Psychosocial Development in Early Adulthood

Diana Lang; Nick Cone; Margaret Clark-Plaskie; Laura Overstreet; Martha Lally; and Suzanne Valentine-French

From a lifespan developmental perspective, growth and development do not stop in childhood or adolescence; they continue throughout adulthood. In this section we will build on Erikson’s psychosocial stages, then be introduced to theories about transitions that occur during adulthood. More recently, Arnett notes that transitions to adulthood happen at later ages than in the past and he proposes that there is a new stage between adolescence and early adulthood called, “emerging adulthood.”

Erikson’s Theory

Intimacy vs. Isolation

Erikson[1] believed that the main task of early adulthood is to establish intimate relationships and not feel isolated from others. Intimacy does not necessarily involve romance; it involves caring about another and sharing one’s self without losing one’s self. This developmental crisis of “intimacy versus isolation” is affected by how the adolescent crisis of “identity versus role confusion” was resolved (in addition to how the earlier developmental crises in infancy and childhood were resolved). The young adult might be afraid to get too close to someone else and lose her or his sense of self, or the young adult might define her or himself in terms of another person. Intimate relationships are more difficult if one is still struggling with identity. Achieving a sense of identity is a life-long process, but there are periods of identity crisis and stability. Additional, according to Erikson,[2] having some sense of identity is essential for intimate relationships. Although, consider what that would mean for previous generations of women who may have defined themselves through their husbands and marriages, or for Eastern cultures today that value interdependence rather than independence.

Friendships as a source of intimacy

In our twenties, intimacy needs may be met in friendships rather than with partners. This is especially true in the United States today as many young adults postpone making long-term commitments to partners either in marriage or in cohabitation.

Gaining Adult Status

Many of the developmental tasks of early adulthood involve becoming part of the adult world and gaining independence. Young adults sometimes complain that they are not treated with respect, especially if they are put in positions of authority over older workers. Consequently, young adults may emphasize their age to gain credibility from those who are even slightly younger. “You’re only 23? I’m 27!” a young adult might exclaim. [Note: This kind of statement is much less likely to come from someone in their 40s!]

The focus of early adulthood is often on the future. Many aspects of life are on hold while people seek additional education, go to work, and prepare for a brighter future. There may be a belief that the hurried life now lived will improve ‘as soon as I finish school’ or ‘as soon as I get promoted’ or ‘as soon as the children get a little older.’ As a result, time may seem to pass rather quickly. The day consists of meeting many demands that these tasks bring. The incentive for working so hard is that it will all result in a better future.

Adulthood, then, is a period of building and rebuilding one’s life. Many of the decisions that are made in early adulthood are made before a person has had enough experience to really understand the consequences of such decisions. And, perhaps, many of these initial decisions are made with one goal in mind – to be seen as an adult. As a result, early decisions may be driven more by the expectations of others. For example, imagine someone who chose a career path based on other’s advice but now finds that the job is not what was expected.

Temperament and Personality in Early Adulthood

Remember, temperament is defined as the innate characteristics of the infant, including mood, activity level, and emotional reactivity, noticeable soon after birth. Does one’s temperament remain stable through the lifespan? Do shy and inhibited babies grow up to be shy adults, while the sociable child continues to be the life of the party? Like most developmental research the answer is more complicated than a simple yes or no. Chess and Thomas,[3] who identified children as easy, difficult, slow-to-warm-up or blended, found that children identified as easy grew up to became well-adjusted adults, while those who exhibited a difficult temperament were not as well-adjusted as adults. Kagan[4] has studied the temperamental category of inhibition to the unfamiliar in children. Infants exposed to unfamiliarity reacted strongly to the stimuli and cried loudly, pumped their limbs, and had an increased heart rate. Research has indicated that these highly reactive children show temperamental stability into early childhood, and Bohlin and Hagekull[5] found that shyness in infancy was linked to social anxiety in adulthood.

An important aspect of this research on inhibition was looking at the response of the amygdala, which is important for fear and anxiety, especially when confronted with possible threatening events in the environment. Using functional magnetic resonance imaging (FMRIs) young adults identified as strongly inhibited toddlers showed heightened activation of the amygdala when compared to those identified as uninhibited toddlers.[6]

The research does seem to indicate that temperamental stability holds for many individuals through the lifespan, yet we know that one’s environment can also have a significant impact. Recall from our discussion on epigenesis or how environmental factors are thought to change gene expression by switching genes on and off. Many cultural and environmental factors can affect one’s temperament, including supportive versus abusive child-rearing, socioeconomic status, stable homes, illnesses, teratogens, etc. Additionally, individuals often choose environments that support their temperament, which in turn further strengthens them.[7] In summary, because temperament is genetically driven, genes appear to be the major reason why temperament remains stable into adulthood. In contrast, the environment appears mainly responsible for any change in temperament.[8]

Everybody has their own unique personality; that is, their characteristic manner of thinking, feeling, behaving, and relating to others.[9] Personality traits refer to these characteristic, routine ways of thinking, feeling, and relating to others. Personality integrates one’s temperament with cultural and environmental influences. Consequently, there are signs or indicators of these traits in childhood, but they become particularly evident when the person is an adult. Personality traits are integral to each person’s sense of self, as they involve what people value, how they think and feel about things, what they like to do, and, basically, what they are like most every day throughout much of their lives.

Five-Factor Model

There are hundreds of different personality traits, and all of these traits can be organized into the broad dimensions referred to as the Five-Factor Model.[10] These five broad domains include: Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism (Think OCEAN to remember). This applies to traits that you may use to describe yourself. Table 7.2 provides illustrative traits for low and high scores on the five domains of this model of personality.

|

Dimension |

Description |

Examples of behaviors predicted by the trait |

|

Openness to experience |

A general appreciation for art, emotion, adventure, unusual ideas, imagination, curiosity, and variety of experience |

Individuals who are highly open to experience tend to have distinctive and unconventional decorations in their home. They are also likely to have books on a wide variety of topics, a diverse music collection, and works of art on display. |

|

Conscientiousness |

A tendency to show self- discipline, act dutifully, and aim for achievement |

Individuals who are conscientious have a preference for planned rather than spontaneous behavior. |

|

Extraversion |

The tendency to experience positive emotions and to seek out stimulation and the company of others |

Extroverts enjoy being with people. In groups they like to talk, assert themselves, and draw attention to themselves. |

|

Agreeableness |

A tendency to be compassionate and cooperative rather than suspicious and antagonistic toward others; reflects individual differences in general concern for social harmony |

Agreeable individuals value getting along with others. They are generally considerate, friendly, generous, helpful, and willing to compromise their interests with those of others. |

|

Neuroticism |

The tendency to experience negative emotions, such as anger, anxiety, or depression; sometimes called “emotional instability” |

Those who score high in neuroticism are more likely to interpret ordinary situations as threatening and minor frustrations as hopelessly difficult. They may have trouble thinking clearly, making decisions, and coping effectively with stress. |

Personality can change throughout adulthood. Longitudinal studies reveal average changes during adulthood in the expression of some traits (e.g., neuroticism and openness decrease with age and conscientiousness increases) and individual differences in these patterns due to idiosyncratic life events (e.g., divorce, illness). Longitudinal research also suggests that adult personality traits, such as conscientiousness, predict important life outcomes including job success, health, and longevity.[12][13]

The Harvard Health Letter[14] identifies research correlations between conscientiousness and lower blood pressure, lower rates of diabetes and stroke, fewer joint problems, being less likely to engage in harmful behaviors, being more likely to stick to healthy behaviors, and more likely to avoid stressful situations. Conscientiousness also appears related to career choices, friendships, and stability of marriage. Lastly, a person possessing both self-control and organizational skills, both related to conscientiousness, may withstand the effects of aging better and have stronger cognitive skills than one who does not possess these qualities.

Attachment

Attachment in Emerging/Young Adulthood

|

Secure |

I find it relatively easy to get close to others and am comfortable depending on them and having them depend on me. I don’t often worry about being abandoned or about someone getting too close to me. |

|

Avoidant |

I am somewhat uncomfortable being close to others; I find it difficult to trust them completely, difficult to allow myself to depend on them. I am nervous when anyone gets too close, and often, love partners want me to be more intimate than I feel comfortable being. |

|

Anxious/Ambivalent |

I find that others are reluctant to get as close as I would like. I often worry that my partner doesn’t really love me or won’t stay with me. I want to merge completely with another person, and this sometimes scares people away. |

Hazan and Shaver[16] described the attachment styles of adults, using the same three general categories proposed by Ainsworth’s research on young children; secure, avoidant, and anxious/ambivalent. Hazan and Shaver developed three brief paragraphs describing the three adult attachment styles. Adults were then asked to think about romantic relationships they were in and select the paragraph that best described the way they felt, thought, and behaved in these relationships (See Table 7.3.).[17]

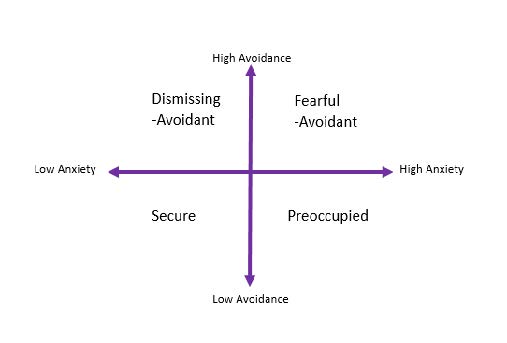

Bartholomew[18] challenged the categorical view of attachment in adults and suggested that adult attachment was best described as varying along two dimensions; attachment related-anxiety and attachment-related avoidance. Attachment-related anxiety refers to the extent to which an adult worries about whether their partner really loves them. Those who score high on this dimension fear that their partner will reject or abandon them.[19] Attachment-related avoidance refers to whether an adult can open up to others, and whether they trust and feel they can depend on others. Those who score high on attachment- related avoidance are uncomfortable with opening up and may fear that such dependency may limit their sense of autonomy.[20] According to Bartholomew[21] this would yield four possible attachment styles in adults; secure, dismissing, preoccupied, and fearful- avoidant (see Figure 7.10)

Securely attached adults score lower on both dimensions. They are comfortable trusting their partners and do not worry excessively about their partner’s love for them. Adults with a dismissing style score low on attachment-related anxiety, but higher on attachment-related avoidance. Such adults dismiss the importance of relationships. They trust themselves, but do not trust others, thus do not share their dreams, goals, and fears with others. They do not depend on other people, and feel uncomfortable when they have to do so.

Those with a preoccupied attachment are low in attachment-related avoidance, but high in attachment-related anxiety. Such adults are often prone to jealousy and worry that their partner does not love them as much as they need to be loved. Adults whose attachment style is fearful- avoidant score high on both attachment-related avoidance and attachment-related anxiety. These adults want close relationships, but do not feel comfortable getting emotionally close to others. They have trust issues with others and often do not trust their own social skills in maintaining relationships.

Research on attachment in adulthood has found that:

Adults with insecure attachments report lower satisfaction in their relationships.[22][23]

Those high in attachment-related anxiety tend to report more daily conflict in their relationships.[24]

Those with avoidant attachment exhibit less support to their partners.[25]

Young adults tend to show greater attachment-related anxiety than do middle-aged or older adults.[26]

Some studies report that young adults tend to show more attachment-related avoidance,[27] while other studies find that middle-aged adults tend to show higher avoidance than younger or older adults.[28]

Young adults with more secure and positive relationships with their parents tend to make the transition to adulthood more easily than do those with more insecure attachments.[29]

Do people with certain attachment styles attract those with similar styles?

When people are asked what kinds of psychological or behavioral qualities they are seeking in a romantic partner, a large majority of people indicate that they are seeking someone who is kind, caring, trustworthy, and understanding, that is the kinds of attributes that characterize a “secure” caregiver.[30] However, we know that people do not always end up with others who meet their ideals. Are secure people more likely to end up with secure partners, and, vice versa, are insecure people more likely to end up with insecure partners? The majority of the research that has been conducted to date suggests that the answer is “yes.”

One important question is whether these findings exist because (a) secure people are more likely to be attracted to other secure people, (b) secure people are likely to create security in their partners over time, or (c) some combination of these possibilities. Existing empirical research strongly supports the first alternative. For example, when people have the opportunity to interact with individuals who vary in security in a speed-dating context, they express a greater interest in those who are higher in security than those who are more insecure.[31] However, there is also some evidence that people’s attachment styles mutually shape one another in close relationships.

Childhood experiences shape adult attachment

The majority of research on this issue relies on adults’ reports of what they recall about their childhood experiences. This kind of work suggests that secure adults are more likely to describe their early childhood experiences with their parents as being supportive, loving, and kind.[32] A number of longitudinal studies are emerging that demonstrate prospective associations between early attachment experiences and adult attachment styles and/or interpersonal functioning in adulthood.

It is easy to come away from such findings with the mistaken assumption that early experiences “determine” later outcomes. To be clear: Attachment theorists assume that the relationship between early experiences and subsequent outcomes is probabilistic, not deterministic. Having supportive and responsive experiences with caregivers early in life is assumed to set the stage for positive social development. But that does not mean that attachment patterns cannot change over time. For instance, even if an individual has far from optimal experiences in early life, attachment theory suggests that it is possible for that individual to develop well-functioning adult relationships through a number of corrective experiences, including relationships with siblings, other family members, teachers, and close friends. Security is best viewed as a culmination of a person’s attachment history rather than a reflection of only the person’s early experiences. Those early experiences are considered important, not because they determine a person’s fate, but because they provide the foundation for subsequent experiences.

- Erikson, E. H. (1950). Childhood and society. W W Norton & Co. ↵

- Erikson, E. H. (1950). Childhood and society. W W Norton & Co. ↵

- Chess, S., & Thomas, A. (1984). Origins and evolution of behavior disorders: From infancy to early adult life. Harvard University Press. ↵

- Kagan, J. (2003). Behavioral inhibition as a temperamental category. In R. J. Davidson, K. R. Scherer, & H. H. Goldsmith (Eds.), Handbook of affective sciences (pp. 320–331). Oxford University Press. ↵

- Bohlin, G., & Hagekull, B. (2009). Socio-emotional development: from infancy to young adulthood. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 50(6), 592–601. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9450.2009.00787.x ↵

- Davidson, R., & Begley, S. (2013). The emotional life of your brain: How its unique patterns affect the way you think, feel, and live - and how you can change them. Hodder Paperback. ↵

- Cain, S. (2012). Quiet. New York: Crown Publishing Group. ↵

- Clark, L. A., & Watson, D. (1999). Temperament: A new paradigm for trait psychology. In L. A. Pervin & O. P. John (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (pp. 399–423). Guilford Press. ↵

- John, O. P., Naumann, L. P., & Soto, C. J. (2008). Paradigm shift to the integrative Big Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and conceptual issues. In O. P. John, R. W. Robins, & L. A. Pervin (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (pp. 114–158). The Guilford Press. ↵

- John, O. P., Naumann, L. P., & Soto, C. J. (2008). Paradigm shift to the integrative Big Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and conceptual issues. In O. P. John, R. W. Robins, & L. A. Pervin (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (pp. 114–158). The Guilford Press. ↵

- John, O. P., Naumann, L. P., & Soto, C. J. (2008). Paradigm shift to the integrative Big Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and conceptual issues. In O. P. John, R. R. Robins, & L. A. Pervin (Eds.), Handbook of personality. Theory and research (3rd ed., pp. 114–158). New York, NY: Guilford Press. ↵

- Friedman, H. S., Tucker, J. S., Tomlinson-Keasey, C., Schwartz, J. E., Wingard, D. L., & Criqui, M. H. (1993). Does childhood personality predict longevity? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65(1), 176–185. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.65.1.176 ↵

- Roberts, B. W., Kuncel, N. R., Shiner, R., Caspi, A., & Goldberg, L. R. (2007). The power of personality: The comparative validity of personality traits, socioeconomic status, and cognitive ability for predicting important life outcomes. Perspectives on Psychological Science: A Journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 2(4), 313–345. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6916.2007.00047.x ↵

- Harvard Health Letter. (2012). Raising your conscientiousness. http://www.helath.harvard.edu ↵

- Hazan, C., & Shaver, P. (1987). Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 511-524. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.52.3.511 ↵

- Hazan, C., & Shaver, P. (1987). Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 511-524. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.52.3.511 Page 515 ↵

- This section was adapted from Lumen Learning's Lifespan Development, adapted from content authored by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French, available under a Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License ↵

- Bartholomew, K. (1990). Avoidance of intimacy: An attachment perspective. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 7(2), 147–178. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407590072001 ↵

- Fraley, R. C., Hudson, N. W., Heffernan, M. E., & Segal, N. (2015). Are adult attachment styles categorical or dimensional? A taxometric analysis of general and relationship-specific attachment orientations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109(2), 354–368. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000027 ↵

- Fraley, R. C., Hudson, N. W., Heffernan, M. E., & Segal, N. (2015). Are adult attachment styles categorical or dimensional? A taxometric analysis of general and relationship-specific attachment orientations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109(2), 354–368. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000027 ↵

- Bartholomew, K. (1990). Avoidance of intimacy: An attachment perspective. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 7(2), 147–178. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407590072001 ↵

- Butzer, B., & Campbell, L. (2008). Adult attachment, sexual satisfaction, and relationship satisfaction: A study of married couples. Personal Relationships, 15(1), 141–154. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.2007.00189.x ↵

- Holland, A. S., Fraley, R. C., & Roisman, G. I. (2012). Attachment styles in dating couples: Predicting relationship functioning over time. Personal Relationships, 19(2), 234–246. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.2011.01350.x ↵

- Campbell, L., Simpson, J. A., Boldry, J., & Kashy, D. A. (2005). Perceptions of conflict and support in romantic relationships: the role of attachment anxiety. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88(3), 510–531. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.88.3.510 ↵

- Simpson, J. A., Rholes, W. S., Oriña, M. M., & Grich, J. (2002). Working models of attachment, support giving, and support seeking in a stressful situation. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 28(5), 598–608. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167202288004 ↵

- Chopik, W. J., Edelstein, R. S., & Fraley, R. C. (2013). From the cradle to the grave: age differences in attachment from early adulthood to old age: Attachment from early to older adulthood. Journal of Personality, 81(2), 171–183. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2012.00793.x ↵

- Schindler, I., Fagundes, C. P., & Murdock, K. W. (2010). Predictors of romantic relationship formation: Attachment style, prior relationships, and dating goals. Personal Relationships, 17(1), 97–105. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.2010.01255.x ↵

- Chopik, W. J., Edelstein, R. S., & Fraley, R. C. (2013). From the cradle to the grave: age differences in attachment from early adulthood to old age: Attachment from early to older adulthood. Journal of Personality, 81(2), 171–183. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2012.00793.x ↵

- Fraley, R. C. (2013). Attachment through the life course. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF publishers. nobaproject.com. ↵

- Chappell, K. D., & Davis, K. E. (1998). Attachment, partner choice, and perception of romantic partners: An experimental test of the attachment-security hypothesis. Personal Relationships, 5(3), 327–342. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.1998.tb00175.x ↵

- McClure, M. J., Lydon, J. E., Baccus, J. R., & Baldwin, M. W. (2010). A signal detection analysis of chronic attachment anxiety at speed dating: being unpopular is only the first part of the problem. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 36(8), 1024–1036. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167210374238 ↵

- Hazan, C., & Shaver, P. (1987). Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(3), 511–524. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.52.3.511 ↵