults.[20]

Many changes in the teen brain

In a digital world that is constantly changing, the adolescent brain is well prepared to adapt to new technology—and is shaped in return by experience. All the big changes the brain is experiencing may explain why adolescence is the time when many mental health issues—such as schizophrenia, anxiety, depression, bipolar disorder, and eating disorders—emerge. Although adolescence is a vulnerable time for the brain and for teenagers in general, most teens become healthy adults. Some changes in the brain during this important phase of development actually may help protect against long-term mental health issues.

Although the brain does not get larger during adolescence, it matures and becomes more interconnected and specialized.[21] The myelination and development of connections between neurons continue. This results in an increase in the white matter of the brain and allows adolescents to make significant improvements in their thinking and processing skills. Different brain areas become myelinated at different times. For example, the brain’s language areas undergo myelination during the first 13 years. With greater myelination, however, comes diminished plasticity as a myelin coating inhibits the growth of new connections.[22] Even as the connections between neurons are strengthened, synaptic pruning occurs more than during childhood as the brain adapts to changes in the environment. Further, the corpus callosum (see Figure 6.6), which connects the two hemispheres, continues to thicken allowing for stronger connections between brain areas. And, the hippocampus becomes more strongly connected to the frontal lobes, allowing for greater integration of memory and experiences into our decision making.

As mentioned in the introduction to adolescence, too many who have read the research on the teenage brain come to quick conclusions about adolescents as irrational loose cannons. However, adolescents are actually making choices influenced by a very different set of chemical influences than their adult counterparts—a hopped up reward system that can drown out warning signals about risk. Adolescent decisions are not always defined by impulsivity because of lack of brakes, but because of planned and enjoyable pressure to the accelerator. It is helpful to put all of these brain processes in developmental context.

To learn more, watch this video about adolescent brain research and more about how these changes in brain development also result in behavioral changes.

Additionally, the adolescent brain is especially vulnerable to damage from drug exposure. Consequently, adolescents are more sensitive to the effects of repeated marijuana exposure.[23] However, researchers have also focused on the highly adaptive qualities of the adolescent brain which allow the adolescent to move away from the family towards the outside world.[24][25] Novelty seeking and risk-taking can generate positive outcomes including meeting new people and seeking out new situations. Separating from the family and moving into new relationships and different experiences are actually quite adaptive for society.

Major changes in the structure and functioning of the brain occur during adolescence and result in cognitive and behavioral developments.[26] Cognitive changes during adolescence include a shift from concrete to more abstract and complex thinking. Such changes are fostered by improvements during early adolescence in attention, memory, processing speed, and metacognition (ability to think about thinking and therefore make better use of strategies like mnemonic devices that can improve thinking). As explained before, early in adolescence, changes in the brain’s limbic system contribute to increases in adolescents’ sensation-seeking and reward motivation. Later in adolescence, the brain’s cognitive control centers in the prefrontal cortex develop, increasing adolescents’ self-regulation and future orientation. In sum, the adolescent years are a time of intense brain changes, which typically result in enhanced cognitive functioning.

- Brown, B. B., & Larson, J. (2009). Peer relationships in adolescence. In R. M. Lerner & L. Steinberg (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent psychology (pp. 74–103). New York, NY: Wiley. ↵

- Seifert, K. (2012). Educational Psychology. http://cnx.org/content/col11302/1.2 ↵

- Tartamella, L., Herscher, E., Woolston, C. (2004). Generation extra large: Rescuing our children from the obesity epidemic. New York: Basic Books. ↵

- Eveleth, P. & Tanner, J. (1990). Worldwide variation in human growth (2nd edition). New York: Cambridge University Press. ↵

- Crooks, K. L., & Baur, K. (2007). Our sexuality (10th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth. ↵

- Dolgin, K. G. (2011). The adolescent: Development, relationships, and culture (13th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson. ↵

- Goodman, G. (2006). Acne and acne scarring: The case for active and early intervention. Australia Family Physicians, 35, 503- 504. ↵

- Euling, S. Y., Herman-Giddens, M.E., Lee, P.A., Selevan, S. G., Juul, A., Sorensen, T. I., Dunkel, L., Himes, J.H., Teilmann, G., & Swan, S.H. (2008). Examination of US puberty-timing data from 1940 to 1994 for secular trends: panel findings. Pediatrics, 121, S172-91. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2007-1813D. ↵

- Weir, K. (2016). The risks of earlier puberty. Monitor on Psychology, 47(3), 41-44. ↵

- Graber, J. A. (2013). Pubertal timing and the development of psychopathology in adolescence and beyond. Hormones and Behavior, 64, 262-289. ↵

- Weir, K. (2016). The risks of earlier puberty. Monitor on Psychology, 47(3), 41-44. ↵

- Weir, K. (2016). The risks of earlier puberty. Monitor on Psychology, 47(3), 41-44. ↵

- Mendle, J., Harden, K. P., Brooks-Gunn, J., & Graber, J. A. (2010). Development’s tortoise and hare: Pubertal timing, pubertal tempo, and depressive symptoms in boys and girls. Developmental Psychology, 46,1341–1353. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020205 ↵

- Dudovitz, R.N., Chung, P.J., Elliott, M.N., Davies, S.L., Tortolero, S,… Baumler, E. (2015). Relationship of Age for Grade and Pubertal Stage to Early Initiation of Substance Use. Preventing Chronic Disease, 12:150234. http://dx.doi.org/10.5888/pcd12.150234. ↵

- National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). (2020). The teen brain: 7 things to know. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/the-teen-brain-7-things-to-know ↵

- National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). I’m so stressed out! Fact sheet. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/so-stressed-out-fact-sheet ↵

- Romeo, R.D. (2013). The teenage brain: The stress response and the adolescent brain. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 22(2), 140-145. ↵

- Casey, B. J., Tottenham, N., Liston, C., & Durston, S. (2005). Imaging the developing brain: what have we learned about cognitive development? Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 9(3), 104–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2005.01.011 ↵

- Hartley, C.A. & Somerville, L.H. (2015). The neuroscience of adolescent decision-making. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 5, 108-115. ↵

- Steinberg, L. (2008) A social neuroscience perspective on adolescent risk-taking. Developmental Review, 28:78-106. ↵

- Giedd, J. N. (2015). The amazing teen brain. Scientific American, 312(6), 32-37. ↵

- Dobbs, D. (2012). Beautiful brains. National Geographic, 220(4), 36. ↵

- Weir, K. (2015). Marijuana and the developing brain. Monitor on Psychology, 46(10), 49-52. ↵

- Dobbs, D. (2012). Beautiful brains. National Geographic, 220(4), 36. ↵

- Giedd, J. N. (2015). The amazing teen brain. Scientific American, 312(6), 32-37. ↵

- Steinberg, L. (2008) A social neuroscience perspective on adolescent risk-taking. Developmental Review, 28:78-106. ↵