1.2 Basics of Meter: Tutorial

Meter

Can you tap along to a beat when listening to music? Most music has a pulse, which is a regularly recurring feeling of stress. Meter organizes these pulses into a recurring pattern of strong and weak beats. Each bar will have the same number of beats, unless otherwise indicated with a meter change.

Rhythms in music are the patterns of rhythmic values that exist within the meter. Meter and rhythm do not measure time, like the seconds of a clock, they measure the way notes relate to one another in terms of length.

Naming Meters and Using Bar Lines

Meters have a two-part name that includes the type of beat division followed by the number of beat groupings.

If a meter has a main beat that divides into 2 equal divisions, we call it a simple meter. For example, if the quarter note was equal to 1 beat, that beat would divide into 2 eighth notes and would be a simple meter.

If a meter has a main beat that divides into 3 equal divisions, we call it a compound meter. If a meter had a dotted quarter note as the beat, it would divide into 3 eighth notes and would be a compound meter.

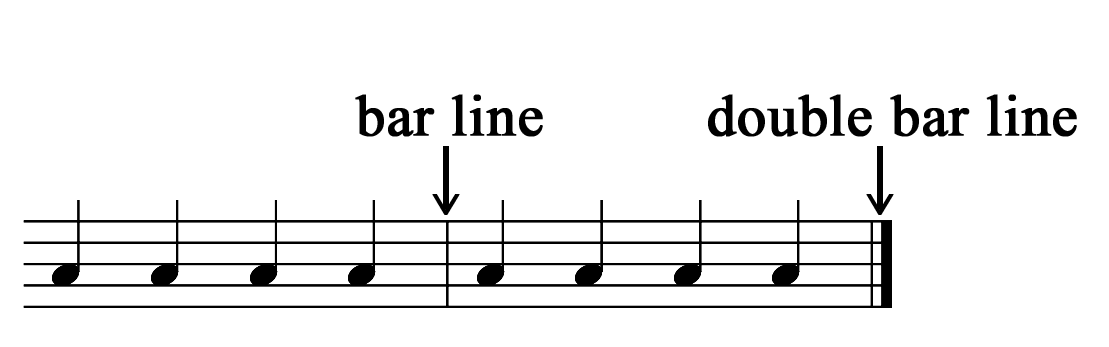

Meters are most often grouped by pulses into 2 beats, 3 beats, or 4 beats. If a meter has 2 beats per bar, we call it a duple meter. If it has 3 beats per bar we call it a triple meter, and if it has 4 beats per bar, we call it a quadruple meter. Beat groupings in music are shown using bar lines, which separate music into bars, also called measures. Bar lines extend from line 1 to line 5 of the staff, and a double bar line signifies the end of a piece.

When naming a meter with its two-part name, we say it is either simple or compound, and either a duple, triple, and quadruple meter. Knowing if a meter is duple, triple, or compound tells us how to conduct it, and how it sounds. Examples of meters can include simple duple, compound duple, simple triple, compound triple, simple quadruple, and compound quadruple.

Meter Signatures

While terms like simple duple are more general terms that can refer to multiple meters, a meter signature, also known as time signature, tell us what specific meter is being used. A meter signature is found right after both the clef and key signature at the start of a piece of music. It consists of two notes stacked on top of each other on the staff. While a meter signature bears some resemblance to a fraction, there is no line drawn between the two numbers in a meter signature. To understand what the two numbers in a meter signature mean, we have to determine whether the meter is a simple meter or a compound meter.

Simple Meters

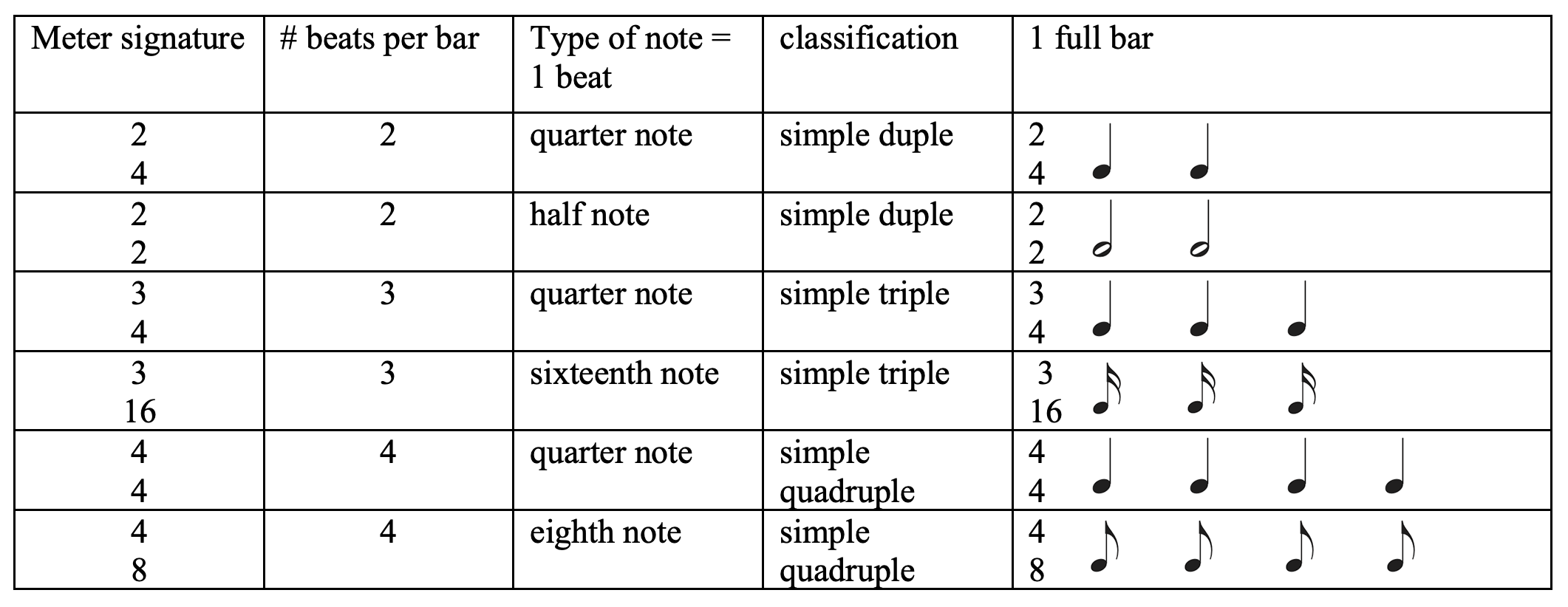

A simple meter has a main beat that divides into two equal divisions. In a simple meter, the top number in the meter signature tells us how many beats are in the bar. A duple meter will have 2 as the top number and will have 2 beats per bar. A triple meter will have 3 as the top number and 3 beats per bar. A quadruple meter will have 4 as the top number and 4 beats per bar.

The bottom number of the time signature tells us what type of note equals 1 beat. If the bottom number is a 4, the quarter note equals 1 beat. If the bottom number is a 2, the half note equals 1 beat. If the bottom number is an 8, the eighth note equals 1 beat. If the bottom number is a 16, the sixteenth note equals 1 beat. The chart below shows different types of simple meters and their key signatures.

Most often, simple meters will have top numbers with 2, 3, or 4, which can help to quickly identify them.

Compound Meters

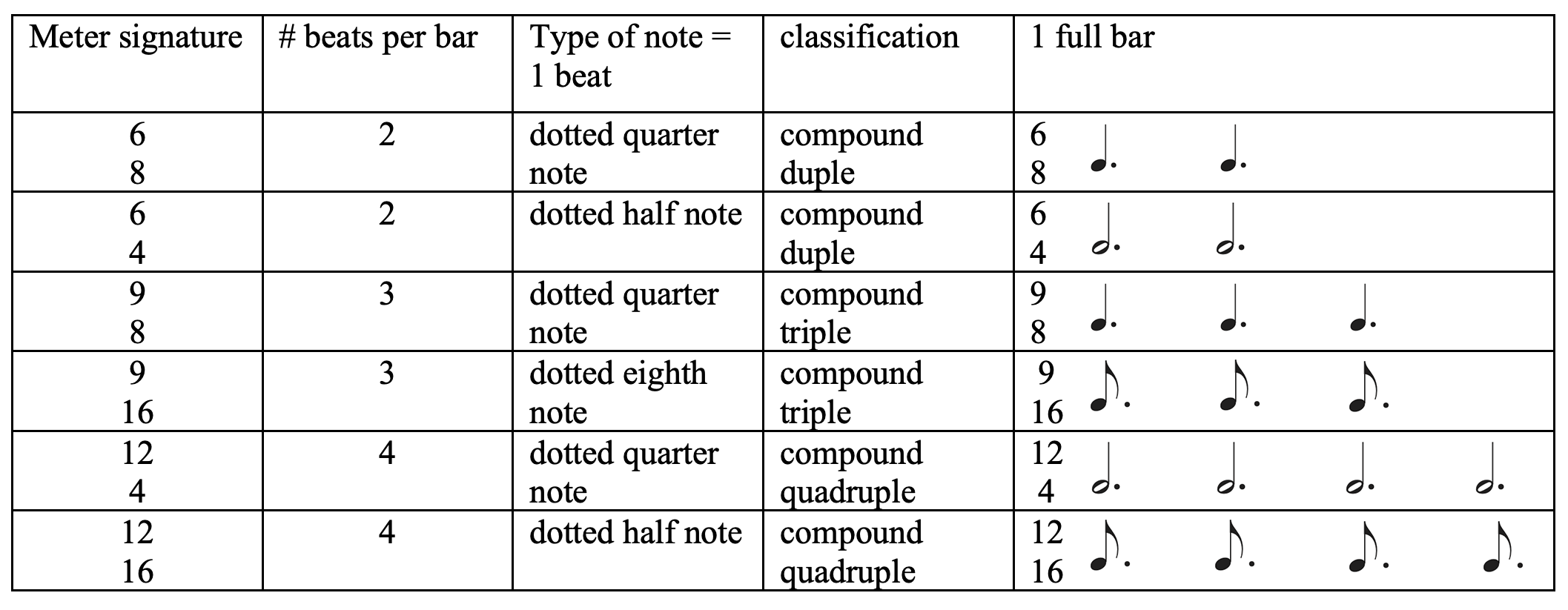

A compound meter has a main beat that divides into 3 equal divisions. Meter signature numbers work differently for compound meters than for simple meters. In a compound meter, the top number is the number of divisions of the beat that are in 1 bar. In order to find the number of beats per bar, you divide that top number by 3 because each beat is divided into 3 notes. If the top number is a 6, you divide 6 by 3 and get 2. So, a 6 as the top number is a duple meter with 2 beats per bar. If the top number is a 9, it is a triple meter with 3 beats per bar. If the top number is a 12, it is a quadruple meter with 4 beats per bar.

The bottom number of a compound meter signature in also differs from simple meter. The bottom number in a compound meter signature tells you what type of note equals 1 beat division. In order to find the note that equals 1 beat, you have to remember that you have 3 beat divisions per beat, and add 3 of the type of note indicated together. So, if the bottom number is an 8, you add 3 eighth notes together to find that the beat is equal to 1 dotted quarter note. If the bottom number is a 4, you add 3 quarter notes to get a beat of a dotted half note. If the bottom number is 16, you add 3 sixteenth notes to get a dotted eighth note as the beat. The chart below shows different types of compound meters and their key signatures.

Identifying Meter Signatures

While both simple and compound meters can use the same numbers for the bottom number in the meter signature, the top number can help you quickly identify if a meter is simple or compound. Most often, simple meters will use 2, 3, or 4 as the top numbers. Compound meters most often use 6, 9, or 12 as the top numbers. Looking at the way the rhythms are beamed in the bar can also help you identify which meter is being used, and will be explored further in the chapter on beaming.

Accent Scheme in Meter

As we know from our definition of meter, meter organizes the regularly recurring pulses in music into a recurring pattern of strong and weak beats. One measure or bar in music equals one complete cycle through the pattern of beats. Music that has 2 pulses is called duple meter. In duple meter, the downbeat, or first beat of the bar is the strongest, and the second beat is weaker. In a quadruple meter, there are 4 beats in the bar. The downbeat is the strongest beat, followed by a weak second beat, the third beat is strong (but not the strongest), and the fourth beat is weakest. Notice that all four beats have a different accent strength. In triple meter, there are 3 beats. The downbeat is the strongest, beat 2 is weak, and beat 3 is the weakest beat. Understanding accent scheme can help us to hear whether a piece is in duple, triple, or quadruple meter. Other factors combined with meter, like phrasing and harmony, can also help us distinguish between meters. Listen to the following examples to hear the meter.

simple quadruple or simple duple

simple triple

compound duple or compound quadruple

simple quadruple or simple duple

simple triple

compound triple

To dive more into how meter plays an integral part in music, look at the music you are currently working on, or would like to learn more about, and think about the following questions:

- Can you hear the accent scheme for the meter signature?

- Why do you think the composer chose that specific meter? What kind of feelings does that meter signature invoke that might change if a different meter signature were used?

- Look at other pieces in the same meter. What elements highlighted by the meter are similar and different to your original piece? Do they have a similar feel?

- Is the piece written for a certain purpose that traditionally uses a specific type of meter (like a dance)?

- What would be different and how would the music sound and look different if they had chosen to use a different beat level or a different number of beats (like in 2 beats instead of 4 beats)?

- What would be different, and how would the music sound and look different if the composer had chosen to use a different subdivision (like compound meter instead of simple meter)?