6.2 Cadences: Tutorial

Cadences

Cadences are like punctuation marks in music. They are harmonic events that serve to separate phrases to some degree. In order to learn more about cadences, it is important to have a basic knowledge of phrases in music.

Phrase

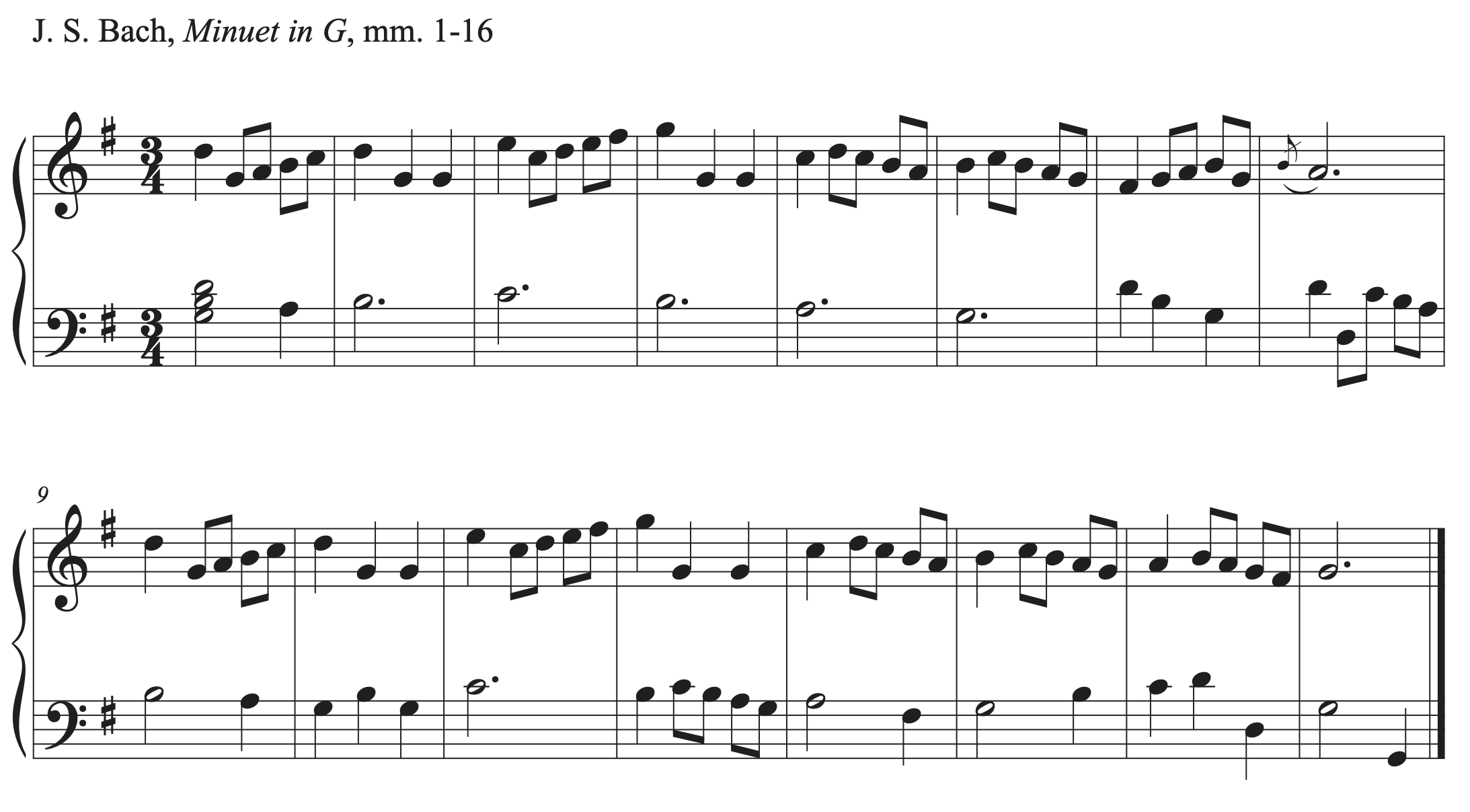

A phase is a basic unit of musical thought, similar to a sentence in language. Phrases end with punctuation marks in the form of cadences. A common phrase length is four bars, though phrases can be longer or shorter. Phrases are often combined into larger groups or divided into subphrases. The essential component of a phrase is a cadence, or degree of separation. Listen to the following example to hear where the punctuation marks occur.

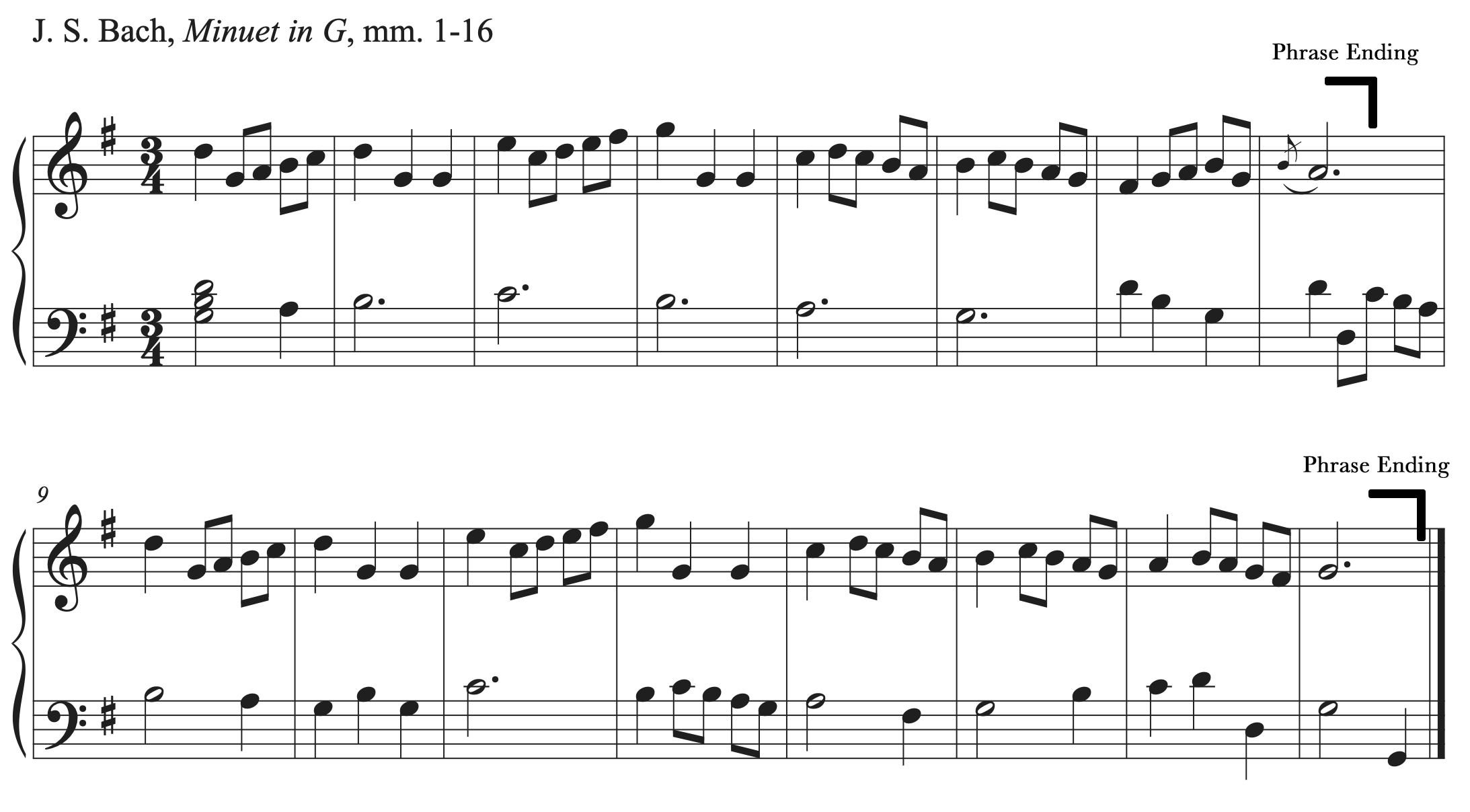

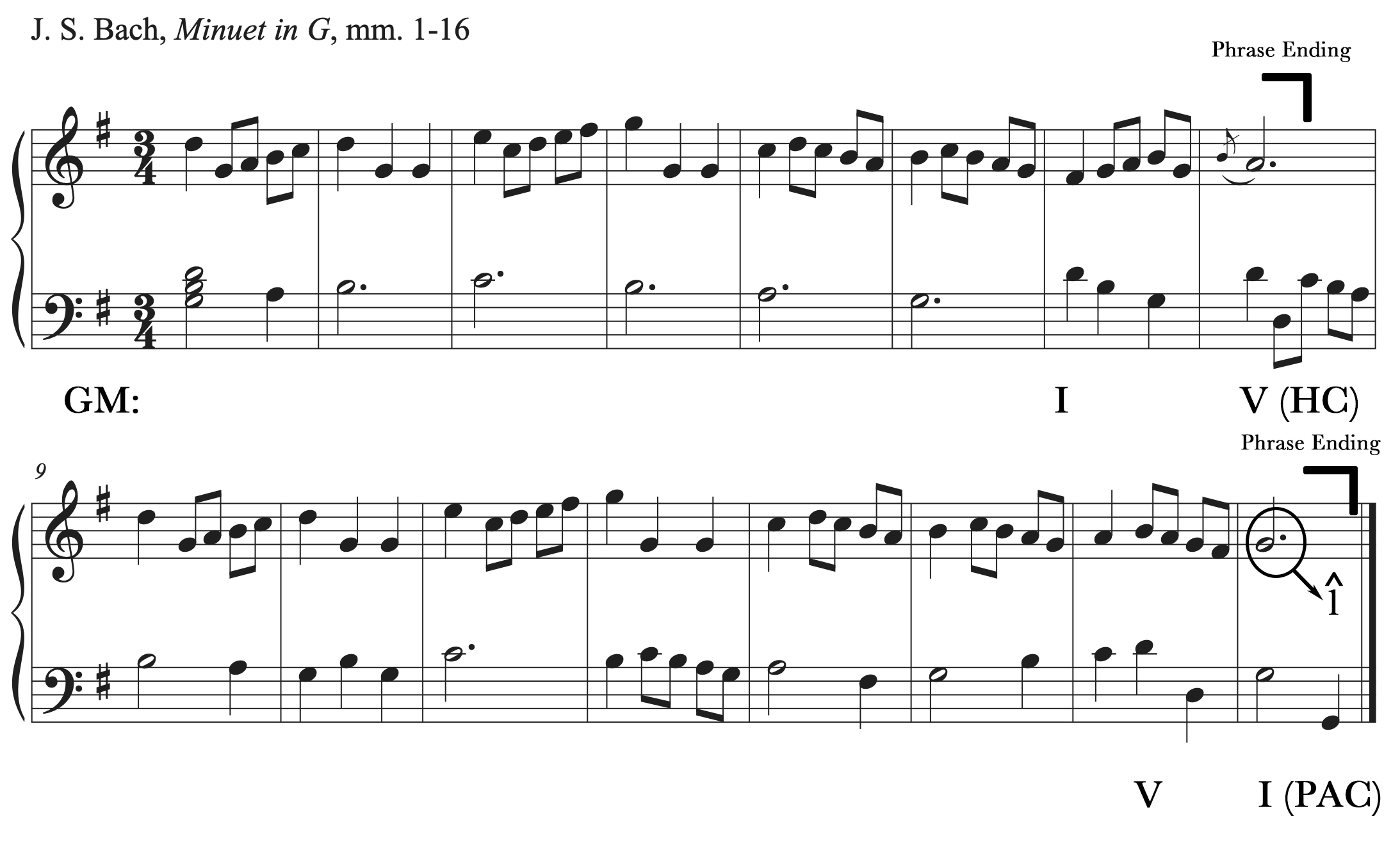

We mark phrase ending with half brackets to show separation. Look at the score below to see the phrase markings. Then, listen to the recording again to hear the cadences that occur at the ends of both phrases. Does the first cadence sound conclusive, like a period? Or does it sound like the music must continue? Does the final cadence sound more or less conclusive than the first?

Cadences are points of rest and separation in the music. They can group, separate and dramatize musical ideas. They can be the equivalent of a comma, a period, or even an exclamation point.

Cadences have different degrees of finality and strength. Some are final and can end motion completely (called conclusive cadences), and some require that the music continues after a pause (called progressive cadences). The type and strength of a cadence is dependent on harmony and chord inversion, melodic motion, and metric placement. A cadence that is on a stronger beat will be stronger than a cadence on a weaker beat. Composers can choose the placement of a cadence and the chords and melody used in order to vary the strength of cadences and their relationships to one another in the piece.

Cadence Types

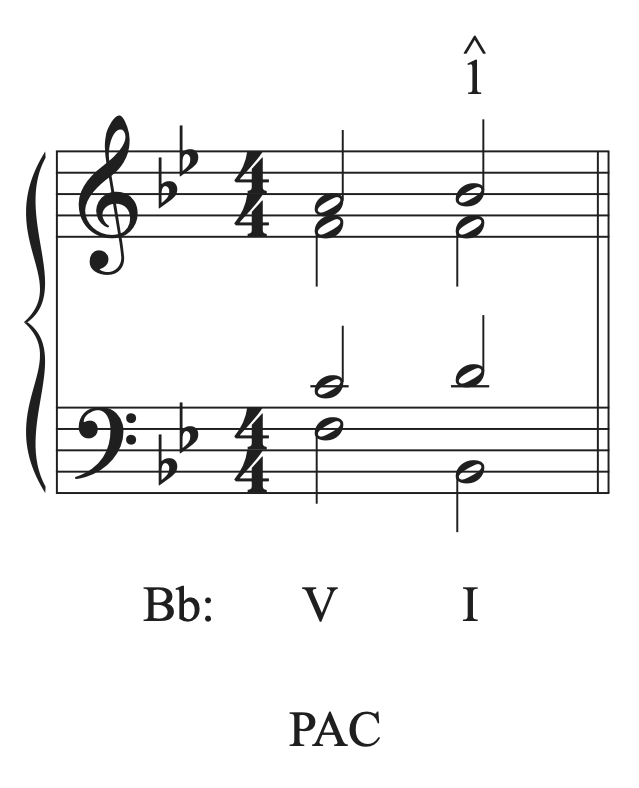

Perfect Authentic Cadence (PAC)

- The strongest, most conclusive type of cadence. Good for the last cadence of a piece.

- Chords: V-I (or V7-I) in major or minor

- In order to be a PAC, two things must be true:

- Both chords must be in root position

- The melody must end on scale degree 1

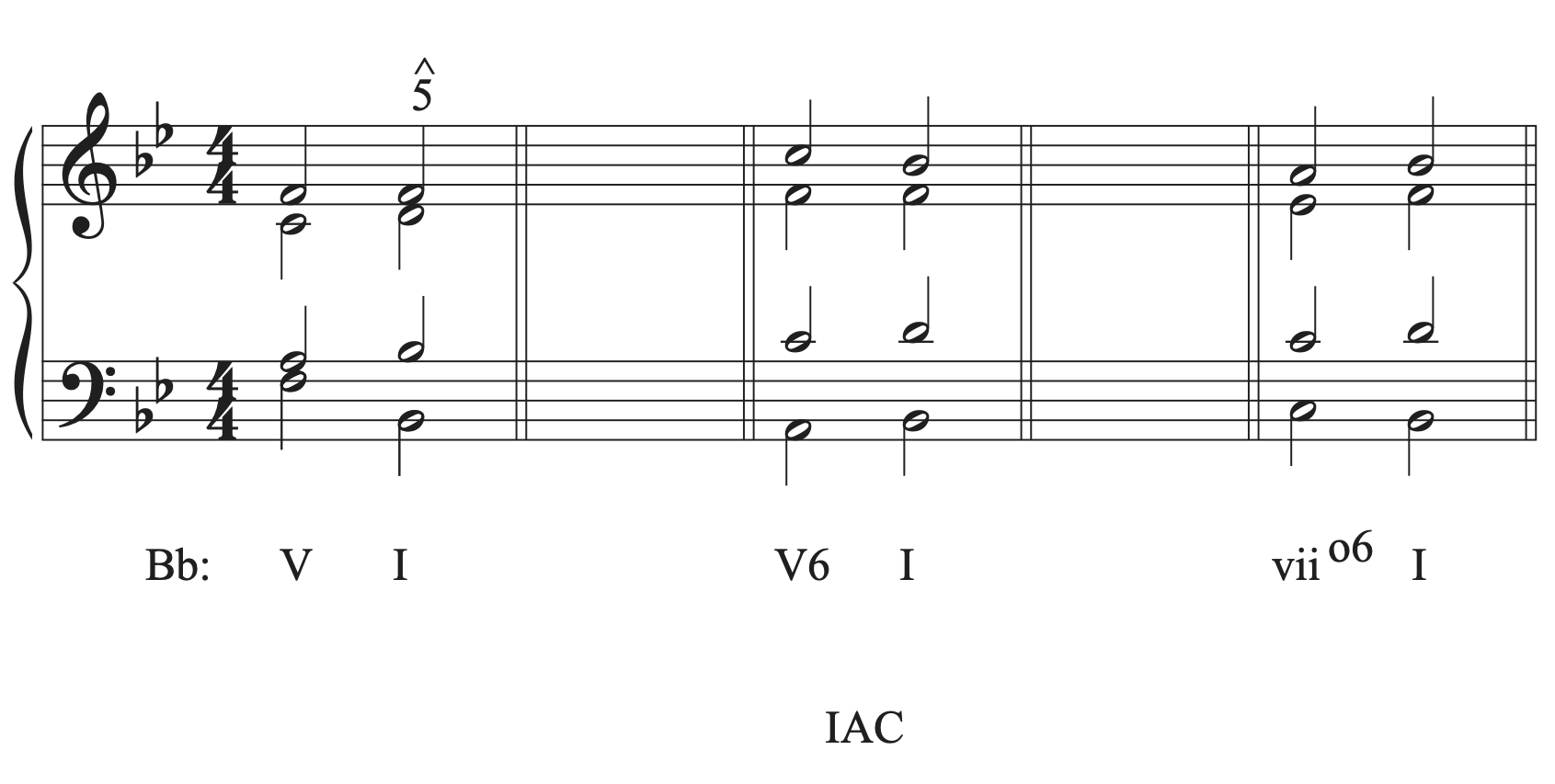

Imperfect Authentic Cadence (IAC)

- A conclusive cadence, but not as strong as the PAC. It is often used for cadences on a tonic harmony that occur in the beginning or middle of a piece.

- Chords: dominant to tonic.

- Triads can be in root position or first inversion.

- Seventh chords can be in any inversion.

- Melody can end on scale degree 1, 3, or 5

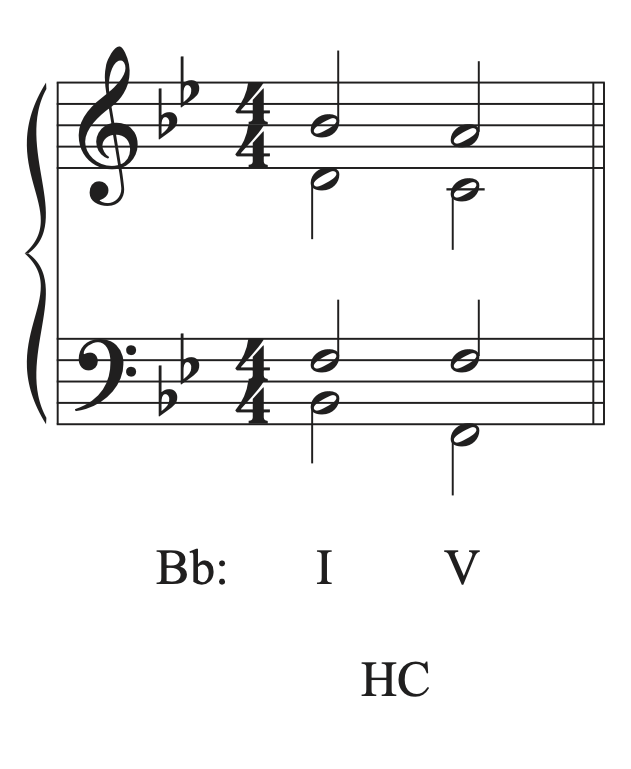

Half Cadence (HC)

- Progressive cadence. The music must go on after a HC.

- Harmony ends on a V chord (preceding chord can be any other chord)

- Technically, the last chord can be any chord except I, but it most often ends on V

- No specific melodic motion requirement

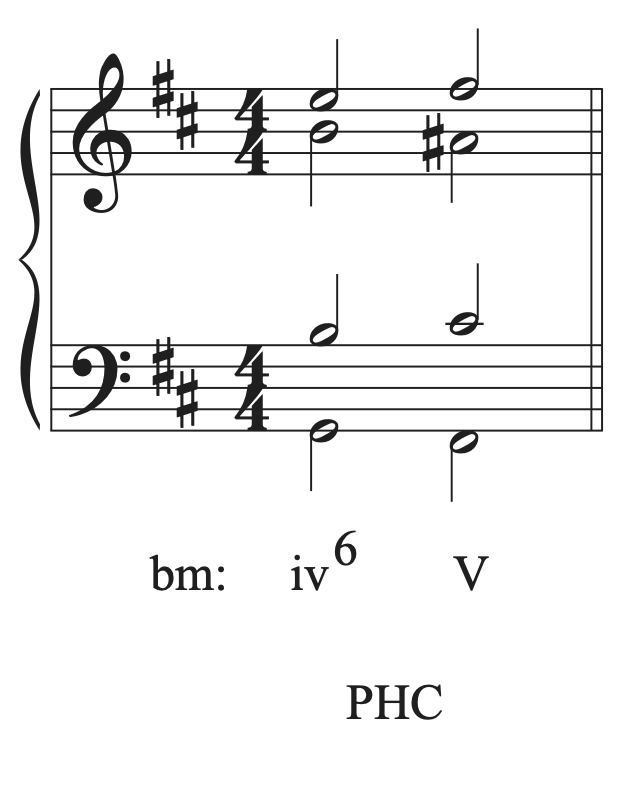

Phrygian half cadence (PHC)

- Progressive cadence. It’s a special type of half cadence named for the descending half step motion in the bass.

- Chords: iv6-V in minor keys only

- No specific melodic motion requirement

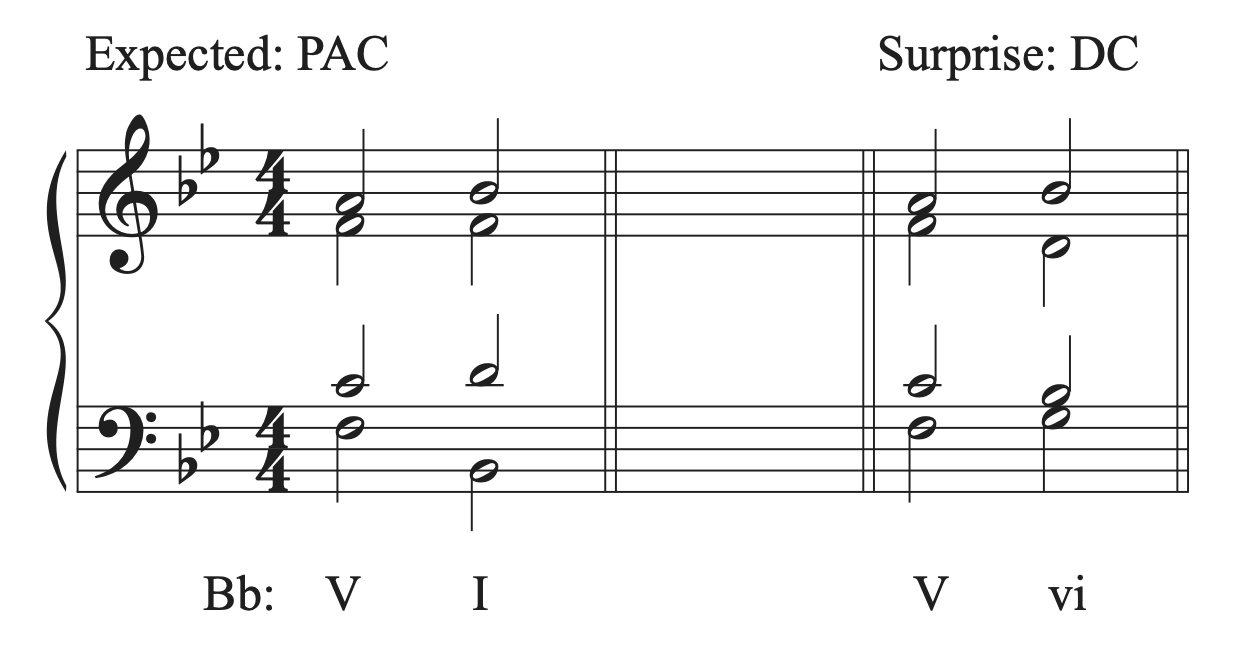

Deceptive Cadence (DC)

- A progressive cadence:

- A surprise ending! Results when the ear expects a V-I authentic cadence but gets V-vi chord instead.

- Often used to extend a phrase a few bars until reaching a true authentic cadence.

- No specific melodic motion requirement

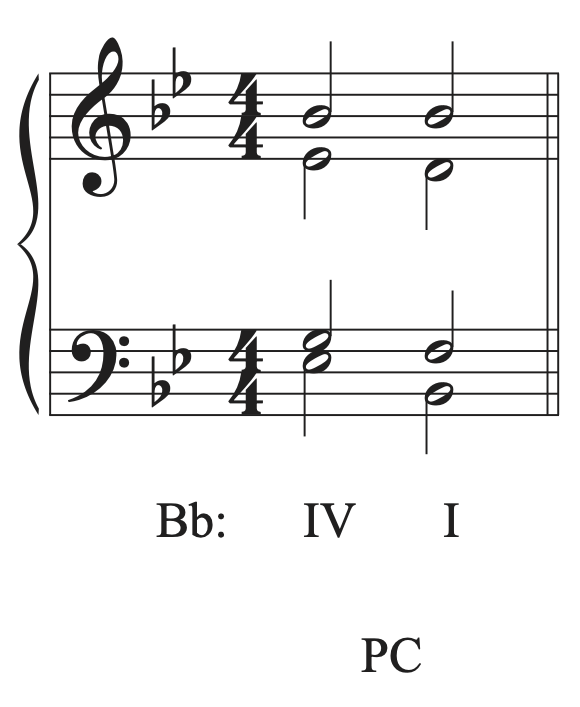

Plagal Cadence (PC)

- A type of authentic cadence, though not as strong as the PAC or IAC (since it has no leading tone)

- Often called the ‘Amen’ cadence because of its use for the final chords in hymns.

- Occurs less often than the PAC and IAC

- More commonly used in gospel and blues than in classical music

- Chords: IV-I

- No specific melodic motion requirement

Important Note: a harmonic progression can include any of the progressions (chords) found at a cadence. This does not automatically make it a cadence point. A cadence is the goal of a phrase, which has some degree of rest and separation.

Let’s return to the Bach example to look at the cadences that were used and how they relate to one another.

Notice that the first cadence is a half cadence (HC). That’s why it sounds like the music cannot end at the end of that phrase. Compared the final cadence, which is a perfect authentic cadence (PAC), is much stronger than the half cadence. While the half cadence is a great choice to use to separate the phrases in the middle of the piece while creating motion, the perfect authentic cadence, as the strongest cadence possible, is the best choice to end the section. Notice that the tonic chord in the PAC ends on beat 1, the strongest beat possible, which makes the cadence even stronger.

Listen and look for phrases and cadences in the music you are currently playing or studying. Can you hear different types of punctuation in music? How do the cadences progress from the beginning to the ends of sections and through full pieces? Where are the weaker cadences located? Where is the strongest cadence located and what makes it stronger than the ones around it? Can you hear the different between the different types of cadences? Listen to music without the score to see if you have the same ability to hear phrases and cadence types without written notes to visually analyze.