7.2 Melodic Material: Create/Vary/Repeat and Sequences: Tutorial

Melodic Variation and Repetition

The options available to a composer writing melodic material include: create a new idea, vary the idea, or repeat the idea. New material is melodic material that has not yet been seen in the music. A variation takes the original material and changes aspects of it. It could have decorative notes, or changes in rhythm and contour, for example. A variation sounds and looks similar to the original material, but is not exactly the same. A repetition of the melodic material takes the original material and either repeats it so that it is exactly the same, or repeats it so that it is primarily the same but is transposed so that it starts on a different pitch.

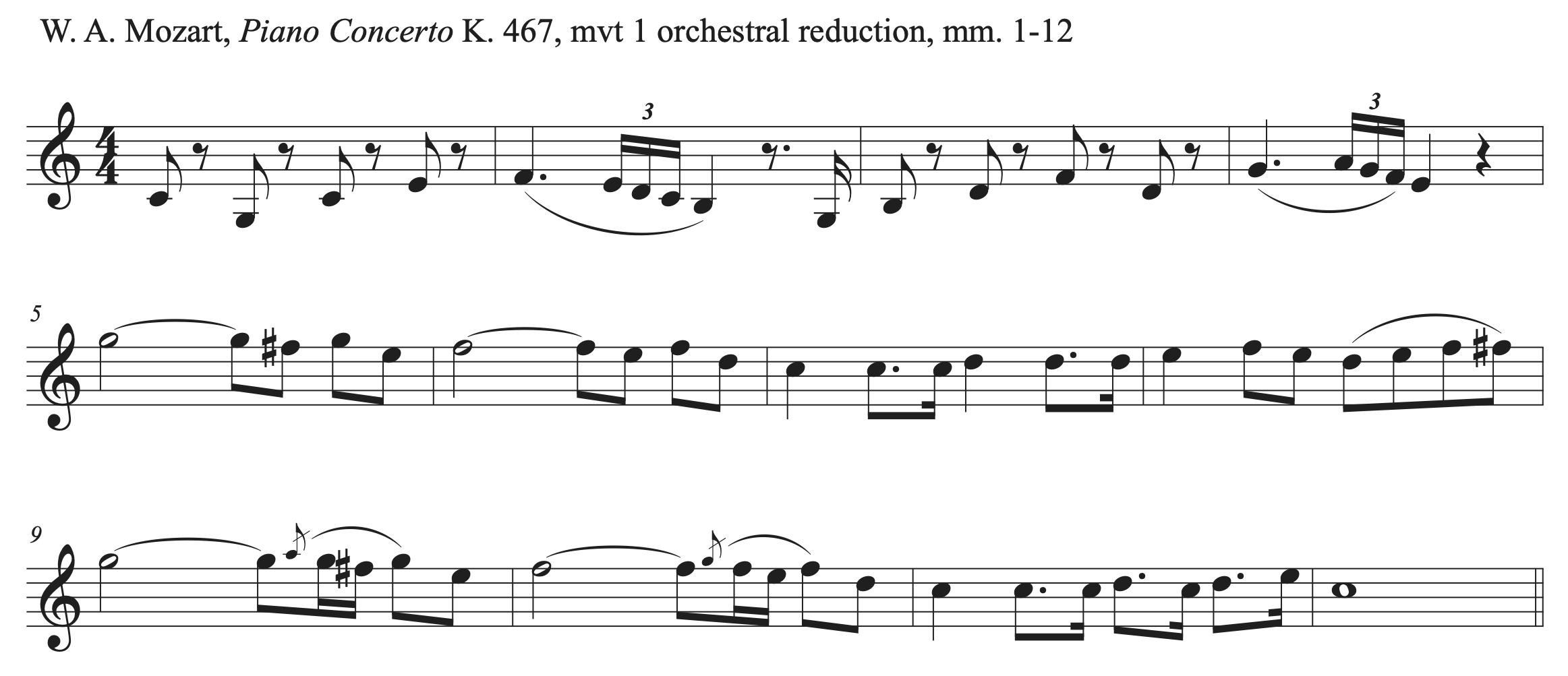

Let’s look at an example and listen to the recording to see how these three options are used in the example below.

The first notes of the composition are considered new material because nothing else has happened yet to compare them to. New material continues until a variation or repetition is seen. In b. 3 of the example above, we see material that looks very similar to the opening two bars. It is not exactly the same, so it is not a direct repetition. It is also not the same material repeated at a different pitch level. It has changes in the shape of the line (contour). Instead of descending for the first interval, it ascends. We see several changes to contour. The material in b. 3 also includes a pickup note that was not part of the original material. Because it includes these changes, but is still recognizably related to the music of the first two bars, we call bars 3-4 a variation. Bar 5 begins with material that we haven’t yet seen, so is labeled N for new material. Bar 6 repeats bar 5 starting on a different pitch level, so is labeled as a repetition (R). Bar 7 consists of new material (N). Bar 9 looks a lot like bar 5, but is decorated with a grace note and has a different rhythm. We call that a variation of bar 5 (V). Bar 6 looks like a repetition of bar 9 at a different pitch level. It is also a variation on the music in bar 6. So, we indicate both relationships in the score. Bar 11 looks like the material in b. 7, but with variation in rhythm and contour, so it called a variation (V). Look at the example below and listen to the recording again to see if you can hear the differences between creating new material, varying the material, and repeating the material.

Repetition in Music

Music relies heavily on repetition. In fact, repetition is a vital feature in music of all genres. To understand how music repetition affect us, watch this video:

Understanding repetition can help you:

- Sight read better

- Practice more efficiently

- Understand how musical ideas develop—help you create a musical interpretation

- Know what connects the repeated ideas

- Know how the repeated ideas move forward

- Know how the repeated ideas connect

Motives

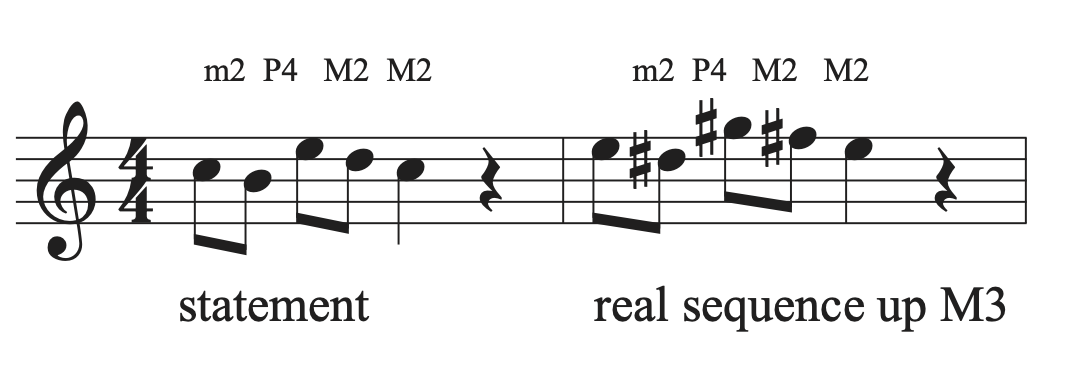

Repetition in music can be exact or modified. It can apply to small musical units or large units. Motives in music are short figures that are used as building blocks to generate compositional material. One of the most famous examples of the successful use of a motive is Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5.

Beethoven’s famous motive consists of a pitch element: two notes that are a Major 3rd apart, and a rhythmic element: three eighth notes leading to a half note. Beethoven uses both elements separately as well as together to generate an entire symphony’s worth of music. Listen to the symphony and see if you can catch the many ways that Beethoven uses the motive.

Beethoven video with score:

Link to score on imslp.org (scroll down to find public domain score): Symphony No.5 in C Op.67 (Beethoven,_Ludwig_van)

Sequence

A melodic sequence is a melodic idea that is immediately repeated at a different pitch level. We label sequences by their type as well as their interval of transposition. There are two types of melodic sequences: real and tonal.

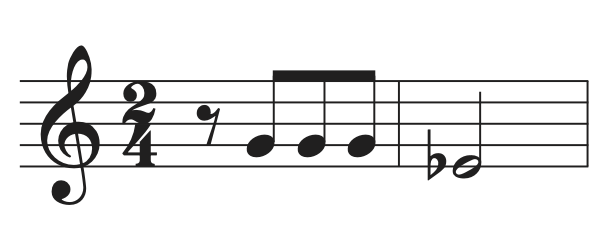

A real sequence uses the exact intervals between each pitch as the original melody statement.

In the example above, the intervals are exactly the same between statement and sequence, so it is a real sequence. To name the level of transposition, look at the first note of the statement in comparison to the first note of the sequence. The sequence starts a Major 3rd higher. The full label for the sequence is: real sequence up M3.

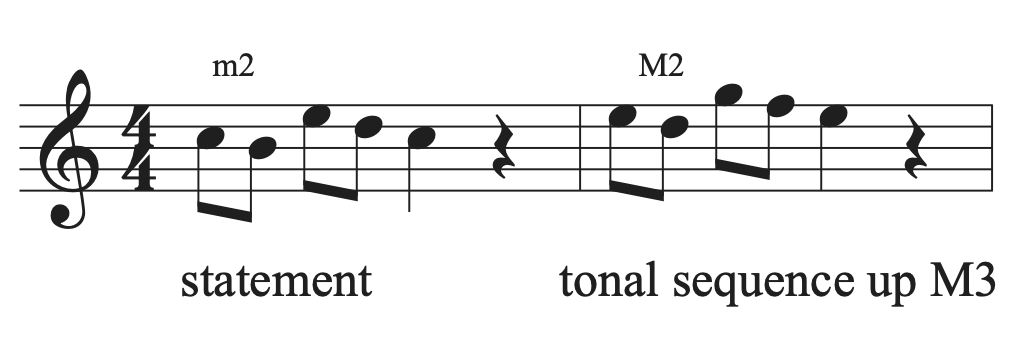

A tonal sequence alters the quality of the intervals in order to remain in the same key.

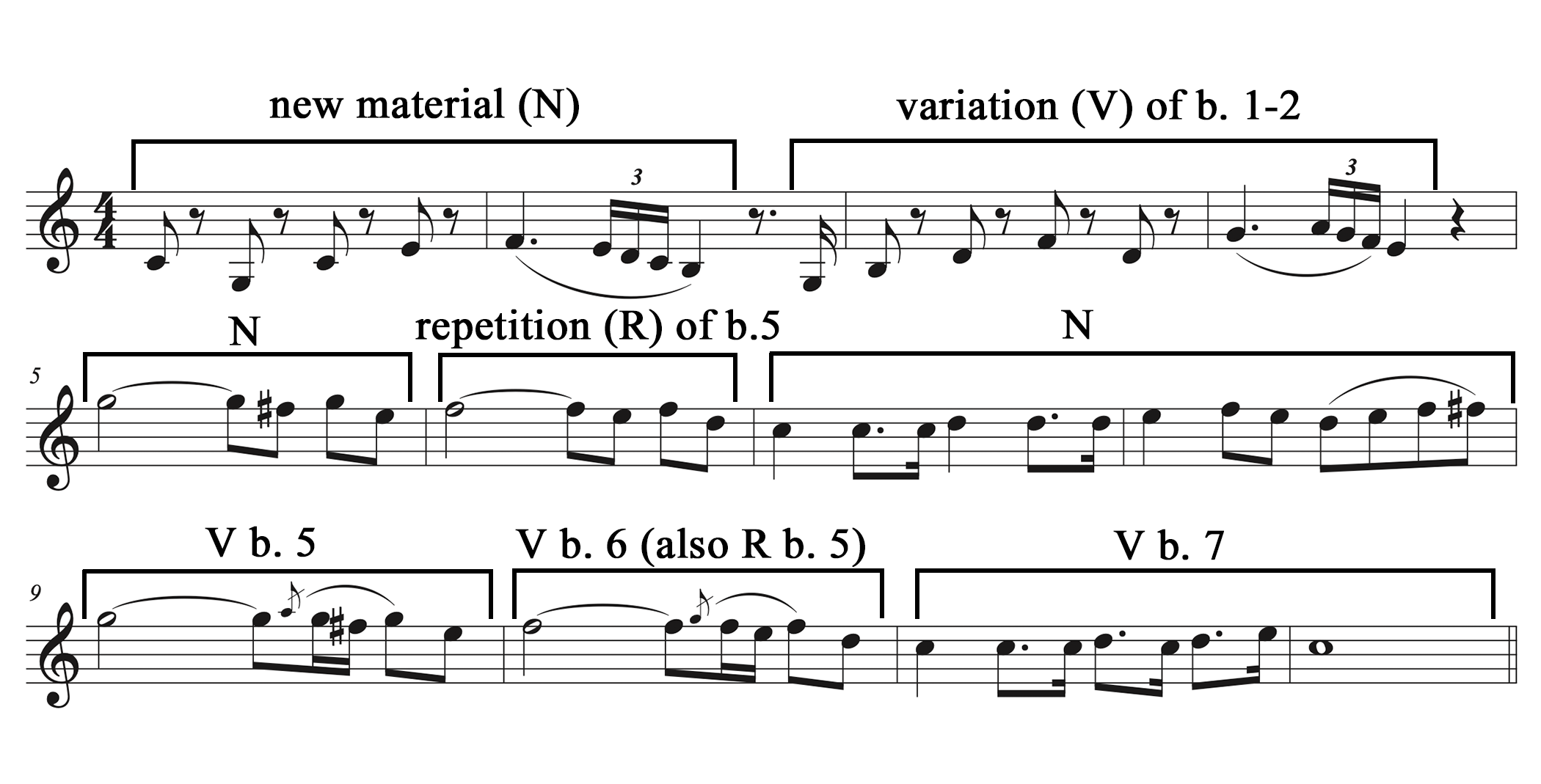

In the example above, the first interval in the sequence was changed in order to stay in the key (not use accidentals outside of the key). Therefore, the sequence is tonal. The first note of the sequence is a M3 higher than the first note of the statement, so the full label for the sequence is: tonal sequence up M3.

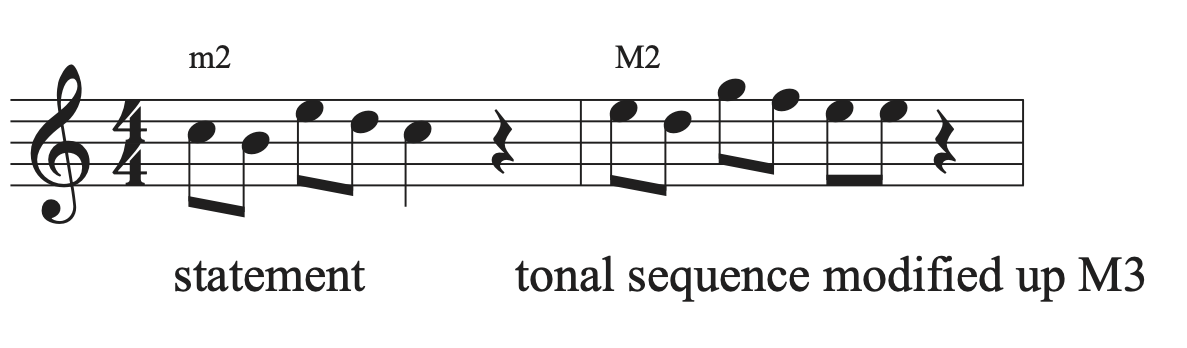

Both real and tonal sequences can be modified by changing the rhythm or contour.

In the example above, the rhythm in the last beat of the sequence was altered. So, the full label for this sequence is: tonal sequence modified up M3.

Labeling sequences in music

- Identify the statement: The first step to labeling sequences is finding where the statement (original melody) ends and when the sequence begins. The beginning of the sequence will look exactly like the beginning of the original melody written at a different pitch level. A sequence starts immediately after the statement ends, so there should be no extra music between the end of the statement and the beginning of the sequence. Once you have found the end of the statement, bracket it and label it “statement”.

- Determine the type of sequence: compare each interval in the statement with each interval in the sequence. If all intervals are exactly the same, it is a real sequence. If the interval size is the same, but the quality was altered (in order to stay in the same key), it is a tonal sequence. If any part of the rhythm or contour was changed, include the word “modified” after either “real” or “tonal” in your label.

- Determine the level of transposition of the sequence: look at the first note of the statement compared to the first note of the sequence. Make sure to include the exact interval and direction used between the two notes. For example: up a P4.

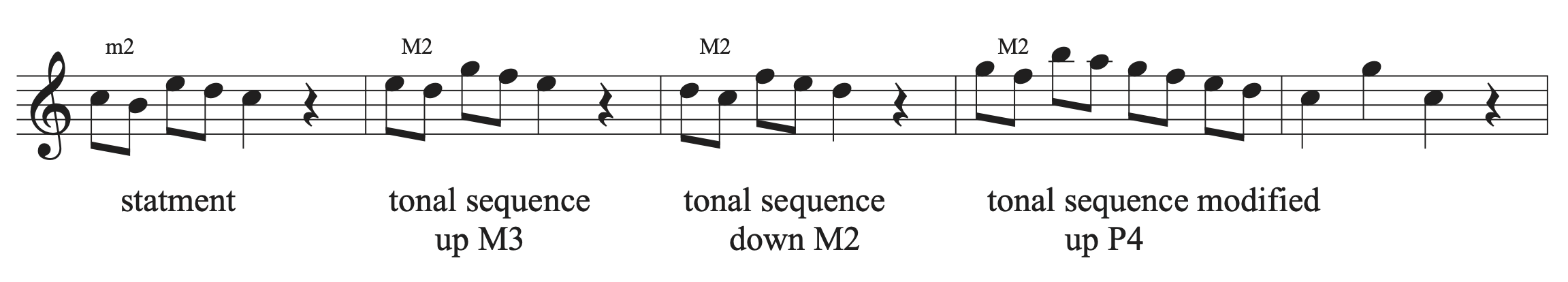

- Follow these steps to identify each reiteration of the sequence. Level of transposition is measured from the first note of the statement to the first note of the first sequence. If there are more sequence reiterations, the level of transposition of the second sequence repetition is measured from the first interval of the first sequence repetition to the first interval of the second sequence repetition, etc. The type of sequence is always compared to the statement. It is possible to have different types of sequences used in different repetitions of the sequence, so make sure to check each one.

Sequences usually are repeated 3 times before moving on to different material. This is often called the “rule of 3.” Repeating the sequence 3 times limits predictability and keeps interest going. Note that the example below uses the rule of 3.

Sequences are common ways to create repetition in music. Can you find any instances of sequences in the music you are currently practicing or studying? If so, identify the type and think about why the composer chose either a real or tonal sequence. How would substituting a different type of sequence change the sound of the music?

Sequences are prevalent in classical music, but are just as popular in other genres. Watch this video to learn more about sequences in pop music: Songs that use sequence