Nutrition in Infancy and Toddlerhood

Naomi H. Dan Karami; Diana Lang; Martha Lally; and Suzanne Valentine-French

Proper nutrition in a supportive environment is vital for an infant’s healthy growth and development. From birth to 1 year, infants triple their weight and increase their height by half, and this growth requires proper nutrition. Breast milk is typically considered the ideal diet for newborns due to the nutritional makeup of colostrum and subsequent breastmilk production. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends that infants be fed breast milk for the first 6 months of life and to introduce foods with breast milk until a child is 12 months old or older.[1] The World Health Organization[2] recommends:

- initiation of breastfeeding within one hour of birth,

- exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months of life, and

- introduction of solid foods at six months together with continued breast milk up to two years of age or beyond.

“Breastfeeding” or “being fed breast milk?” Many options and interpretations

Recommendations for “breastfeeding” can have different meanings. For instance, historically, breastfeeding has been defined as an infant snuggled on a mother’s breast and drinking milk directly from her breast. However, many options exist for feeding breast milk to an infant. A woman who has given birth can feed an infant directly from her breast, milk can be expressed from a breast and fed through a bottle,[3] breast milk can be purchased from a bank[4], and people can take hormones to stimulate lactation to produce breast milk.[5]

When “breastfeeding” or “feeding breast milk” may not be an option

There are occasions when caregivers may be unable to breastfeed or provide breast milk for a variety of health, social, and emotional reasons. For example, breastfeeding may not be an option:

- when the nursing mother has a transmissible disease such as active, untreated tuberculosis or HIV,

- when the nursing mother is receiving chemotherapy or radiation therapy,

- when the nursing mother is addicted to drugs or taking any medication that may be harmful to the baby (including some types of birth control),

- when there are attachment issues between the primary caregiver and baby,

- when the mother or the baby is in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) after the delivery process, or

- when the nursing mother does not produce enough breast-milk[6]

- However, as we learned above, breast milk can be purchased from a bank, which can remediate some of these complications.

Benefits of breast milk

Colostrum, the milk produced during pregnancy and just after birth, has been described as “liquid gold” (Figure 1). Colostrum is packed with nutrients and other important substances that help the infant build up his or her immune system. Babies will typically get all the nutrition they need through colostrum during the first few days of life.[7] Breast milk changes by the third to fifth day after birth, becoming much thinner, but containing just the right amount of fat, sugar, water, and proteins to support overall physical and neurological development.

Breast milk also provides a source of iron more easily absorbed in the body than the iron found in dietary supplements, it typically provides resistance against many diseases, infants typically more easily digest it than formula, and it helps babies make a transition to solid foods more easily. Infants need high fat content due to the process of myelination, which requires fat to insulate the neurons.

Benefits of feeding from the breast

One early argument given to promote the practice of feeding from the breast (when health issues are not an issue) is that it promotes bonding and healthy emotional development for infants. However, research shows that breastfed and bottle-fed infants can adjust equally well emotionally.[8] Skin-to-skin contact is important for bonding and emotional development regardless of how infants receive their milk.

Research also demonstrates that infants who were fed breast milk tend to have lower rates of childhood leukemia, asthma, obesity, type 1 and 2 diabetes, and SIDS. In addition, mothers who breast feed tend to have lower rates of breast and ovarian cancer, type 2 diabetes, and high blood pressure.[9] And, breastfeeding stimulates contractions in the uterus of the woman who gave birth which helps it regain its normal size.

Watch this video from the Psych SciShow “Bad Science: Breastmilk and Formula” to learn about research related to both breastfeeding and formula-feeding.

To learn more about breastfeeding, visit this resource from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Resources: Your Guide to Breastfeeding.

Visit Kids Health on Breastfeeding vs. Formula Feeding to learn more about the benefits and challenges of each. Click on the speaker icon to listen to the narration of the article if you would like.

Meta-analyses have revealed that breastfeeding is connected to advantages with cognitive development.[10] Low birth weight infants had greater benefits from breastfeeding than did normal-weight infants in a meta-analysis of twenty controlled studies examining the overall impact of breastfeeding.[11] This meta-analysis showed that breastfeeding may provide nutrients required for rapid development of the immature brain and be connected to more rapid or better development of neurologic function. The studies also showed that a longer duration of breastfeeding was accompanied by greater differences in cognitive development between breastfed and formula-fed children. Whereas normal-weight infants showed a 2.66-point difference, low-birth-weight infants showed a 5.18-point difference in IQ compared with weight-matched, formula-fed infants.[12] These studies suggest that nutrients present in breast milk may have a significant effect on neurologic development in both premature and full-term infants. Starting good nutrition practices early on can help children develop healthy dietary patterns and infants need proper nutrients to fuel their rapid physical growth. Without proper nutrition, infants are at risk for malnutrition, which can result in physical, cognitive, emotional, and social consequences.

A Historic Look at Breastfeeding

The use of wet nurses, or lactating women, hired to nurse others’ infants, during the middle ages eventually declined, and mothers increasingly breastfed their own infants in the late 1800s. In the early part of the 20th century, breastfeeding began to go through another decline, and by the 1950s it was practiced less frequently by middle class, more affluent mothers as formula began to be viewed as superior to breast milk. In the late 1960s and 1970s, there was again a greater emphasis placed on natural childbirth and breastfeeding and the benefits of breastfeeding were more widely publicized. Gradually, rates of breastfeeding began to climb, particularly among middle-class educated mothers who received the strongest messages to breastfeed. In the 1960s, formula companies led campaigns in developing countries to encourage mothers to feed their babies infant formula. Many mothers felt that formula would be superior to breast milk and began using formula. The use of formula can be healthy under conditions in which there is adequate, clean water with which to mix the formula and adequately sanitize bottles and nipples. However, in many countries, such conditions were not available and babies often were given diluted, contaminated formula that made them sick with diarrhea and leading to dehydration. These conditions continue today in some developing countries and hospitals in those developing countries prohibit the distribution of formula samples to new mothers in efforts to get them to rely on breastfeeding. Many of mothers in these countries do not understand the benefits of breastfeeding and have to be encouraged and supported to promote this practice.

Global Considerations and Malnutrition

According to WHO, malnutrition is defined as the low intake of nutrients or the excessive intake of nutrients, which can cause undernutrition or overweight/obesity respectively. Malnutrition is classified into four categories: wasting, stunting, underweight, and micronutrient deficiencies(Figure 2).[13]

Wasting occurs when a person has limited food intake with limited nutrients. A child who experiences wasting has a higher risk of dying if left untreated. It is often measured when the child has a lower weight for their height. Stunting, on the other hand, is measured when there is low height for age. It causes by the lack of enough and properly balanced diet for a long period due to poverty, maternal health and nutrition, frequent illnesses, inappropriate feeding, and care from a younger age. An underweight child is a child that has a low weight for their age. They often can be stunted, wasted, or both.[14]

Malnutrition is a significant public health problem in several developing countries. In Niger, a country in West Africa with the youngest population, malnutrition persists across the country. It is reported that about 15.0% of children were classified as acutely malnourished in 2018. About 47.8% of children are stunted due to malnutrition. Stunting negatively affects cognitive and physical development, which also harms the country’s economy. It is projected that stunting will increase by 44 % by 2025 as the population in Niger continues to grow.[15]

Find out more statistics and recommendations for breastfeeding at the WHO’s 10 facts on breastfeeding. You can also learn about efforts to promote breastfeeding in Peru: “Protecting Breastfeeding in Peru”.

Breastfeeding could save the lives of millions of infants each year, according to the WHO, yet fewer than 40 percent of infants across the world are breastfed exclusively for the first 6 months of life. Because of the great benefits of breastfeeding, WHO, United Nations Children’s Fund, formerly United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF), and other national organizations are working together to step up support for breastfeeding across the world.

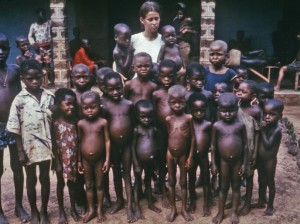

Children in developing countries and countries experiencing the harsh conditions of war are at risk for two major types of malnutrition. Infantile marasmus refers to starvation due to a lack of calories and protein. Children who do not receive adequate nutrition lose fat and muscle until their bodies can no longer function. Babies who are breastfed are much less at risk of malnutrition than those who are bottle-fed. After weaning, children who have diets deficient in protein may experience kwashiorkor, or the “disease of the displaced child,” often occurring after another child has been born and taken over breastfeeding. This results in a loss of appetite and swelling of the abdomen as the body begins to break down the vital organs as a source of protein.

Milk Anemia in the United States

Many infants suffer from milk anemia, a condition in which milk consumption leads to a lack of iron in the diet. The body gets iron through certain foods. Toddlers who drink too much cow’s milk may also become anemic if they are not eating other healthy foods that have iron. This can be due to the practice of giving toddlers milk as a pacifier when resting, riding, walking, and so on. Appetite declines somewhat during toddlerhood and a small amount of milk (especially with added chocolate syrup) can easily satisfy a child’s appetite for many hours. The calcium in milk interferes with the absorption of iron in the diet as well. There is also a link between iron deficiency anemia and diminished mental, motor, and behavioral development. In the second year of life, iron deficiency can be prevented by the use of a diversified diet that is rich in sources of iron and vitamin C, limiting cow’s milk consumption to less than 24 ounces per day, and providing a daily iron-fortified vitamin.[16]

Introducing Solid Foods

Breast milk or formula is the only food a newborn needs, and the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months after birth. Solid foods can be introduced from around six months onward when babies develop stable sitting and oral feeding skills but should be used only as a supplement to breast milk or formula. By six months, the gastrointestinal tract has matured, solids can be digested more easily, and allergic responses are less likely. The infant is also likely to develop teeth around this time, which aids in chewing solid food. Iron-fortified infant cereal, made of rice, barley, or oatmeal, is typically the first solid introduced due to its high iron content. Cereals can be made of rice, barley, or oatmeal (Figure 3). Generally, salt, sugar, processed meat, juices, and canned foods should be avoided.

Though infants usually start eating solid foods between 4 and 6 months of age, more and more solid foods are consumed by a growing toddler. Pediatricians recommended introducing foods one at a time, and for a few days, in order to identify any potential food allergies. Toddlers may be picky at times, but it remains important to introduce a variety of foods and offer food with essential vitamins and nutrients, including iron, calcium, and vitamin D.

Nutrition

Breast milk is considered the ideal diet for newborns if/when the milk is free from drug and disease exposure (see above, When “breastfeeding” or “feeding breast milk” may not be an option). Colostrum, the first breast milk produced during pregnancy and just after birth has been described as “liquid gold.” [17] It is very rich in nutrients and antibodies. Breast milk changes by the third to fifth day after birth, becoming much thinner, but containing just the right amount of fat, sugar, water and proteins to support overall physical and neurological development. For most babies, breast milk is also easier to digest than formula. Formula fed infants experience more diarrhea and upset stomachs. The absence of antibodies in formula often results in a higher rate of ear infections and respiratory infections. Children who are breastfed have lower rates of childhood leukemia, asthma, obesity, type 1 and 2 diabetes, and a lower risk of SIDS. The USDHHS recommends that mothers breast feed their infants until at least 6 months of age and that breast milk be used in the diet throughout the first year or two.

Several recent studies have reported that it is not just babies that benefit from breastfeeding. Breastfeeding stimulates contractions in the uterus to help it regain its normal size, and women who breastfeed are more likely to space their pregnancies further apart. Mothers who breastfeed are at lower risk of developing breast cancer,[18] especially among higher risk racial and ethnic groups.[19][20] Women who breastfeed have lower rates of ovarian cancer,[21] reduced risk for developing Type 2 diabetes,[22][23] and rheumatoid arthritis.[24] In most studies these benefits have been seen in women who breastfeed longer than 6 months.

Mothers can certainly continue to provide breast milk to their babies by expressing and freezing the milk to be bottle fed at a later time or by being available to their infants at feeding time. However, some mothers find that after the initial encouragement they receive in the hospital to breastfeed, the outside world is less supportive of such efforts. Some workplaces support breastfeeding mothers by providing flexible schedules and welcoming infants, but many do not. In addition, not all women may be able to breastfeed. Women with HIV are routinely discouraged from breastfeeding as the infection may pass to the infant. Similarly, women who are taking certain medications or undergoing radiation treatment may be told not to breastfeed.[25]

In addition to the nutritional benefits of breastfeeding, breast milk is free. Anyone who has priced formula recently can appreciate this added incentive to breastfeeding. One early argument given to promote the practice of breastfeeding was that it promoted bonding and healthy emotional development for infants. However, this does not seem to be the case. Breastfed and bottle-fed infants adjust equally well emotionally.[26][/footnote] This is good news for mothers who may be unable to breastfeed for a variety of reasons and for fathers who might feel left out.

When to Introduce More Solid Foods: Solid foods should not be introduced until the infant is ready. According to The Clemson University Cooperative Extension,[27] some things to look for include that the infant:

- can sit up without needing support,

- can hold its head up without wobbling,

- shows interest in foods others are eating,

- is still hungry after being breastfed or formula fed,

- is able to move foods from the front to the back of the mouth, and

- is able to turn away when they have had enough.

For many infants who are 4 to 6 months of age, breast milk or formula can be supplemented with more solid foods. The first semi-solid foods that are introduced are iron-fortified infant cereals mixed with breast milk or formula. Typically rice, oatmeal, and barley cereals are offered as a number of infants are sensitive to more wheat based cereals. Finger foods such as toast squares, cooked vegetable strips, or peeled soft fruit can be introduced by 10-12 months. New foods should be introduced one at a time, and the new food should be fed for a few days in a row to allow the baby time to adjust to the new food. This also allows parents time to assess if the child has a food allergy. Foods that have multiple ingredients should be avoided until parents have assessed how the child responds to each ingredient separately. Foods that are sticky (such as peanut butter or taffy), cut into large chunks (such as cheese and harder meats), and firm and round (such as hard candies, grapes, or cherry tomatoes) should be avoided as they are a choking hazard. Honey and Corn syrup should be avoided as these often contain botulism spores. In children under 12 months this can lead to death.[28]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022a). Breastfeeding: Frequently asked questions (FAQS). https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/faq/#howlong ↵

- World Health Organization. (2018) Breastfeeding. https://www.who.int/news-room/facts-in-pictures/detail/breastfeeding ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021a). Nutrition. https://www.cdc.gov/nutrition/InfantandToddlerNutrition/breastfeeding/pumping-breast-milk.html ↵

- Human Milk Banking: Association of North America. (2022). Milk banking frequent questions. https://www.hmbana.org/about-us/frequent-questions.html ↵

- Mayo Clinc. (2021). Infant and toddler health. https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/infant-and-toddler-health/expert-answers/induced-lactation/faq-20058403 ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022). Breastfeeding: Breastfeeding and special circumstances. https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/breastfeeding-special-circumstances/Contraindications-to-breastfeeding.html ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021b). What to expect while breastfeeding. https://www.cdc.gov/nutrition/InfantandToddlerNutrition/breastfeeding/what-to-expect.html ↵

- Fergusson, & Woodward. (1999). Breast feeding and later psychosocial adjustment. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology, 13(2), 144–157. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-3016.1999.00167.x ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021c). Division of Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity. https://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpao/features/breastfeeding-benefits/index.html ↵

- Anderson, J. W., Johnstone, B. M., & Remley, D. T. (1999). Breast-feeding and cognitive development: a meta-analysis. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 70(4), 525–535. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/70.4.525 ↵

- Anderson, J. W., Johnstone, B. M., & Remley, D. T. (1999). Breast-feeding and cognitive development: a meta-analysis. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 70(4), 525–535. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/70.4.525 ↵

- Anderson, J. W., Johnstone, B. M., & Remley, D. T. (1999). Breast-feeding and cognitive development: a meta-analysis. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 70(4), 525–535. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/70.4.525 ↵

- World Health Organization. (2021). Malnutrition. https://www.who.int/health-topics/malnutrition#tab=tab_2 ↵

- World Health Organization. (2021). Malnutrition. https://www.who.int/health-topics/malnutrition#tab=tab_2 ↵

- UNICEF NIGER (2021). Nutrition. https://www.unicef.org/niger/nutrition ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (1998). Recommendations to prevent and control iron deficiency in the United States. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00051880.htm ↵

- United States Department of Health and Human Services. (2012). A profile of older Americans: 2012. http://www.aoa.gov/Aging_Statistics/Profile/2012/docs/2012profile.pdf ↵

- Islami, F., Liu, Y., Jemal, A., Zhou, J., Weiderpass, E., Colditz, G…Weiss, M. (2015). Breastfeeding and breast cancer risk by receptor status – a systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of Oncology, 26, 2398-2407. ↵

- Islami, F., Liu, Y., Jemal, A., Zhou, J., Weiderpass, E., Colditz, G…Weiss, M. (2015). Breastfeeding and breast cancer risk by receptor status – a systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of Oncology, 26, 2398-2407. ↵

- Redondo, C. M., Gago-Domínguez, M., Ponte, S. M., Castelo, M. E., Jiang, X., García, A. A., Fernández, M. P., Tomé, M. A., Fraga, M., Gude, F., Martínez, M. E., Garzón, V. M., Carracedo, Á., & Castelao, J. E. (2012). Breast feeding, parity and breast cancer subtypes in a Spanish cohort. PloS One, 7(7), e40543. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0040543 ↵

- Titus-Ernstoff, L., Rees, J. R., Terry, K. L., & Cramer, D. W. (2010). Breast-feeding the last born child and risk of ovarian cancer. Cancer Causes & Control: CCC, 21(2), 201–207. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-009-9450-8 ↵

- Schwarz, E. B., Brown, J. S., Creasman, J. M., Stuebe, A., McClure, C. K., Van Den Eeden, S. K., & Thom, D. (2010). Lactation and maternal risk of type 2 diabetes: a population-based study. The American Journal of Medicine, 123(9), 863.e1-6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2010.03.016 ↵

- Gunderson, E. P., Hurston, S. R., Ning, X., Lo, J. C., Crites, Y., Walton, D., Dewey, K. G., Azevedo, R. A., Young, S., Fox, G., Elmasian, C. C., Salvador, N., Lum, M., Sternfeld, B., Quesenberry, C. P., Jr, & Study of Women, Infant Feeding and Type 2 Diabetes After GDM Pregnancy Investigators. (2015). Lactation and progression to type 2 diabetes mellitus after gestational diabetes mellitus: A prospective cohort Study. Annals of Internal Medicine, 163(12), 889–898. https://doi.org/10.7326/M15-0807 ↵

- Karlson, E.W., Mandl, L.A., Hankison, S. E., & Grodstein, F. (2004). Do breast-feeding and other reproductive factors influence future risk of rheumatoid arthritis? Arthritis & Rheumatism, 50 (11), 3458-3467. ↵

- United States Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Women’s Health (2011). Your guide to breast feeding. Washington D.C. ↵

- [footnote]Fergusson, & Woodward. (1999). Breast feeding and later psychosocial adjustment. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology, 13(2), 144–157. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-3016.1999.00167.x ↵

- Clemson University Cooperative Extension. (2014). Introducing Solid Foods to Infants. http://www.clemson.edu/extension/hgic/food/nutrition/nutrition/life_stages/hgic4102.html ↵

- Clemson University Cooperative Extension. (2014). Introducing Solid Foods to Infants. http://www.clemson.edu/extension/hgic/food/nutrition/nutrition/life_stages/hgic4102.html ↵