Relationships in Early Adulthood

Diana Lang; Nick Cone; Margaret Clark-Plaskie; Martha Lally; Suzanne Valentine-French; Laura Overstreet; Lumen Learning; Wikimedia Contributors; Sarah Hoiland; and Julie Lazzara

We have learned from Erikson that the psychosocial developmental task of early adulthood is “intimacy versus isolation” and if resolved relatively positively, it can lead to the virtue of “love.” In this section, we will look more closely at relationships in early adulthood, particularly in terms of love, dating, cohabitation, marriage, and parenting.

Relationships with Parents, Caregivers, and Siblings

In early adulthood the parent-child relationship should transition toward a relationship between two adults. This involves a reappraisal of the relationship by both parents and young adults.

For some parents/caregivers, especially during emerging adulthood, it is difficult for them to interact with their adult children as “adults.” Aquilino[1] suggests that parents who are reluctant or unable to do so may hinder young adults’ identity development. Arnett[2] reported that leaving home often helped promote psychological growth and independence in early adulthood.

Sibling relationships are one of the longest-lasting bonds in people’s lives. Yet, there is little research on the nature of sibling relationships in adulthood.[3] What is known is that the nature of these relationships change, as adults have a choice as to whether they will maintain a close bond and continue to be a part of the life of a sibling. Siblings must make the same reappraisal of each other as adults, as parents have to with their adult children. Research has shown a decline in the frequency of interactions between siblings during early adulthood, as presumably peers, romantic relationships, and children become more central to the lives of young adults. Aquilino[4] suggests that the task in early adulthood may be to maintain enough of a bond so that there will be a foundation for this relationship in later life. Those who are successful can often move away from the “older-younger” sibling conflicts of childhood, toward a more equal relationship between two adults. Siblings that were close to each other in childhood are typically close in adulthood.[5][6]

Attraction and Love

Attraction

Why do some people hit it off immediately? Using scientific methods, psychologists have investigated factors influencing attraction and have identified a number of variables, such as similarity, proximity (physical or functional), familiarity, and reciprocity, that influence with whom we develop relationships.

Proximity

Often we “stumble upon” friends or romantic partners; this happens partly due to how close in proximity we are to those people. Specifically, proximity or physical nearness has been found to be one of the most significant factors in the development of relationships. For example, when young adults move out of their family-of-origin household, they tend to make friends consisting of classmates, roommates, and teammates (i.e., people close in proximity). Proximity allows people the opportunity to get to know one other and discover their similarities—all of which can result in a friendship or intimate relationship. Proximity is not just about geographic distance, but rather functional distance, or the frequency with which we cross paths with others. For example, young adults living outside of their family-of-origin’s household are more likely to become closer and develop relationships with people who live in the same building because they see them (i.e., cross paths) more often than they see people on a different floor. How does the notion of proximity apply in terms of online relationships? Levine[7] argues that in terms of developing online relationships and attraction, functional distance refers to being at the same place at the same time in a virtual world (i.e., a chat room or Internet forum)—crossing virtual paths.

Familiarity

One of the reasons why proximity matters to attraction is that it breeds familiarity; people are more attracted to that which is familiar. Just being around someone or being repeatedly exposed to them increases the likelihood that we will be attracted to them. We also tend to feel safe with familiar people, as it is likely we know what to expect from them. Dr. Zajonc[8] labeled this phenomenon the mere-exposure effect. More specifically, he argued that the more often we are exposed to a stimulus (e.g., sound, person) the more likely we are to view that stimulus positively.

There is a certain comfort in knowing what to expect from others; consequently, research suggests that we like what is familiar. While this is often on a subconscious level, research has found this to be one of the most basic principles of attraction.[9] For example, young people who are reared by an overbearing primary caregiver may be attracted to other overbearing individuals not because they like being dominated but rather because it is what they consider to be normal (i.e., familiar).

Similarity

While many make the argument that opposites attract, research has found that is generally not true; similarity is key; overall we tend to like others who are like us.

When it comes to marriage, research has found that couples tend to be very similar, particularly when it comes to age, social class, race, education, physical attractiveness, values, and attitudes.[10][11] This phenomenon is known as the matching hypothesis.[12][13] We like others who validate our points of view and who are similar in thoughts, desires, and attitudes.

Reciprocity

Another key component in attraction is reciprocity; this principle is based on the notion that we are more likely to like someone if they feel the same way toward us. In other words, it is hard to be friends with someone who is not friendly in return. Another way to think of it is that relationships are built on give and take; if one side is not reciprocating, then the relationship is doomed. Basically, we feel obliged to give what we get and to maintain equity in relationships. Researchers have found that this is true across cultures.[14]

Love

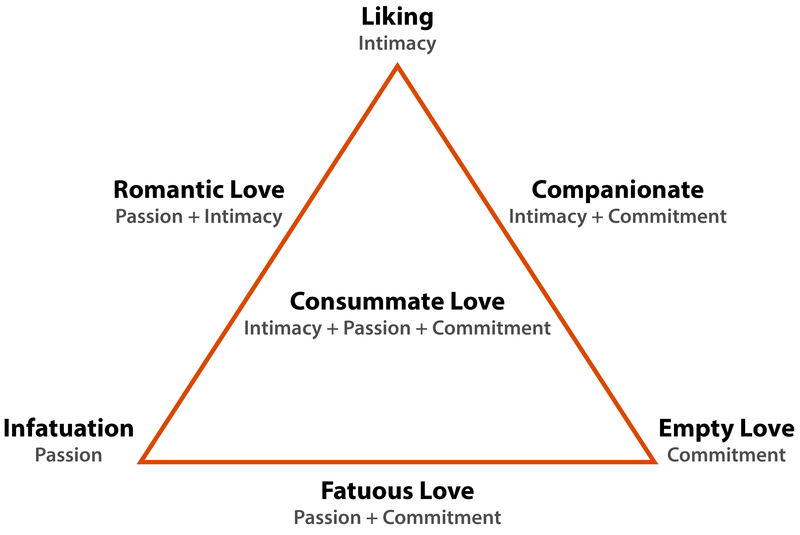

Is all love the same? Are there different types of love? Examining these questions more closely, Sternberg’s[15][16] work has focused on the notion that all types of love are comprised of three distinct areas: intimacy, passion, and commitment. Intimacy includes caring, closeness, and emotional support. The passion component of love is comprised of physiological and emotional arousal; these can include physical attraction, emotional responses that promote physiological changes, and sexual arousal. Lastly, commitment refers to the cognitive process and decision to commit to love another person and the willingness to work to keep that love over the course of your life. The elements involved in intimacy (caring, closeness, and emotional support) are generally found in all types of close relationships—for example, a mother’s love for a child or the love that friends share. Interestingly, this is not true for passion. Passion is unique to romantic love, differentiating friends from lovers. In sum, depending on the type of love and the stage of the relationship (i.e., newly in love), different combinations of these elements are present.

Taking this theory a step further, anthropologist Helen Fisher explained that she scanned the brains (using fMRI) of people who had just fallen in love and observed that their brain chemistry was “going crazy,” similar to the brain of an addict on a drug high.[17] Specifically, serotonin production increased by as much as 40% in newly-in-love individuals. Further, those newly in love tended to show obsessive-compulsive tendencies. Conversely, when a person experiences a breakup, the brain processes it in a similar way to quitting a heroin habit.[18] Thus, those who believe that breakups are physically painful are correct! Another interesting point is that long-term love and sexual desire activate different areas of the brain. More specifically, sexual needs activate the part of the brain that is particularly sensitive to innately pleasurable things such as food, sex, and drugs (i.e., the striatum—a rather simplistic reward system), whereas love requires conditioning—it is more like a habit. When sexual needs are rewarded consistently, then love can develop. In other words, love grows out of positive rewards, expectancies, and habit.[19]

Dive deeper into Helen Fisher’s research by watching her TED talk “The Brain in Love.”

Attachment Theory in Adulthood

The need for intimacy, or close relationships with others, is universal and persistent across the lifespan. What our adult intimate relationships look like actually stems from infancy and our relationship with our primary caregiver (historically our mother)—a process of development described by attachment theory, which you learned about in the module on infancy. Recall that according to attachment theory, different styles of caregiving result in different relationship “attachments.”

For example, responsive mothers—mothers who soothe their crying infants—tend to produce infants who have secure attachments.[20][21] As adults, secure individuals rely on their working models—concepts of how relationships operate—that were created in infancy, as a result of their interactions with their primary caregiver (mother), to foster happy and healthy adult intimate relationships. Securely attached adults feel comfortable being depended on and depending on others.

As you might imagine, inconsistent or dismissive parents also impact the attachment style of their infants,[22] but in a different direction. In early studies on attachment style, infants were observed interacting with their caregivers, followed by being separated from them, then finally reunited. About 20% of the observed children were “resistant,” meaning they were anxious even before, and especially during, the separation; and 20% were “avoidant,” meaning they actively avoided their caregiver after separation (i.e., ignoring the mother when they were reunited). These early attachment patterns can affect the way people relate to one another in adulthood. Anxious-resistant adults worry that others don’t love them, and they often become frustrated or angry when their needs go unmet. Anxious-avoidant adults will appear not to care much about their intimate relationships and are uncomfortable being depended on or depending on others themselves.

|

Secure Attachment |

Anxious-avoidant Attachment |

Anxious-resistant Attachment |

|

“I find it relatively easy to get close to others and am comfortable depending on them and having them depend on me. I don’t often worry about being abandoned or about someone getting too close to me,” |

“I am somewhat uncomfortable being close to others; I find it difficult to trust them completely, difficult to allow myself to depend on them. I am nervous when anyone gets too close, and often, love partners want me to be more intimate than I feel comfortable being.” |

“I find that others are reluctant to get as close as I would like. I often worry that my partner doesn’t really love me or won’t want to stay with me. I want to merge completely with another person, and this desire sometimes scares people away.” |

The good news is that our attachment can be changed. It isn’t easy, but it is possible for anyone to “recover” a secure attachment. The process often requires the help of a supportive and dependable other, and for the insecure person to achieve coherence—the realization that his or her upbringing is not a permanent reflection of character or a reflection of the world at large, nor does it bar him or her from being worthy of love or others of being trustworthy.[23]

Trends in Dating, Cohabitation, and Marriage

Singlehood

In the United States, being single is the most common lifestyle for people in their early 20s and there has been an increase in the number of adults staying single. In 1960, only about 1 in 10 adults age 25 or older had never been married, in 2012 that had risen to 1 in 5.[24] The number of adults who remain single across the world has also increased dramatically in the last 30 years. Singlehood has become a more acceptable lifestyle than it was in the past and many singles are very happy with their status. Whether or not a single person is happy depends on the circumstances of their remaining single.

Reasons for Staying Single

There are many reasons young adults cite for staying single, such as not having met the right person, wanting more financial stability, not ready to settle down, and feeling too young to marry.[25] In addition, adults are marrying later in life, cohabitating, and raising children outside of wedlock in greater numbers than in previous generations. Young adults also have other priorities, such as education, and establishing their careers. This may be reflected by changes in attitudes about the importance of marriage.

Dating

In general, traditional dating among teens and those in their early twenties has been replaced with more varied and flexible ways of getting together (technology with social media play a key role).

Dating and the Internet

The ways people are finding relationships has changed drastically with the advent of the Internet. As Finkel and colleagues[26] found, social networking sites, and the Internet generally, perform three important tasks. Specifically, sites provide individuals with access to a database of other individuals who are interested in meeting someone. Dating sites generally reduce issues of proximity, as individuals do not have to be close in proximity to meet. Also, they provide a medium in which individuals can communicate with others. Finally, some Internet dating websites advertise special matching strategies, based on factors such as personality, hobbies, and interests, to identify the “perfect match” for people looking for love online. In general, scientific questions about the effectiveness of Internet matching or online dating compared to face-to-face dating remain to be answered.

It is important to note that social networking sites have also opened the doors for many to meet people that they might not have ever had the opportunity to meet; unfortunately, it now appears that the social networking sites can be forums for unsuspecting people to be duped. In 2010 a documentary, Catfish,[27] focused on the personal experience of a man who met a woman online and carried on an emotional relationship with this person for months. As he later came to discover, though, the person he thought he was talking and writing with did not exist. Individuals should research people’s backgrounds and be cautious when meeting others from online sources.

Online communication differs from face-to-face interaction in a number of ways. In face-to-face meetings, people have many cues upon which to base their first impressions. A person’s looks, voice, mannerisms, dress, scent, and surroundings all provide information in face-to-face meetings, but in computer-mediated meetings, written messages are the only cues provided. Fantasy is used to conjure up images of voice, physical appearance, mannerisms, and so forth. The anonymity of online involvement may make it easier to become intimate without fear of interdependence. When online, people tend to disclose more intimate details about themselves more quickly. A shy person may open up more without worrying about whether or not the partner is frowning or looking away. And, someone who has been abused may feel safer in virtual relationships.

Hooking Up

United States demographic changes have significantly affected the romantic relationships among emerging and early adults. As previously described, the age for puberty has declined, while the times for one’s first marriage and first child have increased. This results in a “historically unprecedented time gap where young adults are physiologically able to reproduce, but not psychologically or socially ready to settle down and begin a family and child rearing.”[28] Consequently, traditional forms of dating have shifted for some people to include more casual hookups that involve uncommitted sexual encounters.[29][30]

Emotional Consequences of Hooking up

Concerns regarding hooking up behavior are evident in the research literature. One significant finding is the high comorbidity of hooking up and substance use. Those engaging in non-monogamous sex are more likely to have used marijuana, cocaine, and alcohol, and the overall risks of sexual activity are drastically increased with the addition of alcohol and drugs.[31] Regret has also been expressed, and those who had the most regret after hooking up also had more symptoms of depression.[32] Hook ups were also found associated with lower self-esteem, increase guilt, and foster feelings of using someone or feeling used.

Hooking up can best be explained by a biological, psychological, and social perspective. Research indicates that some emerging adults feel it is necessary to engage in hooking up behavior as part of the sexual script depicted in the culture and media. Additionally, they desire sexual gratification. However, many also want a more committed romantic relationship and may feel regret with uncommitted sex.

Friends with Benefits

Hookups are different than those relationships that involve continued mutual exchange. These relationships are often referred to as Friends with Benefits (FWB) or “Booty Calls.” These relationships involve friends having casual sex without commitment. Hookups do not include a friendship relationship. Bisson and Levine[33] found that 60% of 125 undergraduates reported a FWB relationship. The concern with FWB is that one partner may feel more romantically invested than the other.[34]

Cohabitation

Cohabitation is an arrangement where two or more people who are not married live together. These often involve a romantic or sexually intimate relationship on a more long-term or permanent basis. Such arrangements have become increasingly common in Western countries during the past few decades due to changing social views regarding marriage, gender roles, employment, and religion and economic changes. With many jobs now requiring advanced educational attainment, a competition between marriage and pursuing post-secondary education has ensued.[35]

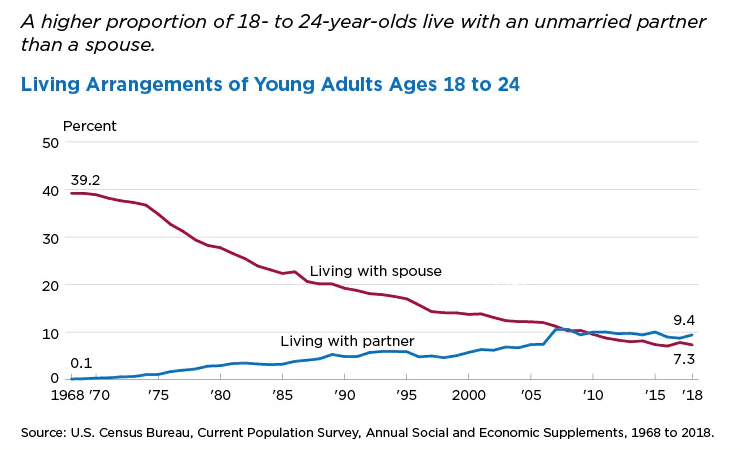

According to the U.S. Census Bureau,[36] cohabitation has been increasing, while marriage has been decreasing in young adulthood. As seen in the graph below, over the past 50 years, the percentage of 18-24 year olds in the U.S. living with an unmarried partner has gone from 0.1 percent to 9.4 percent, while living with a spouse has gone from 39.2 percent to 7 percent. More 18-24 year olds live with an unmarried partner now than with a married partner.

Similar increases in cohabitation have also occurred in other industrialized countries. For example, rates are high in Great Britain, Australia, Sweden, Denmark, and Finland. In fact, more children in Sweden are born to cohabiting couples than to married couples. In Europe, the Scandinavian countries have been the first to start this leading trend, although many countries have since followed. Mediterranean Europe has traditionally been very conservative, with religion playing a strong role.

Engagement and Marriage

Marriage Worldwide: Cohen[37] reviewed data assessing most of the world’s countries and found that marriage has declined universally during the last several decades. This decline has occurred in both poor and rich countries, however, the countries with the biggest drops in marriage were mostly rich: France, Italy, Germany, Japan and the U.S. Cohen states that the decline is not only due to individuals delaying marriage, but also because of high rates of non-marital cohabitation. Delayed or reduced marriage is associated with higher income and lower fertility rates that are reflected worldwide.

Marriage in the United States: In 1960, 72% of adults age 18 or older were married, in 2010 this had dropped to barely half.[38] At the same time, the age of first marriage has been increasing for both men and women. In 1960, the average age for first marriage was 20 for women and 23 for men. By 2010, this had increased to 26.5 for women and nearly 29 for men. Many of the explanations for increases in singlehood and cohabitation previously given can also account for the drop and delay in marriage.

Marriage and Elopement: Historically, marriage was not a personal choice, but one made by one’s family. Arranged marriages often ensured proper transference of a family’s wealth and the support of ethnic and religious customs. Such marriages were a marriage of families rather than of individuals. In Western Europe, starting in the 18th century the notion of personal choice in a marital partner slowly became the norm. Arranged marriages were seen as “traditional” and marriages based on love “modern”. Many of these early “love” marriages were obtained by eloping.[39]

In a majority of countries worldwide, most people will marry in their lifetime. Around the world, people tend to get married later in life or not at all. People in more developed countries (e.g., Nordic and Western Europe), for instance, typically marry later in life—at an average age of 30 years. This is very different than, for example, the economically developing country of Afghanistan, which has one of the lowest average-age statistics for marriage.[40]

Cultural Influences on Marriage

Many cultures have both explicit and unstated rules that specify who is an appropriate mate. Consequently, mate selection is not completely left to the individual. Rules of endogamy indicate the groups we should marry within and those we should not marry in.[41] For example, many cultures specify that people marry within their own race, social class, age group, or religion. Endogamy reinforces the cohesiveness of the group. Additionally, these rules encourage homogamy or marriage between people who share social characteristics. The majority of marriages in the U. S. are homogamous with respect to race, social class, age and to a lesser extent, religion. Homogamy is also seen in couples with similar personalities and interests.

Arranged Marriages

In some cultures, however, it is not uncommon for the families of young people to find a mate for them. In India, the marriage market refers to the use of marriage brokers or marriage bureaus to pair eligible singles together.[42] To many Westerners, the idea of arranged marriage can appear to take the romance out of the equation and violate values about personal freedom. On the other hand, some argue that parents are able to make more mature decisions than young people.

While such intrusions may seem inappropriate based on your upbringing, for many people of the world such help is expected, even appreciated. In India for example, “parental arranged marriages are largely preferred to other forms of marital choices.”[43] Of course, one’s religious and social caste plays a role in determining how involved family may be.

Same-Sex Marriage and Couples Worldwide

As of 2022, same-sex marriage is legal in 30 countries, and counting. Many other countries either recognize same-sex couples for the purpose of immigration, grant rights for domestic partnerships, or grant common law marriage status to same-sex couples. In June 26, 2015, the United States Supreme Court ruled that the Constitution guarantees same-sex marriage. The decision indicated that limiting marriage to only heterosexual couples violated the 14th amendment’s guarantee of equal protection under the law. This ruling occurred 11 years after same-sex marriage was first made legal in Massachusetts, and at the time of the high court decision, 36 states and the District of Columbia had legalized same sex marriage.[44]

Predictors of Marital Harmony

Advice on how to improve one’s marriage is centuries old. One expert on marital communication is John Gottman. Gottman[45] differs from many marriage counselors in his belief that having a good marriage does not depend on compatibility. Rather, the way that partners communicate to one another is crucial.

Gottman’s research team measured the physiological responses of thousands of couples as they discuss issues of disagreement. Fidgeting in one’s chair, leaning closer to or further away from the partner while speaking, and increases in respiration and heart rate are all recorded and analyzed along with videotaped recordings of the partners’ exchanges. In marriages destined to fail, partners engage in the “marriage killers”: Contempt, criticism, defensiveness, and stonewalling. Each of these undermines the caring and respect that healthy marriages require. To some extent, all partnerships include some of these behaviors occasionally, but when these behaviors become the norm, they can signal that the end of the relationships is near; for that reason, they are known as “Gottman’s Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse”. Contempt, which it entails mocking or derision and communicates the other partner is inferior, is seen of the worst of the four because it is the strongest predictor of divorce.

Gottman et al.[46] researched the perceptions newlyweds had about their partner and marriage via the Oral History Interview. This Interview analyzes eight variables in marriage including: Fondness/affection, we-ness, expansiveness/ expressiveness, negativity, disappointment, and three aspects of conflict resolution (chaos, volatility, glorifying the struggle), was able to predict the stability of the marriage (vs. divorce) with 87% accuracy at the four to six year-point and 81% accuracy at the seven to nine year-point. Later, Gottman[47] developed workshops for couples to strengthen their marriages based on the results of the Oral History Interview. Interventions include increasing positive regard for each other, strengthening their friendship, and improving communication and conflict resolution patterns.

Accumulated Positive Deposits to the “Emotional Bank Account.” When there is a positive balance of relationship deposits this can help the overall relationship in times of conflict. For instance, some research shows that being friendly and making deposits can change the nature of conflict. Gottman and Levenson[48] also found that couples rated as having more pleasant interactions, compared with couples with less pleasant interactions, reported higher marital satisfaction, less severe marital problems, better physical health, and less risk for divorce. Finally, Janicki et al.[49] showed that the intensity of conflict with a spouse predicted marital satisfaction, unless there was a record of positive partner interactions, in which case the conflict did not matter as much. Again, it seems as though having a positive balance through prior positive deposits helps to keep relationships strong even in the midst of conflict.

While Gottman’s research has contributed to our understandings of how to make marriages work, more current research demonstrates that these findings most likely extend to other types of romantic, committed relationships.

Additional techniques for maintaining or creating healthy relationships can be found on The Gottman Method website

- Aquilino, W. S. (2006). Family Relationships and Support Systems in Emerging Adulthood. In J. J. Arnett & J. L. Tanner (Eds.), Emerging adults in America: Coming of age in the 21st century (pp. 193–217). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/11381-008 ↵

- Arnett, J. J. (2003). Conceptions of the transition to adulthood among emerging adults in American ethnic groups. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2003(100), 63–75. https://doi.org/10.1002/cd.75 ↵

- Aquilino, W. S. (2006). Family Relationships and Support Systems in Emerging Adulthood. In J. J. Arnett & J. L. Tanner (Eds.), Emerging adults in America: Coming of age in the 21st century (pp. 193–217). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/11381-008 ↵

- Aquilino, W. S. (2006). Family Relationships and Support Systems in Emerging Adulthood. In J. J. Arnett & J. L. Tanner (Eds.), Emerging adults in America: Coming of age in the 21st century (pp. 193–217). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/11381-008 ↵

- Dunn, J. (1984). Sibling studies and the developmental impact of critical incidents. In P.B. Baltes & O.G. Brim (Eds.), Life-span development and behavior (Vol 6). Orlando, FL: Academic Press. ↵

- Dunn, J. (2007). Siblings and socialization. In J. E. Grusec & P. D. Hastings (Eds.), Handbook of socialization. New York: Guilford. ↵

- Levine, D. (2000). Virtual attraction: What rocks your boat. Cyberpsychology & Behavior: The Impact of the Internet, Multimedia and Virtual Reality on Behavior and Society, 3(4), 565–573. https://doi.org/10.1089/109493100420179 ↵

- Zajonc, R. B. (1968). Attitudinal effects of mere exposure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 9(2, Pt.2), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0025848 ↵

- Zajonc, R. B. (1980). Feeling and thinking: Preferences need no inferences. The American Psychologist, 35(2), 151–175. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.35.2.151 ↵

- McCann, V. (2016). Human relations: The art and science of building effective relationships, books a la carte (2nd ed.). Pearson. ↵

- Taylor, L. S., Fiore, A. T., Mendelsohn, G. A., & Cheshire, C. (2011). “Out of my league”: a real-world test of the matching hypothesis. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 37(7), 942–954. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167211409947 ↵

- Feingold, A. (1988). Matching for attractiveness in romantic partners and same-sex friends: A meta-analysis and theoretical critique. Psychological Bulletin, 104(2), 226–235. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.104.2.226 ↵

- Mckillip, J., & Redel, S. L. (1983). External validity of matching on physical attractiveness for same and opposite sex Couples1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 13(4), 328–337. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1983.tb01743.x ↵

- Gouldner, A. W. (1960). The norm of reciprocity: A preliminary statement. American Sociological Review, 25(2), 161. https://doi.org/10.2307/2092623 ↵

- Sternberg, R. J. (2004). A Triangular Theory of Love. In H. T. Reis & C. E. Rusbult (Eds.), Close relationships: Key readings (pp. 213–227). Taylor & Francis. ↵

- Sternberg, R. J. (2007). Triangulating Love. In Oord, T. J. The Altruism Reader: Selections from Writings on Love, Religion, and Science (pp 331-347). West Conshohocken, PA: Templeton Foundation. ↵

- Cohen, E. (2007, February 15). Loving with all your … brain. http://www.cnn.com/2007/HEALTH/02/14/love.science/. ↵

- Fisher, H. E., Brown, L. L., Aron, A., Strong, G., & Mashek, D. (2010). Reward, addiction, and emotion regulation systems associated with rejection in love. Journal of Neurophysiology, 104(1), 51–60. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.00784.2009 ↵

- Cacioppo, S., Bianchi-Demicheli, F., Hatfield, E., & Rapson, R. L. (2012). Social neuroscience of love. Clinical Neuropsychiatry: Journal of Treatment Evaluation, 9(1), 3–13. ↵

- Ainsworth, M. S. (1973). Infant–mother attachment. American Psychologist, 34(10), 932–937. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.34.10.932 ↵

- Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment. Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Loss. New York: Basic Books. ↵

- Ainsworth, M. S. (1973). Infant–mother attachment. American Psychologist, 34(10), 932–937. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.34.10.932 ↵

- Treboux, D., Crowell, J. A., & Waters, E. (2004). When “new” meets “old”: configurations of adult attachment representations and their implications for marital functioning. Developmental Psychology, 40(2), 295–314. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.40.2.295 ↵

- Wang, W., & Parker, K. (2014). Record share of Americans have never married: As values, economics and gender patterns change. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/files/2014/09/2014-09-24_NeverMarried-Americans.pdf ↵

- Wang, W., & Parker, K. (2014). Record share of Americans have never married: As values, economics and gender patterns change. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/files/2014/09/2014-09-24_NeverMarried-Americans.pdf ↵

- Finkel, E. J., Burnette, J. L., & Scissors, L. E. (2007). Vengefully ever after: destiny beliefs, state attachment anxiety, and forgiveness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(5), 871–886. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.5.871 ↵

- Joost, H., & Schulman, A. (2010). Catfish. Rogue. ↵

- Garcia, J. R., Reiber, C., Massey, S. G., & Merriwether, A. M. (2012). Sexual hookup culture: A review. Review of General Psychology: Journal of Division 1, of the American Psychological Association, 16(2), 161–176. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027911 ↵

- Bogle, K. A. (2007). The shift from dating to hooking up in college: What scholars have missed: The shift from dating to hooking up. Sociology Compass, 1(2), 775–788. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9020.2007.00031.x ↵

- Bogle, K. A. (2008). Hooking up: Sex, dating, and relationships on campus. New York University Press. ↵

- Garcia, J. R., Reiber, C., Massey, S. G., & Merriwether, A. M. (2012). Sexual hookup culture: A review. Review of General Psychology: Journal of Division 1, of the American Psychological Association, 16(2), 161–176. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027911 ↵

- Welsh, D. P., Grello, C. M., & Harper, M. S. (2006). No strings attached: the nature of casual sex in college students. Journal of Sex Research, 43(3), 255–267. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490609552324 ↵

- Bisson, M. A., & Levine, T. R. (2009). Negotiating a friends with benefits relationship. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 38(1), 66–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-007-9211-2 ↵

- Garcia, J. R., Reiber, C., Massey, S. G., & Merriwether, A. M. (2012). Sexual hookup culture: A review. Review of General Psychology: Journal of Division 1, of the American Psychological Association, 16(2), 161–176. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027911 ↵

- Yu, J., & Xie, Y. (2015). Cohabitation in China: Trends and determinants. Population and Development Review, 41(4), 607–628. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2015.00087.x ↵

- US Census Bureau. (2022, November 15). Living with an unmarried partner now common for young adults. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2018/11/cohabitation-is-up-marriage-is-down-for-young-adults.html ↵

- Cohen, P. (2013, June 12). Marriage is declining globally. Can you say that? https://familyinequality.wordpress.com/2013/06/12/marriage-is-declining/ ↵

- Wang, W., & Taylor, P. (2011). For Millennials, parenthood trumps marriage. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2011/03/09/for-millennials-parenthood-trumps-marriage/ ↵

- Thornton, A. (2005). Reading history sideways: The fallacy and enduring impact of the developmental paradigm on family life. University of Chicago Press. ↵

- United Nations (2013). World Marriage Data 2012. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Population Division. http://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/WMD2012/MainFrame.html ↵

- Witt, J. (2010). SOC (2010th ed.). McGraw-Hill Humanities/Social Sciences/Languages. ↵

- Trivedi, A. (2013). In New Delhi, women marry up and men are left behind. The New York Times. http://india.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/01/15/in-delhi-women-marry-up-and-men-are-left-behind ↵

- Ramsheena, C. A. (2015). Youth and marriage: A study of changing marital choices among the university students in India. Journal of Sociology and Social Anthropology, 06(01). https://doi.org/10.31901/24566764.2015/06.01.11 ↵

- Masci, D., Sciupac, E. P., & Lipka, M. (2019). Same-Sex Marriage Around the World. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/fact-sheet/gay-marriage-around-the-world/ ↵

- Gottman, J. M. (1999). Couple's handbook: Marriage Survival Kit Couple's Workshop. Seattle, WA: Gottman Institute ↵

- Carrère, S., Buehlman, K. T., Gottman, J. M., Coan, J. A., & Ruckstuhl, L. (2000). Predicting marital stability and divorce in newlywed couples. Journal of Family Psychology: JFP: Journal of the Division of Family Psychology of the American Psychological Association (Division 43), 14(1), 42–58. https://doi.org/10.1037//0893-3200.14.1.42 ↵

- Gottman, J. M. (1999). Couple's handbook: Marriage Survival Kit Couple's Workshop. Seattle, WA: Gottman Institute ↵

- Gottman, J. M., & Levenson, R. W. (1992). Marital processes predictive of later dissolution: behavior, physiology, and health. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63(2), 221–233. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.63.2.221 ↵

- Janicki, D. L., Kamarck, T. W., Shiffman, S., & Gwaltney, C. J. (2006). Application of ecological momentary assessment to the study of marital adjustment and social interactions during daily life. Journal of Family Psychology: JFP: Journal of the Division of Family Psychology of the American Psychological Association (Division 43), 20(1), 168–172. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.20.1.168 ↵