11.2 Harmonizing a Melody with Root Position Triads: Theory exercises

In addition to Workbook Chapter 11.2, see the example below.

Let’s look at an example of harmonizing a melody with root position chords. Listen to how the melody sounds. Think about melodic phrasing, cadences, and harmonic rhythm. When do you hear chord changes? When do you hear pauses and endings in the music?

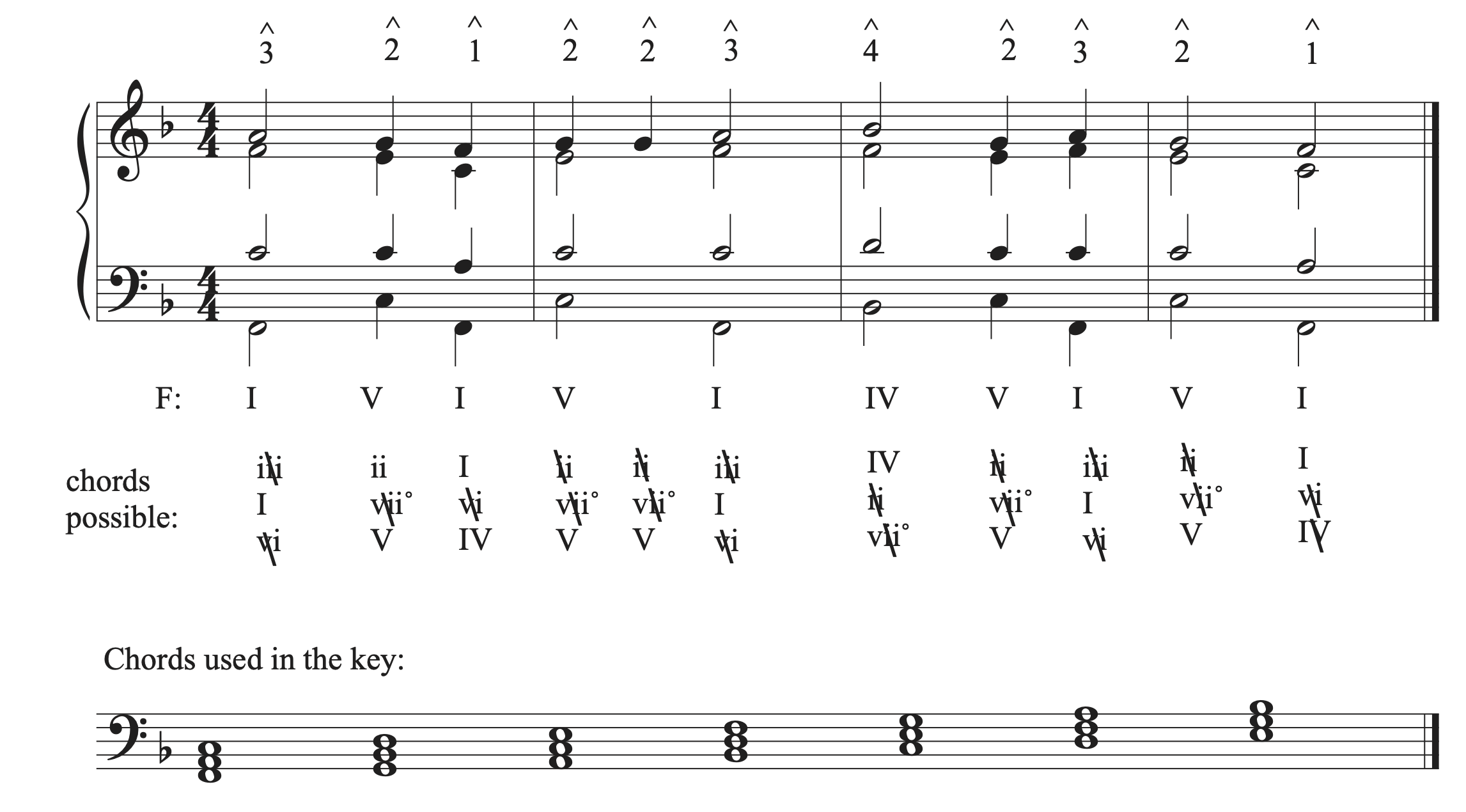

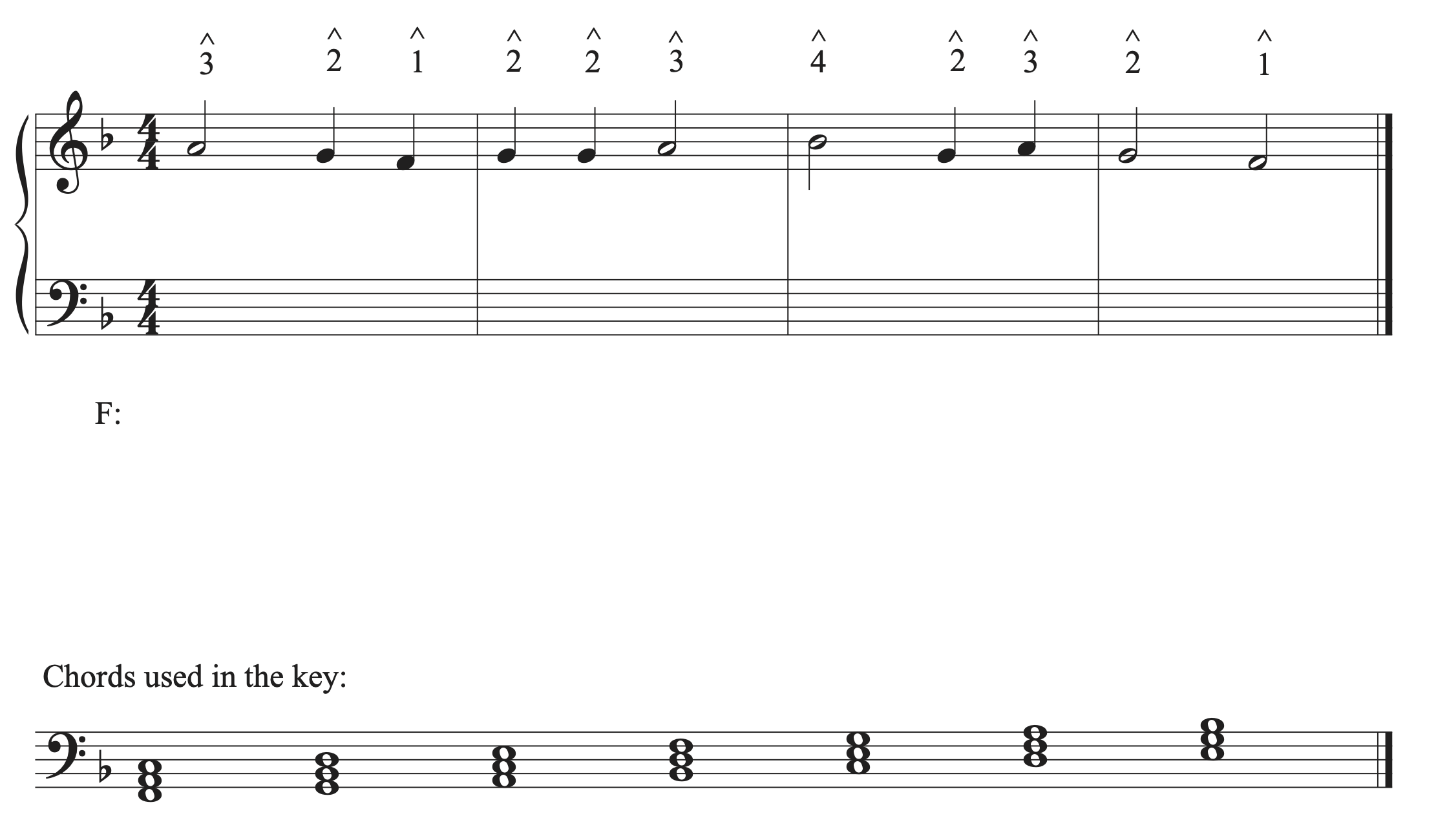

Our first steps are to label the key, write the chords used in the key in root position, and write in the scale degrees in the soprano voice.

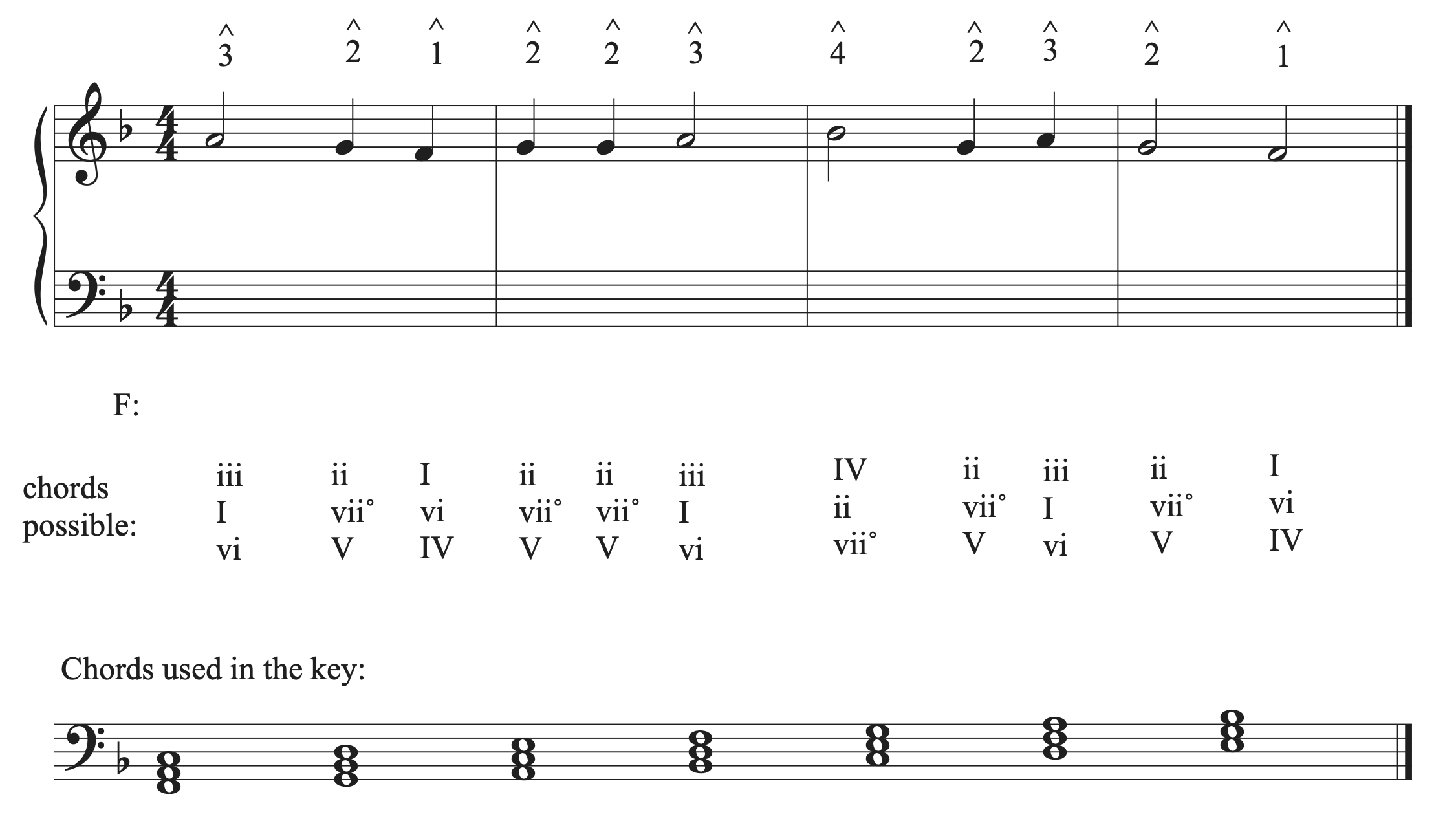

Next, create a list of the three possible chords that can be supported by each scale degree. Each scale degree could be the root, 3rd, or 5th of a chord. Start with the chord built on the scale degree. Then count backwards two chords in the scale in order to find the next chord. Then count two chords backwards in the scale to find the last chord. Our melody begins on scale degree 3: A. Our first chord is a iii chord. The next possible chord is a I chord (2 backwards from iii), and the last possible chord is vi (2 backwards from I). Fill in the rest of the chord choices.

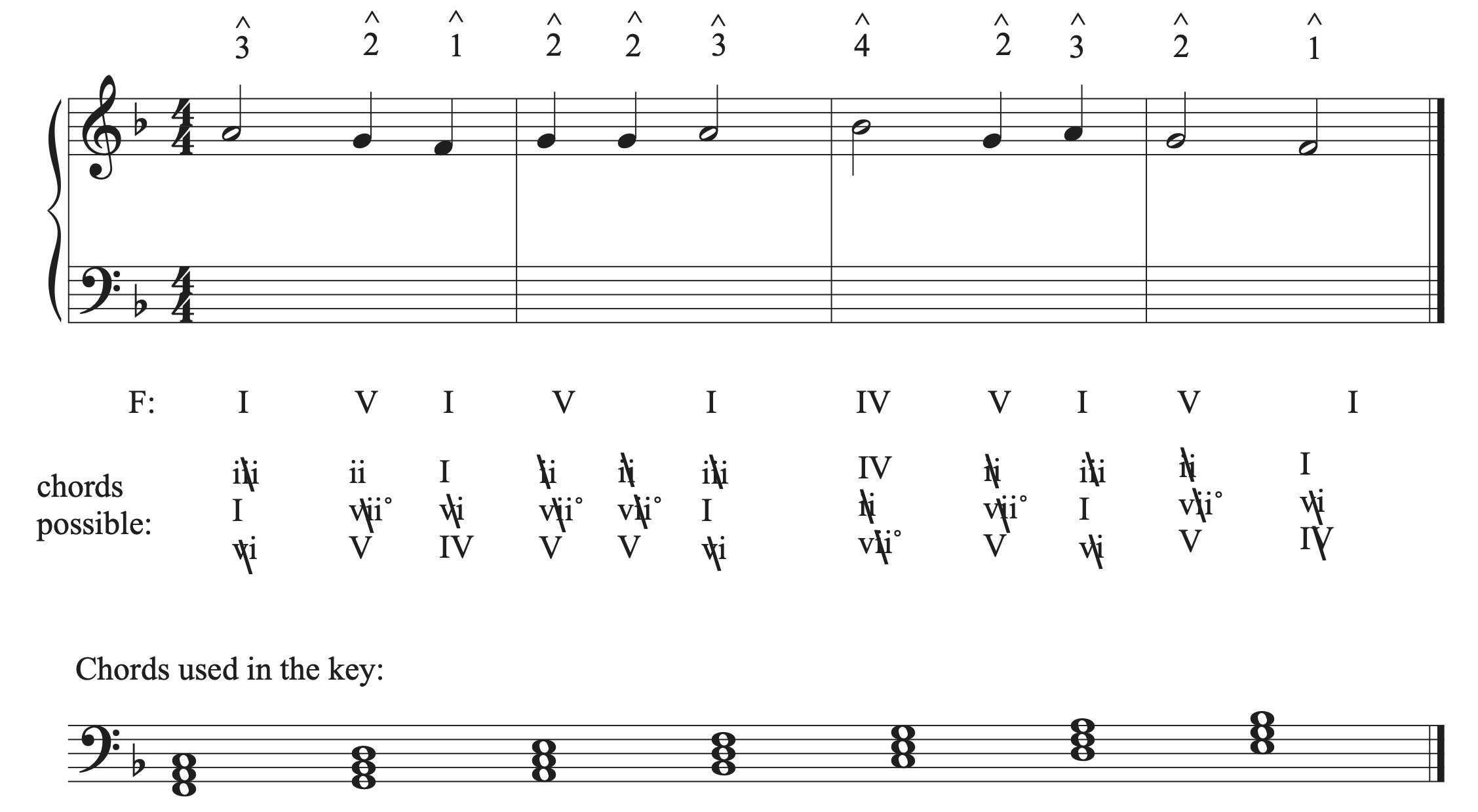

The next step is to eliminate any chords from the list that we can’t use. Determine the melodic structure, phrasing, cadences, and potential harmonic rhythm choices. Then, look at functional harmony to eliminate choices. We can eliminate all iii and vi chords because we are not using them in our root position progressions. We can then look at the first and last chords. They should be I chords, so we can eliminate all other choices. We can then look at the cadence chords. This 4-bar progression has two halves. Bar 2 has a pause in the music and needs a weaker cadence than the cadence in bar 4, which should be a strong, conclusive cadence. In order to create a PAC in the last bar, we need a V-I progression. Bar 2 also ends on I, and since we are not using vii˚, V is the only chord on beat 2 that can go to that I chord. Remember that ii does not go to I so can be eliminated as a choice. Though both cadences use the same chords in the same metric position, the final cadence uses 1 in the soprano, which makes it stronger than the cadence in b. 2. Always plan for cadence strength when harmonizing a melody.

The next step is to choose a chord progression that works with the phrasing, cadences, harmonic rhythm, and uses good functional harmony. After eliminating chord choices, the second half of the melody only has one choice for a chord progression:

- IV V I V I; harmonic rhythm: half note, quarter note, half note, half note

Let’s choose a progression for bars 1-2 that works with the progression for bars 3-4. Our choices are:

- I ii IV V I; harmonic rhythm: half note, quarter note, quarter note, half note, half note

- I V I V I; harmonic rhythm: half note, quarter note, quarter note, half note, half note

Both progressions share the same harmonic rhythm, which matches nicely with the harmonic rhythm for bars 3-4. Out of the two choices for progressions for bars 1-2, one works better in terms of functional harmony than the other. When we have repetition between chord in a category, like the predominant category, one of those chords usually moves to the other much more often than the reverse motion. In the predominant chord category, IV is much more likely to move to ii than ii is to move to IV. On the other hand, I V I V I is the most fundamental motion in music, even if it not the most interesting progression to use without the help of inversions to smooth out the bass line and provide variety. For those reasons, we will choose the tonic-dominant progression.

Once we have chosen a progression, the next step is to write in the bass voice and check it for errors against the soprano voice. If errors exist, it is good to catch now when it is easier to re-work the progression. If you part writing all of the voices and then find an error that causes you to change the progression, it will take much more time and work to redo.

Once the bass voice has been checked against the soprano, we can part-write the remaining voices. Let’s review the considerations and steps for part writing.

Considerations for Part Writing (review)

- Common tones

- Retain common tones when possible

- If there are no common tones, try to move the upper voices in contrary motion to the bass voice.

- Complete vs. incomplete chords

- A complete chord has all chord members present. Complete chords are preferred to incomplete chords.

- An incomplete chord is missing a chord member. Most often the 5th is omitted and the root is doubled or tripled. Chords with tripled roots appear at cadences, not within the phrase.

- General Doubling rules

- Do not double tendency tones and more active scale degrees (like the leading tone or the chordal seventh)

- Double the root (bass) of the chord in root position major and minor chords (except when going V-vi, in which case the 3rd of the vi chord is most often doubled. See more about the V-vi progression below).

- Diminished chords are most often used in first inversion with the 3rd of the chord doubled. It is best to avoid root position diminished chords when possible because their interval structure often creates part writing errors like parallel and unequal 5ths with other chords. If a diminished chord must be used in root position, always double the 3rd of the chord to minimize the chances of part writing errors.

- Think horizontally at all times to create smooth lines in each voice, especially in the soprano. Avoid leaps larger than a 3rd, but if a larger leap is used, it should be filled in by step in the opposite direction.

- Resolve tendency tones (like the leading tone and chordal seventh). A leading tone in the soprano should always resolve to tonic. A leading tone in an inner voice may move down to scale degree 5, though make you should make an effort to resolve it to tonic when possible. Leading tones in the bass resolve to tonic unless they switch voices when moving to another dominant chord. In that case, they should resolve to tonic in the new voice.

- Check for part writing errors. Always check each chord for doubling and spacing errors and check each chord connection for other part writing errors (like parallel 5ths and octaves). In addition, check that you have spelled the intended chord with the correct notes and accidentals, and that all notes in the chord line up together vertically.

Summary of part writing steps

- Write the names of the notes found in each chord using correct doubling and accidentals.

- Voice the first chord using generous spacing between voices while keeping voices in their respective ranges. Plan to have the soprano move by step. Check for doubling and spacing errors before connecting chords.

- Connect chords:

- If there are common tones, add those in first. Then move each voice to the closest note in the next chord using smooth, stepwise motion when possible.

- If there are no common tones, move all upper voices in contrary motion to the bass.

- V-vi progressions will not follow a. or b., so move each voice to the closest note in the next chord.

- Check for part writing errors.

Part-write the remaining voicing in the progression following the guidelines above. Then, compare your answers to the completed example below.