10.4 Part Writing, Second Inversion Triads: Tutorial

Part Writing with Triads in Second Inversion

Second inversion triads were originally considered a dissonant sound that resulted from adding non-chord tones between chords. They had a perfect 4th interval between the bass and an upper voice, which is an interval that was originally considered a dissonance. Though we now consider second inversion triads to be chords, their function is still to embellish the chords around them. Chord inversions become more unstable the farther away they are from root position. Second inversion triads are less stable than first inversion or root position chords, and create more motion because they need to move to another chord. Second inversion chords are used much less frequently than root position or first inversion triads, and because they function as embellishing chords, they are not used as substitutes for root position or first inversion triads. Four types of second inversion triads are used in music. When part writing, a second inversion chord must be one of these four types in order to be used in a progression.

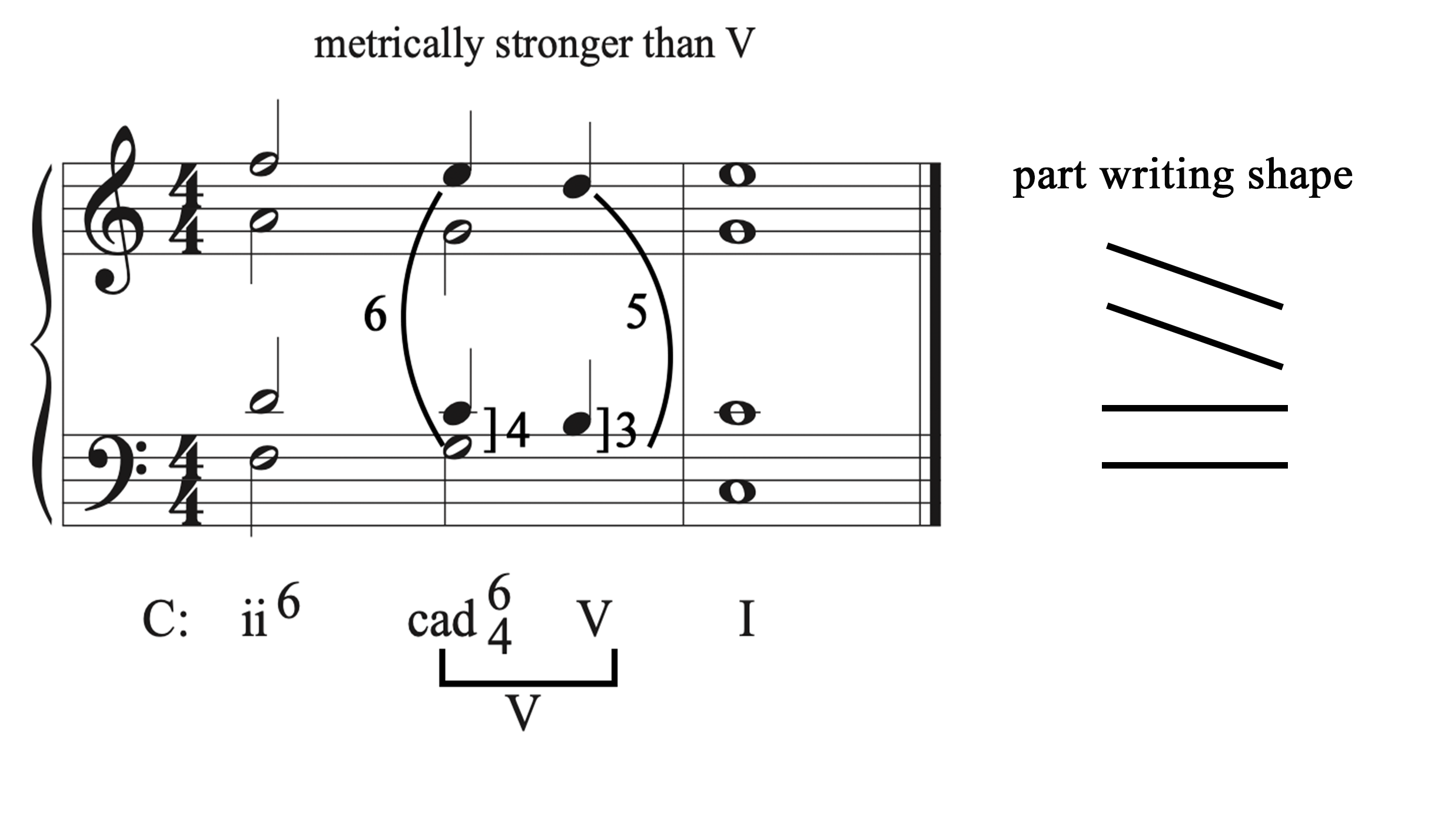

Cadential 6/4 chord

The cadential 6/4 chord is the most common 6/4 chord used in music. It is spelled as a I 6/4 chord, but serves to decorate a V chord, directly preceding it at a cadence. Since it is functioning as a decoration to the V chord, it is assigned a dominant function, not a tonic function. A cadential 6/4 chord must meet the following criteria when used during part writing:

- It must be metrically stronger than the V chord that comes after it.

- One of the upper voices will double the bass and serve as common tones between the cad 6/4 and V chords.

- The other two upper voices will move down by step, using intervals 6-5 and 4-3 above the bass.

- Make sure to label the cad 6/4 properly. The I 6/4 chord is labeled as cad 6/4. The V chord that follows it is bracketed together with the cad 6/4 chord, and we write V underneath both chords to show that both chords together are considered a V chord with embellishment. Note that while this label is commonly used for cadential 6/4 chords, other ways to label a cadential 6/4 chord exist.

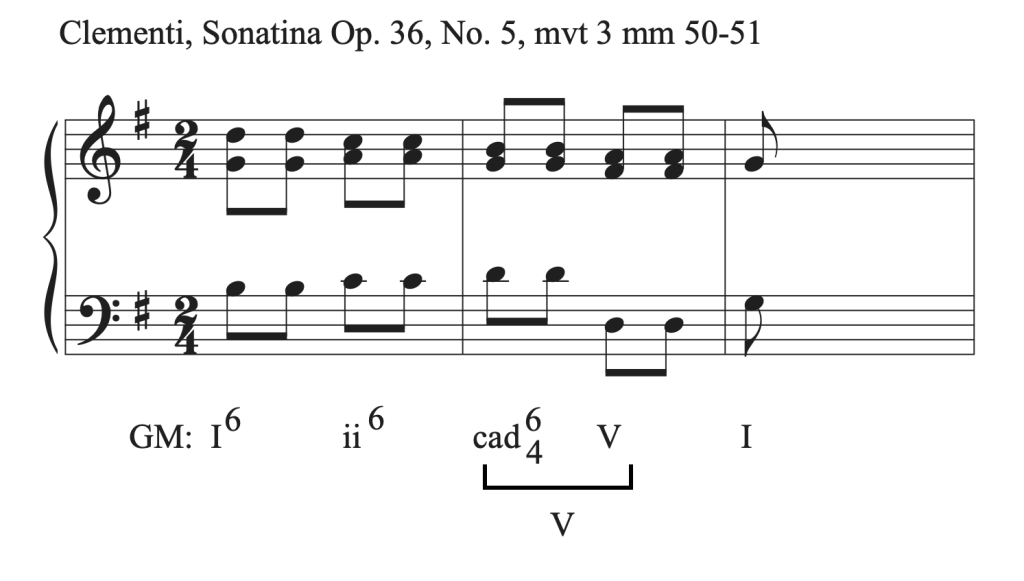

Here’s an example of a cadential 6/4 chord in music:

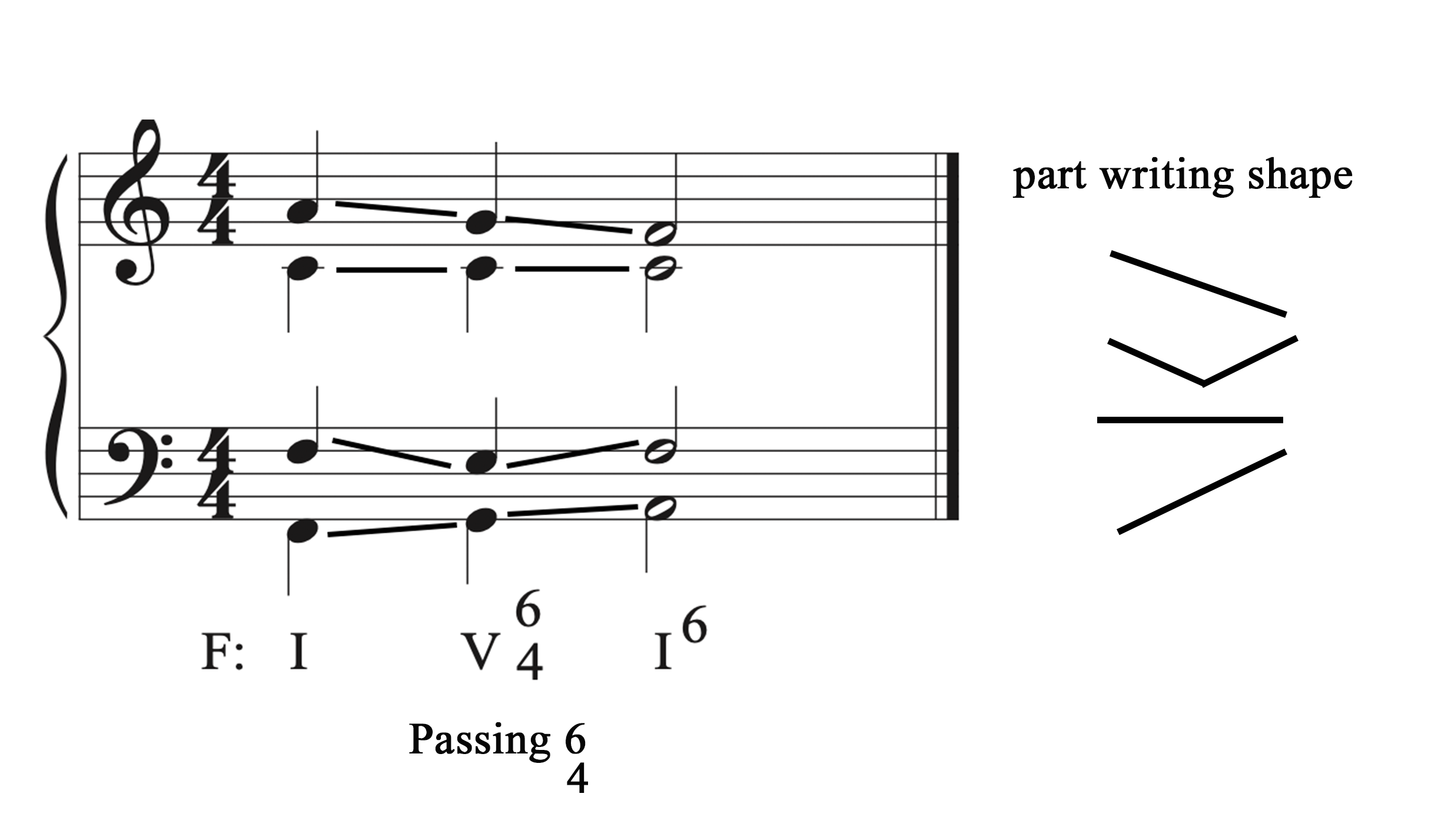

Passing 6/4 chord

Another type of 6/4 chord is called the passing 6/4 chord due to how the chord passes between the chords that surround it. The passing 6/4 chord is often used to connect the following chords:

- As a V6/4 chord between two I chords

- As a I 6/4 chord between two IV chords

- It is usually metrically weaker than the chords that it embellishes.

Part writing a passing 6/4 uses the following motion:

- The bass steps up between the two surround chords, or steps down between the two surrounding chords.

- One of the upper voices will step in the opposite direction as the bass.

- One of the upper voices is a common tone between all three chords.

- One of the upper voices will act as a lower neighbor between the two surrounding chords.

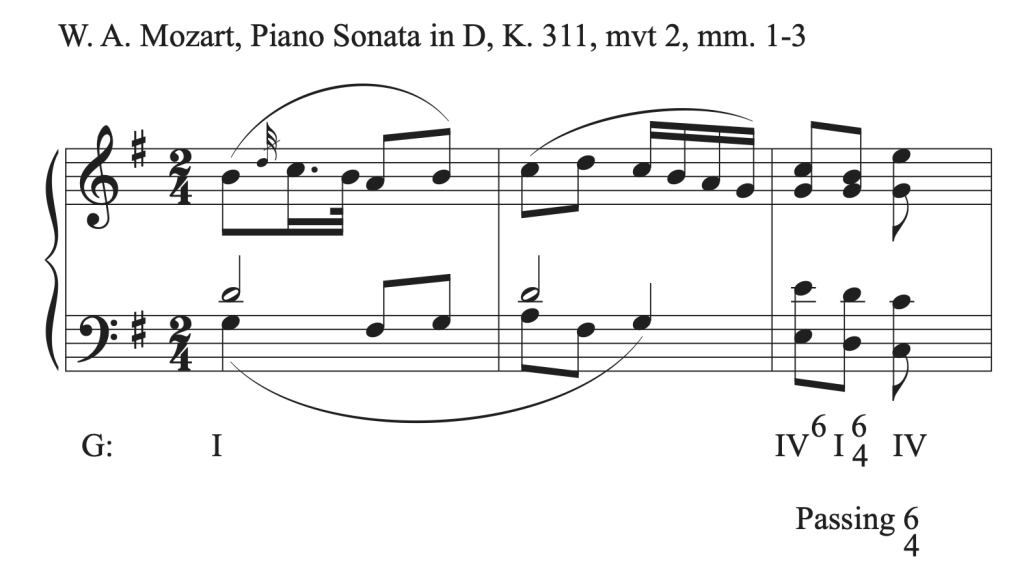

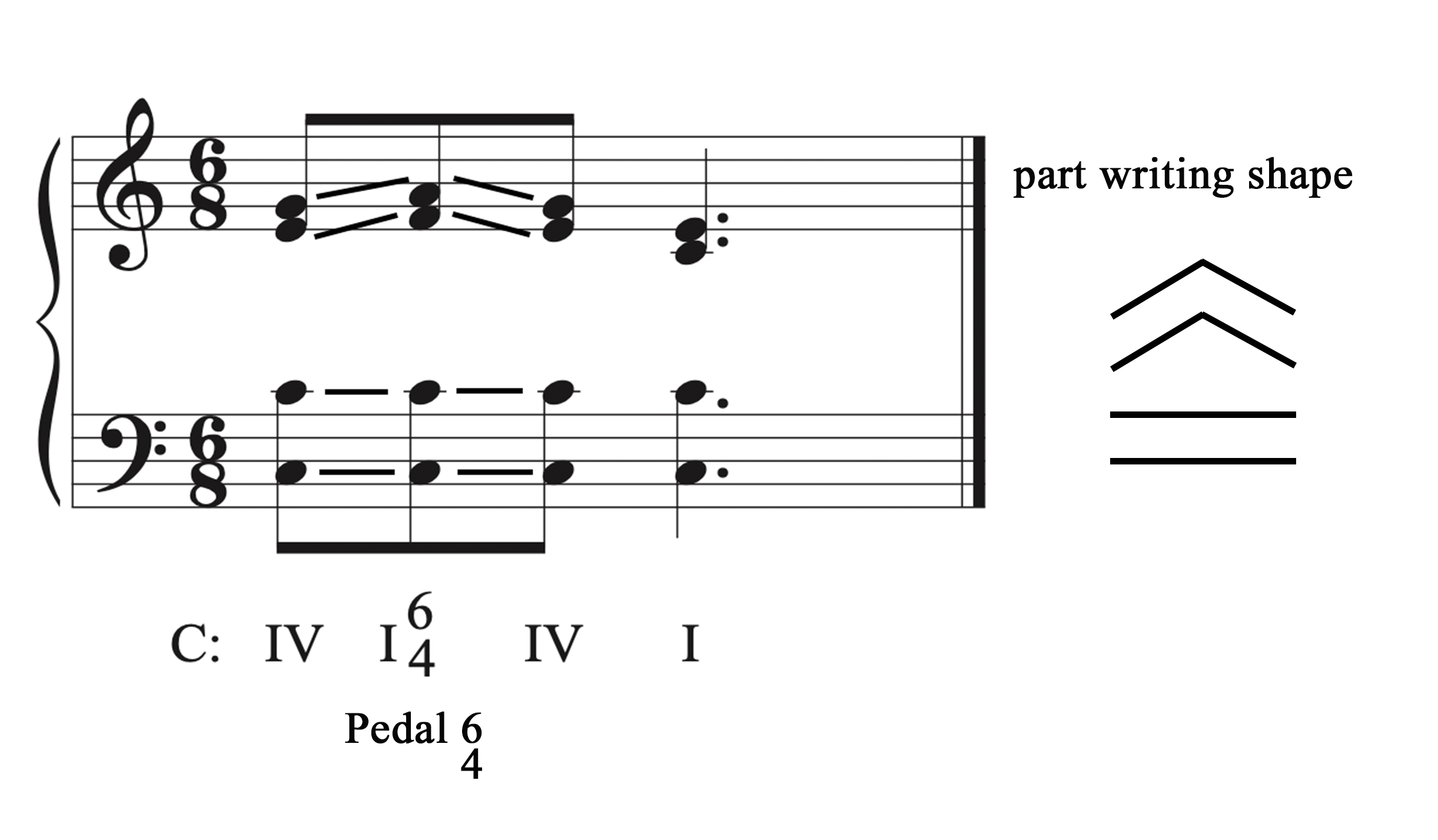

Here’s an example of a passing 6/4 chord in music:

Pedal 6/4 chord

The pedal 6/4 chord is also called a neighbor 6/4, embellishing 6/4, or static 6/4. These names derive from the way it moves to connect chords. Pedal 6/4 chords often connect the following two chords:

- As a I6/4 chord between two V chords

- As a IV 6/4 chord between two I chords

- It is usually metrically weaker than the chords it embellishes.

Part writing a pedal 6/4 uses the following motion:

- The bass is sustained as a common tone between all three chords.

- One of the upper voices is also sustained as a common tone between all three chords.

- Both of the other upper voices create upper neighbors with the surrounding chords.

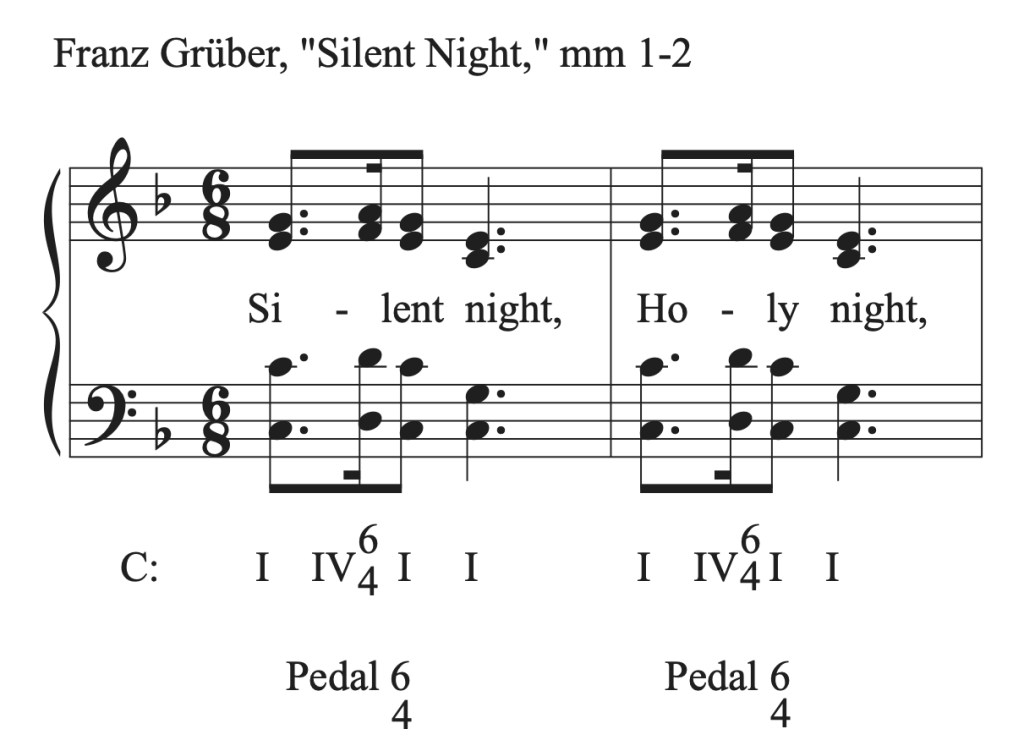

Here’s an example of a pedal 6/4 chord in music:

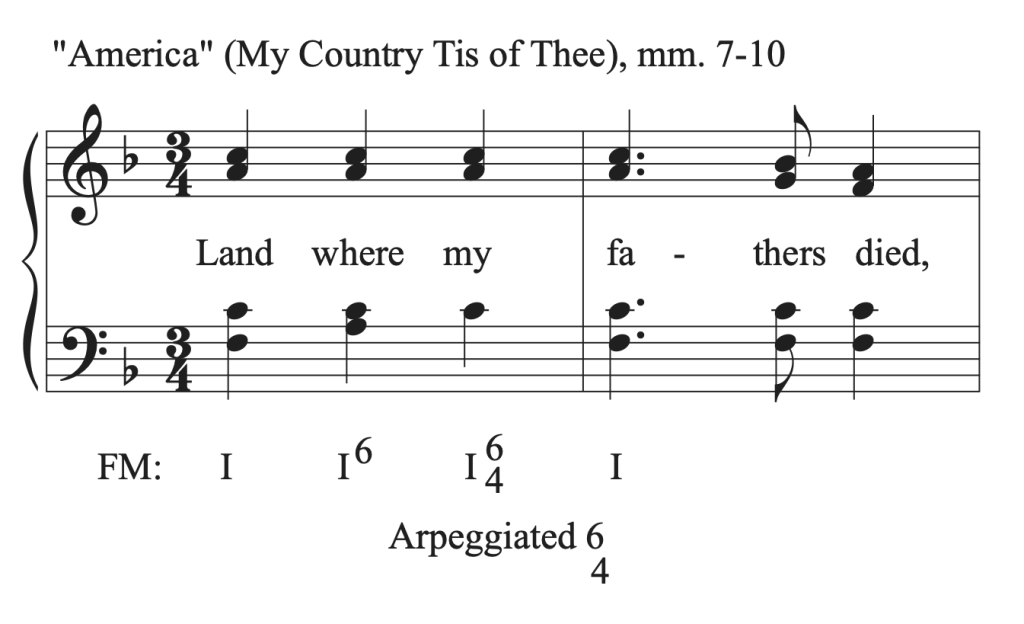

Arpeggiated 6/4 chord

The arpeggiated 6/4 chord results from a bass arpeggiation. Most often, either tonic or dominant is arpeggiated. An arpeggiated 6/4 chord is usually metrically weak, but can appear in either position. Since the same harmony is used between the root position or first inversion chord and the arpeggiated 6/4 version of the chord, it does not have specific part writing motion for each voice like the other second inversion chords. Here’s an example of an arpeggiated chord in music:

Summary of Part Writing with Second Inversion Chords

- The bass voice will be doubled in all second inversion triads.

- You must follow the part writing guidelines specific to each chord.

- Cadential 6/4

- Metrically stronger than the V chord that comes after it

- Bass and an upper voice doubled with a common tone

- Remaining upper voices move to create 6-5 and 4-3 intervals above the bass

- Label the cadential 6/4 correctly to show its dominant function

- Passing 6/4

- Bass moves by step

- One upper voice moves by step in contrary motion to the bass

- One upper voice holds a common tone

- One upper voice uses a lower neighbor motion

- Pedal 6/4

- Bass sustained over all three chords

- One upper voice doubles the bass in all three chords

- Remaining upper voices move in upper neighbor motion

- Arpeggiated 6/4

- Used as an arpeggiation of the same chord

- Cadential 6/4

Proceed to the theory exercises for guided examples for part writing with second inversion chords.