Physical Development in Early Childhood

Diana Lang; Nick Cone; Laura Overstreet; Stephanie Loalada; Suzanne Valentine-French; Martha Lally; Julie Lazzara; and Jamie Skow

- Summarize physical growth during early childhood. Identify examples of gross and fine motor skill development in early childhood.

- Describe the growth of structures in the brain during early childhood.

- Identify nutritional concerns for children in early childhood.

- Describe sexual development in early childhood.

- Identify animism, egocentrism, and centration.

- Describe changes to attention and memory in early childhood.

- Apply Vygotsky theory to early childhood. Illustrate scaffolding. Explain private speech. Explain theory of mind.

- Describe language development in early childhood.

- Explain Erikson’s stages of psychosocial development for toddlers and children in early childhood.

- Contrast models of parenting styles.

- Examine concerns about childcare.

- Explain theory of self from Mead.

- Summarize theories of gender role development.

- Examine concerns about childhood stress and development.

The time between a child’s second and sixth birthday is a time of rich development as children grow rapidly in physical, cognitive, and social ways. Language skills continue to develop and improve that help children navigate their world and prepare to enter school. In fact, a child will go from producing approximately 50 words at age 2 to producing over 2000 words at age 6!

Children in early childhood are changing from intuitive problem solvers into more sophisticated logical problem solvers. Their cognitive skills are increasing at a rapid rate, despite their brain beginning to lose neurons through the process of synaptic pruning.

Children are also learning to navigate the social world around them. They are learning about themselves and beginning to develop their own self-concept, while at the same time becoming aware that other people have feelings, too. The development that happens in these four years greatly impacts the rest of the child’s life in many aspects.

Children in early childhood are physically growing at a rapid pace. A fun way to observe physical changes is to ask a child at the beginning of the early childhood period to take their left hand and use it to go over their head to touch their right ear. They cannot do it. Their body proportions are still built very much like an infant with a very large head and short appendages. By the time the child is five years old, their arms will have stretched, and their head is becoming smaller in proportion to the rest of their growing bodies. They can now accomplish the task easily.

Growth in early childhood

Children between the ages of 2 and 6 years tend to grow about 3 inches in height each year and gain about 4 to 5 pounds in weight each year. The average 6-year-old weighs about 46 pounds and is about 46 inches in height. Three-year-olds are very physically similar to toddlers with a large head, large stomach, short arms, and short legs. However, around age 3, children typically have all 20 of their primary teeth, and by around age 4, may have 20/20 vision. Many children take a daytime nap until around age 4 or 5, then sleep between 11 and 13 hours at night.

During early childhood, children start to lose some of their baby fat, making them appear less like a baby, and more like a child as they progress through this stage. By the time children reach age 6, their torsos have lengthened and body proportions have become more like those of adults. This is the growth pattern for children who receive adequate nutrition. Studies from many countries support the assertion that children tend to grow more slowly in low socioeconomic status areas, and thus are smaller.[1][2][3]

The growth rate between the ages of 2 and 6 is slower than that of infancy and is accompanied by a reduced appetite. This change can sometimes be surprising to parents and lead to the development of poor eating habits.

Brain Maturation

By two years of age the brain is about 75 percent of its adult weight. By age 6, it is at 95 percent of its adult weight. The development of myelin (myelination) and the development of new synapses (through the process of synaptic pruning) continues to occur in the cortex. As it occurs, we see a corresponding change in what the child is capable of doing. Remember that myelin is the coating around the axon that facilitates neural transmission. Synaptic pruning refers to the loss of synapses that are unused. As myelination and pruning increase during this stage of development, neural processes become quicker and more complex.

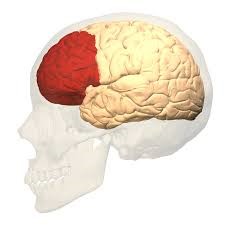

Greater development in the prefrontal cortex, the area of the brain behind the forehead that helps us to think, strategize, and control emotions, makes it increasingly possible to control emotional outbursts and to understand how to play games. Consider 4- or 5-year-old children and how they might approach a game of soccer. Chances are every move would be a response to the commands of a coach standing nearby calling out, “Run this way! Now, stop. Look at the ball. Kick the ball!” And when children are not being told what to do, they will likely be looking at the clover on the ground or a dog on the other side of the fence! Understanding the game, thinking ahead, and coordinating movement improves with practice and myelination. Demonstrating resilience and recovering from a loss, hopefully, does as well.

Growth in the hemispheres and corpus callosum

Between ages 3 and 6, the left hemisphere of the brain, which tends to lag behind in terms of activity during the first 3 years of life, increases in activity, which correlates with the burst in language skills during this time period. Activity in the right hemisphere grows steadily throughout early childhood and is especially involved in tasks that require spatial skills such as recognizing shapes and patterns. Both sides of the brain work together. There is no such thing as a person being either left-brained or right-brained. The corpus callosum, which connects the two hemispheres of the brain, undergoes a growth spurt between ages 3 and 6 as well resulting in improved coordination between right and left hemisphere tasks.

I once saw a 5-year-old hopping on one foot, rubbing his stomach and patting his head all at the same time. I asked him what he was doing and he replied, “My teacher said this would help my corpus callosum!” Apparently, his kindergarten teacher had explained the process!

Visual Pathways

Have you ever examined the drawings of young children? If you look closely, you can almost see the development of visual pathways reflected in the way these images change as pathways become more mature. Early scribbles and dots illustrate the use of simple motor skills. No real connection is made between an image being visualized and what is created on paper.

At age 3, the child begins to draw wispy creatures with heads and not much other detail. Gradually pictures begin to have more detail and incorporate more parts of the body. Arm buds become arms and faces take on noses, lips, and eventually eyelashes.

Motor Skill Development

Remember that gross motor skills are voluntary movements involving the use of large muscle groups while fine motor skills are more exact movements of the hands and fingers and include the ability to reach and grasp an object. Early childhood is a time of development of both gross and fine motor skills.

Early childhood is a time when children are especially attracted to motion and song. Days are filled with moving, jumping, running, swinging and clapping, and every place becomes a playground. Even the booth at a restaurant affords the opportunity to slide around in the seat or disappear underneath and imagine being a sea creature in a cave! Children may frequently ask their caregivers to “look at me”. Songs are often accompanied by arm and leg movements or cues to turn around or move from left to right. Running, jumping, dancing movements, etc. help to improve children’s gross motor skills.

Fine motor skills are also being refined in activities such as pouring water into a container, drawing, coloring, and using scissors. Some children’s songs promote fine motor skills as well (“itsy, bitsy, spider” song). Mastering the fine art of cutting one’s own fingernails or tying their shoes will take a lot of practice and maturation. Fine motor skills continue to develop through middle childhood.

|

Age |

Gross Motor Skills |

Fine Motor Skills |

|

Age 2 |

Can kick a ball without losing balance Can pick up objects while standing, without losing balance (This often occurs by 15 months. It is a cause for concern if not seen by 2 years.) Can run with better coordination. (May still have a wide stance.) |

Able to turn a doorknob Can look through a book turning one page at a time Can build a tower of six to seven cubes Able to put on simple clothes without help (The child is often better at removing clothes than putting them on) |

|

Age 3 |

Can briefly balance and hop on one foot May walk on stairs with alternating feet (without holding onto rail) Can pedal a tricycle |

Can build a block tower of more than nine cubes Can easily place small objects in a small opening Can copy a circle Drawing a person with 3 parts Feeds self easily |

|

Age 4 |

Shows improved balance Hops on one foot without losing balance Throws a ball overhead with coordination |

Can cut out a picture using scissors Drawing a square Managing a spoon and fork neatly while eating Putting on clothes properly |

|

Age 5 |

Has better coordination (getting the arms, legs, and body to work together) Skips, jumps and hops with good balance Stays balanced while standing on one foot with eyes closed |

Shows more skills with simple tools and writing utensils Can copy a triangle Can use a knife to spread soft foods |

Nutrition

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 1 in 5 American children between the ages of 2 and 5 are overweight or obese. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends a number of steps to help reduce the chances of obesity in young children. Removing high-calorie low-nutrition foods from the diet, offering whole fruits and vegetables instead of just juices, and getting kids active are just some of the recommendations that they make. Replacing sugar sweetened beverages with water helps to reduce the accumulation of body fat in school-aged children.[5] This increase in water consumption reduces the risk of obesity by 31%. Finally, the AAP suggests that parents can begin offering milk with a lower fat percentage (2%, 1%, or skim milk) to 2-year-olds. The switch to lower fat milk may help avoid some of the obesity issues discussed above. Parents should avoid giving the child too much milk as calcium interferes with the absorption of iron in the diet as well.

Caregivers need to keep in mind that they are influencing taste preferences at this age. Young children who grow accustomed to high-fat, very sweet, and salty flavors may have trouble eating foods that have more subtle flavors such as fruits and vegetables. Offering a diet of diverse food options, limiting foods with high calories but low nutritional value, and limiting high-calorie drink options can all contribute greatly to a child’s health and risk of obesity during this stage of life and future stages.

Caregivers who have established a feeding routine with a child can find the normal reduction in appetite a bit frustrating and become concerned that the child is going to starve. However, by providing adequate, sound nutrition, and limiting sugary snacks and drinks, the caregiver can be assured that the child will not starve, and the child will receive adequate nutrition. Well-balanced nutrition is vital in preventing iron deficiencies.

Consider the following advice about establishing eating patterns for years to come.[6] Notice that keeping mealtime pleasant, providing sound nutrition, and not engaging in power struggles over food are the main goals.

- 1Don’t try to force your child to eat or fight over food. Of course, it is impossible to force someone to eat. But the real advice here is to avoid turning food into some kind of ammunition during a fight. Do not teach your child to eat to or refuse to eat in order to gain favor or express anger toward someone else.

- Recognize that appetite varies. Children may eat well at one meal and have no appetite at another. Rather than seeing this as a problem, it may help to realize that appetites do vary. Continue to provide good nutrition, but do not worry excessively if the child does not eat.

- Keep it pleasant. This tip is designed to help caregivers create a positive atmosphere during mealtime. Mealtimes should not be the time for arguments or expressing tensions. You do not want the child to have painful memories of mealtimes together or have nervous stomachs and problems eating and digesting food due to stress.

- No short order chefs. While it is fine to prepare foods that children enjoy, preparing a different meal for each child or family member sets up an unrealistic expectation from others. Children probably do best when they are hungry and a meal is ready. Limiting snacks rather than allowing children to “graze” continuously can help create an appetite for whatever is being served.

- Limit choices. If you give your preschool-aged child choices, make sure that you give them one or two specific choices rather than asking “What would you like for lunch?” If given an open choice, children may change their minds or choose whatever their sibling does not choose!

- Serve balanced meals. This tip encourages caregivers to serve balanced meals. A box of macaroni and cheese is not a balanced meal. Meals prepared at home tend to have better nutritional value than fast food or frozen dinners. Prepared foods tend to be higher in fat and sugar content as these ingredients enhance taste and profit margin because fresh food is often more costly and less profitable. However, preparing fresh food at home is not as costly. But ot does require more activity and planning. Preparing meals and including the children in kitchen chores can provide fun and memorable experiences.

- Don’t bribe. Bribing a child to eat vegetables by promising dessert is not a good idea. For one reason, the child will likely find a way to get the dessert without eating the vegetables (by whining or fidgeting, perhaps, until the caregiver gives in), and for another reason, because it teaches the child that some foods are better than others. Children tend to naturally enjoy a variety of foods until they are taught that some are considered less desirable than others. A child, for example, may learn the broccoli they have enjoyed is seen as yucky by others unless it’s smothered in cheese sauce!

Sexual Health Development in Early Childhood

Historically, children have been thought of as innocent or incapable of sexual arousal.[7] A more modern approach to sexuality suggests that the physical dimension of sexual arousal is present from birth. That said, it seems to be the case that the elements of seduction, power, love, or lust that are part of the adult meanings of sexuality are not present in sexual arousal at this stage. In contrast, sexuality begins in childhood as a response to physical states and sensations and cannot be interpreted as similar to that of adults in any way.[8]

Infancy

Children are capable of erections and vaginal lubrication even before birth.[9] Arousal can signal overall physical contentment and stimulation that accompanies feeding or warmth. Infants begin to explore their bodies and touch their genitals as soon as they have sufficient motor skills. This stimulation is for comfort or to relieve tension rather than to reach orgasm.[10]

Early Childhood

Self-stimulation is common in early childhood for both boys and girls. Curiosity about the body and about others’ bodies is a natural part of early childhood as well. Consider this example. A mother is asked by her young daughter: “So it’s okay to see a boy’s privates as long as it’s the boy’s mother or a doctor?” The mother hesitates a bit and then responds, “Yes. I think that’s alright.” “Hmmm,” the girl begins, “When I grow up, I want to be a doctor!” Hopefully, this subject is approached in a way that teaches children to be safe and know what is appropriate without frightening them or causing shame.

As children grow, they are more likely to show their genitals to siblings or peers, and to take off their clothes and touch each other.[11] Masturbation is common among this age group.[12]

Hopefully, parents respond to this without undue alarm and without making the children feel guilty about their bodies. Instead, messages about what is going on and the appropriate time and place for such activities help the child learn.

Parents should take the time to speak with their children about when it is appropriate for other people to see or touch them. Many experts suggest that this should occur as early as age 3, and of course the discussion should be developmentally-appropriate for the child’s age and abilities. One way to help a young child understand inappropriate touching is to discuss “bathing suit areas.” Kids First, Inc. suggests discussing the following: “No one should touch you anywhere your bathing suit covers. No one should ask you to touch them somewhere that their bathing suit covers. No one should show you a part of their or someone else’s bodies that their bathing suit covers.” Further, instead of talking about good or bad touching, talk about safe and unsafe touching.[13]

- Van Rossem, R., & Pannecoucke, I. (2019). Poverty and a child’s height development during early childhood: A double disadvantage? A study of the 2006-2009 birth cohorts in Flanders. PloS One, 14(1), e0209170. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0209170 ↵

- Neumann, J. (September 2015). Small height differences among kids may reflect economic disparities. Reuters, Health News. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-children-height-poverty/small-height-differences-among-kids-may-reflect-economic-disparities-idUSKCN0RR11720150927. ↵

- Kerr, G. R., Lee, E. S., Lorimor, R. J., Mueller, W. H., & Lam, M. M. (1982). Height distributions of U.S. children: associations with race, poverty status and parental size. Growth, 46(2), 135–149. ↵

- Table adapted from NIH (2018) https://open.maricopa.edu/psy240mm/chapter/chapter-5-early-childhood/ ↵

- Franse, C. B., Wang, L., Constant, F., Fries, L. R., & Raat, H. (2019, August 13). Factors associated with water consumption among children: A systematic review - international journal of behavioral nutrition and physical activity. BioMed Central. Retrieved February 25, 2022, from https://ijbnpa.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12966-019-0827-0#citeas ↵

- Rice, F. P. (1997). Human development: A life-span approach. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. ↵

- Aries, P. (1987). Centuries of Childhood. Penguin Books. ↵

- Carroll, J. L. (2007). Sexuality now: Embracing diversity (2nd ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson. ↵

- Martinson, F. M. (1981). Eroticism in infancy and childhood. In L. L. Constantine & F. M. Martinson (Eds.), Children and sex: New findings, new perspectives. (pp. 23-35). Boston: Little, Brown. ↵

- Carroll, J. L. (2007). Sexuality now: Embracing diversity (2nd ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson. ↵

- Okami, P., Olmstead, R., & Abramson, P. R. (1997). Sexual experiences in early childhood: 18-year longitudinal data from UCLA Family Lifestyles Project. Journal of Sex Research, 34(4), 339-347. ↵

- Schwartz, I. M. (1999). Sexual activity prior to coitus initiation: A comparison between males and females. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 28(1), 63-69. ↵

- Kids First, Inc. (2022). How to Talk to Young Children About Body Safety. https://www.kidsfirstinc.org/how-to-talk-to-young-children-about-body-safety/. ↵