9.1 First Species Counterpoint: Tutorial

What is counterpoint?

Counterpoint refers to two or more melodies that combine to make a consonant whole. The rules of counterpoint, which have varied over time, govern the use of dissonant intervals between the melodies to accomplish this goal.

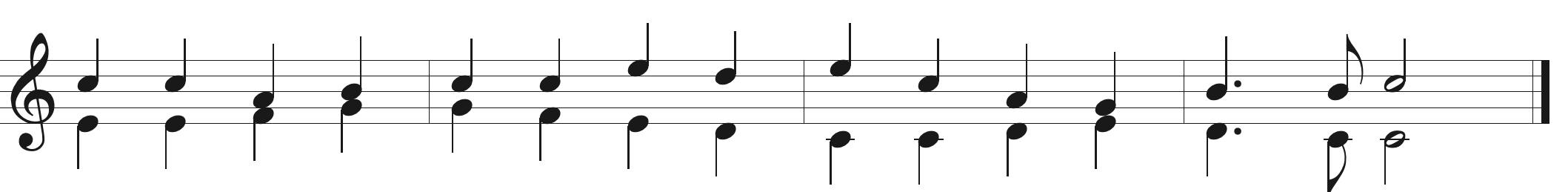

Example 1: Woody Guthrie’s famous song, “This Land is Your Land” with a countermelody below.

- Play or sing the countermelody (the lower part) by itself: a pretty decent melody, right?

- Now, play both parts together and listen: Not so great!

Example 2: a countermelody to “This Land is Your Land” following proper counterpoint rules.

- Play or sing the countermelody (the lower part) by itself: a good melody in and of itself.

- Now, play both parts together and listen: Hear how they work well as counterpoint

When and where did counterpoint develop?

Developed in 15th Century Italy. Codified in the 16th-century high Renaissance. In this class we will not study the history of counterpoint or complex rules as developed by Renaissance musicians. Rather, we will explore the basic rules of organizing consonances and dissonances between two melodies that persist in many styles of Western classical and popular musics to this day.

Why is it important to study counterpoint in the 21st-century?

The general approach to counterpoint we will be learning in this class provides a window into how musicians have created multi-part music, from Bach’s predecessors to contemporary rock, jazz, pop and hip-hop. More importantly, a rudimentary understanding of counterpoint will allow you to more effectively create interesting and effective music.

How does one create counterpoint?

Counterpoint is all about managing consonance and dissonance between two voices.

- Consonant intervals include 3rds, 6ths, and perfect 5ths unison and the octave.

- Dissonant intervals include 2nds, 7ths, 4ths and the tritone.

It may at first seem strange to our modern ears to think of the perfect 4th as a dissonance. In short, this is because the 4th creates a downward pull in the upper voice, wanting to resolve down to a third (think, 4-3 suspension). This is in part the reason why harmonies with a 4th above the bass (i.e. 6/4 chords) are inherently unstable and are only used in certain circumstances.

Species counterpoint

Early musicians considered counterpoint from the perspective of rhythm and duration between two melodies. For example, two melodies could have the exact same rhythm throughout (such as a homophonic hymn), or one melody might have two, three, or four different notes while the other holds a single pitch. Different ratios of rhythmic value, not the absolute values themselves, predicate different rules for use of consonance and dissonance.

Such rhythmic ratios and the rules of consonance and dissonance they entail were codified into different “species”.

First Species, 1:1

Note-against-note, both parts have the exact same rhythm.

- Consonances only. Every vertical interval between the parts must be a consonance. In other words, you should never have a 2nd, 4th, tritone, or 7th between the two voices.

- Parallel 5ths and 8ths are forbidden. This is a general rule for all counterpoint and part-writing.

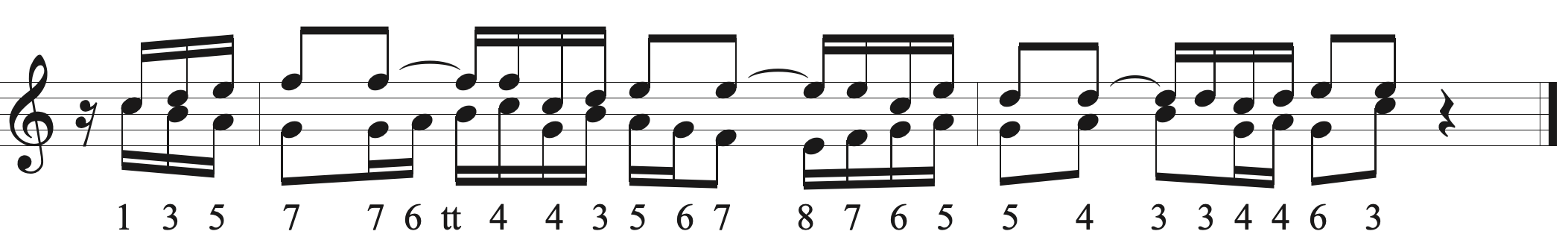

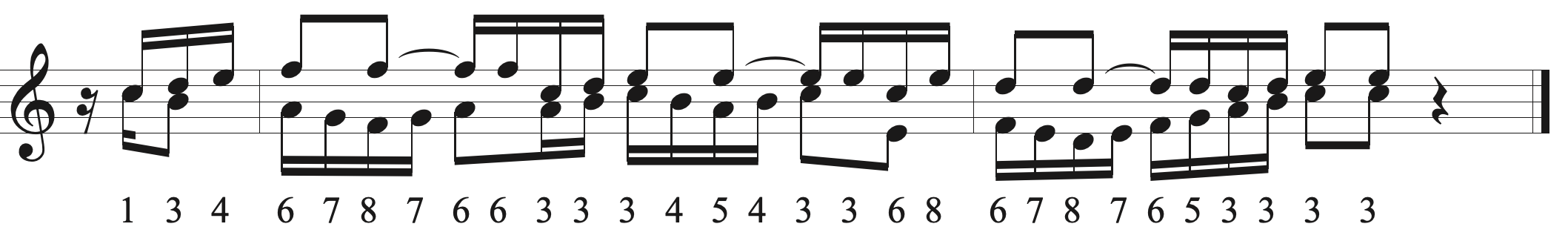

Example (write the intervals for each vertical pair of notes below the staff and find three errors):