6.1 Functional Harmony: Tutorial

Functional Harmony

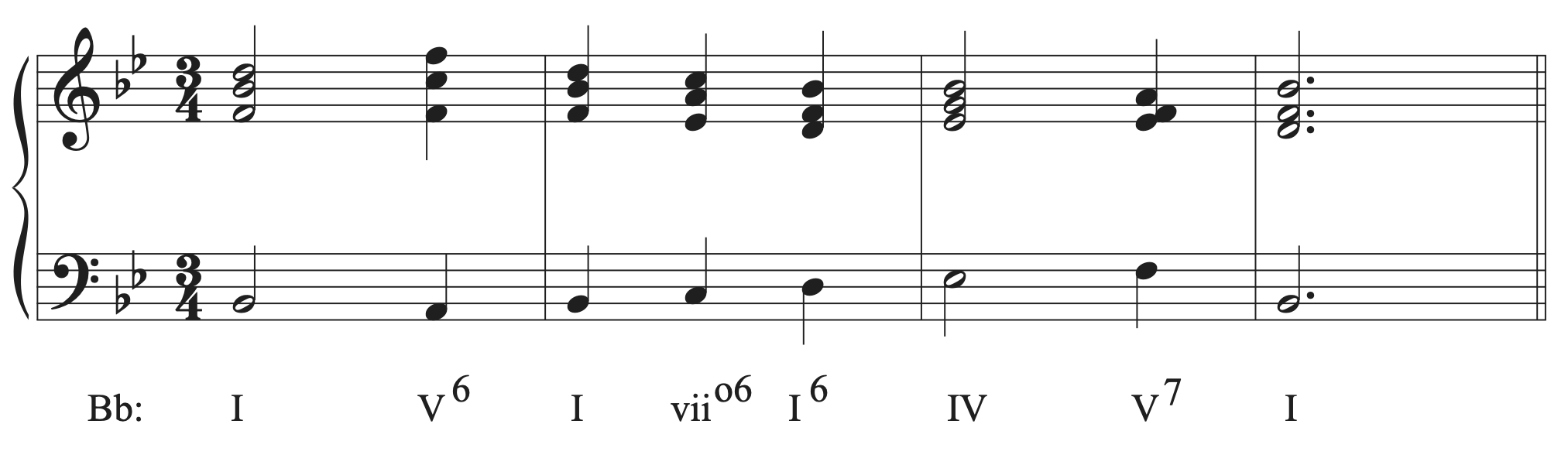

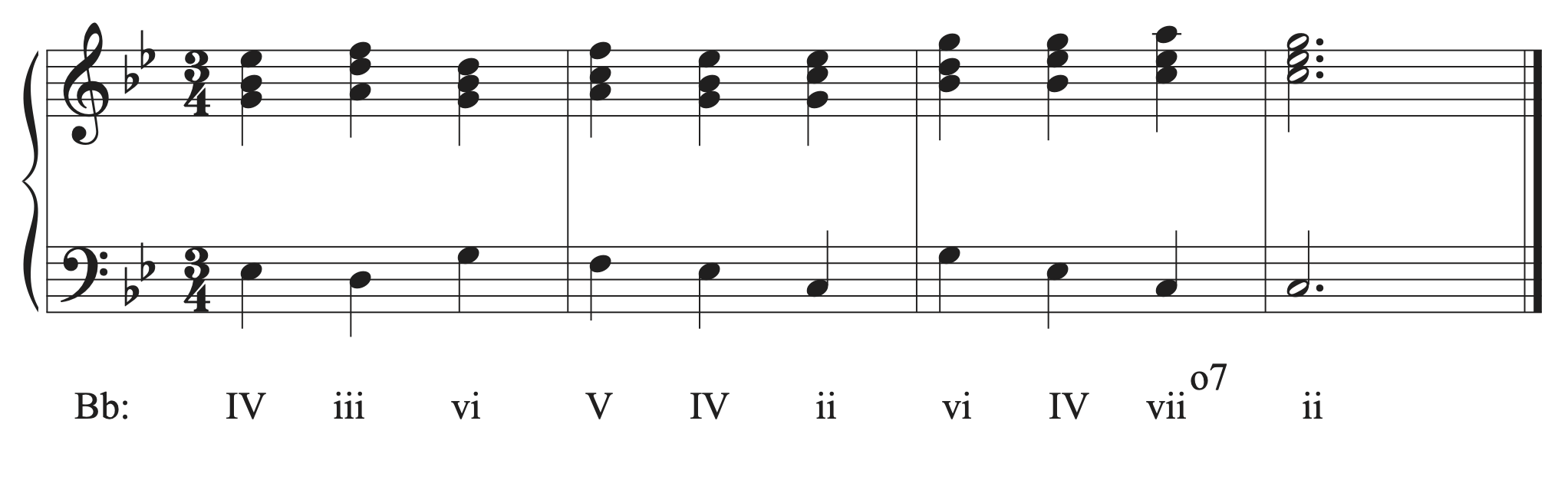

Functional harmony in tonal music centers around the idea that tonic serves as the “home base” in a key and chords built on each scale degree in the scale have predictable relationships with each other and predictable movements as they ultimately progress towards tonic. Each chord in a key has its own level of status, behavior, and stability. Expected progressions between chords make the music we hear make sense to our ears. Compare the following two examples. The first is written with a chord progression that follows expected motions, ultimately progressing towards tonic. You should have no trouble singing tonic after listening to the example. The second example, however, obscures the expected progressions found in music in such a way that our ears have trouble recognizing where tonic is and understanding where we are in the progression at any time.

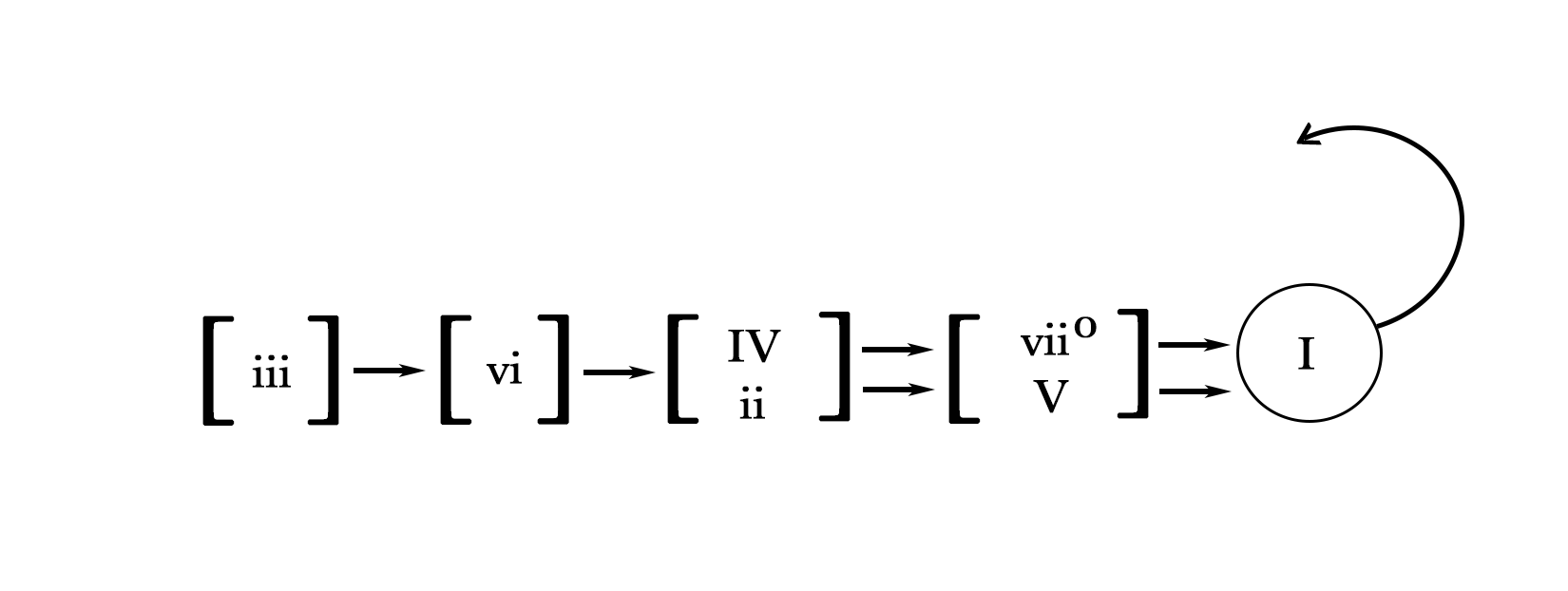

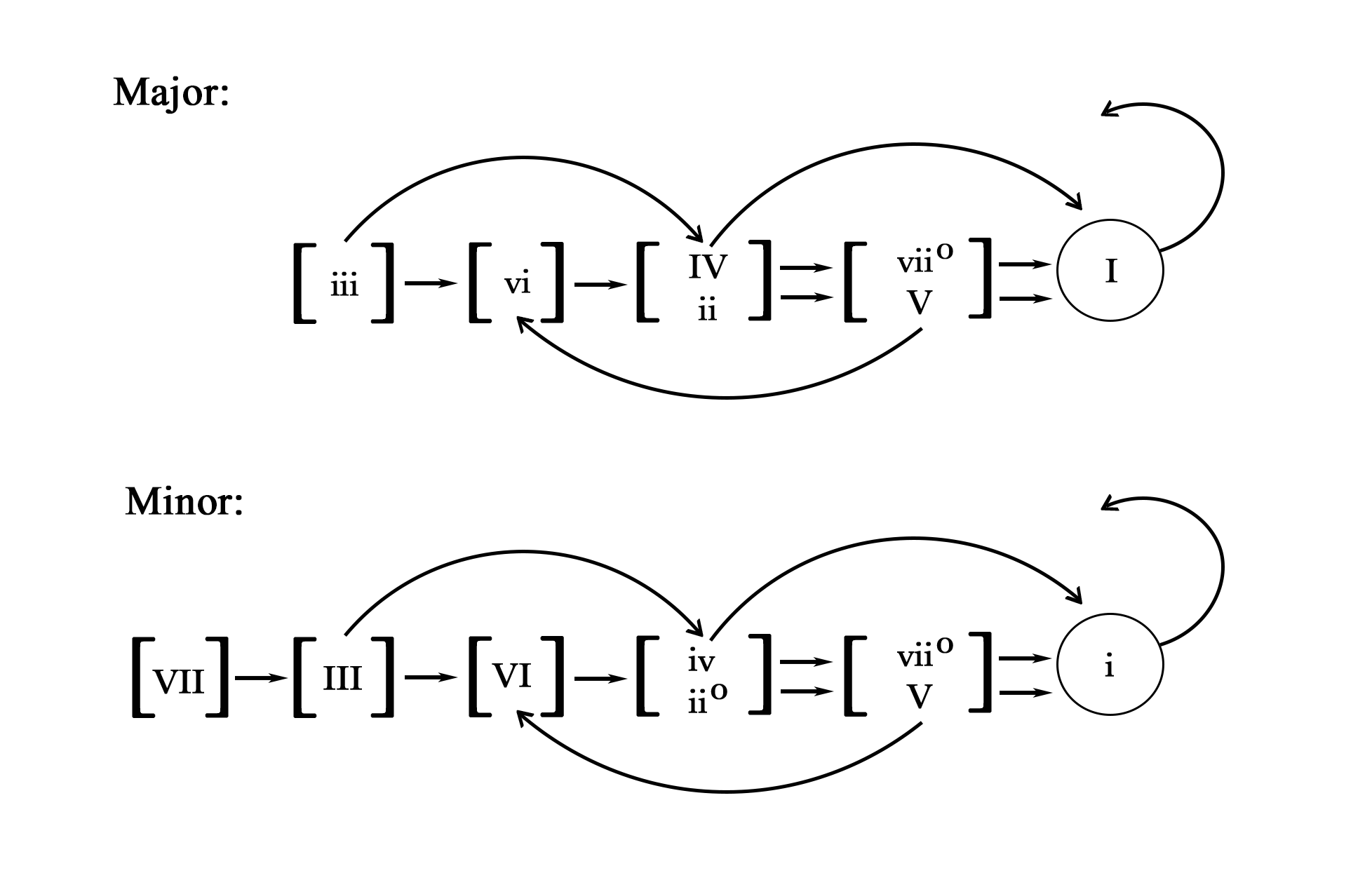

Functional Harmony Chart

Chords built on each scale degree in a key can be grouped into categories that share a common function. Putting each category into a functional harmony chart shows the relationships between the chords and categories. We will examine individual chords in more detail in later chapters. We’ll draw the functional harmony chart in major first, and then show the differences in minor.

Tonic category

Tonic is the ultimate goal in tonal music. It is home base in a key, and has the most stability and flexibility. Tonic can move to any chord. Because it is the goal of motion, it will be the last chord on the functional harmony chart, so we will draw the tonic chord on right-hand side of the chart.

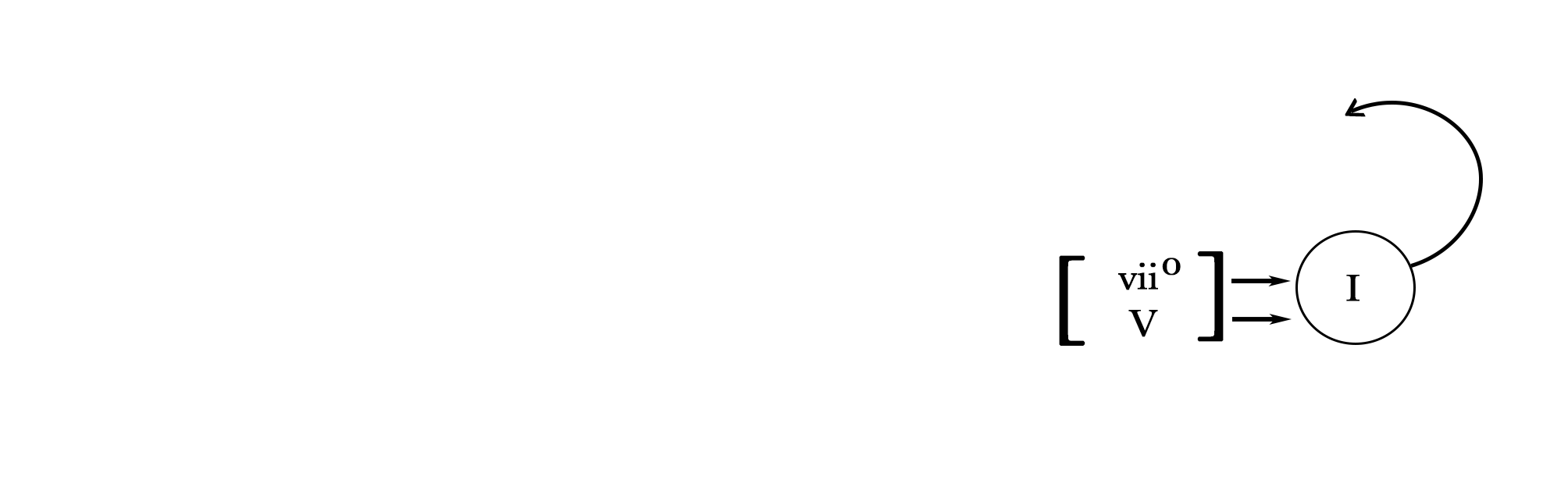

Dominant category

Chords in the dominant category most often directly precede tonic. Dominant function chords include V and vii˚. The leading tone, a tendency tone that wants to resolve to tonic, exists in both chords in the dominant category. The dominant category chords are drawn within a bracket to show that they are part of the same category and have arrows that show that both chords can go to tonic. Chords can move within the same category, however, it is more common for vii˚ to move to V, rather than for V to move to vii˚. Notice that the tonic category is contained within a circle instead of a bracket. That is done deliberately to show that tonic is different from the other categories because tonic is both home base and the most flexible chord. It can move to anything.

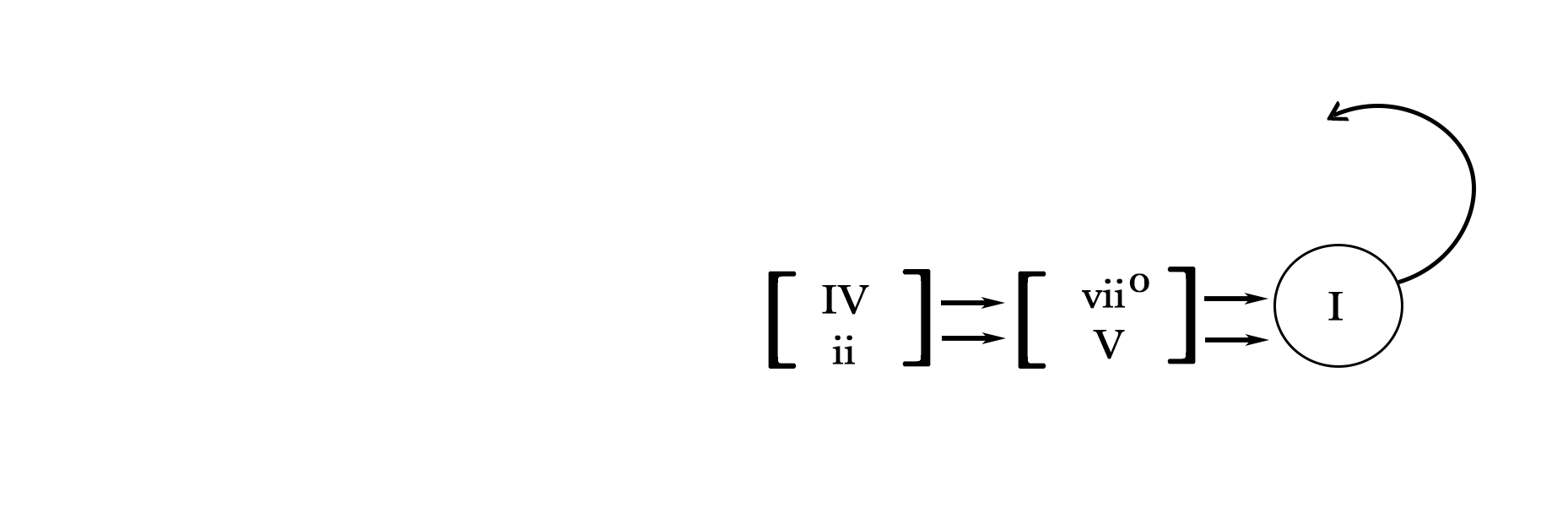

Predominant category

The predominant category comes before the dominant category on its way to tonic. The two chords contained in the predominant category are IV and ii. Like progressing from dominant to tonic, moving from predominant to dominant to tonic is one the most fundamental and frequently used progressions in music. Like the dominant category, both chords are contained within a bracket with arrows to show that both chords can move to either chord in the dominant category. The chords can move within the same category, however, it is more common for IV to move to ii rather than for ii to move to IV.

Intermediate harmonies

The two remaining diatonic chords, vi and iii, act as intermediate harmonies but are not grouped together into one category. The vi chord precedes the predominant category, and the iii chord precedes the vi chord on the chart.

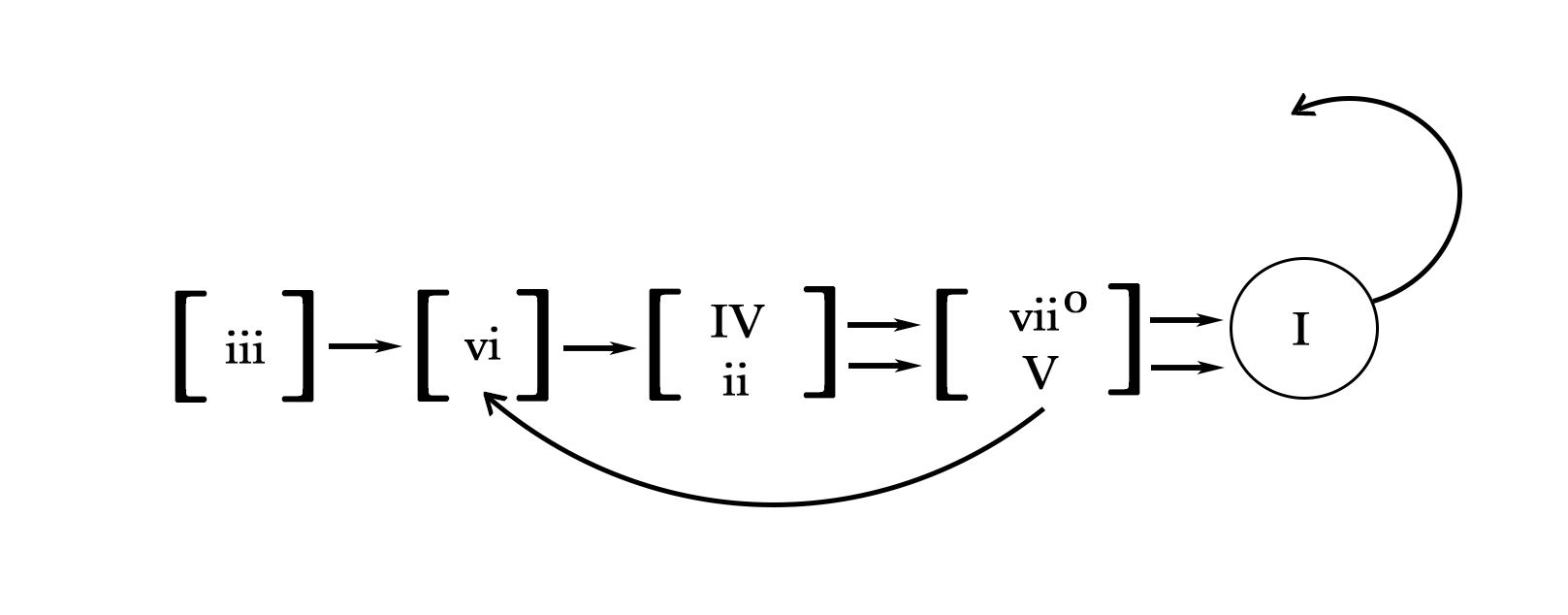

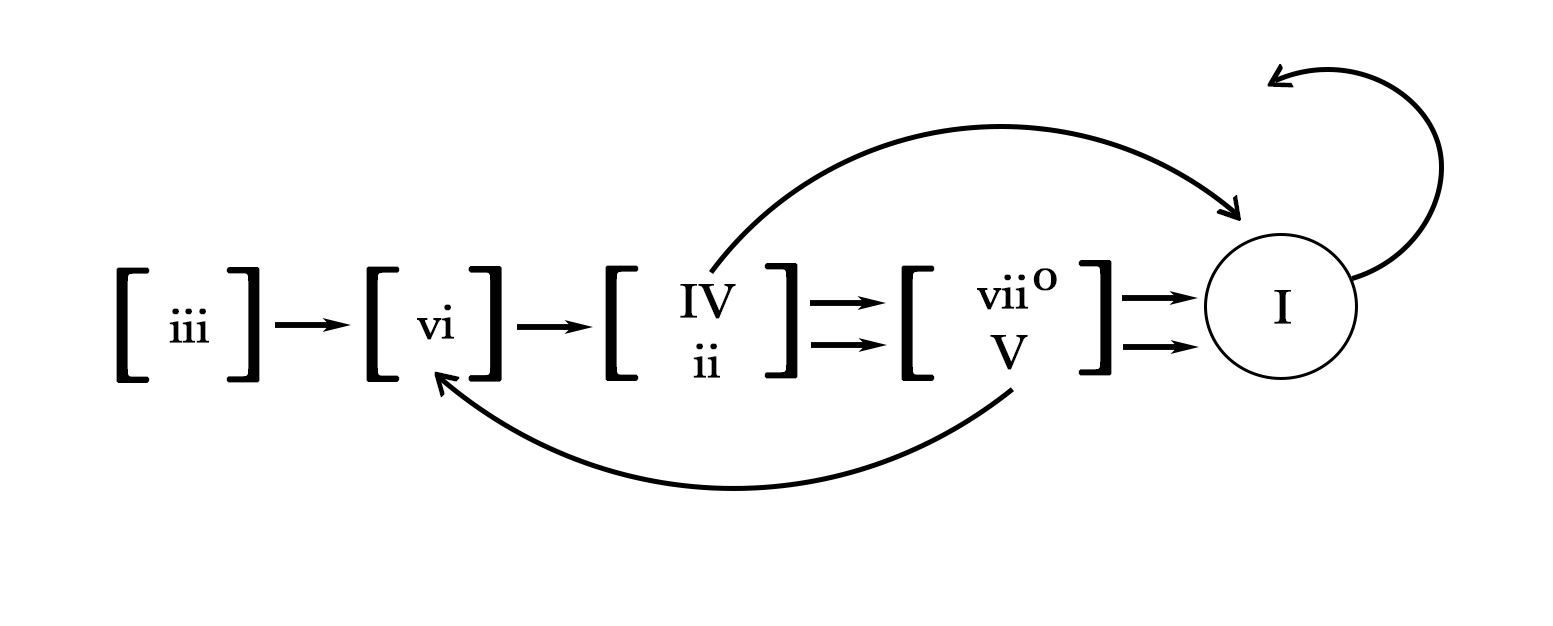

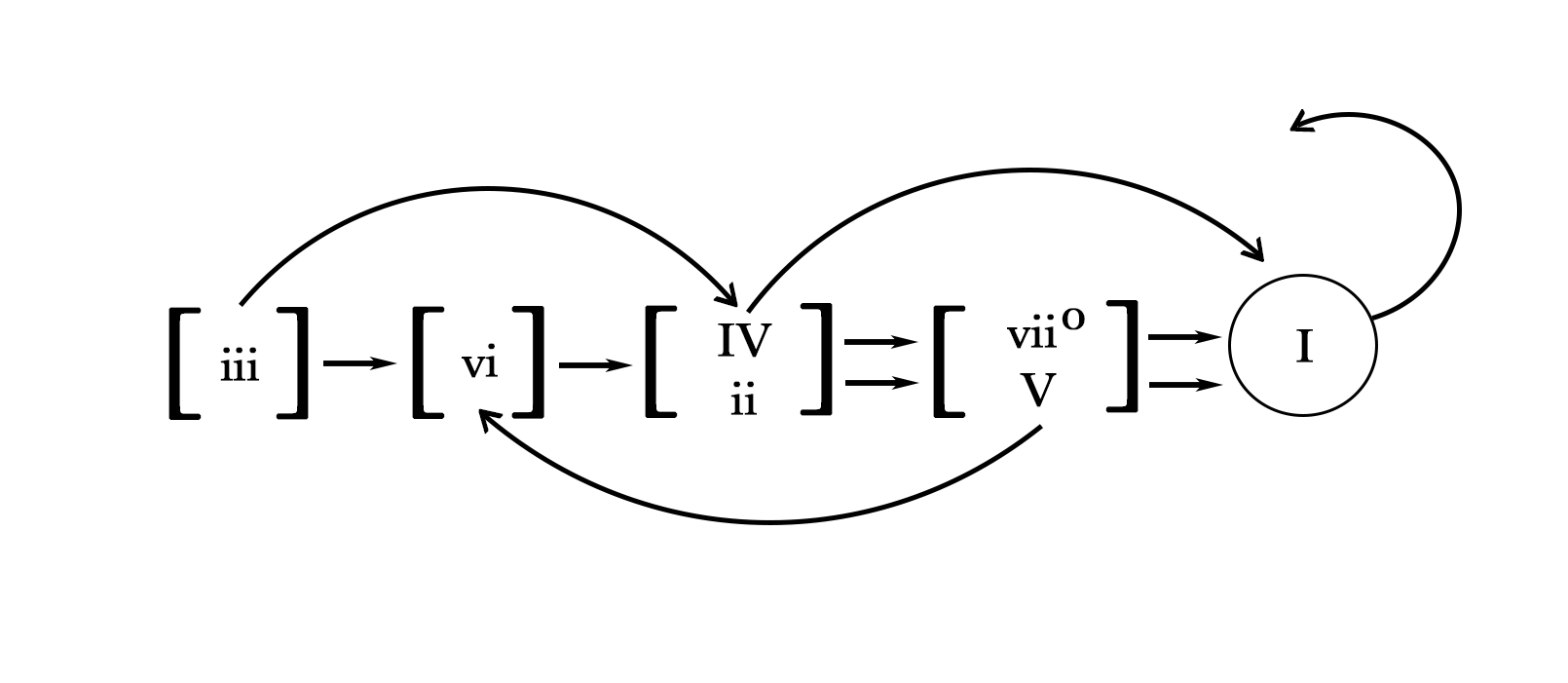

Addition common types of motion

In addition to forward motion from left to right on the chart, there are three common types of motion between chords that can be indicated on the chart.

The first arrow that we can add to the chart is from V to vi, which is called deceptive motion because the vi chord acts as a temporary substitute for I. Though we commonly see this motion at a deceptive cadence, this type of motion is not limited to cadences and can be used internally in phrases. We draw the arrow from the V chord to the vi chord on the chart. Note that this arrow only moves in one direction, as vi-V is not a common enough motion to include on the chart. Also note the arrow is specific to the V chord and that vii˚ does not commonly go to vi.

The second arrow we can add to the chart is from IV to I. IV to I is another type of cadence pattern called a plagal cadence. We will learn more about the plagal and deceptive cadences in the chapter on cadences.

The last arrow we will add to the chart goes from iii to IV. The iii chord shares two notes with tonic chord and can sometimes be substituted for tonic in a progression (like the vi chord). Though the iii chord contains a leading tone, it is not a dominant function chord, so the leading tone does not need to resolve to tonic and may descend to scale degree 6, which is often part of a IV chord, allowing iii to move to IV. Keep in mind that iii goes to IV on the chart, but does not go to ii.

The functional harmony chart in minor

The functional harmony chart is almost the same in minor. The chord qualities change to reflect the diatonic chords found in a minor key. The other change is the addition of VII to the beginning of the chart. The subtonic chord is the result of not raising the leading tone on scale degree 7. The leading tone is essential to establishing the dominant category in a minor key (notice that the dominant category is the only category on the chart that is exactly the same in both Major and minor). Using VII in a prominent way can undermine the tonality of a minor key. It frequently is used to move to the relative Major key (III). The subtonic chord is on its own at the beginning of the chart.

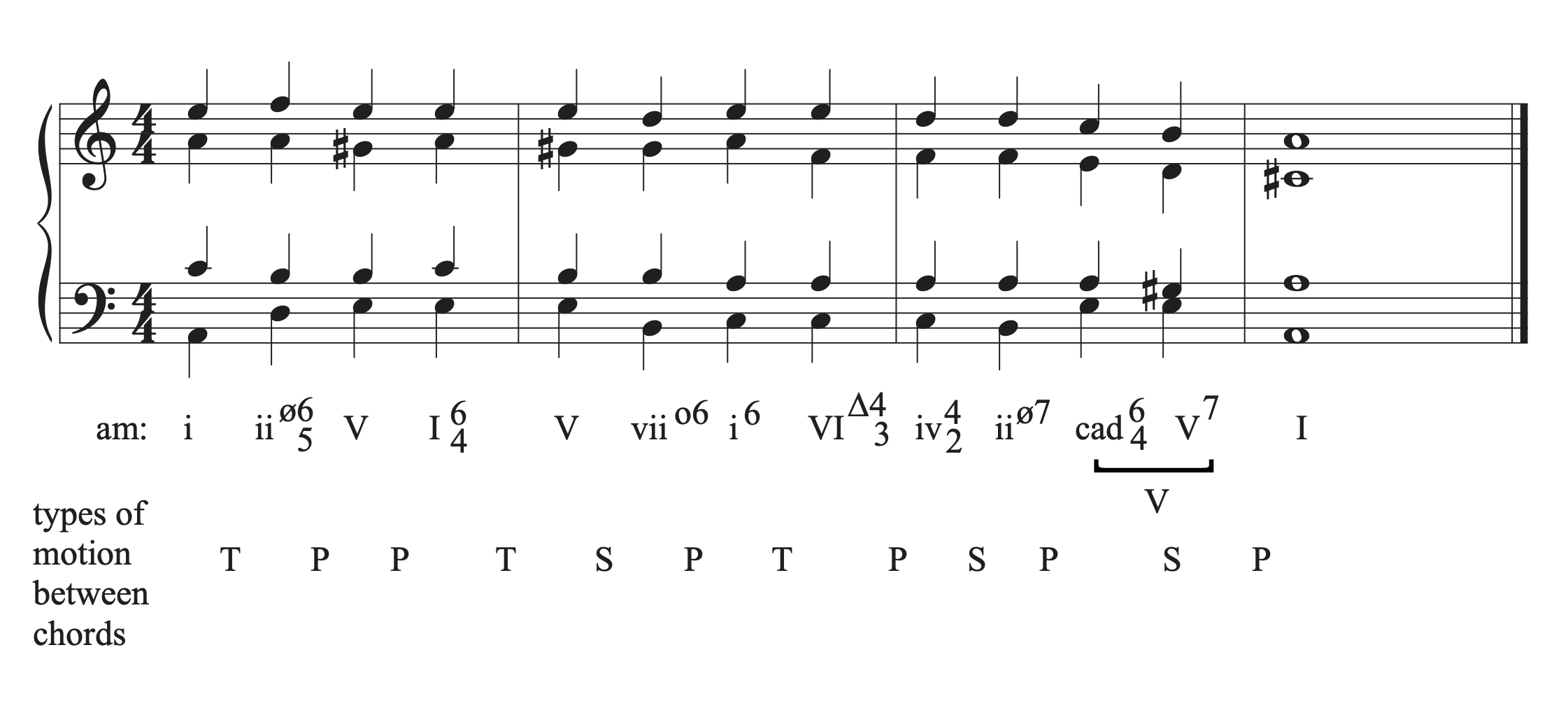

Types of Motion Between Chords

There are five types of motion possible between chords.

- Progression (P): forward motion on the chart by 1 category

- V-I is an example of progression

- Tonic (T): motion from tonic to any other chord

- Retrogression (R): moving backwards on the chart by one or more categories

- V-vi and vi-iii are examples of retrogression

- Similar Motion/Repetition (S): motion within a category

- ii-IV, vii˚-V, and vi-vi are examples of repetition

- Elision (E): forward motion on the chart, skipping one or more categories

- IV-I and vi-V are examples of elision

Seventh Chords

Seventh chords function in the same categories as their triad counterparts. Seventh chords are often used to substitute for their triad counterparts. I∆7 is an exception to this substitution. Tonic is home base, the goal of motion, and very stable. Once a seventh is added to a chord it creates a tendency tone that must resolve. Therefore, I∆7 is not a good choice as a substitute for a stable I chord and should be used as decoration instead of structurally.

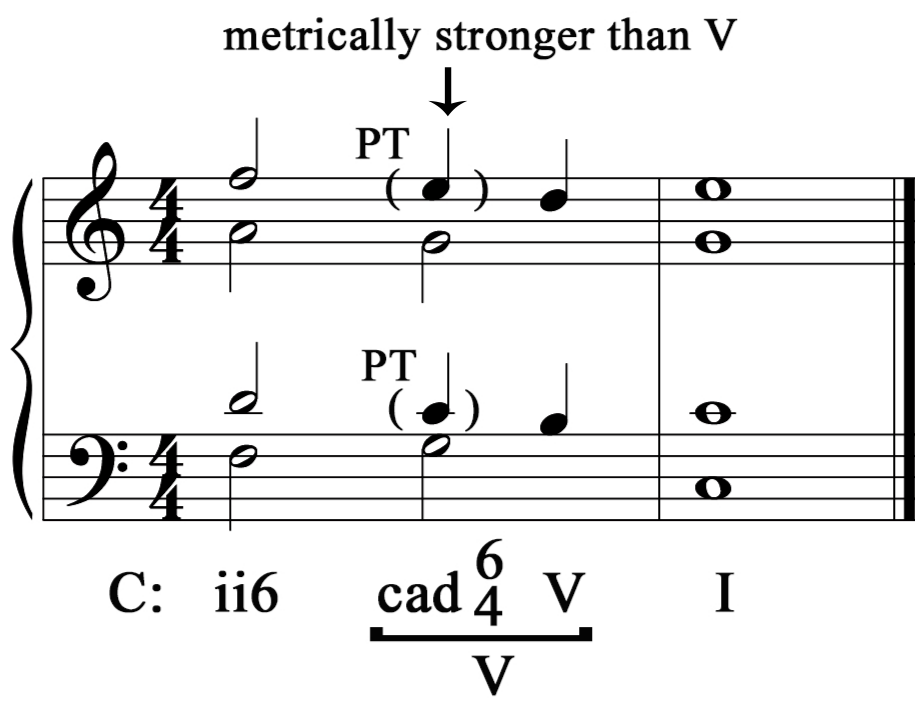

The Cadential 6/4 Chord

Root position and first inversion chords can often be used interchangeably in music. Second inversion chords, however have a very different function. They exist as chords that result from embellishing the more structural chords around them. Though 6/4 chords will be discussed in detail the chapter on part writing with second inversion chords, the type of 6/4 chord called the cadential 6/4 chord bears discussion in this chapter because it can have two functions. The cadential 6/4 is a tonic chord in second inversion. It serves as a tonic chord when used within a phrase to embellish the chords around it, but it can also serve as a dominant function chord when it decorates a V chord at a cadence. This distinction becomes important when labeling the types of motion between chords. Let’s look at how a cadential 6/4 chord is constructed.

In this progression, ii6 moves to V before cadencing on I. When ii6 moves to V, two non-chord tones called passing tones pass between the two chords in the soprano and tenor voices. If we analyze the chord produced by those two non-chord tones along with scale degree 5 in the V chord, we see that the notes are C E G, which spell a tonic chord. This type of motion, used to decorate V at a cadence, is the most common use of a second inversion triad in music. Though the notes spell a tonic chord, they really serve to provide decoration for the V chord that follows. Therefore, we consider a cadential 6/4 chord to be a V chord with decoration, meaning it functions like a dominant chord. This type of dominant function 6/4 chord is only found at a cadence directly before a V chord. If we see a I6/4 chord when analyzing music, we have to consider whether it is functioning as a tonic chord or as a dominant chord. If it is functioning as a tonic chord, we label it I6/4. If it functioning as a dominant chord at a cadence, we chance the label to cad6/4 on the I6/4 chord and bracket both the cad6/4 and V chords with a V underneath to show that both chords are really functioning as a V chord (Note that there are other variations of this label that you might find in music in other sources). Let’s look at an example in music to see how tonic function I6/4 differs from dominant I6/4 in terms of labeling types of motion between chords.

Analyze the music you are currently working on or studying using Roman numerals. For any chords that you don’t yet know how to analyze, simplify them into triads or seventh chords for this exercise. Look at your chord progression in terms of functional harmony categories and types of motion between chords. Are the chords following an expected progression? Does your analysis of the motion between chords match the sound of the music? Are there moments that sound easier to listen to than others? How does adding an analysis to your music affect the way you think about it when you practice? Do you hear things differently now that you’ve dived in a little deeper? What stands out that you didn’t notice before? What new questions about the composition arose from working on a chordal analysis? What type of labeling system do you think would make the most sense for studying the piece you are working on: lead sheet symbols, figured bass, or Roman Numerals?