Physical Development in Early Adulthood

Diana Lang; Nick Cone; Margaret Clark-Plaskie; Laura Overstreet; Martha Lally; Suzanne Valentine-French; and Wikimedia Contributors

The Physiological Peak

People in their twenties and thirties are considered young adults. If you are in your early twenties, you are probably at the peak of your physiological development. Your body has completed its growth, though your brain is still developing (as explained in the previous module on adolescence). Physically, you are in the “prime of your life” as your reproductive system, motor ability, strength, and lung capacity are operating at their best. However, these systems will start a slow, gradual decline so that by the time you reach your mid to late 30s, you will begin to notice signs of aging. This includes a decline in your immune system, your response time, and in your ability to recover quickly from physical exertion. For example, you may have noticed that it takes you quite some time to stop panting after running to class or taking the stairs. But, remember that both nature and nurture continue to influence development. Getting out of shape is not an inevitable part of aging; it is probably due to the fact that you have become less physically active and have experienced greater stress. The good news is that there are things you can do to combat many of these changes. So keep in mind, as we continue to discuss the lifespan, that some of the changes we associate with aging can be prevented or turned around if we adopt healthier lifestyles.

In fact, research shows that the habits we establish in our twenties are related to certain health conditions in middle age, particularly the risk of heart disease. What are healthy habits that young adults can establish now that will prove beneficial in later life? Healthy habits include maintaining a lean body mass index, moderate alcohol intake, a smoke-free lifestyle, a healthy diet, and regular physical activity. When experts were asked to name one thing they would recommend young adults do to facilitate good health, their specific responses included: weighing self often, learning to cook, reducing sugar intake, developing an active lifestyle, eating vegetables, practicing portion control, establishing an exercise routine), and finding a job you love.[1]

Being overweight or obese is a concern in early adulthood. Medical research shows that Americans with moderate weight gain from early to middle adulthood have significantly increased risks of major chronic disease and mortality.[2] Given the fact that Americans tend to gain about one to two pounds per year from early to middle adulthood, developing healthy nutrition and exercise habits across adulthood is extremely important.[3]

Health in Early Adulthood

Obesity

Although at the peak of physical health, a concern for early adults is the current rate of obesity. Body mass index (BMI), expressed as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared (kg/m2), is commonly used to classify overweight (BMI 25.0–29.9), obesity (BMI greater than or equal to 30.0), and extreme obesity (BMI greater than or equal to 40.0). The CDC[4] also indicated that one’s 20s are the prime time to gain weight as the average person gains one to two pounds per year from early adulthood into middle adulthood. The American obesity crisis is also reflected worldwide.[5]

Causes of Obesity

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC),[6] obesity originates from a complex set of contributing factors, including one’s environment, behavior, and genetics. Societal factors include culture, education, food marketing and promotion, the quality of food, and the physical activity environment available. Behaviors leading to obesity include diet, the amount of physical activity, and medication use. Lastly, there does not appear to be a single gene responsible for obesity. Rather, research has identified variants in several genes that may contribute to obesity by increasing hunger and food intake. Another genetic explanation is the mismatch between today’s environment and “energy-thrifty genes” that multiplied in the distant past, when food sources were unpredictable. The genes that helped our ancestors survive occasional famines are now being challenged by environments in which food is plentiful all the time. Overall, obesity most likely results from complex interactions among the environment and multiple genes.

Obesity Health Consequences

Obesity is considered to be one of the leading causes of death in the United States and worldwide. According to the CDC[7] compared to those with a normal or healthy weight, people who are obese are at increased risk for many serious diseases and health conditions including:

- All-causes of death (mortality)

- High blood pressure (Hypertension)

- High LDL cholesterol, low HDL cholesterol, or high levels of triglycerides (Dyslipidemia)

- Type 2 diabetes

- Coronary heart disease

- Stroke

- Gallbladder disease

- Osteoarthritis (a breakdown of cartilage and bone within a joint)

- Sleep apnea and breathing problems

- Some cancers (endometrial, breast, colon, kidney, gallbladder, and liver)

- Low quality of life

- Mental illness such as clinical depression, anxiety, and other disorders

- Body pain and difficulty with physical functioning

This video explains how the brain continues to develop into adulthood:

You can view the transcript for “When Does Your Brain Stop Developing?” here (opens in new window).

A Healthy, but Risky Time

Early adulthood tends to be a time of relatively good health. For instance, in the United States, adults ages 18-44 have the lowest percentage of physician office visits than any other age group, younger or older. However, early adulthood seems to be a particularly risky time for violent deaths (rates vary by gender, race, and ethnicity). The leading causes of death for both age groups 15-24 and 25-34 in the U.S. are unintentional injury, suicide, and homicide. Cancer and heart disease follow as the fourth and fifth top causes of death among young adults.[8]

Substance Use, Abuse, and Risky Behaviors

Rates of violent death are influenced by substance use which tends to peak during emerging and early adulthood. Drugs impair judgment, reduce inhibitions, and alter mood, all of which can lead to dangerous behavior. Reckless driving, violent altercations, and forced sexual encounters are some examples. Drug and alcohol use increase the risk of sexually transmitted infections because people are more likely to engage in risky sexual behavior when under the influence. This includes having sex with someone who has had multiple partners, having anal sex without the use of a condom, having multiple partners, or having sex with someone whose history is unknown. Lastly, as previously discussed, drugs and alcohol ingested during pregnancy have a teratogenic effect on the developing embryo and fetus.

Overdose deaths involving prescription opioids more than quadrupled from 1999 through 2016 followed by significant declines reported in both 2018 and 2019, and then an increase in 2020.[9][10]

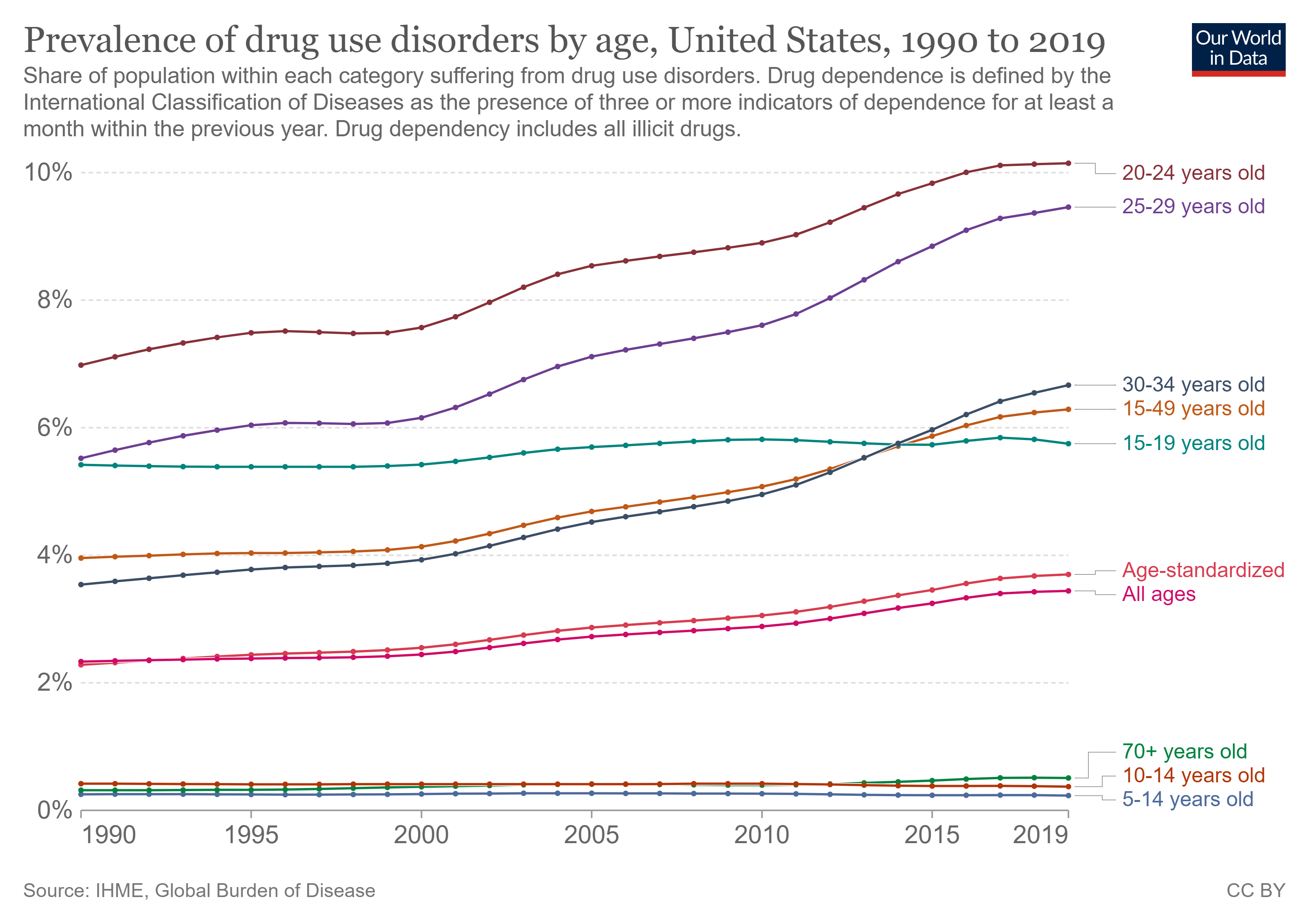

Overall, the prevalence of drug use disorders is highest in people in their twenties. For example, an estimated 464,000 young adults aged 18 to 25 in 2018 initiated prescription pain reliever misuse in 2018, or an average of about 1,300 young adults each day who initiated pain reliever misuse. The number of young adults in 2018 who initiated pain reliever misuse was lower than the numbers in 2015 and 2016, but it was similar to the number in 2017.[11]

Unlike the patterns for cigarette, alcohol, and marijuana use, the majority of the people in 2018 who initiated pain reliever misuse were aged 26 or older.[12]

Approximately 2 in 5 young adults aged 18 to 25 in 2018 (38.7 percent) were past year users of illicit drugs. This percentage corresponds to about 13.2 million young adults who used illicit drugs in the past year. The percentage of young adults in 2018 who used illicit drugs in the past year was similar to the percentages in 2015 to 2017.[13]

The higher prevalence of substance use disorders in people in their twenties (or sometimes in their late teens) is consistent across most countries and is typically related to risky behaviors.

Alcohol Use

The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA)[14] defines binge drinking when blood alcohol concentration levels reach 0.08 g/dL. This typically occurs after four drinks for women and five drinks for men in approximately two hours. According to the NIAAA[15] “Binge drinking poses serious health and safety risks, including car crashes, drunk-driving arrests, sexual assaults, and injuries. Over the long term, frequent binge drinking can damage the liver and other organs,” (p. 1).

Alcohol and College Students

The role alcohol plays in predicting acquaintance rape on college campuses is of particular concern. “Alcohol use in one the strongest predictors of rape and sexual assault on college campuses.” [16] Krebs et al.[17] found that more than 80% of sexual assaults on college campuses involved alcohol. Many college students view perpetrators who were drinking as less responsible, and victims who were drinking as more responsible for the assaults.[18] However, in most states, the legal ability to give consent requires that individuals not be under the influence of alcohol or other substances.

Factors Affecting College Students’ Drinking

Several factors associated with college life affect a student’s involvement with alcohol.[19] These include the pervasive availability of alcohol, inconsistent enforcement of underage drinking laws, unstructured time, coping with stressors, and limited interactions with parents, caregivers, and other adults. Due to social pressures to conform and expectations when entering college, the first six weeks of freshman year are an especially susceptible time for students. Additionally, more drinking occurs in colleges with active Greek systems and athletic programs. Alcohol consumption is lowest among students living with their families and commuting, while it is highest among those living in fraternities and sororities.

College Strategies to Curb Drinking

Strategies to address college drinking involve the individual-level and campus community as a whole. Identifying at-risk groups, such as first year students, members of fraternities and sororities, and athletes has proven helpful in changing students’ knowledge, attitudes, and behavior regarding alcohol.[20] Interventions include education and awareness programs, as well as intervention by health professionals. At the college-level, reducing the availability of alcohol has proven effective by decreasing both consumption and negative consequences.

Nicotine Use

In 2018, an estimated 6.5 million young adults aged 18 to 25 smoked cigarettes in the past month. This number of young adults who were current cigarette smokers corresponds to about one fifth of young adults (19.1 percent). The percentage of young adults who were current cigarette smokers in 2018 was lower than the percentages in 2002 to 2017.

According to the CDC[21], the use of e-cigarettes (also referred to as vaping, e-hookahs, vape pens, tank systems, mods, and electronic nicotine delivery systems) reached the highest prevalence in 2019 and is now slowly declining. E-cigarettes are unsafe for kids, teens, and young adults because they can contain other harmful substances in addition to nicotine, which is highly addictive, and can harm brain development at this age. Young people who use e-cigarettes may be more likely to smoke cigarettes in the future.[22] In addition, serious and fatal lung injuries are linked to e-cigarette use due to the combinations of nicotine, tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), cannabinoid (CBD) oils, and other substances, flavorings, and additives.

Sexually Transmitted Infections: Sexually transmitted infections (STIs), also referred to as sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) or venereal diseases (VDs), are illnesses that have a significant probability of transmission by means of sexual behavior, including vaginal intercourse, anal sex, and oral sex. Some STIs can also be contracted by sharing intravenous drug needles with an infected person, as well as through childbirth or breastfeeding.

Common STIs include:

- chlamydia;

- herpes (HSV-1 and HSV-2);

- human papillomavirus (HPV);

- gonorrhea;

- syphilis;

- trichomoniasis;

- HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) and AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome).

The most effective way to prevent transmission of STIs is to practice safe sex by completely avoiding direct contact of skin and/or fluids which can lead to transfer with infected partners. Proper use of safe-sex supplies (such as condoms, gloves, or dental dams) reduces contact and risk and can be effective in limiting exposure; however, some disease transmission may occur even with these barriers.

Sexuality

Human sexuality refers to people’s sexual interest in and attraction to others, as well as their capacity to have erotic experiences and responses. Sexuality may be experienced and expressed in a variety of ways, including thoughts, fantasies, desires, beliefs, attitudes, values, behaviors, practices, roles, and relationships. These may manifest themselves in biological, physical, emotional, social, or spiritual aspects. The biological and physical aspects of sexuality largely concern the human reproductive functions, including the human sexual-response cycle and the basic biological drive that exists in all species. Emotional aspects of sexuality include bonds between individuals that are expressed through profound feelings or physical manifestations of love, trust, and care. Social aspects deal with the effects of human society on one’s sexuality, while spirituality concerns an individual’s spiritual connection with others through sexuality. Sexuality also impacts, and is impacted by cultural, political, legal, philosophical, moral, ethical, and religious aspects of life.

The Brain and Sex

The brain is the structure that translates the nerve impulses from the skin into pleasurable sensations. It controls nerves and muscles used during sexual behavior. The brain regulates the release of hormones, which are believed to be the physiological origin of sexual desire. The cerebral cortex, which is the outer layer of the brain that allows for thinking and reasoning, is believed to be the origin of sexual thoughts and fantasies. Beneath the cortex is the limbic system, which consists of the amygdala, hippocampus, cingulate gyrus, and septal area. These structures are where emotions and feelings are believed to originate, and are important for sexual behavior.

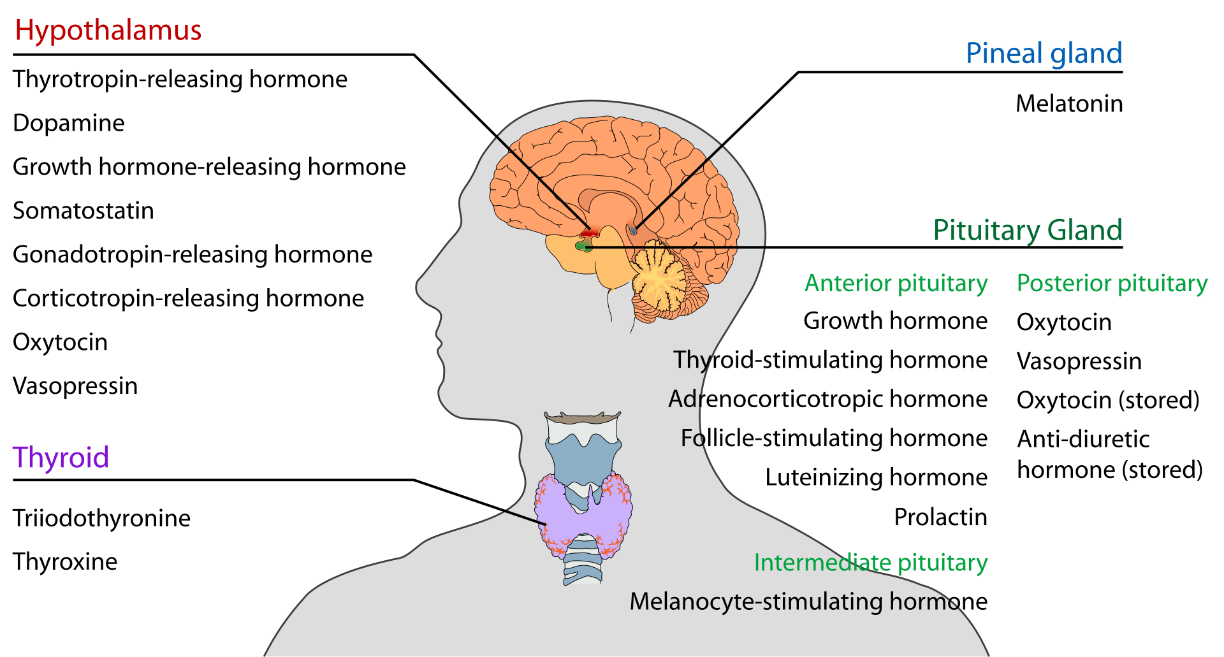

The hypothalamus is the most important part of the brain for sexual functioning. This is the small area at the base of the brain consisting of several groups of nerve-cell bodies that receives input from the limbic system. Studies with lab animals have shown that destruction of certain areas of the hypothalamus causes complete elimination of sexual behavior. One of the reasons for the importance of the hypothalamus is that it controls the pituitary gland, which secretes hormones that control the other glands of the body.

Hormones

Several important sexual hormones are secreted by the pituitary gland. Oxytocin, also known as the hormone of love, is released during sexual intercourse when an orgasm is achieved. Oxytocin is also released in females when they give birth or are breast feeding; it is believed that oxytocin is involved with maintaining close relationships. Both prolactin and oxytocin stimulate milk production in females. Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) is responsible for ovulation in females by triggering egg maturity; it also stimulates sperm production in males. Luteinizing hormone (LH) triggers the release of a mature egg in females during the process of ovulation.

Testosterone appears to be a major contributing factor to sexual motivation. Vasopressin is involved in the male arousal phase, and the increase of vasopressin during erectile response may be directly associated with increased motivation to engage in sexual behavior.

Estrogen and progesterone typically regulate motivation to engage in sexual behavior for females, with estrogen increasing motivation and progesterone decreasing it. The levels of these hormones rise and fall throughout a female’s menstrual cycle. Research suggests that testosterone, oxytocin, and vasopressin are also implicated in female sexual motivation in similar ways as they are in males, but more research is needed to understand these relationships.

The Sexual Response Cycle is a model that describes the physiological responses that take place during sexual activity. According to Kinsey, Pomeroy, and Martin,[23] the cycle consists of four phases: excitement, plateau, orgasm, and resolution. The excitement phase is the phase in which the intrinsic (inner) motivation to pursue sex arises. The plateau phase is the period of sexual excitement with increased heart rate and circulation that sets the stage for orgasm. Orgasm is the release of tension, and the resolution period is the unaroused state before the cycle begins again.

Sexual motivation, often referred to as libido, is a person’s overall sexual drive or desire for sexual activity. This motivation is determined by biological, psychological, and social factors. In most mammalian species, sex hormones control the ability to engage in sexual behaviors. However, sex hormones do not directly regulate the ability to copulate in primates (including humans); rather, they are only one influence on the motivation to engage in sexual behaviors. Social factors, such as work and family also have an impact, as do internal psychological factors like personality and stress. Hormones, medical conditions, medications, lifestyle stress, pregnancy, and relationship issues may also affect sex drive.

Sexual Responsiveness

People tend to reach their peak of sexual responsiveness at different ages. Sexual arousal can easily occur in response to physical stimulation or fantasizing. Sexual responsiveness tends to decline in the late twenties and into the thirties although they may continue to be sexually active throughout adulthood. Over time, individuals may require more intense stimulation in order to become aroused.

Sexlessness

There has been a sharp increase in the number of individuals ages 18 to 35 who report not having sexual intercourse (sexlessness) in the prior year and it continued into 2021.[24] This research shows there have been at least two separate trends related to the increase in sexlessness: one is that people are delaying marriage and the other is the increasing sexlessness among individuals who have never been married. For additional information, visit the 2021 General Social Survey).

- Parker-Pope, T. (2016, October 17). The 8 health habits experts say you need in your 20s. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2016/10/16/well/live/health-tips-for-your-20s.html ↵

- Zheng, Y., Manson, J. E., Yuan, C., Liang, M. H., Grodstein, F., Stampfer, M. J., Willett, W. C., & Hu, F. B. (2017). Associations of weight gain from early to middle adulthood with major health outcomes later in life. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association, 318(3), 255–269. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.7092 ↵

- Nichols, H. (2017, July 18). Weight gain in early adulthood linked to health risks later in life. Medical News Today. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/318480 ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016). Adult obesity causes and consequences. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/obesity/adult/causes.html ↵

- Wighton, K. (2016). World’s obese population hits 640 million, according to largest ever study. Imperial College. http://www3.imperial.ac.uh/newsandeventspggrp/imperialcollege/newssummary/news_311-3-2016-22-34-39 ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016). Adult obesity causes and consequences. http://www.cdc.gov/obesity/adult/causes.html ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016). Adult obesity causes and consequences. http://www.cdc.gov/obesity/adult/causes.html ↵

- Centers for Disease Control. (2022). Leading causes of death. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/leading-causes-of-death.htm ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prescription Opioids Overview. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/data/prescribing/overview.html ↵

- CDC WONDER. Multiple Cause of Death 1999-2020. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center on Health Statistics. https://wonder.cdc.gov/ ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2019). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. PEP19-5068, NSDUH Series H-54). Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/ ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2019). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. PEP19-5068, NSDUH Series H-54). Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/ ↵

- National Center for Drug Abuse Statistics. (2022). Drug Use Among Youth: Facts & Statistics. https://drugabusestatistics.org/teen-drug-use/ ↵

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. (2015). College Drinking. http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/CollegeFactSheet/CollegeFact.htm ↵

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. (2015). College Drinking. http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/CollegeFactSheet/CollegeFact.htm ↵

- Carroll, J. L. (2016). Sexuality now: Embracing diversity (5th ed.). Boston, MA: Cengage Learning. p.454 ↵

- Krebs, C., Lindquist, C., Warner, T., Fisher, B., & Martin, S. (2009). College women’s experiences with physically forced, alcohol or other drug-enabled, and drug-facilitated sexual assault before and since entering college. Journal of American College Health, 57(6), 639-649. ↵

- Untied, A. S., Orchowski, L. M., Mastroleo, N., & Gidycz, C. A. (2012). College students’ social reactions to the victim in a hypothetical sexual assault scenario: the role of victim and perpetrator alcohol use. Violence and Victims, 27(6), 957–972. https://doi.org/10.1891/0886-6708.27.6.957 ↵

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. (2015). College Drinking. http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/CollegeFactSheet/CollegeFact.htm ↵

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. (2015). College Drinking. http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/CollegeFactSheet/CollegeFact.htm ↵

- Centers for Disease Control. (2020, February 25). Outbreak of Lung Injury Associated with the Use of E-Cigarette, or Vaping, Products. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/severe-lung-disease.html ↵

- US Department of Health and Human Services. (2016). E-cigarette Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC. ↵

- Kinsey, A., Pomeroy, W.B., & Martin, C. E. (1948). Sexual behavior in the human male. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders. ↵

- Lyman Stone. (2021). Number 4 in 2021: More Faith, Less Sex: Why Are So Many Unmarried Young Adults Not Having Sex? Institute for Family Studies. https://ifstudies.org/blog/number-4-in-2021-more-faith-less-sex-why-are-so-many-unmarried-young-adults-not-having-sex ↵